eBook - ePub

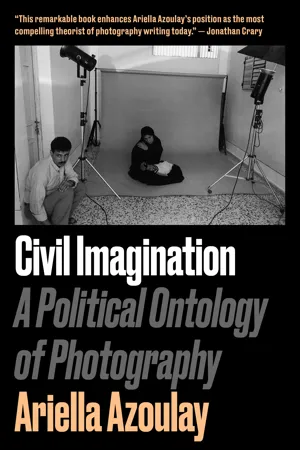

Civil Imagination

A Political Ontology of Photography

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The photograph is not just an image but an event, one in the longer sequence of a photographic moment. Challenging given definitions of photography and of the political, Ariella A?sha Azoulay calls for us to use photographs of political violence, such as the colonial regime in Palestine, to envision the political relationships that made each photograph possible, and to be able to intervene in them. In this way, we can build our capacity for "civil imagination": a way of seeing and imagining ourselves as part of the image rather than only as spectators.

The new edition includes a discussion of the legal battles to reclaim the images of the enslaved Papa Renty, held by Harvard University, rejecting the regime of photographs as private property, established by institutions that claim ownership of images seized with violence.

"This trenchant, perennially contemporary book valorizes powerful intersubjective relations enabled by photography, relations that exceed the strictures of imperial power. For Azoulay, photography's entangled temporalities enable a transformation of our sense of what persists, just as a collective practice of civil imagination reconstructs our apprehension of those with whom we unevenly share a lifeworld. Azoulay contradistinguishes spectatorship from the radical work of being a companion- a distinction that itself rewrites normative conceptions of the social work of seeing." - Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, author of Dark Mirrors

The new edition includes a discussion of the legal battles to reclaim the images of the enslaved Papa Renty, held by Harvard University, rejecting the regime of photographs as private property, established by institutions that claim ownership of images seized with violence.

"This trenchant, perennially contemporary book valorizes powerful intersubjective relations enabled by photography, relations that exceed the strictures of imperial power. For Azoulay, photography's entangled temporalities enable a transformation of our sense of what persists, just as a collective practice of civil imagination reconstructs our apprehension of those with whom we unevenly share a lifeworld. Azoulay contradistinguishes spectatorship from the radical work of being a companion- a distinction that itself rewrites normative conceptions of the social work of seeing." - Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, author of Dark Mirrors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Civil Imagination by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Louise Bethlehem in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS PHOTOGRAPHY?

The Ontological Question

The most frequent response to the above question—What is photography?—is latent in the etymology of its name and recurs from the very inception of photography until the present, or at least until the advent of digital photography. In this etymology, photography is a “notation in light.” Writing in light is what transpires when the camera shutter opens and light rays, reflected off that which stands in front of the camera, penetrate the lens and are inscribed upon a certain surface.1 Henry Fox Talbot, one of the inventors of the technology known as photography, also known by other names such as the “calotype” or the “talbotype” at this time, underscored this characterization of photography in the title of his book, The Pencil of Nature, published in 1844.2 Talbot directed our attention to the question of agency, which distinguishes photography from previous methods of image production. In the place of an individual artists possessed of certain talents and aptitudes, nature now inscribes itself by itself. The term “nature” serves Talbot as a general designation for the referent of the image. Predictably, it gave rise to criticism among those seeking to explicate photography, not because of the use that Talbot made of the word “nature,” but because of his elimination of the human agent and his presentation of photography as a medium for the production of images without human intervention.3 However, Talbot, a photographer whose work features in this book, did not in fact seek to eliminate the human agent.4 He sought instead to offer an alternative description to the prevailing notion of the omnipotent creator who with the stroke of his brush translates his object of reference into an image possessing a certain impact. Talbot’s description moves the emphasis away from the owners of the means of production and points to the potential latent in the capacity of the new technology to deviate from the familiar forms of image production, which assumed a singular author.5 His position was, however, misunderstood, as if all that was at stake in his discussion was a technology that seems to act in its own right. His opponents differed from one another yet shared a common motivation: to undermine the assumption that the “pencil” could direct itself. There were those who saw photography as an unreliable medium and the photographer as constantly manipulating reality through the photograph so as to reflect his or her biased point of view. On the other hand, there were others, eager to preserve the photographer’s prestige, who insisted that its unique contribution—its artistry—did not result from the technical activation of the apparatus. While the debate raged, a growing number of enthusiasts and technicians of photography continued to make use of photography as photographers, as photographed persons, and as spectators of different fields of knowledge and action. Until the shift occasioned by the development of visual culture as an academic discipline during the last two decades of the twentieth century, however, the contributions of such amateurs were not deemed worthy of investigation, nor of conceptualization as an integral part of the practice of photography.

