- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

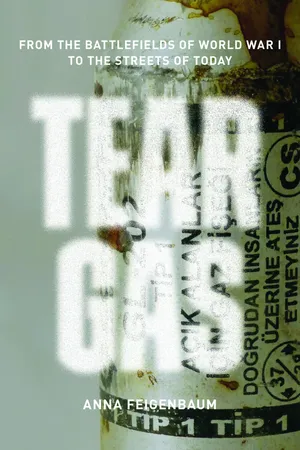

About this book

One hundred years ago, French troops fired tear gas grenades into German trenches. Designed to force people out from behind barricades and trenches, tear gas causes burning of the eyes and skin, tearing, and gagging. Chemical weapons are now banned from war zones. But today, tear gas has become the most commonly used form of "less-lethal" police force. In 2011, the year that protests exploded from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street, tear gas sales tripled. Most tear gas is produced in the United States, and many images of protestors in Tahrir Square showed tear gas canisters with "Made in USA" printed on them, while Britain continues to sell tear gas to countries on its own human-rights blacklist.

An engrossing century-spanning narrative, Tear Gas is the first history of this weapon, and takes us from military labs and chemical weapons expos to union assemblies and protest camps, drawing on declassified reports and witness testimonies to show how policing with poison came to be.

An engrossing century-spanning narrative, Tear Gas is the first history of this weapon, and takes us from military labs and chemical weapons expos to union assemblies and protest camps, drawing on declassified reports and witness testimonies to show how policing with poison came to be.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tear Gas by Anna Feigenbaum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Chemical Warfare in World War I

The industrial revolution heralded advances in science and healthcare. It gave rise to a radical optimism in political thought but at the same time created a new intensity of human exploitation. With the arrival of vaccines, there also came workhouses. Alongside more civilized technological advances, the nineteenth century witnessed a marked increase in the sophistication of weaponry. It was the century of the first modern wars—where rifles replaced muskets and ironclads took over from wooden warships. Early chemical weapons had been used in ancient societies around the world, but in the mid-1800s the rise of modern chemistry brought more complex ethical discussions surrounding chemical weapons and their use in warfare.1

Advocates of chemical weapons, eager to make use of new scientific discoveries, put forward their case that gas was as honorable a way to kill as a sword or cannon. During the Crimean War a well-respected British chemist, Sir Lyon Playfair, proposed using cyanide shells against the Russians. When the War Office rejected this proposition on ethical grounds, Sir Playfair’s response foreshadowed the position of military chemists of the early twentieth century:

There’s no sense to this objection. It is considered a legitimate mode of warfare to fill shells with molten metal which scatters upon the enemy and produces the most frightful modes of death. Why a poisonous vapor, which would kill men without suffering, is to be considered illegitimate is incomprehensible to me. However, no doubt in time chemistry will be used to lessen the sufferings of combatants.2

Proposals to use chemical warfare were also presented and rejected during the US Civil War. Writing to Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of war, a New York schoolteacher, John W. Doughty, proposed the use of chlorine shells, arguing that although these weapons had horrid effects, their use could bring about a faster resolution to the conflict. Early efforts to ban the use of chemical weapons in warfare were brought to the table at the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. Delegates sought to put in place some restrictions on the use of biological and chemical weapons. However, these agreements were bound together by ambiguous phrases and offered few practical guidelines for enforcement. The ambiguity of these international agreements would come to the forefront, as poison gas filled the trenches and the international media stage during World War I.

Gas in the Trenches

Nestled into trench dugouts on both sides, soldiers couldn’t fire on opposing troops; trenches were at once protective hideaways and traps. The close proximity of each side’s trenches to each other caused artillery shells to backfire, injuring one’s own men. Trench warfare was often an endless stalemate, as neither side could advance enough to end the war.

While the “who hit who first” debate remains open for historical interpretation, it is generally held that French troops fired tear gas grenades, filled with methylbenzyl bromide, into German trenches in August of 1914.3 While the exact details of this first tear gas launch are fuzzy, leading historians mark the Battle of the Frontiers as World War I’s first deployment of modern tear gas. A much larger and more lethal attack by the Germans followed in 1915, with the first mass chemical chlorine gassing in Ypres in April 1915.4

“The weatherman was right,” wrote Willi Siebert, in his later rendition of that sunny day at Ypres that would change the face of the weapons industry forever. A German gas pioneer of the First World War, Siebert was studying chemistry and pharmacology when the war broke out. Like so many young men, he traded in his studies, along with his day job selling paints and varnishes, to serve in an infantry regiment. And like many other men, Siebert looked back on Ypres with more lament than heroics: “We should have been going on a picnic, not doing what we were going to do.”

