eBook - ePub

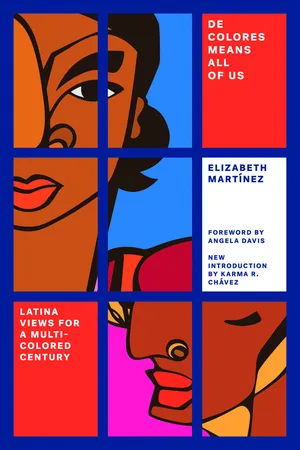

De Colores Means All of Us

Latina Views for a Multi-Colored Century

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Elizabeth Mart?nez's unique Chicana voice arises from over thirty years of experience in the movements for civil rights, women's liberation, and Latina/o empowerment. In De Colores Means All of Us, Mart?nez presents a radical Latina perspective on race, liberation, and identity. In these essays, Mart?nez describes the provocative ideas and new movements created by the rapidly expanding U.S. Latina/o community as it confronts intensified exploitation and racism. With sections on women's organizing, struggles for economic justice and immigrant rights, and the Latina/o youth movement, this book will appeal to readers and activists seeking to organize for the future and build new movements for social change. With a foreword from Angela Y. Davis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access De Colores Means All of Us by Elizabeth Sutherland Martînez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Civics & Citizenship. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

part one

SEEING MORE THAN

BLACK AND WHITE

Queremos ser libres

y la nueva forma

de ser libres

es serlo juntos.

We want to be free

and the new way

of being free

is to be free together.

—palabras zapatistas/EZLN

—from the Zapatista movement

—from the Zapatista movement

chapter one

A WORD ABOUT

THE GREAT TERMINOLOGY QUESTION

On one hand, there are real grounds for confusion. The term “Chicano” or “Chicana” eludes simple definition because it stands for a mix that is both racial and cultural. It refers to a people who are neither strictly Mexican nor strictly Yankee—as well as both. Go to Mexico and you will quickly realize that most people there do not see Chicanos as Mexican. You may even hear the term “brown gringo.” Live in the United States, and you will quickly discover that the dominant population doesn’t see Chicanos as real Americans.

Confusion, ignorance and impassioned controversy about terminology make it necessary, then, to begin this book with such basic questions as: what is a Chicana or Chicano? (And remember, Spanish is a gendered language, hence Chicana/Chicano.)

For starters, we combine at least three roots: indigenous (from pre-Columbian times), European (from the Spanish and Portuguese invasions) and African (from the many slaves brought to the Americas, including at least 200,000 to Mexico alone). A smattering of Chinese should be added, which goes back to the sixteenth century; Mexico City had a Chinatown by the mid-1500s, some historians say. Another mestizaje, or mixing, took place—this time with Native Americans of various nations, pueblos and tribes living in what is now the Southwest—when Spanish and Mexican colonizers moved north. Later our Chicano ancestors acquired yet another dimension through intermarriage with Anglos.

The question arises: is the term “Chicano” the same as “Mexican American” or “Mexican-American”? Yes, except in the sense of political self-definition. “Chicano/a” once implied lower-class status and was at times derogatory. During the 1960s and 1970s, in an era of strong pressure for progressive change, the term became an outcry of pride in one’s peoplehood and rejection of assimilation as one’s goal. Today the term “Chicano/a” refuses to go away, especially among youth, and you will still hear jokes like “A Chicano is a Mexican American who doesn’t want to have blue eyes” or “who doesn’t eat white bread” or whatever. (Some believe the word itself, by the way, comes from “Mexica”—pronounced “Meshica”—which was the early name for the Aztecs.)

People ask: are Chicanos different from Latinos?

At the risk of impassioned debate, let me say: we are one type of Latino. In the United States today, Latinos and Latinas include men and women whose background links them to some 20 countries, including Mexico. Many of us prefer “Latino” to “Hispanic,” which obliterates our indigenous and African heritage, and recognizes only the European, the colonizer. (Brazilians, of course, reject “Hispanic” strongly because their European heritage is Portuguese, not Spanish.) “Hispanic” also carries the disadvantage of being a term that did not emerge from the community itself but was imposed by the dominant society through its census bureau and other bureaucracies, during the Nixon administration of the 1970s.

Today most of the people who say “Hispanic” do so without realizing its racist implications, simply because they see and hear it everywhere. Some who insist on using the term point out that “Latino” is no better than “Hispanic” because it also implies Eurocentricity. Many of us ultimately prefer to call ourselves “La Raza” or simply “Raza,” meaning “The People,” which dates back many years in the community. (Again we find complications in actual usage: some feel that Raza refers to people of Mexican and perhaps also Central American origin, and doesn’t include Latinos from other areas.)

