- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Transformations in Cuban art, literature and culture in the post-Fidel era

Cuba has been in a state of massive transformation over the past decade, with its historic resumption of diplomatic relations with the United States only the latest development. While the political leadership has changed direction, other forces have taken hold. The environment is under threat, and the culture feels the strain of new forms of consumption.

Planet/Cuba examines how art and literature have responded to a new moment, one both more globalized and less exceptional; more concerned with local quotidian worries than international alliances; more threatened by the depredations of planetary capitalism and climate change than by the vagaries of the nation's government. Rachel Price examines a fascinating array of artists and writers who are tracing a new socio-cultural map of the island.

Cuba has been in a state of massive transformation over the past decade, with its historic resumption of diplomatic relations with the United States only the latest development. While the political leadership has changed direction, other forces have taken hold. The environment is under threat, and the culture feels the strain of new forms of consumption.

Planet/Cuba examines how art and literature have responded to a new moment, one both more globalized and less exceptional; more concerned with local quotidian worries than international alliances; more threatened by the depredations of planetary capitalism and climate change than by the vagaries of the nation's government. Rachel Price examines a fascinating array of artists and writers who are tracing a new socio-cultural map of the island.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Planet/Cuba by Rachel Price in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

We Are Tired of Rhizomes

At first glance, recent Cuban literature seems to evince a renewed interest in the 1920s and 1930s. But the trend is primarily focused on European modernism or crisis, sometimes as it played out in Cuba, a sign perhaps of an eagerness to think beyond the nation. In Djuna y Daniel (Djuna and Daniel, 2008), for example, Ena Lucía Portela reconstructs the relationship between radical modernist figures Djuna Barnes and Daniel Mahoney, while in Posar desnuda en la Habana (Posing Nude in Havana, 2011), Wendy Guerra revisits the diaries of the Cuban-French Anaïs Nin.1 Leonardo Padura’s impressive reconstruction of Trotsky’s time in Mexico in the 1930s and 1940s tracks his assassin Ramón Mercader back to Cuba, but in the 1970s (El hombre que amaba a los perros/The Man Who Loved Dogs, 2009), while Padura’s exploration of the 1930s emigration of Eastern European Jews to Havana comes closer to examining the era with a focus on a little-known history of a Jewish quarter in Havana (Herejes/Heretics, 2013).2

Of course, Cuban authors have no obligation to write about Cuban history, which in any case is inextricably global. But it is notable that few writers seem interested in revisiting everyday life on the island during the same modernist period. The 1930s in Cuba were tumultuous. The decade saw both general and local strikes, a revolution in 1933, struggles against racism, the seizure of a sugar mill by workers, and the formation of anarchist circles with their own weekly publications—to dwell only on period politics, and to say nothing of the rich cultural production.3 Many of the issues motivating Republican-era unrest remain relevant today. At a moment in which cooperatives have been embraced as an experimental form for a new economy, it is striking that a collection of essays on cooperatives published in Cuba in 2009 addresses both historical, nineteenth-century examples from Europe and post-1959 cooperatives in Cuba, but passes over the history of early twentieth-century cooperatives on the island altogether.4

For the past half-century official discourse has denounced the first decades of the twentieth century as morally, politically, and economically corrupt. But political, aesthetic, and ecological experiments from the 1930s might productively be revisited in an uncertain present, and there are signs of fresh approaches to the period in both historiography and literature.5 Padura, for instance, the preeminent Cuban novelist publishing today, claims he became interested in novelizing Trotsky’s life precisely because the story was relatively unknown on the island and is important for rethinking the twentieth century.6 Recent activist coalitions and independent forums such as Observatorio Crítico (Critical Observatory)—which offers a heterodox, left critique of current government policies—are recuperating histories of anarchism on the island. Observatorio Crítico member Isbel Díaz Torres is also the main figure behind El Guardabosques (Rangers), a small ecological activist group based in Havana.

