- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

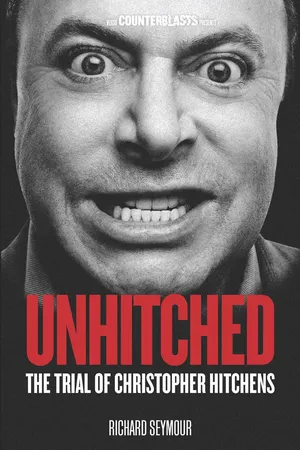

Irascible and forthright, Christopher Hitchens stood out as a man determined to do just that. In his younger years, a career-minded socialist, he emerged from the smoke of 9/11 a neoconservative "Marxist," an advocate of America's invasion of Iraq filled with passionate intensity. Throughout his life, he played the role of universal gadfly, whose commitment to the truth transcended the party line as well as received wisdom. But how much of this was imposture? In this highly critical study, Richard Seymour casts a cold eye over the career of the "Hitch" to uncover an intellectual trajectory determined by expediency and a fetish for power.

As an orator and writer, Hitchens offered something unique and highly marketable. But for all his professed individualism, he remains a recognizable historical type-the apostate leftist. Unhitched presents a rewarding and entertaining case study, one that is also a cautionary tale for our times.

As an orator and writer, Hitchens offered something unique and highly marketable. But for all his professed individualism, he remains a recognizable historical type-the apostate leftist. Unhitched presents a rewarding and entertaining case study, one that is also a cautionary tale for our times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unhitched by Richard Seymour in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Journalist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS IN THEORY AND PRACTICE

In the advanced capitalist world from the mid-1960s a generation of intellectuals was radicalized and won for Marxism. Many of them were disappointed in the hopes they formed – some of these wild but let that pass – and for a good while now we have been witnessing a procession of erstwhile Marxists, a sizeable portion of the generational current they shared in creating, in the business of finding their way ‘out’ and away. This exit is always presented, naturally, in the guise of an intellectual advance. Those of us unpersuaded of it cannot but remind its proponents of what they once knew but seem instantly to forget as they make their exit, namely, that the evolution of ideas has a social and material context.

– Norman Geras, ‘Post-Marxism?’

Marxism … had its intellectual and philosophical and ethical glories, but they were in the past … There are days when I miss my old convictions as if they were an amputated limb. But in general I feel better, and no less radical, and you will feel better too, I guarantee, once you leave hold of the doctrinaire and allow your chainless mind to do its own thinking.

– Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great

PERMANENT CONTRADICTION

One vile antithesis, a living and ignominious satire on himself.

– William Hazlitt, Sketches and Essays

The amazing, turbulent effect of the French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic wars on a certain type of intellectual led William Hazlitt to write ‘On Consistency of Opinion’. His comportment was that of a suave and slightly aloof radical raising a disconcerted eyebrow at the ‘sudden and violent changes of principle’ that these intellectuals had displayed on such trifling matters as the absolute right of the Bourbons to possess France. Wordsworth’s passage from Paineite revolutionary politics to Burkean conservatism had been a case in point. Hazlitt observed that those most susceptible to such transformations were in general not those who seemed the most yielding in argument; on the contrary, they were ‘exclusive, bigoted and intolerant’. This was because, Hazlitt proposed, those who were least capable of sympathetic investment in the points of view of others were the most likely to be hit with ‘double force’ when the unexpected happened.

This is plausible: those who are not serious in the positions they occupy are more likely to abdicate them in sudden revulsion when events test their beliefs. We can readily think of political defectors from our own era whose account of the beliefs they once held is so fantastically crude as to make one wonder how they could have been so childish – and when, if ever, they stopped being so. Yet the early Hitchens was not always lacking in interpretive charity, and he does not seem to have wholly lacked sympathy with certain right-wing tropes before his seeming volte-face.

Hazlitt went on to submit that opinions may reasonably alter over time, but there was no need to ‘discard … the common dictates of reason’. A person whose opinion has changed

need not carry about with him, or be haunted in the persons of others with, the phantoms of his altered principles to loathe and execrate them. He need not (as it were) pass an act of attainder on all his thoughts, hopes, wishes, from youth upwards, to offer them at the shrine of matured servility: he need not become one vile antithesis, a living and ignominious satire on himself.

This is instantly applicable to any number of apostate leftists – Max Eastman, James Burnham, David Horowitz, André Glucksmann, and Paul Johnson, to name only a fractional sample.