Talbot’s stance, which undermined the status of the author of the photograph, eventually lost its advocates. What was left of this position in a debate that slowly receded was Talbot’s emphasis on technology. Certain adherents of Talbot’s position investigated the technology in their own right, but they did not present the technology of photography as functioning autonomously, seeing it instead as a form of technology operated by the photographer. The distance between the two opposing forms of objection to Talbot’s position diminished until they could no longer be termed oppositional at all. Thus, for approximately 150 years, photography was conceptualized from the perspective of the individual positioned behind the lens—the one who sees the world, shapes it into a photograph of his own creation, and displays it to others. Paradoxically, something of the position that Talbot originally represented, devoid of defenders for a long period of time, emerged in the form of a kind of primitive poetic residue distilled from the arguments of his opponents, as in Roland Barthes’ celebrated notion of the “punctum,” for instance. Barthes sought to use the notion of the punctum to undermine the centrality of the singular photographer, the uncontested ruler of what Barthes terms the “studium” of the photograph, where the punctum figures as a kind of residue neglected by the photographer.

The emaciation of the ontological perspective latent in the title of Talbot’s book and the narrowing of his argument by his opponents, or those who pretended to argue with it so as to make it encompass merely those aspects of photography that rendered it an autonomous technology, enabled, in turn, the emergence of a no less reductive position—one centering this time around the subject who commands the technology of photography like clay in the hands of the potter. Research into the technology of photography saw the ontology of photography in this light, whereas research into photographic oeuvres and their creators, modeled on the familiar protocols of art or the history of art, took the place of the political question: What characterizes the new relations that emerge between people through the mediation of photography? In both instances, from the moment that photography began to be diffused in the world, it was seen as a discrete technology possessing a clear purpose—the production of images—and it was delineated as a circumscribed technology whose field of action is subjugated to the activating gesture of its users.

These were the conventional boundaries within which it was possible to think about photography until the end of the twentieth century: a technology for the production of images operated by a singular subject—technician, creator or manipulator.6 Admittedly, the fact that photography deviated from its predecessors was not overlooked: this is precisely what is central to Talbot’s position—that which is positioned in front of the lens “was there” and is inscribed in and of itself on a surface coated with some kind of chemical. But very few thinkers exploited the radicalism of the insight or dared to think through the tradition of image production in a critical fashion. Among them, we may number Walter Benjamin, who associated photography with forms of mechanical reproduction rather than with drawing and who described the shift entailed in the perceptual system by the advent of photography. Another voice in this trajectory is that of Thierry de Duve whose discussion of the tube of industrial paint surprisingly links painting to the tradition of technology, and sees it from this industrial perspective as the forerunner of photography. But even these dissident thinkers were not fully able to undermine the productive/creative framework that continued to organize thought concerning photography.

It is difficult, perhaps even incorrect, to point to a specific moment or event responsible for overturning the canonical framework of the discourse of photography. But it is easy to point to a series of actions that demonstrate that this framework has recently been ruptured, allowing new questions such as “What is a photograph?” to surface and to elicit answers. Tens of exhibitions, Internet forums, conferences and journals have, over the last twenty years, celebrated photography as a phenomenon of plurality, deterritorialization and decentralization. Photographic archives that had been collecting dust for years in psychiatric hospitals, prisons, state and municipal institutions, hospitals, interrogation facilities, family collections or police files, unremarked upon by scholars of photography, as well as the notion and institution of the archive itself instantaneously became a privileged object for research and public exhibition.7 The wealth and variety contained in these collections transformed the canonical discourse on photography, a discourse that had emerged in the shadow of the discourse of art that consecrated sovereign creators and that considered photography from the perspective of its creators alone. In the wake of this shift, the perspective associated with the discourse of art was transformed into merely one possible point of entry into the study of photography, and a particularly limited one at that. It is only fair to point out that the limitations with which I am concerned here characterize a certain type of discourse about photography, rather than the practice of photography itself, whose actual activities deviated markedly from the rarefied practice conceptualized and presented as the corpus of photography; just as what was photographed always exceeded the constructs that sought to contain them as the object of reference. The many users of photography, only a small portion of whom operated under the patronage of the canonical discourse on photography, never ceased inventing new forms of being with others through photography. After the shift in photographic interest, some commentators began to address the emergence of such practices, although for the most part their output still tended to remain derivative of the products they investigated, that is to say, bound to the particular photographs accumulated. The photographs themselves continued to set the boundaries of the discussion of photography and allowed for the preservation of the causal connections between the action of photography and the photograph. In other words, photography remained conditional on the existence of the photograph. For my own part, I would like to base myself on the unprecedented wealth of photographs that emerged into view once the boundaries of the discourse on photography had been ruptured, in order to demonstrate that the ontology of photography is, fundamentally, political.

