- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

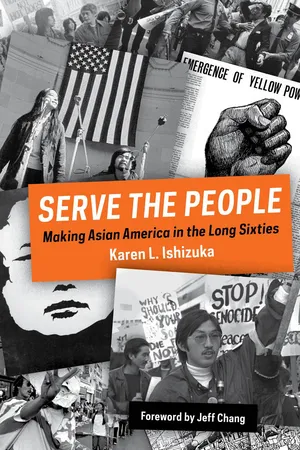

About this book

The political ferment of the 1960s produced not only the Civil Rights Movement but others in its wake: women's liberation, gay rights, Chicano power, and the Asian American Movement. Here is a definitive history of the social and cultural movement that knit a hugely disparate and isolated set of communities into a political identity--and along the way created a racial group out of marginalized people who had been uncomfortably lumped together as Orientals.

The Asian American Movement was an unabashedly radical social movement, sprung from campuses and city ghettoes and allied with Third World freedom struggles and the anti-Vietnam War movement, seen as a racist intervention in Asia. It also introduced to mainstream America a generation of now internationally famous artists, writers, and musicians, like novelist Maxine Hong Kingston.

Karen Ishizuka's definitive history is based on years of research and more than 120 extensive interviews with movement leaders and participants. It's written in a vivid narrative style and illustrated with many striking images from guerrilla movement publications. Serve the People is a book that fills out the full story of the Long Sixties.

The Asian American Movement was an unabashedly radical social movement, sprung from campuses and city ghettoes and allied with Third World freedom struggles and the anti-Vietnam War movement, seen as a racist intervention in Asia. It also introduced to mainstream America a generation of now internationally famous artists, writers, and musicians, like novelist Maxine Hong Kingston.

Karen Ishizuka's definitive history is based on years of research and more than 120 extensive interviews with movement leaders and participants. It's written in a vivid narrative style and illustrated with many striking images from guerrilla movement publications. Serve the People is a book that fills out the full story of the Long Sixties.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Serve the People by Karen L. Ishizuka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ACT II: ONCE IN A MOVEMENT

puckyoo sunn-obbaa-bit, muderrpuckkerrrrr!!Al Robles

THREE

Yellow Power

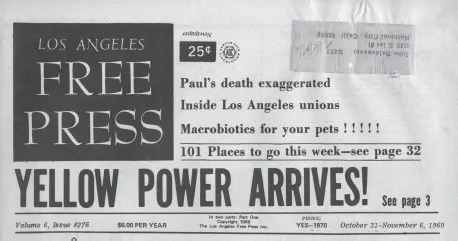

Fig. 3.1: Los Angeles Free Press, October 31–November 6, 1969

The Los Angeles Free Press (1964–78) was the first and most successful alternative newspaper of the Long Sixties. Having reached a circulation of 100,000 with a readership estimated to be double that number, it gained the reputation for being “the newspaper of the New Left” by the late 1960s.1 So when the front page of the October 31–November 6, 1969 issue of that newspaper declared “Yellow Power Arrives!” it was like having made the society page of the New Left.

Speak a New Language So That the World Will Be a New World!

Growing up Asian in a black-and-white world was a solitary experience. In our private efforts to be accepted, to be seen for ourselves, to be treated as Americans, we thought we were alone. After all, the experiences of being the only one from your Cub Scout troop to be refused entry into the public swimming pool, of realizing you too were an Eskimo, of being thrown onto the sidewalk by the seat of your pants, were mortifying. They were not things you talked about or even wanted to think about. And so we didn’t.

Nor could we even if we had wanted to. We were literally at a loss for words. Ludwig Wittgenstein remarked, “The limits of my language are the limits of my mind. All I know is what I have words for.”2 Without words, experiences and feelings can hardly be thought, much less contemplated or articulated.

If we weren’t “white,” “black,” “Oriental,” or the “model minority”—all words that defined who we were not—then what words might define who we were? The thirteenth-century Sufi poet Rumi declared, “Speak a new language so that the world will be a new world!” Since speaking is a cultural practice and language is a mode of thinking, part of the cultural revolution was linguistic.