But what of the late Christopher Hitchens? Did he not swear, even as he was waving adieu and bon débarras to his former comrades, that he had not and did not repudiate his past? Was he not notable for attempting to turn the left’s language – of internationalism, justice, and even revolution – against it in the war about the war? Yes, and again, yes. But even if he did not reject his past, he most certainly travestied his principles and poured execration on those who kept the faith. His attacks on Noam Chomsky, and particularly Edward Said, had a detectable element of Hitchens’s sacrificing his past affiliations ‘at the shrine of matured servility’.

Did Hitchens hew to his old ideas like a religion, so that, having lost his faith, he could be said to have found his reason? The author allowed that the socialist politics he once espoused had had elements of religious experience but assured readers that this was all very much in his past.1 This was yet another fanciful lapse into cliché on Hitchens’s part – in this case the old anticommunist saw of The God That Failed. Not to deny that socialism has its credenda, but the beliefs that Hitchens held dearest in his postleft phase – opposition to dictatorship, support for Jeffersonian imperialism – were precisely of a sort one can assert only without proof and as articles of faith.2 What Hitchens found when he lost the socialist faith was but a Nicene Creed of liberalism.

No wonder, then, that the dominant conceit of Hitch-22, the author’s departing word on his life and his person, is that of keeping, without shame, ‘two sets of books’ – the tendency that won him the early cognomen ‘Hypocritchens’. Indeed, Hitchens delighted in inhabiting seemingly contradictory positions and defending them with distinction. Yet he simultaneously had a manifest urge to prove his consistency. It was not the complete correspondence of his earlier and later analyses that he wished to defend so much as the consistency of his rectitude. Even as he moved to the right, he remained insistently faithful to an idealised version of Orwell and Leon Trotsky, to the icons of the literary left, and to the paladins of twentieth-century resistance, from the Viet Minh to the African National Congress.

This has something to do with a familiar logic of apostasy I discussed in the prologue. Hitchens’s long-time friend James Fenton recalled the way this worked:

He had to change his mind. And in a way that for many people would be humiliating, because he was completely realigning himself. And so, a certain amount of what that was, was at a high decibel level, saying to the rest of us, ‘Well, you have changed, you’ve all changed, the Left has changed’, and so on … making it seem less obvious that his position had changed.3

That old line in effect says, ‘I didn’t leave the party; it left me.’ Throughout his career the accounts Hitchens gave of himself and his fealties conformed to this standard. Thus, for example, on leaving the International Socialists, he gave the reason that he disputed the organisation’s support for the more disreputable elements of the far left in the Portuguese Revolution and that it had embarked on a Leninist deviation from its Luxemburgist roots. Later, declaring that the era of socialism was concluded, he remarked that there was no progressive left wing worth allying with since it had sold its soul to Clintonism. At each point at which Hitchens felt compelled to move away from his former persuasions, he in some way emphasised his supposed fidelity to them.

This resulted in an accumulating mass of contradictions in Hitchens’s persona that were always managed either through solipsism – in effect, ‘I prefer my contradiction to yours’ – or by appeal to a petrified historical mandate. This makes it easy to quote Hitchens against himself – as his old friend D. D. Guttenplan put it, ‘Too easy to offer much sport’.4 Rather than sport, however, what we will look for is the contradictions amassing in Hitchens’s position, from his early revolutionism to his latter-day recusant-yet-observant posture.

THEY FUCK YOU UP: THE POLITICS OF ASPIRATION

‘If there is going to be an upper class in this country,’ Hitchens’s mother said forcefully, ‘then Christopher is going to be in it.’ By way of self-explanation he recounted this tale several times in his writing. It was his mother, Yvonne, to whom he was closer than anyone in the world, who had decided his path of advancement. Whether because of petty bourgeois ardour, or the desire of a Jewish woman to make her son ‘an Englishman’, she insisted that he be given an education otherwise preserved for ‘about one percent of the population’.5 A lower-middle-class Liverpudlian who was fond of wit, as well as booze and fags, a woman of liberal humanitarian politics, Yvonne Hitchens was ‘the laugh in the face of bores and purse-mouths and skinflints, the insurance against bigots and prudes’. ‘The one unforgivable sin’, she occasionally remarked with Wildean disdain, ‘is to be boring.’ She was also grief-stricken at the thought of anyone addressing ‘her firstborn son’ ‘as if he were a taxi driver or pothole-filler’.6

Commander Eric Hitchens bored Yvonne and seems to have been relatively forgettable to his children as well – at least for the duration of their childhood. A stoic commander in the British navy, he was a Tory with, his son suggested, nothing to be Tory about. This latter judgment rests on the idea that the Commander was ultimately a rather downtrodden victim of the class system. But it is difficult to credit. A commander in the Royal Navy is a senior officer and was always so. It is true that Hitchens describes his father as having progressed from the poorer areas of Portsmouth to the middle class via the navy. It is also true that the son tells a heartstring-plucking story of his father’s being involuntarily retired after Suez, just before the pay and pensions of new officers were increased. Yet this injustice would surely still leave Commander Hitchens with a great deal to be Tory about, and it would leave young Christopher able to attend public school and begin his ascension.7