On the other side of the battle, French captain Joseph Clément thought he would spend the bright spring day recuperating in Woesten, away from the trenches. “I inspect the kitchen where the dinner simmers all gently,” Clément recalled,

It is perfect! I leave with the second lieutenants when suddenly, a bombardment bursts out. These gentlemen pricked up their ears. I reassure them by telling them that the occurrence is rather frequent. Suddenly, our guns start to roar too; then I conclude that the enemy is attacking. It is currently 4.50pm on my watch. I am in the garden of the notary listening to the infernal din of the shooting and the bombardment. At this point a smell comes upon us, which affects the throat and eyes and makes us cry. What is happening? Everyone is surprised. One looks up and we note, approaching over the canal, a greenish yellow cloud. No doubt: these are the asphyxiating gases.5

“As a novel technological development,” Jean Zanders Pascal writes, “no longstanding customary taboo on its use existed.”6 It was only after news from the trenches trickled out into the press that a broader public debate around war gases began to take shape. At first tentative and exploratory, after the Ypres bombing news and editorial headlines in the London Times read, “The Disregard of Conventions”; “The Most Damnable Invention”; “The New Phase”; “Incredible Sprits of Savagery.”7 War propaganda proclaimed the Germans savages, poison gas proof of the extent of their inhumanity. Yet it was not long before the British began their own experiments with chemical gases, as chemical retaliations for Ypres soon came. The race for more effective chemical weaponry—and defenses from it—was waged on the battlefield and in the laboratory. German innovations in chemical weapons were largely led by Fritz Haber, who began as a scientific advisor to the Kaiser before being appointed a captain in the German army, bypassing standard progression on royal dictate. At the height of perfecting poison gases, Haber had 2,000 employees working below him, 150 with chemistry degrees.

The Allies would soon follow the Germans’ lead. “The story of chemical warfare is one of imitation,” Fritz’s son Ludwig Haber later surmised in his history of gas warfare. In the United Kingdom, academic institutions, including Oxford, Cambridge, and University College London, were all enlisted to work on aspects of gas warfare. “The French,” historian Gerard J. Fitzgerald writes, “took a more direct approach to chemical weapons research by militarizing the chemistry, pathology, and physiology departments in 16 leading medical schools and institutes. Additionally, they essentially absorbed the University of Paris in order to direct, coordinate and research all aspects of chemical warfare.”8

As new gases were developed and trailed on the battlefield, their physical and psychological effects tormented soldiers and terrified the public as they encountered news of poison warfare. Historian Patrick Coffey writes, “Soldiers in the trenches found themselves constantly sniffing for gas, and a soldier in a gas mask, even if it were functioning, was half blinded, unable to aim properly or to see peripherally. And when a gas attack occurred, and the concentration of gas became so high that it began to overcome the filter and to be felt in the throat, the desire to rip the mask off and breathe deeply became almost irresistible, and some did succumb to the urge.”9

Songs and poetry recorded these horrors of gas warfare. As they circulated, they brought back home glimpses of the emotional, lived experience of suffering a gas attack. Belgian soldier-poet Daan Boens captured the grisly atmosphere in his poem “Gas,” published in 1918:

The stench is unbearable, while death mocks back.The masks around the cheeks cut the look of bestial snouts,The masks with wild eyes, crazy or absurd,Their bodies drift on until they stumble upon steel.The men know nothing, they breathe in fear.Their hands clench on weapons like a buoy for the drowning,They do not see the enemy, who, also masked, loom forth,And storm them, hidden in the rings of gas.Thus in the dirty mist, the biggest murder happens.10

As militaries scurried to engineer better protection from these poison gases, the gas mask quickly evolved. World War I soldiers used much the same ramshackle household equipment as street protesters do today. Mouth pads, helmets of different varieties, and goggles were worn to improvise the function of the gas mask in attempts to keep the poison from the skin, eyes, mouth, and nasal passages.11 Urine-soaked handkerchiefs were a common—though largely ineffectual—preventative measure. Early gas masks were clunky and uncomfortable. Describing the experience of being trapped in one, a British soldier wrote: “We gaze at one another like goggle-eyed, imbecile frogs. The mask makes you feel only half a man. The air you breathe has been filtered of all save a few chemical substances. A man doesn’t live on what passes through the filter—he merely exists. He gets the mentality of a wide-awake vegetable.”12 However insufficient, these early masks were the only defense soldiers had from poison gas. Historian L. F. Haber estimates that over 24.8 million helmets and pads were produced for British soldiers on the frontlines, along with 17.5 million respirators. For France, there were over 40.6 million helmets and pads and 5.3 million respirators.13