As I have already stated, until the shift of boundaries outlined above, photography was conceptualized as a technology that allowed for the inscription of an image in light, while at the same time, the very technology itself was assumed to remain transparent without leaving its imprint on the final product. The coherence of such a description requires that photography be placed at the service of two masters—the photographer who employs it and the photograph that is the end goal of his activity, while all other traces are eliminated from the final product. When these traces persisted as visible imprint, nevertheless, their sheer presence was enough to disqualify the photograph or the photographer. Few practitioners in the past sought to foreground such traces, but early examples of such foregrounding do exist. In recent decades, ever since technological mediation began to become visible, it was no longer possible to conceive of the technology as external and separate from the product that produced it. It was now a relatively short path to the recognition that the technology of photography is not just operated by people but that it also operates upon them. The camera was no longer just seen as a tool in the hands of its user, but as an object that creates powerful forms of commotion and communion. The camera generates events other than the photographs anticipated as coming into being through its mediation, and the latter are not necessarily subject to the full control of the agent who holds the camera. The properties and nature of the camera could now suddenly emerge into public view, and it rapidly became apparent that the camera possesses its own character and drives. The camera might, at times, appear to be obedient, but it is also capable of being cunning, seductive, conciliatory, vengeful or friendly. It can be woefully unarmed with information, can magnify the achievements of amateurs, and can destroy the work of master craftsmen. The camera is an opaque tool that does not expose anything of its inner workings. It is difficult for anyone who sees it from the outside in real time to know what it is inscribing, if it is indeed inscribing anything at all. Similarly, it is difficult to establish with any certainty whether the camera is present or absent, whether it is switched on or off, whether it is indeed producing images when it is switched on, whether this is its only effect, or whether its goal might, among other things, consist precisely in hiding its very agency. Does the camera appear to be active when it is actually dormant, or does it create dormancy while actually operating or better still, while being operated? Rather than being considered a device whose presence was totally occluded in favor of its products, which themselves circumscribed the boundaries of the gaze restricting it to the circumference of the frame, the camera—and together with it, the act of photography—now assumed the status of a significant catalyst of events only part of whose impact was contained in the possibility or threat of a writing in light.

Lemon cameras, negative 4×5 B/W, 5×4 box, perforated black cardboard. Photograph by Aïm Deüelle Lüski. Tel Aviv Museum Collection, 1977

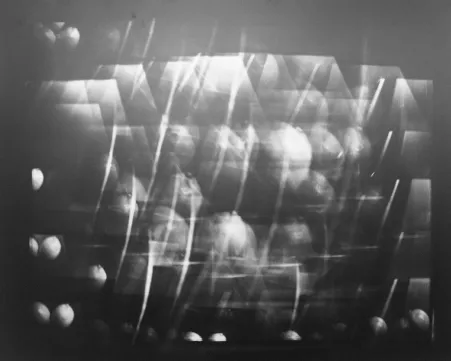

Photograph produced by Lemon camera (concave), negative 4×5 B/W. Photograph by Aïm Deüelle Lüski. Tel Aviv Museum Collection, 1977

