eBook - ePub

The Oil Road

Journeys from the Caspian Sea to the City of London

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In a unique journey from the oil fields of the Caspian Sea to the refineries and financial centres of Northern Europe, James Marriott and Mika Minio-Paluello track the concealed routes along which flows the lifeblood of our economy. The stupendous resource of Azerbaijani crude has long inspired dreams of a world remade. From the revolutionary Futurism of the capital city, Baku, in the 1920s to the unblinking Capitalism of modern London, the drive to control the region's oil reserves-and hence people and events-has shattered environments and shaped societies.

In The Oil Road, the human scale of village life in the Caucasus Mountains and the plains of Anatolia is suddenly, and sometimes fatally, confronted by the almost ungraspable scale of the oil corporation BP. Pipelines and tanker routes tie the fraying social democracies of Italy, Austria and Germany to the repressive regimes of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. A web of financial and political institutions in London stitches together the lives of metropolis and village.

Building on a decade of study with Platform, Marriott and Minio-Paluello guide us through a previously obscured landscape of energy production and consumption, resistance and profit that has marked Europe for over a century. They blend the empathy of committed travel writing with the precision of investigative journalism in a timely book of compelling urgency.

The human race travels the Oil Road, and this book helps us to realize where we are heading and why it is time to change direction.

In The Oil Road, the human scale of village life in the Caucasus Mountains and the plains of Anatolia is suddenly, and sometimes fatally, confronted by the almost ungraspable scale of the oil corporation BP. Pipelines and tanker routes tie the fraying social democracies of Italy, Austria and Germany to the repressive regimes of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. A web of financial and political institutions in London stitches together the lives of metropolis and village.

Building on a decade of study with Platform, Marriott and Minio-Paluello guide us through a previously obscured landscape of energy production and consumption, resistance and profit that has marked Europe for over a century. They blend the empathy of committed travel writing with the precision of investigative journalism in a timely book of compelling urgency.

The human race travels the Oil Road, and this book helps us to realize where we are heading and why it is time to change direction.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Oil Road by James Marriott,Mika Minio-Paluello in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Energy Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I THE WELLS

