- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the late 1960s the world was faced with impending disaster: the height of the Cold War, the end of oil, and the decline of great cities throughout the world. Out of this crisis came a new generation of thinkers, designers and engineers who hoped to build a better future, influenced by visions of geodesic domes, walking cities, and a meaningful connection with nature.

In this brilliant work of cultural history, architect Douglas Murphy traces the lost archeology of the present-day through the works of thinkers and designers such as Buckminster Fuller, the ecological pioneer Stewart Brand, the Archigram architects who envisioned the Plug-In City in the '60s, as well as co-operatives in Vienna, communes in the Californian desert, and protesters on the streets of Paris. In this mind-bending account of the last avant garde, we see not just the source of our current problems but also some powerful alternative futures.

In this brilliant work of cultural history, architect Douglas Murphy traces the lost archeology of the present-day through the works of thinkers and designers such as Buckminster Fuller, the ecological pioneer Stewart Brand, the Archigram architects who envisioned the Plug-In City in the '60s, as well as co-operatives in Vienna, communes in the Californian desert, and protesters on the streets of Paris. In this mind-bending account of the last avant garde, we see not just the source of our current problems but also some powerful alternative futures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Last Futures by Douglas Murphy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Museum of the Future

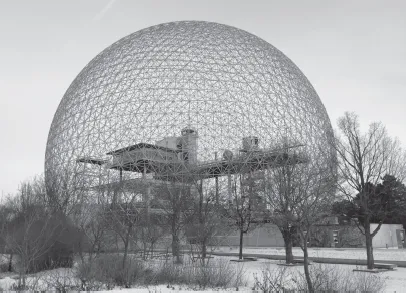

A visitor stepping out of Jean-Drapeau metro station in Montreal, Canada, is confronted with one of the oddest sights in all of architecture. Through the branches of the trees in this island park rises a strange silvery object. It is transparent, dissolving against the sky, a fuzzy haze that hardens towards its perfectly circular profile. If the visitor walks towards this odd vision, the beautiful and delicate lattice of its construction is revealed, along with the platforms and buildings within its spherical shell. A closer look shows that this filigree dome is welded together from innumerable short steel bars, as plain as scaffolding poles. Surrounded by greenery in summer and encrusted with icicles in the winter, the dome seems to melt into the sky, a huge object with almost no presence.

Approaching the dome along a pathway bordered by shallow ponds, the visitor will find that there is a small gap at the very bottom of the dome through which they can enter, and in passing through the threshold, a remarkable thing happens. Although the external world remains completely visible, all of a sudden the dome seems to vanish, its boundaries disappearing as the visitor moves inward. At the same time, the entire sky becomes marked with the grid of fine elements, in every direction; the triangles and hexagons of the structure seem as far away as the stars, ethereally etched against the sky above. The visitor feels as though they are both inside and outside at the same time, and that there is the most featherweight of protective boundaries around them at an almost indeterminate distance.

The geodesic dome of Buckminster Fuller’s USA Pavilion

This remarkable structure was once the USA Pavilion at Expo 67, one of the most iconic works of Richard Buckminster Fuller, the Cold War world’s most visionary designer.

Expo 67 was one of the most popular world exhibitions in the entire 150-year history of the cultural form. Awarded to Quebec in the early 1960s by the Bureau Internationale des Expositions, in part to mark the Canadian Centennial, over fifty nations took part and many millions of people passed through the park in the six months that it was open. It was situated on two artificially constructed islands in the St Lawrence River and linked to the rest of the city by new metro lines, bridges and a monorail. It involved the construction of hundreds of buildings, gardens and amusements, most of them temporary, some permanent, and some that were among the most important works of architecture of the 1960s.

It’s easy to forget now that world’s fairs were once highly significant events, pageants of progress, displays of industrial, technical and cultural power. Stranger still, they were entertaining, the sort of event where half a million people could pass through in a single day, with families travelling across countries, even from around the world, just to attend. Odd relics from an age where material culture was still the scene of the greatest achievements of progress and development, where new technology was large, visible and worth travelling to see, expos were a cross between amusement parks, political rallies and museums – museums of the near future.