The appearance of photography as the object of the gaze made a mockery of the simplistic opposition that had prevailed in the discourse on photography between the device and the subject wielding it, allowing for other possibilities to emerge that have been latent in photography from its inception, such as those intimated in Talbot’s own Pencil of Nature. The pencil (read “camera”) of nature could now be positioned differently—not as a device that wrote itself by itself, nor even as one wielded by the author who used it to produce pictures of other people. Rather, the pencil of nature could be seen as an inscribing machine that transforms the encounter that comes into being around it, through it and by means of its mediation, into a special form of encounter between participants where none of them possesses a sovereign status. In this encounter, in a structured fashion and despite the threat of disruption, the pencil of nature, for the most part, produces a visual protocol immune to the complete domination of any one of the participants in the encounter and to their possible claim for sovereignty. It is precisely this understanding that I would like to extrapolate from Talbot’s notion of the “pencil of nature” working in its own right. Human subjects, occupying different roles in the event of photography, do play one or another part in it, but the encounter between them is never entirely in the sole control of any one of them: no one is the sole signatory to the event of photography. In seeking thus to revise the notion of photography, it is clear that an ontological investigation of photography cannot concern itself with the technology of the camera alone. Nor can it be restricted to an investigation of the “final” product created by the camera, that is to say, the photograph. In other words, an ontological description of photography has to suspend the simple syntax of the sentence divided into subject, verb, predicate and adjective—photographer photographs a photograph with a camera—which has organized the discussion of photography for so long and which has gravely circumscribed that which is to be deemed relevant to a discussion of photography.

Photograph produced by Lemon camera (convex), negative 4×5 B/W. Photograph by Aïm Deüelle Lüski. Tel Aviv Museum Collection, 1977

The ontology of photography that I seek to promote is, in fact, a political ontology—an ontology of the many, operating in public, in motion. It is an ontology bound to the manner in which human beings exist—look, talk, act—with one another and with objects. At the same time, these subjects appear as the referents of speech, of the gaze and of the actions of others. My intention here is not to lay out an ontology of the political per se. It is, rather, to delineate the political ontology of photography. By this I mean an ontology of a certain form of human being-with-others in which the camera or the photograph are implicated. Neither the camera nor the photograph are sufficient to allow us to answer the question, “What is photography,” but without describing them as part of the political ontology I am setting forth, it will be difficult for us to reach reasonable conclusions.

The Camera

The camera is a relatively small box designed to produce images from that which is visible through a lens positioned in its front. It goes almost without saying that until the invention of the digital camera equipped with a screen, we were unable fully to perceive evidence of this capacity while the camera was in use, not to mention when it was turned off. At best we could merely invest the camera with such a capacity. When we encounter the camera, it is enough for it to be raised, or to be angled in a certain position in order to signal that it is directed at us or at others. This positioning itself carves up space between the person standing in front of the camera and the one standing behind it. The raised camera poses the threat of observing us, but it also observes us without our necessarily being aware of it. The camera can always respond to the temptation of observing us and of inscribing that which other spectators pass over without photographing or without so much as registering at all. Admittedly, the camera usually serves an individual. But it is increasingly put to use in situations where it no longer stands alone but appears alongside other cameras, intersects them, acts upon them and is acted upon by them. What is at stake in this context is a physical intersection, if often also an imaginary one, which occurs in real time but may also occur after the fact in cases where we identify places and people in photographs whom we recognize to have been in the same space as ourselves, sometimes even at the same time, together with or alongside still more individuals wielding cameras.

The number of cameras in circulation in the world is growing ceaselessly while the number of people not exposed to their presence is steadily diminishing. Even if the distribution of cameras is not constant from one geographical area to another, and even if there are zones, like disaster zones for instance, where the subjects of disaster are sentenced to be photographed rather than to photograph themselves, the omnipresence of the camera is a growing potential. The increased number of cameras together with their increased potential presence all over enables the camera to operate, as it were, even when it is not physically present, by virtue of the doubt that exists with respect to its overt or covert presence, its capacities for inscription and surveillance. There are no accurate estimates concerning the density of the distribution of cameras in various sites nor concerning their effects when they are trained upon us or, conversely, concerning their influence when they are not in use. But it is easy to surmise that these influences are just as considerable in their effect as is the formal productive capacity of the camera, that is to say, the capacity to produce pictures. One of the most obvious of these effects is the camera’s ability to create a commotion in an environment merely by being there—the camera can draw certain happenings to itself as if with a magnet, or even bring them into being, while it can also distance events, d...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- Chapter One: What Is Photography?

- Chapter Two: Rethinking the Political

- Chapter Three: The Photograph as a Source of Civil Knowledge

- Chapter Four: Civil Uses of Photography

- Epilogue: The Right Not to Be a Perpetrator

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index