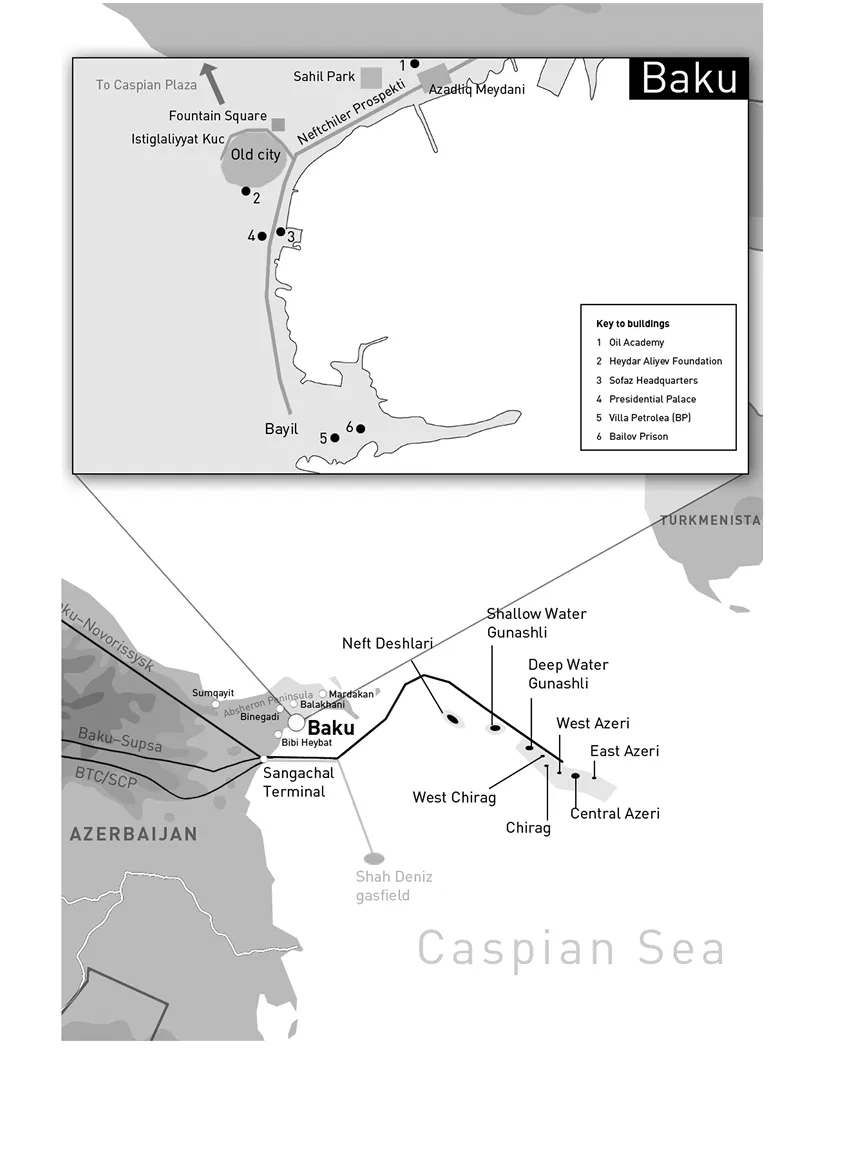

MAP II WESTERN CASPIAN AND AZERBAIJAN

1 IT HAS TO BE THE CASPIAN

0 KM1 – CENTRAL AZERI, ACG, AZERBAIJAN

Frazer dangles on a rope from the rig high above the steel-blue swell. Below him, three of his six-man team abseil off the platform, checking for corrosion. The strengthening sun makes Frazer’s red overalls tight and irritating. His tattooed arms and back run with sweat. To make the work a little less routine, he gently pulls on the rope of his colleague below, and then lets go. The body beneath jerks suddenly; there is a gasp, and a stream of expletives rises up towards Frazer. He laughs.

It is shortly after dawn. Activity on the oil platform slowly increases before the real heat of the day. Over 100 kilometres east of Baku, but only 10 from the territorial waters of Turkmenistan, Frazer is at work over the treasure house of Azerbaijan: the Azeri–Chirag–Gunashli oilfield, known as ACG. A few metres above his head is the 16,000-tonne steel deck of the Central Azeri no. 1 platform, covering an area of several football pitches. Built on top of it are six storeys of utilities and living quarters, piled nearly 30 metres over the sea. The drill tower, like the spire of a cathedral, rises far into the air. Shooting out from the side of the main deck, an arm raised in salute, is the flare stack, burning off the gas, a roaring burst of orange flame, brilliant both in brightest day and darkest night. The fire from beneath the sea.

Shift follows shift, day in, day out; this mine never rests. The staff on the platform come here from all corners of the globe, flying in to Baku’s Heydar Aliyev International Airport before being shuttled out to Central Azeri by helicopter. This labour force operates a platform that, although in Azeri waters, abides by the habits and culture of the Western oil companies, following practices largely evolved in the North Sea.2 English is the language, and dollars the currency, on this Scots offshore island.

Central Azeri is one of seven platforms in the ACG oilfield. Looking north-west, Frazer can see the lights of the twin structures of Deep Water Gunashli, ten kilometres away. Between them and him rise the solo towers of Chirag 1 and West Azeri, while away to the south-east lies the lone East Azeri. All but one of these seven mountains of steel were built on a more or less identical model. The one that stands distinct is Chirag, which was partially constructed by the Soviet oil industry in the 1980s and only completed by BP and other Western companies in 1997.

The main platforms were manufactured in ready-made sections in Norway. They were transported down the Volga Canal by barge and across the Caspian Sea to Azeri rig yards south of Baku. Here the sections were assembled and then towed out to sea, guided to their precise locations by satellites. Each pair of support legs was tipped and lifted by cranes mounted on barges, until they stood upright in 120 metres of water. Seven hundred thousand tonnes of components – gas turbines, valves, cables, pumps and linepipe – were transported here by ship, train, truck and plane. With 3,000 orders from around the world, it was like building a space station in orbit.3 Now complete, these monuments – weathered by the sun and sea – have to be checked by Fraser and ‘his boys’ for rust.