We are thus left with no all-embracing term acceptable to everyone. In the end, the most common, popular identification is by specific nationality: Puerto Rican, Mexican, Guatemalan, Colombian and so forth. But those of us who seek to build continental unity stubbornly cling to some broadly inclusive way of defining ourselves. In my own case, that means embracing both “Chicana” and “Latina.”

At the heart of the terminology debate is the historical experience of Raza. Invasion, military occupation and racist control mechanisms all influence the evolution of words describing people who have lived through such trauma. The collective memory of every Latino people in cludes direct or indirect (neo-)colonialism, primarily by Spain or Portugal and later by the United States.

Among Latinos, Mexicans in what we now call the Southwest have experienced U.S. colonialism the longest and most directly, with Puerto Ricans not far behind. Almost one-third of today’s United States was the home of Mexicans as early as the 1500s, until Anglos seized it militarily in 1848 and treated its population as conquered subjects. (The Mexicans, of course, themselves occupied lands that had been seized from Native Americans.) Such oppression totally violated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the 1846–48 war and promised respect for the civil and property rights of Mexicans remaining in the Southwest. The imposition of U.S. rule involved taking over millions of acres of Mexican-held land by trickery and violence. Colonization also brought the imposition of Anglo values and institutions at the expense of Mexican culture, including language. Hundreds of Mexicans were lynched as a form of control.

In the early 1900s, while colonization continued, the original Mexican population of the Southwest was greatly increased by an immigration that continues today. This combination of centuries-old roots with relatively recent ones gives the Mexican-American people a rich and varied cultural heritage. It means that Chicanos are not by origin an immigrant people in the United States (except compared with the Native Americans); their roots go back four centuries. Yet they also include immigrants. Too many Americans see only the recent arrivals, remaining blind to those earlier roots and what they signify.

We cannot understand all that history simply in terms of victimization: popular resistance is its other face. Raza resistance, which took the form of organized armed struggle in the Southwest during the last century, continues today in many forms. These include rejecting the colonized mentality, that pernicious, destructive process of internalizing a belief in the master’s superiority and our inferiority.

The intensity of the terminology debate comes as no surprise, then, for it echoes people’s struggles for non-racist—indeed, anti-racist—ways of defining themselves. Identity continues to be a major concern of youth in particular, with reason. But an obsession with self-definition can become a trap if that is all we think about, all we debate. If liberatory terminology becomes an end in itself and our only end, it ceases to be a tool of liberation. Terms can be useful, even vital tools, but the house of La Raza that is waiting to be built needs many kinds.

chapter two

SEEING MORE THAN

BLACK AND WHITE

Introduction

Such alliances require a knowledge and wisdom that we have yet to acquire. Today it remains painful to see how divide-and-conquer strategies succeed among people of color. It is painful to see how prejudice, resentment, petty competitiveness and sheer ignorance fester. It is positively pitiful to see how we echo Anglo stereotypes about each other.

These divisions indicate that we urgently need some fresh and fearless thinking about racism, which might begin with analyzing the strong tendency to frame U.S. racial issues in strictly Black-white terms. Such terms make little sense when a 1996 U.S. Census report says that 33 percent of our population will be Asian/Pacific Island-American, Latino, Native American/Indigenous (which includes Hawaiian) and Arab-American by the year 2050–in other words, neither white nor Black. (Steven A. Holmes, “Census Sees a Profound Ethnic Shift in U.S.,” New York Times, March 14, 1996.) Also, we find an increasing number of mixed people who incorporate two, three or more “races.”

The racial and ethnic landscape has changed too much in recent years to view it with the same eyes as before. We are looking at a multi-dimensional reality in which race, ethnicity, nationality, culture and immigrant status come together with breathtakingly new results. We are also seeing global changes that have a massive impact on our domestic situation, especially the economy and labor force. For a group of Korean restaurant entrepreneurs to hire Mexican cooks to prepare Chinese dishes for mainly African-American customers, as happened in Houston, Texas, has ceased to be unusual.

The ever-changing demographic landscape compels those struggling against racism and for a transformed, non-capitalist society to resolve several strategic questions. Among them: doesn’t the exclusively Black-white framework discourage the perception of common interests among people of color and thus sustain White Supremacy? Doesn’t the view that only African Americans face serious institutionalized racism isolate them from potential allies? Doesn’t the Black-white model encourage people of color to spend too much energy understanding our lives in relation to whiteness, obsessing about what white society will think and do?

That tendency is inevitable in some ways: the locus of power over our lives has long been white (although big shifts have recently taken place in the color of capital, as we see in Japan, Singapore and elsewhere). The oppressed have always survived by becoming experts on the oppressor’s ways. But that can become a prison of sorts, a trap of compulsive vigilance. Let us liberate ourselves, then, from the tunnel vision of whiteness and behold the many colors around us! Let us summon the courage to reject outdated ideas and stretch our imaginations into the next century.

For a Latina to urge recognizing a variety of racist models is not, and should not be, yet another round in the Oppression Olympics. We don’t need more competition among different social groups for the gold medal of “Most Oppressed.” We don’t need more comparisons of suffering between women and Blacks, the disabled and the gay, Latino teenagers and white seniors, or whatever. Pursuing some hierarchy of oppression leads us down dead-end streets where we will never find the linkage between different oppressions and how to overcome them. To criticize the exclusively Black-white framework, then, is not some resentful demand by other people of color for equal sympathy, equal funding, equal clout, equal patronage or other questionable crumbs. Above all, it is not a devious way of minimizing the centrality of the African-American experience in any analysis of racism.

The goal in re-examining the Black-white framework is to find an effective strategy for vanquishing an evil that has expanded rather than diminished. Racism has expanded partly as a result of the worldwide economic recession that followed the end of the post-war boom in the early 1970s, with the resulting capitalist restructuring and changes in the international division of labor. Those developments generated feelings of insecurity and a search for scapegoats. In the United States racism has also escalated as whites increasingly fear becoming a weakened, minority population. The stage is set for decades of ever more vicious divide-and-conquer tactics.

What has been the response from people of color to this ugly White Supremacist agenda? Instead of uniting, based on common experience and needs, we have often closed our doors in a defensive, isolationist mode, each community on its own. A fire of fear and distrust begins to crackle, threatening to consume us all. Building solidarity among people of color is more necessary than ever—but the exclusively Black-white definition of racism makes such solidarity more difficult than ever.

We urgently need twenty-first-century thinking that will move us beyond the Black-white framework without negating its historical role in the construction of U.S. racism. We need a better understanding of how racism developed both similarly and differently for various peoples, according to whether they experienced genocide, enslavement, colonization or some other structure of oppression. At stake is the building of a united anti-racist force strong enough to resist White Supremacist strategies of divide-and-conquer and move forward toward social justice for all.

My call to rethink the prevailing framework of U.S. racism is being sounded by others today: academics, liberal foundation administrators and activist-intellectuals. But new thinking seems to proceed in fits and starts, or tokenistically, as if dogged by a fear of stepping on others’ toes or being seen as a traitor to one’s own community. Even progressive scholars of color often fail to go beyond perfunctorily saluting a vague multiculturalism.

Serious opposition to developing a new model also exists. Academics of color scrambling for funds will support only one flavor of Ethnic Studies and to hell with the others. Politicians of one color will cultivate distrust of others as a tactic to gain popularity in their own communities. When we hear, for example, of Black/Latino friction in the electoral arena, we should look below the surface for the reasons. In Los Angeles and New York, politicians out to score patronage and payola have played the narrow nationalist game, whipping up economic anxiety and provoking a resentment that sets communities against each other. White folks have no monopoly on such tactics.

We also find opposition from ordinary people with no self-interest in resisting a new model. African Americans have reason to be uneasy about where they, as a people, will find themselves politically, economically and socially with the rapid numerical growth of other folk of color. The issue is not just possible job loss, a real question that does need to be faced honestly. There is also a feeling that after centuries of fighting for simple recognition as human beings, Blacks will be shoved to the back of history again (like the back of the bus). Whether these fears are real or not, uneasiness exists and can lead to resentment when there’s talk about a new model of race relations. So let me repeat: in speaking here of the need to move beyond the bipolar concept, the goal is to clear the way for stronger unity against White Supremacy. The goal is to identify our commonalities of experience and needs so we can build alliances.

The commonalities begin with history, which reveals that again and again peoples of color have had one experience in common: European colonization and/or neo-colonialism with its accompanying exploitation. This is true for all indigenous peoples, including Hawaiians. It is true for all Latino peoples, who were invaded and ruled by Spain or Portugal. It is true for people in Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands, where European powers became the colonizers. People of color were victimized by colonialism not only externally but also through internalized racism—the “colonized mentality.”

Flowing from this shared history are our contemporary commonalities. On the poverty scale, African Americans and Native Americans have always been at the bottom, with Latinos nearby. In 1997 the U.S. Census found that Latinos have the highest poverty rate, 24 percent. Segregation may have been legally abolished in the 1960s, but now the United States is rapidly moving toward resegregation as a result of whites moving to the suburbs. This leaves people of color—especially Blacks and Latinos—with inner cities that lack an adequate tax base and thus have inadequate schools. Not surprisingly, Blacks ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- About “De Colores”

- Contents

- Introduction to the 2017 Edition

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: A Call for Rainbow Warriors

- Part One: Seeing More Than Black and White

- Part Two: No Hay Fronteras: The Attack On Immigrant Rights

- Part Three: Fighting for Economic and Environmental Justice

- Part Four: Racism and the Attack on Multiculturalism

- Part Five: Woman Talk: No Taco Belles Here

- Part Six: La Lucha Continua: Youth In The Lead

- Afterword

- Index