- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Vertical will make you look at the world around you anew: this is a revolution in understanding your place in the world.

Today we live in a world that can no longer be read as a two-dimensional map, but must now be understood as a series of vertical strata that reach from the satellites that encircle our planet to the tunnels deep within the ground. In Vertical, Stephen Graham rewrites the city at every level: how the geography of inequality, politics, and identity is determined in terms of above and below.

Starting at the edge of earth's atmosphere and, in a series of riveting studies, descending through each layer, Graham explores the world of drones, the city from the viewpoint of an aerial bomber, the design of sidewalks and the hidden depths of underground bunkers.

Today we live in a world that can no longer be read as a two-dimensional map, but must now be understood as a series of vertical strata that reach from the satellites that encircle our planet to the tunnels deep within the ground. In Vertical, Stephen Graham rewrites the city at every level: how the geography of inequality, politics, and identity is determined in terms of above and below.

Starting at the edge of earth's atmosphere and, in a series of riveting studies, descending through each layer, Graham explores the world of drones, the city from the viewpoint of an aerial bomber, the design of sidewalks and the hidden depths of underground bunkers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Vertical by Stephen Graham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Architecture Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One: Above

Social scientists need to raise their eyes from the groundMartin Parker

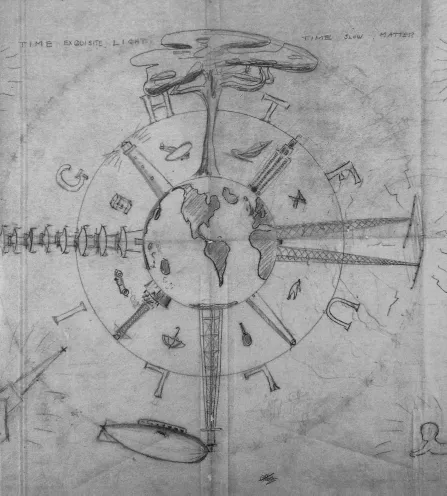

A 1928 drawing by visionary designer, architect and polymath Buckminster Fuller, emphasizing the global, spiritual, practical and vertical challenges facing engineering, architecture and human life inherent within his idea of ‘Spaceship Earth’. (Fuller, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, 1968).

1.

Satellite: Enigmatic Presence

We live in a satellite enabled age. The satellites flying above us are not abstract agents of science but part of the critical life support system we all depend on, every day.– The UK Government’s Satellites Application Catapult

There comes a point, as one ascends into the sky from the earth’s surface – and the largely upright human experience of living on it – when the conventions that surround the human experience of the vertical dimension must inevitably break down.

At the margins of the earth’s atmosphere and on the threshold of the vast realms of space we enter a world of orbits. At this point we start to encounter the crucial but neglected manufactured environment of satellites and space junk. ‘Verticality pushed to its extreme becomes orbital’, multimedia artist Dario Solman reflects. At such a point ‘the difference between vertical and horizontal ceases to exist’. Such a development brings with it profound and unsettling philosophical challenges for a species that evolved to live upright on terra firma. ‘Every time verticality and horizontality blend together and discourses lose internal gravity’, Solman argues, ‘there is a need for the arts.’1

The earth’s fast-expanding array of around 950 active satellites – over 400 of which are owned by the United States – are central to the organization, experience – and also the destruction – of contemporary life on the earth’s surface. And yet it remains difficult to visualise and understand their enigmatic presence.2 Mysterious and cordoned-off ground stations dot the earth’s terrain, their futuristic radomes and relay facilities directed upwards to the satellites above. Small antennae lift upwards from a myriad of apartment blocks to silently receive invisible broadcasts from transnational television stations. Crowds might even occasionally witness the spectacle of a satellite launch atop a rocket.

Once aloft, however, satellites become distant, enigmatic and, quite literally, ‘unearthly’.3 At best, careful observers of the night’s sky might catch the steady march of mysterious dots across the heavens as they momentarily reflect the sun’s light. Such a small range of direct experience fails to equip us with the skills to disentangle the politics of this huge aerial assemblage of circling and (geo)stationary satellites.

It doesn’t help that the literature on satellites in the social sciences is startlingly small. Communications scholars Lisa Parks and James Schwoch suggest that this is because scholars, too, struggle to engage with satellites because they lie so firmly beyond the visceral worlds of everyday experience and visibility. ‘Since they are seemingly so out of reach (both physically and financially)’, they point out, ‘we scarcely imagine them as part of everyday life’ at all. 4

As we saw in the introduction, the continued tendency of many scholars of the politics of geography to maintain a resolutely horizontal view compounds our difficulties in taking seriously crucial the roles of orbital geographies in shaping life (and death) on the ground. Only very recently have critical geographers started to look upwards to the devices circling our Earth in their first tentative steps towards a political geography of inner and outer space.

Such a project emphasises how the regimes of power organised through satellites and other space systems are interwoven with production of violence, inequality and injustice on the terrestrial surface.5 But it also attends to the importance of how space is imagined and represented as a national frontier; a birthright of states; a sphere of heroic exploration; a fictional realm; or as a vulnerable domain above from which malign others might stealthily threaten societies below at any moment.

The invisibility of the earth’s satellites and their apparent removal from the worlds of earthly politics has made it very easy to place their organization and governance far from democratic or public scrutiny. Such a situation creates a paradox. On the one hand, widening domains of terrestrial life are now mediated by far-above arrays of satellites in ways so fundamental and basic that they have quickly become banal and taken for granted – when they are noticed or considered at all.

Global communications, navigation, science, trade and cartography have, in particular, been totally revolutionised by satellites in the last few decades. Military GPS systems, used to drop lethal ordnance on any point on Earth, have been opened up to civilian uses. They now organise the global measurement of time as well as the navigation of children to school, yachts to harbours, cars into supermarkets, farmers around fields, runners and cyclists along paths and roads and hikers up to mountaintops. Widened access to powerful imaging satellites, similarly, has allowed high-resolution images to transform urban planning, agriculture, forestry, environmental management and efforts to NGOs to track human rights abuses.6

Digital photography from many of the prosthetic eyes above the Earth, meanwhile, offers resolutions that Cold War military strategists could only dream of – delivered via the satellite and optic fibre channels of the Internet to anyone with a laptop or smartphone. A cornucopia of distant TV stations are also now accessible through the most basic aerial or broadband TV or Internet connection. Virtually all efforts at social and political mobilization now rely on GPS and satellite mapping and imaging to organise and get their message across.

Satellites, in other words, now constitute a key part of the public realms of our planet. The way they girdle our globe matters fundamentally and profoundly. And yet satellites are regulated and managed by a scattered array of esoteric governance agencies. They are developed and engineered by an equally hidden range of state and corporate research and development centres. When the obsessive secrecy of national security states is added to this mix, it becomes extremely hard to pin down even basic information about the ownership, nature, roles and capabilities of these crucial machines orbiting the Earth.

Such a situation has even led media theorist Geert Lovinck to suggest that it is necessary to think of the figure of the satellite in contemporary culture in psychoanalytical terms – as an unconscious apparatus that lurks away from and behind the more obvious or ‘conscious’ circuits of culture.7 ‘Publics around the world have both been excluded from and/or remained silent within important discussions about [the] ongoing development and use [of satellites]’, Parks and Schwoch stress. ‘Since the uses of satellites have historically been so heavily militarised and corporatised, we need critical and artistic strategies that imagine and suggest ways of struggling over their meanings and uses.’8

‘Ultimate High Ground’

Space superiority is not our birthright, but it is our destiny … Space superiority is our day-to-day mission. Space supremacy is our vision for the future.– General Lance W. Lord, commander of the

US Air Force Space Command, 2005

Even a preliminary study of the world of satellites must conclude that they have contributed powerfully to the extreme globalization of the contemporary age. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the murky and clandestine worlds of military and security surveillance satellites. Not surprisingly, the idea of colonizing inner space with the best possible satellite sensors has long made military theorists drool. Their pronouncements revivify long-standing military assumptions that to be above is to be dominant and in control in the campaign to subjugate enemies.

The extraordinary powers of globe-spanning military and security satellites are only occasionally hinted at by whistleblowers or leaks. By communicating details about the earth’s surface to secretive ground stations – its geography, communications, inhabitants and attributes – and by allowing weapons like drones to be controlled anywhere on Earth from a single spot, military and security satellites produce what geographer Denis Cosgrove called ‘an altered spatiality of globalization’.9

Peter Sloterdijk stresses the way the increasing dominance of the view of the earth from satellites since the 1960s has revolutionised human imagination about the earth through a form of what he calls ‘inverted astronomy’:

The view from a satellite makes possible a Copernican revolution in outlook. For all earlier human beings, gazing up to the heavens was akin to a naive preliminary stage of a philosophical thinking beyond this world and a spontaneous elevation towards contemplation of infinity. Ever since the early sixties, an inverted astronomy has … come into being, looking down from space onto the earth rather than from the ground up into the skies.10

This sense of global, total and seemingly omniscient vision from above allows military satellite operators in particular to render everything on the earth’s surface as an object and as a target, organised through near-instantaneous data transmission linking sensors to weapons systems.11

Crucially, such ‘virtual’ visions of the world, wrapped up in their military techno-speak acronyms and euphemisms, are stripped of their biases, selectivity, subjectivity and limits. The way in which they are used to actively and subjectively manufacture – rather than impassively ‘sense’ – the targets to be surveilled, and, if necessary, destroyed, is consequently denied. A further problem, of course, is that satellite imaging efforts also completely ignore the rights, views and needs of those on the receiving end of the technology on the earth’s surface, far below satellite orbits – the people who are most affected by the domineering technology above. As with the closely allied worlds of the drone, military helicopter or bomber to be discussed in subsequent chapters, this imperial trick works powerfully. It manufactures the world below as nothing but an infinite field of targets to be sensed and destroyed, remotely, on a whim, as deemed appropriate by operators in distant bunkers. ‘All the various aspects of satellite imagery systems … work together’, writes communications scholar Chad Harris. They do this, he says, to create and maintain ‘an imperial subjectivity or “gaze” that connects the visual with practices of global control.’12

To deny how constructed and subjective satellite visioning is, militaries and security agencies represent it as an entirely objective and omniscient means for a distant observer to represent the observed. This God-like view of satellite imagery is often invoked by states as evidence of unparalleled veracity and authenticity when they are alleged to depict weapons of mass destruction facilities, human rights abuses or nefarious military activities.

It does not help that many critical theorists mistakenly suggest that contemporary spy satellites effectively have no technological limitations or that a hundred Hollywood action movies – erroneously depicting spy satellites as being capable of witnessing anything – do the same. Critics often depict satellite surveillance as being omnipotent and omniscient – a world of complete dystopian control with no limits to the transparency of the view and no possibilities for resistance or contestation.13 In suggesting, for example, that ‘the orbital weapons [and satellites] currently in play possess the traditional attributes of the divine: omnivoyance and omnipresence’, French theorist Paul Virilio radically underplays the limits, biases and subjectivities that shape the targeting of the terrestrial surface by satellites.14

Instead of invoking satellites as an absolute form of imperial vision, it is necessary, rather, to see satellite imaging as a highly biased form of visualizing or even simulating the earth’s surface rather than some objective or apolitical transmission of its ‘truth’.15 It is also, as we shall see, necessary to stress the potential that satellites have for those challenging military-industrial complexes, environmental and human rights abuses and all manner of political and state repression.

Where maps are now widely understood to be subject to bias and error, satellite images are still widely assumed to present a simple, direct and truthful correlation of the earth. This occurs even when there is a long history of such images being so imperfect and uncertain – and as so manipulated, mislabelled and just plain wrong – that it necessary to be sceptical of such claims.16 us military theorists offer an excellent case study of how attempted domination of satellite sensing is being combined with long-standing metaphors about the strategic power of being above one’s enemies. In 2003 the US RAND think-tank declared that space power and its attendant satellites offered the ‘ultimate high ground’ in struggles for military superiority.17

The US military’s vision for dominating space is characterised by dreams of being able to see anything on the earth’s surface at any time, regardless of enemies’ efforts to occlude their targets.18 This ambition is linked with an obsession with the ability to use GPS satellites to organise the dropping of lethal ordnance on those self-same spots. Satellite dominance is seen as a critical prerequisite to the dominance of the airspace, landspace and maritime space below.

Finally, satellites are considered by US military theorists to be a crucial means of reducing the vulnerability of the home nation. This ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface: Dubai, January 2010

- Introduction: Going Vertical

- Part One: Above

- Part Two: Below

- Afterword

- Notes

- Acknowledgements

- Index