- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

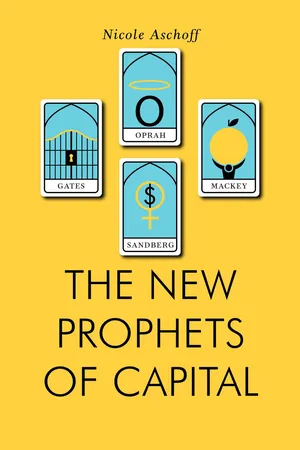

The New Prophets of Capital

About this book

As severe environmental degradation, breathtaking inequality, and increasing alienation push capitalism against its own contradictions, mythmaking has become as central to sustaining our economy as profitmaking.

Enter the new prophets of capital: Sheryl Sandberg touting the capitalist work ethic as the antidote to gender inequality; John Mackey promising that free markets will heal the planet; Oprah Winfrey urging us to find solutions to poverty and alienation within ourselves; and Bill and Melinda Gates offering the generosity of the 1 percent as the answer to a persistent, systemic inequality. The new prophets of capital buttress an exploitative system, even as the cracks grow more visible.

Enter the new prophets of capital: Sheryl Sandberg touting the capitalist work ethic as the antidote to gender inequality; John Mackey promising that free markets will heal the planet; Oprah Winfrey urging us to find solutions to poverty and alienation within ourselves; and Bill and Melinda Gates offering the generosity of the 1 percent as the answer to a persistent, systemic inequality. The new prophets of capital buttress an exploitative system, even as the cracks grow more visible.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The New Prophets of Capital by Nicole Aschoff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Sheryl Sandberg and the

Business of Feminism

Fifteen years ago Silicon Valley was inhabited by packs of brogrammers slouching around in hoodies and sandals, hacking code on bean bag chairs, and regurgitating South Park jokes. In the intervening years the start-up scene has changed—a bit. Computer technology has been mainstreamed, and women have joined the high-tech gold rush. Tech mammoths like Facebook, IBM, Yahoo!, Hewlett-Packard, and Google all employ women in leading roles.

But despite the power of women like Sheryl Sandberg, Ginni Rometty, Marissa Meyer, Meg Whitman, and Susan Wojcicki, the gender balance in Silicon Valley and the larger corporate world remains highly skewed, and most leadership positions are held by men. At tech companies only 2 to 4 percent of engineers are women; at Fortune 500 firms, 4 percent of CEOs are women. Boardrooms are a bastion of maleness, and many companies, like Twitter, have no women on their board. This disparity extends beyond corporate America: globally, 90 percent of heads of state are men, and at the 2014 World Economic Forum only 400 of the 2,600 representatives present were women, a 17 percent drop from the previous year. And 2013 marked the first time women held twenty seats in the US Senate.

This is the world into which Sheryl Sandberg, the chief operating officer of Facebook, launched her “sort of manifesto”, as she called it, in 2013.1 Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead addressed the persistent gender imbalance in elite jobs and announced Sandberg’s entrance into the century-old struggle for equality in the workplace. From her position of power atop the ping-pong tables and mini-fridges of tech-land, “feminism’s new boss” (as Gloria Steinem likes to call her) is exhorting more women to “lean in,” scale the “corporate jungle gym,” and not stop until they reach the top.

Sandberg’s manifesto is a New York Times bestseller and has sold over a million and a half copies. Sandberg has been pushing women to be more ambitious for a number of years, through female networking events in Silicon Valley, Women’s Leadership Day at Facebook, and monthly dinners for women at her home. In 2010 she extended her message through a TED Talk that went viral, and followed up with an equally popular 2011 commencement speech at Barnard College. Lean In revisits and expands the themes in these speeches and argues that women need to stop being afraid and start “disrupting the status quo.” “Staying quiet and fitting in … aren’t paying off.” Instead of waiting for someone to place a tiara on their heads, women need to seize the social and economic gains they want. If they do, Sandberg believes this generation can close the leadership gap and in doing so make the world a better place for all women.2