Nonetheless, if Hitchens’s upbringing was not an impoverished one, it was insecure:

My mother in particular [urged] that the Hitchenses never sink one inch back down the social incline that we had so arduously ascended. That way led to public or ‘council’ housing, to the ‘rough boys’ who would hang around outside cinemas and railway stations, to people who went on strike and thus ‘held the country to ransom’, and to people who dropped the ‘H’ at the beginnings of words and used the word ‘toilet’ when they meant to refer to the ‘lavatory’.

This seems to have been behind Hitchens’s urge to prove himself socially, the original source of a long-standing chip on his shoulder about the establishment and his exclusion from it.8

If the Commander was a Tory, he was still ‘a very good man and a worthy and honest and hard-working one’. He was also a powerful and recurring presence in Hitchens’s life. Hitchens never pursued a military life. And he was disappointed to discover that he was not cut out to be a soldier, partly because his physical courage had limits. As a result the matter of his fortitude – mental and physical – returned as a habitual concern, as did a certain Blimpishness and instinctive reaction that he imbibed from his father. Eric ‘helped me understand the Tory mentality, all the better to combat it and repudiate it’, Christopher insisted. But the repudiation was only partial. When the Falklands were invaded by the Argentinian dictatorship, the younger Hitchens found himself outraged at the offence to British power, only to be disappointed by his father’s lack of bloodlust. Like many who wished they had fought a war, Christopher Hitchens expended his military passion through verbal bravado; his wife, Carol Blue, summarised the posture: ‘I will take some of these people out before I die.’ But this background was also responsible for some of Hitchens’s insights. When he so sensitively diagnosed the ‘John Bullshit’ that he found in Larkin’s poems and detected at the base of Thatcherism, the diagnosis was based on acute, instinctive recognition.9

So there is, in Hitchens’s formation, the beginnings of that elemental contradiction he called keeping two sets of books and the beginnings of that urge towards social climbing, the constant search for the right entrée, that led him all the way to the Jefferson Memorial, where he was naturalised as an American citizen by no lesser an American than Michael Chertoff, then secretary of the US Department of Homeland Security.

LIVING TO SOME PURPOSE: HITCHENS AND THE REVOLUTION

Hitchens began his life as a socialist while at a private school in Cambridge. A supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and of the Labour Party, he was precociously articulate. He read avidly and widely but seems to have had a preference early on for literary fiction over, for example, the social sciences, for which it seems probable he had no aptitude. He arrived at university in 1966 near the beginnings of a dramatic expansion of tertiary education in Britain. The number of college students doubled, from 100,000 to 200,000, between 1960 and 1967. Today the student population of the UK is more than two million. The inevitable result was the inclusion of some working-class youth in the expanded system, and that led to a phenomenon evident in each of the advanced capitalist societies in which the trend was registered: an intellectual radicalisation and an increasing challenge to the university authorities, symbolised in the revolt at the Sorbonne in 1968.

Oxford was not quite Paris – more Bourbon than Sorbonne – but its radical students did partake of a sustained challenge to the university authorities, the proctors, whose control of student life and maintenance of a rigid hierarchy between teacher and student was such that students today would not recognise it. Hitchens, having been a supporter of the Labour left, was recruited to the International Socialists by a psychoanalyst named Peter Sedgwick, with whom Hitchens became close.

Hitchens always recalled this period with authentic warmth. And he seems to have been highly regarded as both personable and a tremendous debater. Alex Callinicos recalls that he had an ‘easy, accessible manner … but there was a slightly ironical quality about him. One assumed that he was a rascal.’10

Yet it would be a great mistake to treat his recollections of this period as gospel. Even if he was often candid about his feelings, Hitchens was certainly capable of redaction and revision. His representation of the IS ‘groupuscule’ and its politics tended to shade the past with his present opinions. Thus, for example, it is not quite true that he was ever on the brink of becoming a ‘full-time organiser’. Former comrades recall that he was involved in the party’s bodies, and it was true that younger members were being drafted into all sorts of organising positions in order to cope with the surfeit of strikes, social struggl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: Predictable as Hell

- 1 Christopher Hitchens in Theory and Practice

- 2 English Questions, from Orwell to Thatcher

- 3 Guilty as Sin: Theophobia, from Rushdie to the War on Terror

- 4 The Englishman Abroad and the Road to Empire

- Conclusion: Twenty-Twenty Blindfold

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- About the Author

- Copyright