The history of world’s fairs is inextricably tied into the history of global capitalism. Distant relatives of the old trade fairs that occurred throughout pre-industrial history, world’s fairs appeared almost fully formed with the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. This was the very first event in the world with a self-proclaimed global scope, inviting the nations of the world to come together and celebrate the new cultures of industrial production. Conceived in a genuine spirit of optimistic fraternity, but also as a spectacular patriotic event designed to help alleviate the social pressures that had led to revolutions all over the world in preceding years, it attempted to show that all people had a stake in the new world of capitalism and global trade.

It was also in the less noble interests of the UK to host the Great Exhibition as a demonstration of their might, given that at this point they still dominated the global economy, indeed were at the very zenith of their power. But there was also a chance for the USA and other countries to demonstrate their own achievements, which in many ways were beginning to threaten British supremacy. Within the exhibition the workings of industrial capitalism were put on public display. Arranged as a series of exhibits divided thematically and geographically, the millions of visitors who passed through encountered displays of raw materials, machinery and industrial equipment, and a bewildering range of products and manufactures. From furniture to textiles, from sculpture to the brand new media technology of photography, the Great Exhibition was a comprehensive introduction to the modern capitalist world.

The success of the Great Exhibition led to reiterations of the event in New York in 1853, Paris in 1855 and London again in 1862, before expositions spread across the world over the next fifty years. Early on, a pattern was established regarding the conventions of an expo, a pattern that involved massive, overwhelming collections of industrial machinery, raw materials, products, design, craftwork and fine art. Each World’s Fair was intended to display the achievements of industrial capitalism and give prominence to the power of global trade. Thus the nineteenth-century crowds who attended these events were educated in the world of commodities and exchange, as every conceivable object (including human beings) was on show, subject to the same regime of examination and economic comparison.

Fairs were dreamlike events, in many cases the visitors’ first experience of the fantastic qualities of capitalism, its aspirations and its tendency to abstract objects, processes and labour into an intangible realm. Furthermore, over the first half century, as the expositions became larger, they reflected growing waves of nationalism. In the process they became ‘safe’ spaces, akin to the Olympic Games, in which national tensions could be worked out visually and spatially, and where different ideologies would compete to stake their claim to offer the best future for humanity.

Architecture was absolutely integral to world’s fairs from the very beginning. From the fragile sublime of the Crystal Palace in 1851, the resounding entry of industrial engineering into an architectural world that was groaning under the weight of academic traditions, a pattern was set up of gigantic iron and glass palaces, vast single internal rooms filled with exhibits, veritable cornucopias of objects. This format – the giant hall stuffed with displays – reached its apotheosis with the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris, where the Eiffel Tower and Galerie des Machines created technical achievements in industrial architecture that remained unsurpassed for another forty years afterwards.

By the start of the twentieth century, expositions became so large that they spread across a selection of pavilions, each one assigned to a country or industrial corporation. This had the effect of multiplying the different voices expressed through architecture and allowed for the statements to become more complete. For example, Le Corbusier’s Esprit Nouveau pavilion in Paris’s 1925 L’Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes displayed his polemical proposals for high-rise living in Paris. The Plan Voisin was one of the most infamous architectural proposals ever made, with its depiction of a series of gigantic tower blocks smashed through the centre of Paris, for better or worse one of the most influential urban visions of all time.

At the same exposition, Konstantin Melnikov built the Soviet pavilion, a bold timber structure arranged across a diagonal axis, which today is one of the best known works of Russian constructivism, eulogised for its expression of the dynamic and hopeful energy of the early Soviet Union before Stalinism. The 1929 exhibition in Barcelona saw the construction of Mies van der Rohe’s German Pavilion, a deliciously refined series of polished steel columns and walls made of waxy travertine, demonstrating his vision of a luxury avant-garde – austere, technocratic, universal, yet classically minded – which would eventually evolve into the American post-war corporate style. At the 1937 Paris expo, Le Corbusier’s Pavillon des Temps Nouveaux casually introduced a technologically advanced steel-framed aesthetic that would go on to become incredibly influential for following generations, but this achievement was completely overwhelmed by the Soviet and German pavilions, both totalitarian, both classical, both headbangingly regressive.