The Rise of the US Chemical Warfare Service

With the European chemical arms race mounting, the Americans were not long behind. Then, as now, anxiety and overcompensation defined the American war response. On the very day that the United States entered the war, it announced the formation of a Research Council subcommittee “to carry on investigations into noxious gases, generation, antidote for same, for war purposes.”14 Headquartered at American University in Washington, DC, research programs included those at MIT, Yale, Johns Hopkins, and Harvard. By July 1918 more than 1,900 US-based scientists were working on chemical warfare. Historians estimate the total number of university scientists and technicians involved globally in chemical warfare during World War I as over 5,500.15

After the war, military opinion on war gases was mixed. Many who encountered the gas firsthand argued that the inhumanity of gas had to do with the fear and anxiety it caused. Others proclaimed that gas was more humane than artillery fire as its death count was much lower. Cambridge biochemist J. B. S. Haldane argued for the efficiency of war gases, dismissing those who condemned them as sentimentalists: if one could “fight with a sword,” why not “with mustard gas”? Those who took a more holistic look at the effects of gas argued that these weapons often led men to their deaths by other means, including increased susceptibility to artillery fire. As far as military strategy went, gas warfare could only bring tactical victories. Its dependency on weather conditions left men even more at the mercy of the climate on the battlefield.

World War I historian Jean Pascal Zanders argues that two legacies emerged out of these divisive debates after the war. First, a greater distinction was made between poison gases (debated at the earlier Hague conferences) and the new chemical gases invented during the war. This semantic split would continue in arms conventions around gas warfare, offering up a legitimization for outlawing some weapons, while not others. This line of reasoning allowed tear gas to follow a different (though highly contested) legal trajectory than other poisonous agents.

Second, the commercial interests of the growing chemical industries came under consideration. Banning chemical innovations linked to wartime would hurt these burgeoning industries. With this in mind, arguments around both chemistry and chemical weapons as civilizing forces took center stage in rhetoric defending their continued developments. As the Versailles Treaty and Geneva Convention were signed after the war, the conflicted—and commercially interested—positions of the Allied countries became embedded into international agreements.

Imperial interests abroad also underpinned these justifications for the development and use of chemical agents. Policy makers differentiated between the poison of the savages and the civilized toxins of the Allied elite. Reinforcing the appropriateness for Imperial nations to deploy chemical weapons on subjects abroad, Major-General Charles Howard Foulkes, who was in charge of the British chemical warfare effort after 1915, argued, “Tribesmen are not bound by the Hague Convention and they do not conform to its most elementary rules.” True to American fashion, General Amos Fries was blunter:

Why should the United States or any other highly civilized country consider giving up chemical warfare? To say that its use against savages is not a fair method of fighting, because the savages are not equipped with it, is nonsense. No nation considers such things today. If they had, our American troops, when fighting the Moros in the Philippine islands, would have had to wear the breechclout and use only swords and spears.16

It was from this position of military superiority that the United States would go on to further develop chemical weapons, under the leadership of the vivaciously opinionated Fries.

As in Europe, in the United States both members of the public and many in the military were reluctant to see research and development into chemical warfare continue after the war. Yet a concerted lobbying effort brought millions of dollars and dozens of staff behind the Chemical Warfare Service. In an architectural as well as an ideological victory, the CWS soon built itself a new home. Edgewood Arsenal began as a modestly sized factory used for filling gas shells and producing protective masks. As the United States’ nascent chemical industry was not yet in the business of producing the chemicals used for weapons, the original military plant was modeled after bottling facilities. Builders laid track to carry in equipment as horses tugged materials across the remote fields that would soon be transformed into a large-scale military base and weapons factory. Within a matter of months, the workers at Edgewood Arsenal were producing two thousand incendiary devices a day.17

As the demand for better equipment and weaponry grew, the concrete walls and chemical facilities of Edgewood expanded. By 1920 the $35.5 million site boast...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- HalfTitle

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Chemical Warfare in World War I

- 2. War Gases for Peacetime Use

- 3. Tear Gas and the Benevolent Empire

- 4. Tear Gas and the Rise of Modern Riot Control

- 5. The Science of Making CS Gas “Safe”

- 6. Policing with Poison

- 7. Profiting from Police Use of Force

- 8. From Resilience to Resistance

- Afterword

- Notes

- Index