Words became moral imperatives, reflective of the social upheaval of the times. In 1966 Lenny Bruce was arrested for saying nine “dirty” words, most of which were included in George Carlin’s 1972 monologue “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television,” in a case that made its way to the Supreme Court. “Pigs” became a common term for police. “Asshole” replaced tamer words like “phony” and “jerk,” prompting linguist Geoffrey Nunberg to note, “Put simply, you have the right to treat assholes as assholes because the assholes have it coming.”3 The term “honky,” a common pejorative since at least the 1940s, also took on a more nuanced meaning, insisting on the circuitousness of its definition. In Tom Wolfe’s prickly 1969 Esquire article “The New Yellow Peril,” he quotes San Francisco Chinatown youth organizer George Woo as saying, “I didn’t call him honky because he was white. We have some white brothers who have done some of the things we should have done ourselves. I called him honky because he was a honky.”4

Language reflected the changes that were occurring in social thinking. One of the most profound was the emergence of new terms for who we were. Tariq Modood, a leading proponent of multiculturalism, pointed out that, during the Civil Rights movement, the demand for equality was based on the assumption that we were all the same underneath our different-colored skins and that difference was a problem. The rise of Black Liberation replaced the goals of equal rights and opportunity with those of self-determination and empowerment. Difference was now valued over sameness, and the broader climate of progressive opinion recognized a multitude of groups, such as ethnic minorities, women, and LGBTQ, emphasizing identity and subjectivity. The new message was, as Modood asserted, “Respect us for what we are, don’t try and change us into your conception.”5 However, as poet June Jordan cautioned, “There is difference and there is power. And who holds the power shall decide the meaning of difference.”6

Naming thus became a critical part of the process of self-definition, as the evolution from “colored” to “Negro” to “black” to “Afro-American” to “African American” attests.7 Kwame Turé, then known as Stokely Carmichael, who popularized the concept of Black power when he was chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, first theorized the concept of self-definition with political scientist Charles Hamilton in their electrifying 1967 bestseller, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. In it they stated, “We shall have to struggle for the right to create our own terms through which to define ourselves and our relationship to the society, and to have those terms recognized.”8 Likewise, Gloria Anzaldua said that once they acquired the name Chicano and a language she calls Chicano Spanish, “the fragmented pieces began to fall together—who we were, what we were, how we evolved. We began to get glimpses of what we might eventually become.”9

Speak, Asian America!

Richard Aoki told his biographer Diane Fujino, “Up to that point, we had been called Orientals. Oriental was a rug that everyone steps on, so we ain’t no Orientals. We were Asian American.”10 Best known for being one of the few non–African American Black Panthers, the point in time that Aoki referred to was that of the formation of the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) at the University of California, Berkeley, for which he had been a spokesperson. Coined by AAPA’s founder Yuji Ichioka, the self-identifier “Asian American” marked a seismic shift in consciousness. More than just a descriptor, the term subverted the Orientalist tradition of lumping all Asians together—this time as an oppositional political identity imbued with self-definition and empowerment, signaling a new way of thinking. With the power of repetition, AAPA was the first organization to articulate the ideology of this New Man and Woman:

We Asian Americans believe that we must develop

an American Society that is just, humane, equal …

an American Society that is just, humane, equal …

We Asian Americans realize that America was

always and still is a White Racist Society …

always and still is a White Racist Society …

We Asian Americans refuse to cooperate with the

White Racism in this society …

White Racism in this society …

We Asian Americans support all oppressed peoples …

We Asian Americans oppose the imperialistic

policies being pursued by the American

government.11

policies being pursued by the American

government.11

AAPA newsletters quickly circulated to other college campuses, and other formations of the same name appeared throughout the country although they were not considered chapters of the original organization. AAPA expressed an understanding of its catalytic imperative in an October 1969 newsletter. “AAPA is only a transition for developing our own social identity … In fact, [the important link is not] AAPA itself … but the ideas generated into action from it.”12

Even as Asian American students coalesced at the University of California, Berkeley, Asian American students began organizing at its sister campus in Los Angeles. Along with developing UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, the inaugural center of this new academic discipline, many of the same undergraduates launched Gidra: The Monthly of the Asian American Experience, the inaugural newspaper of the Asian American movement. Published between April 1969 and April 1974, during the primal years of Asian America, it not only provided alternative news, it served as a national forum for vetting alternative ideas. Untethered to any one organization or ideology and being eclectically inclusive—for which it was both criticized and praised—Gidra gained a national readership and inspired the birth of many other movement newspapers.

