- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

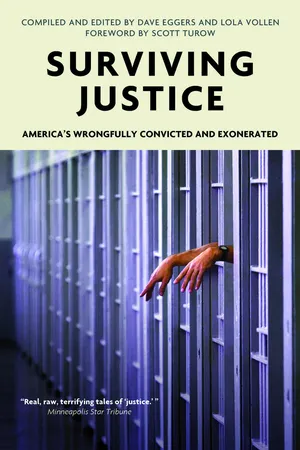

Surviving Justice: America's Wrongfully Convicted and Exonerated presents oral histories of thirteen people from all walks of life, who, through a combination of all-too-common factors-overzealous prosecutors, inept defense lawyers, coercive interrogation tactics, eyewitness misidentification-found themselves imprisoned for crimes they did not commit. The stories these exonerated men and women tell are spellbinding, heartbreaking, and ultimately inspiring.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Surviving Justice by Voice of Witness in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Civil Rights in Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

APPENDIX D:

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

I. EXCERPTS FROM THE THIRD EDITION OF CRIMINAL INTERROGATION AND CONFESSIONS

II. EXCERPT FROM A POLICE INTERROGATION OF THE VICTIM IN PETER ROSE’S CASE

III. EXCERPT FROM THE MASSACHUSETTS EXONEREE COMPENSATION BILL

IV. STATE-BY-STATE COMPENSATION LAWS

V. EXCERPT FROM ACHIM JOSEF MARINO’S 1998 CONFESSION LETTER

VI. RECOMMENDED REFORMS

I. EXCERPTS FROM THE THIRD EDITION OF CRIMINAL INTERROGATION AND CONFESSIONS

Written by Fred E. Inbau, John E. Reid, and Joseph P. Buckley, this seminal work has been used since the mid-1960s to train police officers and investigators to conduct effective interrogations. The manual, presented here in its 1986 edition, contains extensive instruction on the employment of psychological tactics and deception for interrogations of both suspects and victims.

[FROM THE INTRODUCTION]

… There is a gross misconception, generated and perpetuated by fiction writers, movies, and TV, that if criminal investigators carefully examine a crime scene, they will almost always find a clue that will lead them to the offender; and that, furthermore, once the criminal is located, he will readily confess or otherwise reveal guilt, as by attempting to escape. This, however, is pure fiction. As a matter of fact, the art and science of criminal investigation have not developed to a point where the search for and the examination of physical evidence will always, or even in most cases, reveal a clue to the identity of the perpetrator or provide the necessary legal proof of guilt. In criminal investigations, even the most efficient type, there are many, many instances where physical clues are entirely absent, and the only approach to a possible solution of the crime is the interrogation of the criminal suspect himself, as well as of others who may possess significant information. Moreover, in most instances, these interrogations, particularly of the suspect, most be conducted under conditions of privacy and for a reasonable period of time. They also frequently require the use of psychological tactics and techniques that could well be classified as “unethical,” if we are to evaluate them in terms of ordinary, everyday social behavior.

To protect ourselves from being misunderstood, we want to make it unmistakably clear that we are unalterably opposed to the so-called “third degree,” even on suspects whose guilt seems absolutely certain and who remain steadfast in their denials. Moreover, we are opposed to the use of any interrogation tactic or technique that is apt to make an innocent person confess. We are opposed, therefore, to the use of force, threats of force, or promises of leniency—any one of which might well induce an innocent person to confess. We do approve, however, of such psychological tactics and techniques as trickery and deceit that are not only helpful but frequently indispensable in order to secure incriminating information form the guilty, or to obtain investigative leads from otherwise uncooperative witnesses or informants…

… In Dealing with Criminal Offenders, and Consequently Also with Criminal Suspects Who May Actually Be Innocent, the Interrogator Must of Necessity Employ Less Refined Methods Than Are Considered Appropriate for the Transaction of Ordinary, Everyday Affairs by and between Law-Abiding Citizens…

… From the criminal’s point of view, any interrogation is unappealing and undesirable. To him it may be a “dirty trick” to encourage him to confess, for surely it is not being done for his benefit. Consequently, any interrogation might be labeled as deceitful or unethical, unless the suspect is first advised of its real purpose.

Of necessity, therefore, interrogators must deal with criminal suspects on a somewhat lower moral plane than that upon which ethical, law-abiding citizens are expected to conduct their everyday business affairs. That plane, in the interest of innocent suspects, need only be subject to the following restriction: Although both “fair” and “unfair” interrogation practices are permissible, nothing shall be done or said to the suspect that will be apt to make an innocent person confess.

There are other ways to guard against abuses by criminal interrogators short of taking the privilege away from them or by establishing unrealistic, unwarranted rules that render their task almost totally ineffective. Moreover, we could no more afford to do that than we could stand the effects of a law requiring automobile manufacturers to place governors on all cars so that, in order to make the highways safer, no one could go faster than 20 miles an hour.

[FROM CHAPTER ONE]

… Remember that when circumstantial evidence points toward a particular person, that person is usually the one who committed the offense. This may become difficult for some investigators and interrogators to appreciate when circumstantial evidence points to someone they consider highly unlikely to be the type of person who would commit such an offense, for example, a clergyman who is circumstantially implicated in a sexually-motivated murder. By reason of his exalted position, he may be interrogated only casually or perhaps not at all, and yet it is an established fact that some clergymen do commit such offenses.