A few legacies and archives of ecological thought from the early part of the twentieth century, however, have managed to remain alive and relevant, if insufficiently known. In particular, José Manuel Fors’s photography and installations have, since the 1970s, engaged the figure of his grandfather Alberto S. Fors, the leading forester of the Republican period. José Manuel was a member of the New Cuban Art movement of the 1980s; today he continues to work on ecological themes, on the medium of photography itself, and on the relations between families and everyday objects. Connections between grandfather and grandson, scientist and artist have been revisited separately in articles by two of Havana’s leading curators, Cristina Vives and Corina Matamoros.7 Still, few studies of José Manuel Fors actually engage with his grandfather’s thought. Indeed, the artist himself has worked more with his grandfather’s iconography than with the engineer’s pioneering ecological philosophy. Yet reading Alberto S. Fors’s 1930s writing itself alongside contemporary philosophers suggests its renewed relevance for ecology and for a contemporary art already influenced by José Manuel Fors’s generation of ecoaesthetics.

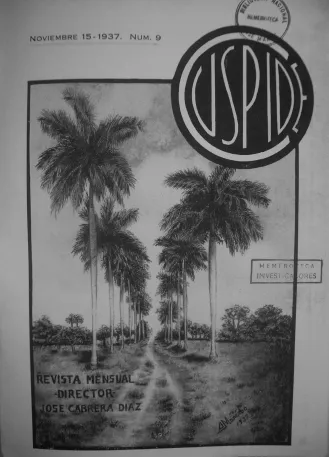

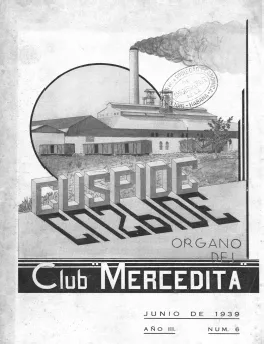

José Manuel grew up in his grandfather’s house alongside the latter’s xylotheque, a collection of Cuban woods. For decades he has appropriated his grandfather’s letters, writings, and photographs in his art, mining images and materials from his family history to meditate on nature and society. I will turn to an examination of these works at the end of this chapter, after considering in greater detail Alberto S. Fors’s ecological thought itself. Revisiting these archives and debates is neither aesthetic nor antiquarian, but urgent, as some of the ecological pressures that had occasioned critique in the 1930s return.8 Despite Fidel Castro’s dismantling of the sugar industry, for instance, the crop may prove resilient. As noted in the introduction, the Miami-based Fanjul family—whose ancestors owned the very sugar mill whose associated cultural club published many of Alberto S. Fors’s 1930s articles—have been in talks with leading economists for the Cuban government about reinvesting in the island, and in sugar. A review of the island’s 500-year-old struggle between forest and sugar may be newly urgent for contemporary ecological and aesthetic thought.9

Figure 1.1: Cúspide, November 1937.

Figure 1.2: Cúspide, June 1939.

In what follows I first look at contemporary art’s tropological interest in trees and environments. I then flesh out the backstory to these interests, tracing trees’ abiding centrality to Cuban ecological thought. The second half of the chapter turns to the little-known writings of Alberto S. Fors and to the visual art of José Manuel Fors, connecting the ecological aesthetics of the 1930s to those of the ’70s, ’80s, and the present.

Art’s New Arborism

What lies behind the current emphasis on trees, potentially so romantic and long the stuff of landscape painting? Early in A Thousand Plateaus (1980) the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari announced “we’re tired of trees.”10 Their proposal of the rhizome as an alternative, nonhierarchical model of association—underground, ramifying, horizontal—became, in the decades following the book’s publication, one of the most adopted symbols or structures for imagining and describing democratic collectivities (manifest, for instance, in the digital art website Rhizome, now linked to The New Museum in New York). As recently as 2013, the art journal Third Text cited Deleuze and Guattari as the inspiration for a special issue on ecoaesthetics.11 But as the “society of control” that Deleuze also diagnosed deepens—a society based on coding, in which control is not hierarchical and spectacular but pervasive and insidious, rather like climate change itself—it seems time to announce, only partially in jest, that we are now tired of rhizomes: we want trees.12

Works by a new generation of Cuban artists summon a longer-standing attention to trees in Caribbean ecology and art, reactivated in the context of current concerns. The young artist Rafael Villares, for instance, frequently works with trees and “environments,” blending aesthetic queries about the borders between subject and object with concerns about ecology. In Retoño (Shoot, 2009), Villares’s arm is but one more branch of a tree trunk, making the artist’s tool an extension of the nature in opposition to which techne was once imagined. Villares conceived of Retoño as an homage of sorts to the 1980s artists Juan Francisco Elso, José Bedia, and Ana Mendieta (discussed below); Mendieta had carried out a series of performances entitled The Tree of Life in 1976 and 1979, in which she camouflaged herself against the bark of a tree.13 Adonis Flores, whose work is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5, also made a piece named Retoño (2006), in which, dressed in camouflage, he shimmied up onto and hugged a high tree branch, becoming a growth along it.