In 1972, at a time when alternative presses were rarely taken seriously by the mainstream, Gidra caught the attention of the Library Journal, the oldest and largest trade publication for librarians, which wrote that Gidra “effectively voices this new consciousness among Amerasians, simultaneously uncovering a century of wrongs committed by the white majority and enunciating a determination to make the future at once different and better than the past.”13 As momentous as its contents were, Gidra functioned just as importantly as a Petri dish for growing oppositional consciousnesses. With over 200 volunteer “staff” over its five-year tenure and a nationwide audience, Gidra contributed to the formation of political identities that gave rise to a generational cohort of activists and cultural workers.

Poet Audre Lorde maintained that, in order to know who we are, we needed first to “train ourselves to respect our feelings and to transpose them into a language so they could be shared,” adding that, “where that language does not exist, it is our poetry which helps to fashion it.”14 Through their songs, troubadours Chris Iijima, Nobuko (then Joanne) Miyamoto and Charlie Chin were the first to transpose our untold feelings into words, fashion politics into poems, and render the politics and passion of the escalating Asian American movement into song:

I looked in the mirror,

And I saw me.

And I didn’t want to be

Any other way.

Then I looked around,

And I saw you.

And it was the first time I knew

Who we really are.15

In 1972, Chris, Nobuko, and Charlie were approached by folk singer Barbara Dane, who they got to know from singing at anti-war rallies, to record an album. The result was A Grain of Sand: Music for the Struggle by Asians in America.16 Their songs, now portable, were played at parties and rallies and sung by young and old across the country. A Grain of Sand thus became the soundtrack of the Asian American movement. Reflecting on those heady days, Charlie commented, “We were a vehicle, a delivery system to introduce people to the idea of Asian American consciousness.” Chris agreed. “I think that what we were doing was to say, ‘Look, our singing is part of what you guys are doing. Whatever you’re doing, we’re a part of that.’ Our purpose was to tell people we’re not alone.”

Yellow? Amerasia? Asian Nation?

As “Negroes” became “black” and Mexican Americans became “Chicano,” what could signify our transformation? “Yellow”? “Amerasia”? “Asian Nation”?

Before “Asian American” became standardized, we tried on different names, each reflecting reasons that were part of the process of coming to terms with who and what we were. Some of the earliest attempts to organize Asian Americans did so under the banner of “yellow,” no doubt in reaction to the color-coded black-and-white backdrop that had defined our existence.

As expressed in the 1969 LA Free Press headline, “yellow” reigned as the battle-cry of the times, an in-your-face inversion of the “Yellow Peril” and “yellow-bellied Jap” of yesteryear.17 In the summer of 1968, “Are You Yellow?” was the name of the first Asian American conference —the first of many take-offs of the 1967 Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow) that was popular at the time. In the first issue of Gidra, in April 1969, “Yellow Power!” was one of the first widely published manifestos of the new Asian American consciousness. Written by Larry Kubota, it declared:

Yellow power is a call for all Asian Americans to end the silence that has condemned us to suffer in this racist society and to unite with our black, brown and red brothers of the Third World for survival, self-determination and the creation of a more humanistic society.18

Later that same year, Gidra published “The Emergence of Yellow Power” by Amy Uyematsu, which, reprinted on the first page of the Los Angeles Free Press, bore the headline: “Yellow Power Arrives!”19 Despite its origins as an undergraduate term paper for one of the first Asian American classes, it has become the most anthologized article on the Asian American movement. As historian Scott Kurashige commented, the article “crystallized simultaneously the anger and the aspiration of [Uyematsu’s] generation.”20 The article identified four main concepts that articulated the nascent movement’s intellectual and philosophical underpinnings.

The first was the concept of identity. The supremacy of whiteness required all people of color to ruggedly declare their decolonized identity, as symbolized in the slogan “Black is beautiful.” In the words of Black Panther and AAPA spokesperson Richard Aoki, “In the past I didn’t think the identity issue was that important, but I realize that unless you have your identity, you can’t go to the political level.”21 The second notion was that Asian Americans must come into their power both personally and politically. In a vicious cycle, the normalization of inequality had led to acquiescence on the part of Asian Americans, thereby perpetuating white supremacy. Third was the significance and challenge of creating a united front, the most obvious hurdle being the multiplicity of Asian ethnicities, each with its own language, culture, and history, the diversity of which was compounded both by historical antagonisms between ethnic groups and by social and economic stratifications. The article’s fourth and last point was that, as Kubota had ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction: Wherefore Asian America?

- Act I: American Chop Suey

- Act II: Once in a Movement

- Act III: Finding our Truth

- Acknowledgments

- Illustrations Credits

- Notes

- Index