- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

John Berger, one of the world's most celebrated storytellers and writers on art, tells a personal history of art from the prehistoric paintings of the Chauvet caves to 21st century conceptual artists. Berger presents entirely new ways of thinking about artists both canonized and obscure, from Rembrandt to Henry Moore, Jackson Pollock to Picasso. Throughout, Berger maintains the essential connection between politics, art and the wider study of culture. The result is an illuminating walk through many centuries of visual culture, from one of the contemporary world's most incisive critical voices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Portraits by John Berger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

The Chauvet Cave Painters

(c. 30,000 years BC)

YOU, MARISA, WHO have painted so many creatures and turned over many stones and crouched for hours looking, perhaps you will follow me.

Today I went to the street market in a suburb south of Paris. You can buy everything there from boots to sea urchins. There’s a woman who sells the best paprika I know. There’s a fishmonger who shouts out to me whenever he has an unusual fish that he finds beautiful, because he thinks I may buy it in order to draw it. There’s a lean man with a beard who sells honey and wine. Recently he has taken to writing poetry, and he hands out photocopies of his poems to his regular clients, looking even more surprised than they do.

One of the poems he handed me this morning went like this:

Mais qui piqua ce triangle dans ma tête?

Ce triangle né du clair de lune

me traversa sans me toucher

avec des bruits de libellule

en pleine nuit dans le rocher.

Who put this triangle in my head?

This triangle born of moonlight

went through me without touching me

making the noise of a dragonfly

deep in the rock at night.

After I read it, I wanted to talk to you about the first painted animals. What I want to say is obvious, something which everybody who has looked at paleolithic cave paintings must feel, but which is never (or seldom) said clearly. Maybe the difficulty is one of vocabulary; maybe we have to find new references.

The beginnings of art are being continually pushed back in time. Sculpted rocks just discovered at Kununurra in Australia may date back seventy-five thousand years. The paintings of horses, rhinoceros, ibex, mammoths, lions, bears, bison, panthers, reindeer, aurochs, and an owl, found in 1994 in the Chauvet Cave in the French Ardèche, are probably fifteen thousand years older than those found in the Lascaux caves! The time separating us from these artists is at least twelve times longer than the time separating us from the pre-Socratic philosophers.

What makes their age astounding is the sensitivity of perception they reveal. The thrust of an animal’s neck or the set of its mouth or the energy of its haunches were observed and recreated with a nervousness and control comparable to what we find in the works of a Fra Lippo Lippi, a Velázquez, or a Brancusi. Apparently art did not begin clumsily. The eyes and hands of the first painters and engravers were as fine as any that came later. There was a grace from the start. This is the mystery, isn’t it?

The difference between then and now concerns not finesse but space: the space in which their images exist as images and were imagined. It is here – because the difference is so great – that we have to find a new way of talking.

There are fortunately superb photographs of the Chauvet paintings. The cave has been closed up and no public visits will be allowed. This is a correct decision, for like this, the paintings can be preserved. The animals on the rocks are back in the darkness from which they came and in which they resided for so long.

We have no word for this darkness. It is not night and it is not ignorance. From time to time we all cross this darkness, seeing everything: so much everything that we can distinguish nothing. You know it, Marisa, better than I. It’s the interior from which everything came.

ONE JULY EVENING this summer, I went up the highest field, high above the farm, to fetch Louis’s cows. During the haymaking season I often do this. By the time the last trailer has been unloaded in the barn, it’s getting late and Louis has to deliver the evening milk by a certain hour, and anyway we are tired, so, while he prepares the milking machine, I go to bring in the herd. I climbed the track that follows the stream that never dries up. The path was shady and the air was still hot, but not heavy. There were no horseflies as there had been the previous evening. The path runs like a tunnel under the branches of the trees, and in parts it was muddy. In the mud I left my footprints among the countless footprints of cows.

To the right the ground drops very steeply to the stream. Beech trees and mountain ash prevent it being dangerous; they would stop a beast if it fell there. On the left grow bushes and the odd elder tree. I was walking slowly, so I saw a tuft of reddish cow hair caught on the twigs of one of the bushes.

Before I could see them, I began to call. Like this, they might already be at the corner of the field to join me when I appeared. Everyone has their own way of speaking with cows. Louis talks to them as if they were the children he never had: sweetly or furiously, murmuring or swearing. I don’t know how I talk to them; but, by now, they know. They recognise the voice without seeing me.

Painting in Chauvet Cave, c. 30,000 BC

When I arrived they were waiting. I undid the electric wire and cried: Venez, mes belles, venez. Cows are compliant, yet they refuse to be hurried. Cows live slowly – five days to our one. When we beat them, it’s invariably out of impatience. Our own. Beaten, they look up with that long-suffering, which is a form (yes, they know it!) of impertinence, because it suggests, not five days, but five eons.

They ambled out of the field and took the path down. Every evening Delphine leads, and every evening Hirondelle is the last. Most of the others join the file in the same order, too. The regularity of this somehow suits their patience.