In Villares’s series De la soledad humana (Of Human Solitude, 2009), the roots of a severed tree trunk hung suspended over a dimly lit gallery floor, casting an intricate shadow of criss-crossing networks that faded into the surrounding darkness. From inside the trunk, some 3 meters in diameter, emanated the sounds of birds, people, and branches moving in the wind. In the artist’s sketch for the piece, the ground appears as a globe. The shape suggests a planet no longer supportive of life, but inscribed with the shadows cast by the root system, severed and expelled from its surface. The structure of the piece inverts the order of things so that the roots of the earth’s ecologies are above us, and we below, under spiny shadows cast by the floating system, reminiscent of an aerial view of rivers running black.

In a work made for the 2012 Havana Biennial, Paisaje itinerante (Itinerant Landscape), Villares constructed a giant planter to hold a full-sized laurel tree, with room enough to include a wooden bench beside the tree and stairs leading up inside it. The entire structure hung from a crane and was moved four times during the biennial, principally to locations otherwise bereft of trees. The idea, Villares asserted, was to give habaneros a new perspective on their city: both from the tree’s heights, and through the addition of trees to an otherwise concrete cityscape. The piece is also a striking example of convergence among contemporary artworks interested in the intersections of the natural and built environments: although Villares was not aware of any precedents for his work, in 2010 the Brazil-based artist Héctor Zamora made an installation, documented in digital prints, titled Errante (Errant, similar even in title to Villares’s piece). Zamora suspended three separate trees rooted in giant clay-colored pots over São Paulo’s Tamanduatei River, which is channeled through cement retaining walls and flanked by multi-lane avenues coursing through the giant metropolis. Zamora, too, framed his suspension of potted trees over a barren cityscape as adding to and changing the experience of public space.14

Figure 1.3: Rafael Villares, De la soledad humana, 2009. Sound installation.

Paisaje itinerante is one of the most mature of Villares’s works, its humor, scale, and transience through different cityscapes a sophisticated engagement with perspective and with urban ecologies. It is subtle in its understanding of what environment means. Earlier of Villares’ works perhaps too easily presumed “nature” and “culture” to be stable categories, purveying common tropes about ecoart that Timothy Morton has recently attempted to pick apart. Morton writes that contemporary art that gestures beyond the gallery space (a stand of trees, the sound of water running) is “environmental” insofar as it attempts to erase the mediation between artist and nature, gallery and outside. Only taste, Morton notes, prevents us from seeing such installations as of a piece with more clearly kitschy “nature writing.”15 In both, artifice wishes to slink away and let nature step forth. For Morton, ecological art often pairs this “ecomimesis” (shunning mediation, imitating the environment) with a “poetics of ambience”: a poetics, that is, that aspires to model the dissolution of the division between subject and object that haunts Western philosophical concepts, a division that purportedly enables degradation of the environment.16

Figure 1.4: Rafael Villares, Paisaje itinerante, 2012. Installation.

Such a staging of ambience frames some of Villares’s environments, which risk restaging parts of the natural world as pleasing sensory experiences. An installation in which Villares transported a stand of bamboo and played the sound of its movement (Aliento/Breath, 2008), for instance, recalls Morton’s wry observation that the erasure between high and low “environmental” art is exemplified in minimalism’s translation into modern kitchens, or in the fact that “Bamboo has become popular in British gardens for its sonic properties.”17 Another sound installation, Respiro (Breath, 2010) consisted of a false floor of cracked earth laid over a lightbox some six by...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: A Treasure Map for the Present

- Chapter 1: We Are Tired of Rhizomes

- Chapter 2: Marabusales

- Chapter 3: Havana Under Water

- Chapter 4: Post-Panamax Energies

- Chapter 5: Free Time

- Chapter 6: Surveillance and Detail in the Era of Camouflage

- Notes

- Illustration Credits

- Index