The last expo before World War II, the New York World’s Fair in 1939, marked the transition from displays of industrial and cultural achievement to loud proclamations of the direction the future would take. Entitled ‘Dawn of a New Day’, it featured Futurama, an immersive exhibit created by titans of American industry General Motors, where visitors endured massive queues to be taken on a kind of futuristic ghost train. Inside, they sat in cars and were carried through a model environment depicting a near-future America of superfast highways, industrialised agriculture and bucolic super-suburbs. Today, Futurama appears something like a cross between Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and a fairly quotidian depiction of the skyscrapers and motorways that would later become so utterly familiar. It offered a corporate future based entirely around the motor car, with a germinal splash of the aesthetics of the atomic age. For the American visitors of the time, still smarting from the Great Depression and aware of – if not yet involved in – WWII, it presented an attractive image of the American future.

The primary architectural vision of the New York fair was a variation on the moderne style: streamlined and industrial but not too avant-garde. Its defining images were the Trylon and Perisphere, which were an obelisk and globe, white, near featureless and poised in such a way that they made for fantastic photographs, icons of their time. The Perisphere contained an exhibit, Democracity, which was another immersive vision of the future, conceived by Edward Bernays, nephew of Sigmund Freud and ‘father’ of public relations. Again, behind this gently optimistic view of the future was the power of the American corporations, who were subtly but aggressively attempting to stake a claim on the hearts and minds of the public as the politics of the New Deal threatened to sideline them from power.

It was not until thirteen years after WWII that there was another official world’s exhibition, Expo 58 in Brussels. At this point, one of the conceptual problems that would beset futuristic architecture over the second half of the twentieth century was already becoming apparent: in a world of atomic manipulation, of increasingly miniaturised electronic technologies, how best to display these new forms of technology in a spatial setting? This first post-war expo offered one the most blindingly obvious attempts to work this problem out. The Atomium, built for Expo 58 and still standing today, rises over 100 meters above Brussels and is a literal, inhabitable representation of an iron molecule. Nine large spheres – the atoms – are linked by structures representing the atomic bonds, which hold lifts and elevators that carry visitors to a viewing platform on the top floor.

A more successful attempt to deal with the new world of mass consumption and multimedia once again came from the studio of Le Corbusier. The Philips Pavilion, built for the electronics manufacturer, was almost completely unlike any other building in Le Corbusier’s oeuvre. This is due to it being largely the work of Iannis Xenakis, a Greek engineer working for Le Corbusier who, after an acrimonious split with the master relating to credit for the pavilion’s authorship, went on to become a renowned composer of experimental and stochastic music. For the pavilion, Le Corbusier (occupied somewhat with the building of the city of Chandigarh in India) sketched out a floor-plan that was a vague diagram of a stomach with two narrow entrances at either end. On top of this Xenakis set a series of hyperbolic paraboloids, saddle-shaped surfaces that curve in two directions, meeting at the edges to create a tent-like enclosure, which were realised as pre-fabricated concrete panels held in place partially by cables tied across the ruled surface.

Inside the Philips Pavilion, hundreds of loudspeakers and projectors were embedded into the walls for the purposes of displaying Poème électronique, a multimedia display featuring electroacoustic music by Edgar Varèse and a short film by Le Corbusier. Visitors were brought into the darkened hall before music and images emanated from all directions. Varèse’s composition is a near-collage of synthesised and recorded music, with samples of industrial, musical and vocal noises and a variety of abstract and more tonal electronic sounds. It is mostly sparse in texture, with long silences, although there are moments of high intensity. The accompanying film was also a collage, with images ranging from European avant-garde staples such as tribal masks and ancient sculpture to animals, roads, cities (including several buildings by Le Corbusier) and images of nuclear explosions and starving concentration camp inmates. The Philips Pavilion was a deeply modernist multimedia experience, a corporate-sponsored experience whose every aspect was avant-garde. Although immersive multimedia technology would become ever more prevalent in expo culture, it would never again be so uncompromisingly experimental.

The New York World’s Fair of 1964 was dampened by conflicts within the Bureau Internationale des Expositions (BIE), meaning that few international exhibitors took part. Instead it offered a vivid portrait of the United States’ self-image at the height of its own world power. The theme of ‘Peace Through Understanding’ paid the traditional lip-service to fraternity while also making a blatant point about the Cold War. Meanwhile the dedication ‘Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe’ was obviously born of the space programme, developments in cosmology and the race to the moon. The fair was held on the same land, Flushing Meadows Park, as the 1939 fair had been, and Robert Moses the arch-planner, who had reclaimed the land for the earlier expo, was given the job of delivering the later one. General Motors reprised their Futurama exhibit from a quarter century before, but this time the future they presented was less about life in an ordinary city and far more focused on frontier conditions: moon bases, orbital colonies, Antarctic research centres, underwater hotels, jungle cities and so on. Futurama II was dominated by a blasé feeling of American capitalism’s technological dominance over adversarial natural conditions, seeking out resources and new frontiers wherever they could be found. Elsewhere at the 1964 fair, and perhaps most significantly, IBM laid on a spectacle of new digital technologies that was the very first encounter with a computer for many of the millions who passed through.

Of all the world’s fairs, Expo 67 had one of the strongest claims on the future as a conceptual vision, but it also marked the point at which a backlash against the uncritical celebration of technology began to make itself felt in establishment consciousness. It occurred at the point in the twentieth century when accelerating progress was at its strongest, but this spirit was met with an emerging wave of self-criticism and social experiment that had perhaps not been seen before that century. The Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, the student revolts, the New Left and the counterculture were either already prominent or on the rise. The Apollo programme was nearing its successful attempt to land humans on the moon. Along with these major changes, Expo 67 was a point almost at the zenith of architecture’s power as a vehicle for dreams of new social and technical organisation, but also where a perceived irrelevance of architecture began, gradually, to become apparent.

The title of Expo 67, ‘Man and His World’ (Terre des Hommes), is taken from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the author of The Little Prince. It is the name of a 1939 book that contains a passage wherein the author looks out from an aeroplane at night and becomes startlingly aware of the fragility of human existence on the earth below. This awakened global consciousness was in tune with the growing public awareness of sciences such as ecology and cybernetics, as well as the recent expeditions into outer space that were so prominent in the public imagination.

The motif was carried through the entire expo with pavilions devoted to various sub-themes such as ‘Man the Explorer’, ‘Man the Creator’, ‘Man the Producer’ and so on. This unreconstructed notion of ‘man’, which might sound strange to contemporary ears, is particularly significant for two reasons: one, the expo was notable for the involvement of many recently decolonized African countries such as Algeria, Ghana, Kenya and others, who were attempting to use the prominence of the expo as an opportunity to solidify public acceptance of their arrival as independent nations. On the other hand, ‘man’ becomes a word that universalises humanity through a sense of cosmic distance, where divisions are indistinguishable and patterns of behaviour common to all. In both these cases the word ‘man’ takes on a conspicuousness for its stressing of a (not unproblematic) universality, a world beyond struggle and conflict. Indeed, the fact that visitors were given a ‘passport’ instead of a ticket emphasises the notion of the expo as a zone apart from the political problems of the world.

Architecturally, Expo 67 was an exciting prospect. Gone were the overt science fiction conceits of previous years, in favour of a number of variations of a more genuinely technical design language. By this point, the architectural language of modernism that was formed out of the European avant-garde between the wars was at its most popular, with brutalism – that heavy, expressive, formally exuberant method – at its historic peak. Developed out of a fusion of Le Corbusier’...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Museum of the Future

- Chapter 2: The City out of History

- Chapter 3: Megastructure Visions

- Chapter 4: Systems and Failures

- Chapter 5: Cybernetic Dreams

- Chapter 6: Reactions and Defeats

- Chapter 7: Apocalypse Then

- Chapter 8: Biospheres and the End

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Illustration Credits

- Index