[FROM CHAPTER FOUR]

…Recognize that in everyone there is some good, however slight it may be. The interrogator should seek to determine at the outset what desirable traits and qualities maybe possessed by the particular suspect. Thereafter, the interrogator can capitalize on those characteristics in the efforts toward a successful interrogation. The following example may seem to be an implausible one, but it actually happened during an ultimately successful interrogation of the perpetrator of a brutal crime. Reference was made to the kind treatment he had rendered his pet cat! The suspect was told that if he himself had been treated similarly by fellow humans, he would not have developed the attitude that led to his present difficulty. This proved to be very helpful in eliciting his confession.

[FROM CHAPTER FIVE]

Evaluation of Verbal and Nonverbal Responses

VERBAL RESPONSES

The period of time within which a verbal response is made to a probing question may be the first indication of truth or deception. An immediate response is a sign of truthfulness; a delay in answering indicates the possibility that the answer may be deceptive. This analysis is based upon the theory that a simple, direct, and unambiguous question does not require much deliberation before an answer is given. A delayed response, however, usually reflects an attempt to contrive a false answer. Another significant factor is whether or not the suspect answers the question directly. An answer such as “Who me?” or “I was home all day” or “I don’t own a gun” are not responsive answers to the direct question concerning the crime itself. They are evasive answers and typically are deceptive. The same is true of a suspect’s attempt to deviate from the subject matter altogether by injecting a comment that is unrelated to the objective of the question.

Also indicative of deception is suspect’s repetition of the interrogator’s question or a request that the interrogator repeat it or clarify it. For example, the suspect may say, in regard to an inquiry of his whereabouts on the day prior to the crime, “Do you mean yesterday, sir?,” or in an arson case, he may respond to a comparable question by asking “Do you mean did I start the fire?” even though he had just been asked a question only as to his whereabouts at the time of the fire. What this signifies is that the suspect is stalling for time in order to formulate what he thinks will be the most defensible response.

A suspect who hesitates in answering a question by saying “Let me see now,” prior to saying “no” is seeking to achieve two objectives: 1) to borrow time to deliberate on how to lie effectively or to remember previous statements, and 2) to camouflage true guilty reactions with the expression of a pretended serious thought.

The truthful suspect does not have to ponder over an answer. He really has only one answer, and it will be substantially the same, regardless of any repetition of the inquiry. Truthful suspects are not required to depend on a good memory, whereas liars are vulnerable and must be particularly careful to avoid making conflicting statements…

… Any suspect who is overly polite, even to the point of repeatedly calling the interrogator “sir” may be attempting to flatter the interrogator to gain his confidence. The suspect who, after being accused, says “No offense to you, sir, but I didn’t do it,” “I know you are just doing your job,” or “I understand what you are saying” is evidencing his lying about the matter under investigation. A truthful suspect has no need to make such apologetic statements, or even to explain that he understands the interrogator’s accusatory statements. To the contrary, the truthful suspect may very well react aggressively with a direct denial or by using strong language indicating anger over the implied accusation…

NONVERBAL RESPONSES

…Generally speaking, a suspect who does not make direct eye contact is probably being untruthful. However, some consideration should be given to the possibility of an eye disability, inferiority complex, or emotional instability, any of which may account for the avoidance of eye contact. Also, some cultural or religious customs consider it disrespectful for a person to look directly at an “authority figure.” Background information on the suspect, of course, may alert the interrogator regarding these or similar nondeceptive causes of a lack of eye contact…

EMOTIONAL CONDITION

In addition to precautions regarding the behavior symptoms of suspects, where doubt arises as to the validity of a crime reported by the purported victim, it is imperative to consider that the traumatic experience of the crime itself may produce reactions of nervousness or instability, which might be misinterpreted as indications of falsity. For example, a normally nervous-type victim who has just been robbed at gunpoint may be honestly confused or disoriented by the experience, and consequently may seem to be untruthful about the report of the incident. Or, a wife whose husband has been shot to death in her presence may have been so shocked by what she observed that her version of the incident soon thereafter may seem untruthful, when in fact she truthfully reported what occurred.

Another example of how misleading behavior symptoms may surface is one in which a male friend of a female murder victim was interrogated about her death. He displayed a number of symptoms, according to his initial interrogators. It was reported that he could not look them “straight in the eye,” that he sighed a lot, that he h...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Christopher Ochoa: My Life Is a Broken Puzzle

- Juan Melendez: My Mama Didn’t Raise No Killers

- Gary Gauger: I Stepped Into a Dream

- James Newsome: I Am the Expert

- Calvin Willis: Thank God for DNA

- John Stoll: If a Five-Year-Old Did It, You Did It

- Beverly Monroe: Now I Question Everything

- Michael Evans and Paul Terry: Sheep Among Wolves

- David Pope: Flowers in Your Hair

- Joseph Amrine: I’m a Dead Man Walking

- Peter Rose: Family Man

- Kevin Green: Bad Things Happen to Good People

- Exoneree Roundtable: People Don’t Know How Lucky They Are to Have Their Liberty

- Notes

- A Note about Methodology

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Causes of Wrongful Conviction

- Appendix B: The Prison Experience

- Appendix C: Life After Exoneration

- Appendix D: Supplementary Material

- Glossary

- About the Editors