I pushed against the lame one’s rump to get her moving, and I felt her massive warmth, as I did every evening, coming up to my shoulder under my singlet. Allez, I told her, allez, Tulipe, keeping my hand on her haunch, which jutted out like the corner of a table.

In the mud their steps made almost no noise. Cows are very delicate on their feet: they place them like models turning on high-heeled shoes at the end of their to-and-fro. I’ve even had the idea of training a cow to walk on a tightrope. Across the stream, for instance!

The running sound of the stream was always part of our evening descent, and when it faded the cows heard the toothless spit of the water pouring into the trough by the stable where they would quench their thirst. A cow can drink about thirty litres in two minutes.

Meanwhile, that evening we were making our slow way down. We were passing the same trees. Each tree nudged the path in its own way. Charlotte stopped where there was a patch of green grass. I tapped her. She went on. It happened every evening. Across the valley I could see the already mown fields.

Hirondelle was letting her head dip with each step, as a duck does. I rested my arm on her neck, and suddenly I saw the evening as from a thousand years away:

Louis’s herd walking fastidiously down the path, the stream babbling beside us, the heat subsiding, the trees nudging us, the flies around their eyes, the valley and the pine trees on the far crest, the smell of piss as Delphine pissed, the buzzard hovering over the field called La Plaine Fin, the water pouring into the trough, me, the mud in the tunnel of trees, the immeasurable age of the mountain, suddenly everything there was indivisible, was one. Later each part would fall to pieces at its own rate. Now they were all compacted together. As compact as an acrobat on a tightrope.

‘Listening not to me but to the logos, it is wise to agree that all things are one,’ said Heraclitus, twenty-nine thousand years after the Chauvet paintings were made. Only if we remember this unity and the darkness we spoke of, can we find our way into the space of those first paintings.

Nothing is framed in them; more important, nothing meets. Because the animals run and are seen in profile (which is essentially the view of a poorly armed hunter seeking a target) they sometimes give the impression that they’re going to meet. But look more carefully: they cross without meeting.

Their space has absolutely nothing in common with that of a stage. When experts pretend that they can see here ‘the beginnings of perspective’, they are falling into a deep, anachronistic trap. Pictorial systems of perspective are architectural and urban – depending upon the window and the door. Nomadic ‘perspective’ is about coexistence, not about distance.

Deep in the cave, which meant deep in the earth, there was everything: wind, water, fire, faraway places, the dead, thunder, pain, paths, animals, light, the unborn … They were there in the rock to be called to. The famous imprints of life-size hands (when we look at them we say they are ours) – these hands are there, stencilled in ochre, to touch and mark the everything-present and the ultimate frontier of the space this presence inhabits.

The drawings came, one after another, sometimes to the same spot, with years or perhaps centuries between them, and the fingers of the drawing hand belonging to a different artist. All the drama that in later art becomes a scene painted on a surface with edges is compacted here into the apparition that has come through the rock to be seen. The limestone opens for it, lending it a bulge here, a hollow there, a deep scratch, an overhanging lip, a receding flank.

When an apparition came to an artist, it came almost invisibly, trailing a distant, unrecognisably vast sound, and he or she found it and traced where it nudged the surface, the facing surface, on which it would now stay visible even when it had withdrawn and gone back into the one.

Things happened that later millennia found it hard to understand. A head came without a body. Two heads arrived, one behind the other. A single hind leg chose its body, which already had four legs. Six antlers settled in a single skull.

It doesn’t matter what size we are when we nudge the surface: we may be gigantic or small – all that matters is how far we have come through the rock.

The drama of these first painted creatures is neither to the side nor to the front, but always behind, in the rock. From where they came. As we did, too …

2.

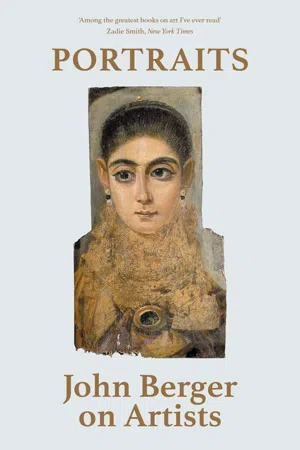

The Fayum Portrait Painters

(1st–3rd century)

THEY ARE THE earliest painted portraits that have survived; they were painted whilst the Gospels of the New Testament were being written. Why then do they strike us today as being so immediate? Why does their individuality feel like our own? Why is their look more contemporary than any look to be found in the rest of the two millennia of traditional European art which followed them? The Fayum portraits touch us, as if they had been painted last month. Why? This is the riddle.

The short answer might be that they were a hybrid, totally bastard art-form, and that this heterogeneity corresponds with something in our present situation. Yet to make this answer comprehensible we have to proceed slowly.