At the heart of Central Azeri, as with the other platforms, is the drilling unit, from which the drill itself plunges to the floor of the Caspian and then down another five kilometres to the oil-bearing rocks of the Lower Pliocene sandstone layer. Through a complex web of valves on the seabed, the seven platforms operate sixty oil wells in the ACG field, drawing up Azeri Light crude formed between 3.4 and 5.3 million years ago.4

The hydrocarbons are made from plankton and plants that thrived long before Homo sapiens evolved. These organisms stored the energy of sunlight from the Tertiary period; now their fossilised and compressed remains are penetrated by the drills and, under immense geological pressure, rush up through the risers to the platforms. The oil industry is built on the extraction of these long-dead ecosystems, and the Oil Road is constructed to distribute ancient liquid rocks so that our one species may live beyond the limits of the ecosystems of our times.

This extraction and distribution of geology is a high-risk process. Oil always comes from the deep mixed with natural gas – known as associated gas – which can be as unpredictable as the sea that thunders against the platform’s legs. Gas can accumulate in the risers in great bursts that strain the steel structure. And it can leak, so that one chance ignition turns a platform into an inferno. Early in the morning of 17 September 2008, the alarms on Central Azeri blared and the air was filled with the thunder of helicopters.5 Sensors had detected a gas leak below the installation, and when workers looked down at the sea they noticed bubbles on the surface. It was a potential disaster. All the 210 personnel were evacuated, and the platform was shut down. Extraction in the ACG field fell from 850,000 barrels of oil per day to 350,000, incurring a daily loss of $50 million in income. How would it have been if the platform had blown, like BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig in the Gulf of Mexico a year and a half later? The spill from that disaster would have covered much of the Caspian.

As morning work starts on the oil platforms we are standing at the dockside in Baku, squinting at the eastern sea. The view is clear, but Central Azeri is far beyond the horizon.

We study a map obtained from a former diver on ACG, despite the restrictions on information and data about the oil installations. It shows a demarcated zone, roughly rectangular, approximately forty-two kilometres long by eight kilometres wide. This is the PSA Area, the sea space defined by the 1994 Production Sharing Agreement, promoted as the ‘Contract of the Century’, signed by the Azeri government and the private-sector Azerbaijan International Operating Company led by BP. This is the area of the wells, just over 330 square kilometres of designated industrial zone far out in the wildness of the Caspian. Azeri territory under the control of a foreign oil consortium.

We have come to Baku by train and bus to start upon the Oil Road from the Caspian to Germany. Many places along the way are familiar from past visits over the last twelve years, but now we want to travel the route in a continuous journey. Our few days in this city will be filled with a round of interviews that will help illustrate how the oil wells at the beginning of this road were sunk in this country.

It has long been our desire to start with an exploration of the offshore platforms. We have considered it from every angle. But there is no ferry that travels to the area, and to hire a vessel for the130 kilometres out to sea and back would be immensely tricky. Trying to charter a boat would arouse suspicions with the authorities, and we have little doubt that we would be arrested if we approached the platforms. Only those few Azeris employed by the oil companies visit this zone, which is widely understood to be the goldmine of the nation. More than 65 per cent of the country’s oil production comes from here.6

The Azeri–Chirag–Gunashli oilfield is not shown on maps of Azerbaijan. There is no trace of the installations and flares as we search on Google Earth. We have less than thirty photographs of it on our laptop, and all of these are promotional images published by BP. Each one is either a distant photo of a gleaming white platform rising from a calm blue sea, or a closer shot of some unidentified steel structure with men working in orange or red jumpsuits, BP logo on their breasts, wearing white hard hats with an AIOC logo on the crown.7 These are photos from some other place, of clean orderliness, of uniformed men in a machine world. Like images of a space station rather than an oil well.

Like many places on our journey, the wells lie in a forbidden zone to which only our imaginations can travel. We met Frazer on the train from Baku to Tbilisi a while back, heard his stories of the platforms, and, through careful research, have tried to build the truest picture that we can. We know we will have to do the same for other places on this route, places that impact heavily on the lives of so many people, but are hidden from the world.

The countries through which we are travelling are portrayed in books and music, film and websites – they exist in the world’s imagination. Yet the route we are following is obscure. It is described only in technical manuals and industry journals, data logs and government memos.

The journey along this Oil Road echoes those along the Silk Road. The passage through Central Asia was passed to the Western European mind by the likes of the Venetian merchant, Marco Polo. The fantastical things that he reported fed centuries of debate about the authenticity of his travels. Following in Polo’s footsteps, there are places that we long to visit and yet are beyond the realm of the possible, places of which we have to construct images from the tales of others, such as Frazer.

So, keen sailors that we are, frustrated at the Baku dockside, we set about describing a journey by boat from the Central Azeri platform to the point where we stand. Tracing our fingers across the map from the diver and a sea chart, we work out the narrative of our passage.

If we were to sail from beneath the platform, a rising north-easterly wind could drive us west-north-west, and the waves would pick up as we pushed against the prevailing current. After seven kilometres we would cross an invisible line and begin to leave the PSA area. To our starboard we would see the outline of Deepwater Gunashli, the last of the platforms to come onstream, in April 2008.

Before these platforms could be built, the political, legal and financial conditions for their creation had to be established. From initial meetings in May 1989, it took nineteen years to reach the point when oil was extracted from ACG at the rate that was planned. In the five years after the first meetings, competition for contracts for the oilfield was dominated by a number of businesses, mainly from Britain (BP and Ramco) and the US (Amoco, Unocal and Pennzoil). Eventually the signing of the 1994 ‘Contract of the Century’ brought these actors into the alliance of the Azerbaijan International Operating Company, a consortium of eleven corporations including BP, Amoco, Lukoil of Russia, and the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR).

It is this consortium that controls the forbidden zone and the platforms. The membership of the AIOC has fluctuated over time as fortunes have changed. When the contract was signed, BP held a 17.1 per cent stake. Within a few years, after merging with Amoco, the combined company owned a controlling 34.1 per cent. Since the project’s outset, BP has been the main player, known as the Operator. BP Exploration Caspian Sea Ltd oversees the corporation’s endeavours in Baku. The president of BP Azerbaijan, Bill Schrader, is also the president of AIOC.

From the dockside we gaze at the city around the curve of the bay. To the south, we can see buildings clustered on the headland of Bayil. Hidden among them is Villa Petrolea, the headquarters of BP in Azerbaijan, where Schrader’s office is located. The steel structures offshore in the Caspian did not rise from the seabed by some force of nature but through the actions of people – mostly men – and through a myriad of decisions taken over a twenty-year period. The construction of the platforms was driven by geopolitical power and capital, and these forces engulf individuals such as Frazer or Schrader; although that is not to say that those individuals could not have acted differently, or made different decisions that would have altered the course of events. Our intention as we journey along the Oil Road is to meet those who have helped to create it. But, as with the platforms in the forbidden zone, it is difficult to gain access to some of these actors, so we will build a picture of their role in events through newspaper reports, company publications, memoirs, histories and official documents obtained through Freedom of Information requests.

Central among those who helped create the road was John Browne, chief executive of BP. His autobiography describes his first visit to the Azeri capital in July 1990:

I drew back the thin curtains in a grim Baku hotel room to watch the sun rise over the grey Caspian Sea. Hundreds of feet below that still water, in a stretch called the Absheron Sill, lay the promise of billions of barrels of premium oil. Azerbaijan had been lost behind the Iron Curtain for many years. Many assumed Caspian resources had dried up because the Soviets had abandoned drilling almost completely. I had come to find out how BP could secure a deal to extract what promised to be a sizable prize. I had little idea what twists and turns the venture would take. And I would become embroiled in the formation of a strategic East–West energy corridor: even Washington would become involved. The venture would even loosely inspire a James Bond film.8

The previous year, in March 1989, Browne, then chief executive of US BP subsidiary SOHIO, was promoted. He was moved to BP’s head office in the City of London, becoming chief executive of Exploration and Production – the most profitable wing of the company. With him came trusted lieutenants, including Tony Hayward, who would later lead BP into the Deepwater Horizon spill disaster.

By the time of this appointment, Browne was already renowned as an ‘eighteen hours a day man’, and had built up a strong repu...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TITLE

- COPYRIGHT

- EPIGRAPH

- CONTENTS

- FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- GLOSSARY

- PROLOGUE: THE OIL CITY

- PART I THE WELLS

- PART II THE ROAD

- PART III THE SHIP

- PART IV THE ROAD

- PART V THE FACTORY

- EPILOGUE: THE OIL CITY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Index