Like many prophets before her, Sandberg makes her case by telling the story of her own path to success. Sandberg worked her way up to the top from middle-class beginnings: her father was an ophthalmologist and her mother was a French teacher turned stay-at-home mom. She graduated from Harvard, twice, and has worked in high-power jobs at the US Treasury, Google, and now Facebook. Industry types consider her a “rock star in business, politics, and popular culture, with unprecedented influence and reach.”3 She is worth more than a billion dollars and was listed at number six on the Forbes 2013 Most Powerful Women List, sandwiched between Hillary Clinton and Christine Lagarde of the International Monetary Fund. Sandberg has been so successful at making Facebook profitable that companies want to clone her. Andreessen Horowitz, Facebook board member and cofounder of the Andreessen Horowitz venture capital firm says of Sandberg: “Her name has become a job title. Every company we work with wants a Sheryl.”4

Feminist Ideals and Reality

The runaway success of Lean In and, more broadly, the resurgent interest in feminism in wealthy countries, stem from widespread frustration with the advancement of women. Though women in the United States have, roughly speaking, equal rights and access to education, nutrition, and health care as men, the picture for women is disappointing and progress has been slow and halting. Women outperform men in higher education but don’t achieve comparable levels of success or wealth. Decisions about balancing home life and work life are as fraught as ever as housing and childcare costs continue to climb. Women are still stereotyped or under-represented in the popular media—of the 100 highest-grossing 2012 films, only 28.4 percent of speaking characters were women. The backlash against women’s reproductive rights continues unabated, with states like Texas passing draconian abortion legislation. After a long, steady decline through the 1990s, rates of violence against women haven’t budged since 2005.

For poor women—especially women of color—the situation is far bleaker. Low wage, contingent, and precarious work remains dominated by women. As the income and wealth gap between the rich and poor yawns ever wider, women at the bottom seem to be disappearing from view. The Right doesn’t talk about “welfare queens” anymore because state safety net provisions have been all but eliminated and replaced by homeless shelters and food banks. Poor women are more likely to be victims of domestic violence than wealthy women, prevented by poverty and isolation from escaping abusive relationships. A recent report showed that white, female high school dropouts have seen their life expectancy drop by five years over the past two decades.

When Congress passed the Equal Pay Act in 1963, most women, especially those with young children, worked only in the home. In the fifty years since then the situation has reversed. Today 60 percent of women work outside the home. Single and married mothers are even more likely to work, including 57 percent of mothers with children under the age of one. Yet women who work full time still earn only 81 percent of full-time male earnings. This disparity would actually be greater if men’s wages (aside from BA degree holders) had not fallen faster than women’s in recent years. The wage gap widens when women have children. Women in their early twenties make just over 90 percent of what their male counterparts take home. But between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-four women’s relative pay takes a nosedive and continues to decline between thirty-five and forty-four. The divergence illustrates both the unbalanced effect of family care responsibilities and expectations on women and the dramatic effect of pricey childcare and inflexible work schedules on women’s earning power.5

Surprisingly, the widest pay gaps occur in professional and higher-paying jobs. While this elite job pay gap is in part the result of women “off-ramping” after having children, a significant component comes from gatekeeping and professional networks that keep women out of top jobs. When a female student at Harvard Business School asked William Boyce, co-founder of Highland Capital Partners, for tips on entering the venture capital field he laughed and said, “Don’t.” Boyce wasn’t just channeling Don Draper—he felt that he was doing the student a solid by letting her in on the secret that men in finance do not want female peers.6

While pay gaps are higher at the top, feminists like bell hooks argue that sexism and racism pervade all corners of society. Dominant narratives of power glorify white, heteronormative visions of life. From birth, boys and girls are treated differently. Assertive girls are called bossy and shamed for aggressive behavior while boys are expected to take charge. Girls are given dolls to play with while boys are given blocks and computer games. Gender stereotypes introduced in the home, school, and everyday life are perpetuated throughout women’s lives, shaping their identities and life choices. Men choose higher-paying science and math careers while women gravitate toward lower-paying, language-oriented professions.