They are painted on wood – often linden – and some are painted on linen. In scale the faces are a little smaller than life. A number are painted in tempera; the medium used for the majority is encaustic, that is to say, colours mixed with beeswax, applied hot if the wax is pure, and cold if it has been emulsified.

Today we can still follow the painter’s brushstrokes or the marks of the blade he used for scraping on the pigment. The preliminary surface on which the portraits were done was dark. The Fayum painters worked from dark to light.

What no reproduction can show is how appetising the ancient pigment still is. The painters used four colours apart from gold: black, red, and two ochres. The flesh they painted with these pigments makes one think of the bread of life itself. The painters were Greek Egyptian. The Greeks had settled in Egypt since the conquest of Alexander the Great, four centuries earlier.

They are called the Fayum portraits because they were found at the end of the last century in the province of Fayum, a fertile land around a lake, a land called the Garden of Egypt, eighty kilometres west of the Nile, a little south of Memphis and Cairo. At that time a dealer claimed that portraits of the Ptolemies and Cleopatra had been found! Then the paintings were dismissed as fakes. In reality they are genuine portraits of a professional urban middle class – teachers, soldiers, athletes, Serapis priests, merchants, florists. Occasionally we know their names – Aline, Flavian, Isarous, Claudine …

They were found in necropolises, for they were painted to be attached to the mummy of the person portrayed, when he or she died. Probably they were painted from life (some must have been because of their uncanny vitality); others, following a sudden death, may have been done posthumously.

They served a double pictorial function: they were identity pictures – like passport photos – for the dead on their journey with Anubis, the god with the jackal’s head, to the kingdom of Osiris; secondly and briefly, they served as mementoes of the departed for the bereaved family. The embalming of the body took seventy days, and sometimes after this, the mummy would be kept in the house, leaning against a wall, a member of the family circle, before being finally placed in the necropolis.

Styli...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: The Company of the Past

- 1. The Chauvet Cave Painters (c. 30,000 years BC)

- 2. The Fayum Portrait Painters (1st–3rd century)

- 3. Piero della Francesca (c. 1415–92)

- 4. Antonello da Messina (c. 1430–79)

- 5. Andrea Mantegna (1430/1–1506)

- 6. Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450–1516)

- 7. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–69)

- 8. Giovanni Bellini (active about 1459, died 1516)

- 9. Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470–1528)

- 10. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- 11. Michelangelo (1475–1564)

- 12. Titian (?1485/90–1576)

- 13. Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8–1543)

- 14. Caravaggio (1571–1610)

- 15. Frans Hals (1582/3–1666)

- 16. Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

- 17. Rembrandt (1606–69)

- 18. Willem Drost (1633–1659)

- 19. Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

- 20. Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

- 21. Honoré Daumier (1808–79)

- 22. J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851)

- 23. Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Géricault (1791–1824)

- 24. Jean-François Millet (1814–75)

- 25. Gustave Courbet (1819–77)

- 26. Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

- 27. Ferdinand ‘Le Facteur’ Cheval (1836–1924)

- 28. Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

- 29. Claude Monet (1840–1926)

- 30. Vincent van Gogh (1853–90)

- 31. Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945)

- 32. Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- 33. Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

- 34. Fernand Léger (1881–1955)

- 35. Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967)

- 36. Henry Moore (1898–1986)

- 37. Peter Lazslo Peri (1899–1967)

- 38. Alberto Giacometti (1901–66)

- 39. Mark Rothko (1903–70)

- 40. Robert Medley (1905–94)

- 41. Frida Kahlo (1907–54)

- 42. Francis Bacon (1909–92)

- 43. Renato Guttuso (1911–87)

- 44. Jackson Pollock (1912–56)

- 45. Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner (1908–84)

- 46. Abidin Dino (1913–93)

- 47. Nicolas de Staël (1914–55)

- 48. Prunella Clough (1919–99)

- 49. Sven Blomberg (1920–2003)

- 50. Friso Ten Holt (1921–97)

- 51. Peter de Francia (1921–2012)

- 52. Francis Newton Souza (1924–2002)

- 53. Yvonne Barlow (1924–)

- 54. Ernst Neizvestny (1925–)

- 55. Leon Kossoff (1926–)

- 56. Anthony Fry (1927–)

- 57. Cy Twombly (1928–2011)

- 58. Frank Auerbach (1931–)

- 59. Vija Celmins (1938–)

- 60. Michael Quanne (1941–)

- 61. Maggi Hambling (1945–)

- 62. Liane Birnberg (1948–)

- 63. Peter Kennard (1949–)

- 64. Andres Serrano (1950–)

- 65. Juan Muñoz (1953–2001)

- 66. Rostia Kunovsky (1954–)

- 67. Jaume Plensa (1955–)

- 68. Cristina Iglesias (1956–)

- 69. Martin Noel (1956–2008)

- 70. Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–88)

- 71. Marisa Camino (1962–)

- 72. Christoph Hänsli (1963–)

- 73. Michael Broughton (1977–)

- 74. Randa Mdah (1983–)

- Acknowledgements

- Illustration Credits