At the societal level stereotypes intersect with material conditions to create a gendered, racialized division of labor. The retail, service, and food sectors—the center of new job growth—are dominated by women, and the feminization of “care” work is even more pronounced. Women make up 82 percent of elementary school teachers, 90 percent of nurses, 90 percent of housekeepers, 94 percent of child care workers, and 87 percent of personal care workers. In September 2013 President Obama extended the Fair Labor Standards Act to domestic workers (finally), and some states, like California, have passed a domestic worker bill of rights. Despite these significant steps forward, care work is still seen as women’s work and undervalued. Disproportionate numbers of caring jobs are low-paying, contingent gigs in which humiliation, harassment, assault, and wage theft are the norm.7

Are Women Their Own Worst Enemies?

All feminists recognize the systemic aspects of women’s subordination, but some, like Sheryl Sandberg, don’t believe that the laundry list of external barriers explains the persistent failure of women to take their rightful place as equal members of society. Sandberg argues that internal barriers are as critical, if not more critical, in explaining women’s lives and disappointments.

Betty Friedan exemplified this internal-barriers, get-tough message, and rocked the boat in a big way with her 1963 manifesto The Feminine Mystique. Writing near the end of the postwar boom, Friedan discovered that the feminist revolution wasn’t over and that women weren’t taking advantage of the choices available to them in life. She argued that women in her day often fell victim to “a mistaken choice” between being the “career woman—loveless, alone” or the “gentle wife and mother—loved and protected by her husband, surrounded by her adoring children.”8 According to Friedan, women were making the wrong choice. Young, educated, middle-class women willingly surrendered to domesticity rather than struggle through the rite-of-passage identity crisis that young men were destined to endure. “It is frightening to grow up finally and be free of passive dependence. Why should a woman bother to be anything more than a wife and mother if all the forces of her culture tell her she doesn’t have to, will be better off not to, grow up?”9

In her characteristically bold prose Friedan argued that this surrender left a generation of (middle-class, suburban) women with half-formed identities, perpetually stunted and immature, and that domestic escapism often led to depression, bad parenting, adultery, alcoholism, and even suicide. The only way a woman could become a fully formed adult was to get an education and then passionately follow her intellectual interests to a career outside the home.

Sheryl Sandberg is in many respects extending the argument Friedan made, but instead of telling women to get out of the kitchen, Sandberg commands them to get out of the cubicle. She thinks women need to wake up and recognize the invisible, internal forces pushing them down the long, languid road to mediocrity. These internal barriers, while often ignored, are incredibly important, and unlike external barriers, “are under our own control.”10

Sandberg believes that women talk themselves out of taking power because they feel like frauds and doubt their own capabilities, and because they face resistance from a culture that penalizes “aggressive and hard-charging” women who “violate unwritten rules about acceptable social conduct.”11 Women worry so much about work/life balance and whether “having it all” (family and career) is really possible that they often give up before they have to, putting their foot on the brakes when they should be putting their foot on the gas. Women still face a “mistaken choice”:

women are surrounded by headlines and stories warning them that they cannot be committed to both their families and careers. They are told over and over again that they have to choose, because if they try to do too much, they’ll be harried and unhappy. Framing the issue as “work-life balance”—as if the two were diametrically opposed—practically ensures work will lose out. Who would ever choose work over life?12

Women’s decisions to give up on their ambitions as adults are often the result of learned dispositions and habits acquired during childhood. But despite this socialization and its long-term effects, Sandberg doesn’t really believe in glass ceilings or see the need for affirmative action. She thinks the main force holding women back—at least educated women—is their own hang-ups and fears. Women don’t need favors, they just need to believe in themselves. “Fear is at the root of so many of the barriers that women face … Without fear, women can pursue professional success and personal fulfillment.”13 Deborah Gruenfeld calls Sandberg a post-feminist—a woman who believes that “when you blame someone else for keeping you back, you are accepting your powerlessness.”14

So how should women take power and the corner office? Women must face their fears, be aggressive, sit at...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Storytelling

- 1. Sheryl Sandberg and the Business of Feminism

- 2. Capital’s Id: Whole Foods, Conscious Capitalism and Sustainability

- 3. The Oracle of O: Oprah and the Neoliberal Subject

- 4. The Gates Foundation and the Rise of Philanthrocapitalism

- 5. Looking Forward

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgements