- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

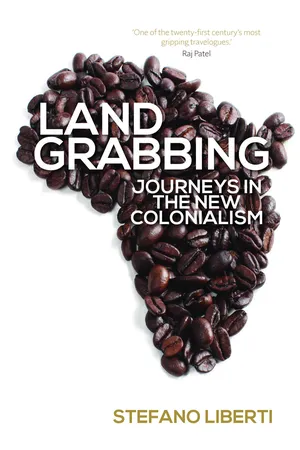

To the governments and corporations that are currently buying up vast tracts of the Third World, it is called "land leasing." To its critics this new era of colonization is nothing more than "land grabbing." In this arresting account of how millions of hectares of fertile soil are being stolen to feed the wealthy thousands of miles away, journalist Stefano Liberti takes us from a Dutch-owned model farm in Ethiopia to an international conference in Riyadh, where representatives of Third World governments compete to attract the interest of Saudi investors; from institutional and commercial meetings in Rome to the headquarters of the Landless Workers' Movement in S?o Paulo.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Land Grabbing by Stefano Liberti, Enda Flannelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Colonialism & Post-Colonialism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Ethiopia: An Eldorado for Investors

The first thing you notice is the vastness. Flourishing lands that extend as far as the eye can see. Green hills that roll down to the banks of a crystal water lake. Just below the plateau, the harshness upon which Addis Ababa rises softens into a landscape that looks like Paradise. The sun is shining. The air is pure. It seems a world away from the stifling atmosphere in the capital, where the exhaust fumes merge with whatever little oxygen is available at an altitude of 2,300 metres. This is Awassa, in the heart of the Ethiopian Rift Valley, 300 kilometres south of Addis Ababa. The surrounding countryside is breathtaking in its beauty. The road into town is lined with the hoardings of agricultural companies. There’s a symbol, a name, sometimes a telephone number of an office far away. Nothing to be seen beyond the gates, apart from endless stretches of seemingly uncultivated land.

But behind these very same gates, at a safe distance from prying eyes, lies the final frontier of this African country’s agricultural development: high-tech greenhouses in which grow legumes, fruits, vegetables, or plants cultivated for the so-called agrofuels – a development that Ethiopia has entrusted to foreign investors through a gigantic long-term rental plan that has transformed it into a destination for businessmen and adventurers from the other half of the planet.

I’ve come here to Awassa to visit one of these agricultural companies: Jittu International. ‘The most avant-garde industrial farm in all of Africa’, says its manager Gelata Bijiga, with pride and a little exaggeration, as I park my car after travelling the three kilometres of dirt road that separates the entrance gates from the greenhouses.

Gelata doesn’t waste much time on pleasantries. He greets me with a handshake and takes me on a tour. His boss – the Dutch agronomist Jan Prins, who I had talked to shortly before on the phone – has instructed him to show me around, and he is more than happy to do so. We enter the first greenhouse: an expanse of red tomatoes, mature and succulent. Grouped in bunches of five, they dangle with an almost unnatural symmetry from luxurious plants. As the manager leans over the seedlings, inspecting them carefully and cupping them in his hands to determine their progress, he reels off the company’s statistics: a thousand hectares of land, a thousand employees and eight greenhouses – soon to be increased to sixteen.

These eight greenhouses are just the first phase of a project that is rapidly expanding. All kinds of everything are grown here, from tomatoes to aubergines, zucchinis to peppers. The produce is perfect, showing the same standard size and brilliant colours that we expect to see in the aisles of our supermarkets. Each greenhouse presents a different kind: red peppers here, green peppers there. Long aubergines here, round ones there. Some are familiar to westerners, others are more exotic, looking like the fruit of a possible alien mutation: one side of a greenhouse contains tomatoes with yellow skin and a white interior. They look strange, but taste just as good as the more common type. Gelata moves among the plants with consummate ease. He points out the various experiments. He highlights the respective qualities of each product. He offers a wealth of detail in describing the latest techniques applied to these intensive crops. ‘The hoses for the irrigation system extend between the rows. The system is regulated by a centralised information system and provides the plants with precisely the right amount of water and fertilisers’, he tells me enthusiastically. The project is a roaring success. The company is making huge profits. Over the next two years, the manager assures me, production will triple at the very least. Specifically engineered to cater for the target market thousands of kilometres away, these succulent tomatoes, these red, green and yellow peppers, these aubergines as smooth as a baby’s skin, aren’t destined for the Ethiopians, but for the infinitely wealthier consumers in the Arab Gulf states. ‘Whatever we produce here is for exportation. In twenty-four hours we can transport our produce from here to the consumer, in some restaurant in Dubai.’ The goods are picked and placed in crates, put in refrigerators and taken by truck to Addis Ababa. Once there, they are loaded onto planes headed for the Middle East, the United Arab Emirates or Saudi Arabia.

Just as the produce is destined for overseas, likewise the company’s investors and, to a certain extent, its infrastructure are also foreign: the seeds are imported from the Netherlands, along with the computerised irrigation system; the greenhouse structures were developed by Spanish engineers, and the fertilisers also come from Europe. The firm run by Jan Prins resembles a sort of extraterritorial enclave: the irrigation system, the hyper-technological greenhouses, even the end products – so perfect because they are the result of genetic experimentation – are in total contrast with the surrounding landscape, which consists of land tilled by oxen or by farmers with hoes whose backbreaking work is done totally by hand on small plots. In the Jittu greenhouses there are computer rooms which constantly monitor the temperature, the pH of the earth, the quality of the water absorbed. Beyond the gates, the small straw and clay tikuls house entire families of farmers and the few animals in their possession. The feeling is one of passing, in the space of a few kilometres, from the Middle Ages to the most advanced modernity. The operation and yield of the greenhouses are certainly impressive, but appearances can be deceptive. There is one crucial aspect without which the picture is incomplete. This company, which to the locals must seem like a UFO that has chosen to land on the fields of Awassa, avails itself of two typically local elements: the land and the workforce. Elements with two characteristics that render them unbeatable: high productivity and a very low cost.

Hundreds of men and women are picking the vegetables in the greenhouses. Hundreds more work in the packing department. They work in silence, and their movements seem mechanical: one woman puts tomatoes in groups of forty in a box, another wraps them up, then a young man carries the crate to the fridge until the next truck takes it away. The room is large and well organised. The vegetables are arranged according to type. They are put into crates which are then stacked in an orderly fashion. At regular intervals someone moves them to the fridges. The average daily wage of these people is 9 birr, or 40 euro cents.

Gelata, who has an agronomy degree from Jimma University, has been working for Jittu Horticulture for three years. His salary, which he prefers not to reveal, is obviously higher than that of his compatriots who work in the fields, but he doesn’t seem too scandalised by this state of affairs: ‘This is Ethiopia, we can’t be offering salaries higher than what is normally earned here. In any case, we give these people training. We teach them a trade.’

The Jittu company is not a sweatshop. It is simply acting within the acceptable parameters of the market, which in these parts means labour and land at dirt cheap prices, and therefore enormous profits. Besides, the Ethiopian Investment Agency, which promotes foreign investment in the country, explicitly highlights this aspect on its website: ‘Labour costs in Ethiopia are lower than the African average’ (www.ethioinvest.org). Jan Prin’s company has merely seized the opportunity that the Ethiopian government has been promoting for the past five and a half years to those businessmen who have a bit of money to spend and a degree of know-how to put into play. At the end of 2007, Addis Ababa launched a plan for the long-term rental of parts of its land to investors bent on making them productive. It was met with enthusiasm by groups from across the world – mostly Saudis and Indians but also Europeans – who lost no time in acquiring lands on which they could start large-scale production. They are growing, or planning to grow, all kinds of produce: rice, tea, vegetables, cereals, cane sugar, as well as many plants used for making agrofuels, from jatropha to palm oil. So far, about a million hectares have been allocated. The plan foresees the assignment over the next few years of a total of about three million hectares – roughly the same land size as Belgium. The rental rates are extremely low, ranging from 100 to 400 birr (4 to 16 euros) per hectare for one year, depending on the quality and position of the land. In Gambella, a remote region on the border with South Sudan where most of the land has been put on the market, the rent is a mere 15 birr per hectare (60 euro cents). These favourable regulations, together with low labour costs and the many other benefits bestowed by the government, make Ethiopia one of the places in the world with the highest return on investment in agriculture. ‘This is an Eldorado for an agricultural investor’, says a visibly pleased Gelata, while showing me a row of identical bright green zucchinis, every one just the right size to fit into a crate that will soon be closed and sent to the Persian Gulf.

The Sheikh of Addis Ababa

The wholesale leasing of Ethiopian land (and of land in many other African countries) is the result of a typical market mechanism: the meeting of an alluring offer and a rapidly rising demand. That demand became an urgent necessity following an event of global proportions: the food crisis of 2007–8, which led to prices rocketing for basic foods such as rice, grain, corn and sugar. Although it is true that much media attention was given to the food riots that inflamed many African, Asian and Central American states, the crisis also stirred more than a few feathers in many areas that are normally less turbulent. The Arab Gulf states started to fear that they would be left without food, despite their enormous cash resources. This is because the market works in fickle ways. The hike in prices didn’t just lead to an increase in costs, but also had a more dangerous medium-term effect: in many producing nations, especially those producing rice, protectionist measures began to be implemented that sought to block exportation. This led to the first shortages in importing countries, with potentially devastating effects. Alarm bells sounded in Riyadh, but also in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, leading to a new policy that was given absolute priority by those in charge: to guarantee full control of the food supply at whatever cost, in order to be immune from the storms that shake international commerce. Given that it’s a Herculean task to grow rice in the desert, the Saudi rulers and their counterparts in the Emirates opted for a faster solution: to produce the food they needed elsewhere.

That perfect elsewhere was Ethiopia. Geographically close, rich with fertile land and graced with an excellent climate which permitted exceptional returns, the African country immediately revealed itself to be the best candidate for the role of ‘Granary of the Persian Gulf’. Added to this was the fact that the Ethiopian land market was ready to open up to outside investors, not least due to the savvy dealings and networking skills of a man who was to establish himself as unmistakably the best negotiator in Saudi-Ethiopian relations: the billionaire Mohammad Hussein Al Amoudi. Born of an Ethiopian mother and Yemeni father, this naturalised Saudi sheikh is one of the fifty richest men in the world, according to Forbes magazine. A close confidante both of King Abdullah and the high command of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) led by Meles Zenawi,1 the sheikh has built a veritable empire through his consortium, Midroc, which runs industries, hotels, hospitals and shopping centres. His investments in Ethiopia, like those he has made worldwide, have expanded into every sector in which there’s a profit to be made: from hydrocarbon to infrastructure and from finance to telecommunications. Given the crisis brought about by the food shortages, it was inevitable that the sheikh would pounce on the latest golden-egg-laying hen: intensive agriculture. The story goes that Al Amoudi responded to the concerns expressed by the royal family in Riyadh by bringing King Abdullah a sack of rice produced in Ethiopia. The king, mesmerised by the exceptional quality of the rice, gave him carte blanche to become the overseer of the Saudi’s agricultural investment plan in Ethiopia.

Whether or not there’s any truth to this story, since late 2008 Al Amoudi has thrown himself into organising delegations, promoting meetings and expanding networks. This series of public relations endeavours resulted in the Saudi–East African Forum, a meeting between Saudi ministers and entrepreneurs and leaders from seven East African nations, which took place in November 2009 in Addis Ababa. The event saw the participation of representatives from fifty large Saudi companies and four of the kingdom’s ministers, all with the intention of ‘promoting a unique partnership between the vast technological and financial resources of the world’s largest exporter of oil and the unlimited human and natural resources of the “tigers” of East Africa’.2 Shortly before the Forum took place, Al Amoudi had created a new company – the Saudi Star Agricultural Development plc. – whose business target was the acquisition of land with the purpose of investing in the agricultural sector. ‘Sheikh Mohammad is increasingly interested in abandoning urban areas in order to concentrate on agriculture and agricultural production’, reiterated his consultant, spokesman and Saudi Star factotum, on the eve of the summit in Addis Ababa.3

No sooner was it said than done: from that point on, investment in the agricultural sector took off at lightning pace. Today, Al Amoudi directly controls three farms in Ethiopia, including 10,000 hectares of land in the Gambella region, where he produces rice for export to Saudi Arabia. Negotiations are underway with the government for another 300,000 hectares. Even Jittu Horticulture in Awassa is a sister company of Al Amoudi’s empire. Although formally independent, the fact is that Jittu obtained the land through a concession from the sheikh, who in turn rented it from the government.

The land belongs to the people (and to those who govern the people)

In Ethiopia, the only legitimate owner of land is the state. Upon coming to power in 1991 after ousting the ‘red dictator’ Mengistu Haile Mariam, the EPRDF decided to maintain the same system for controlling the land that existed under the DERG socialist regime. Ethiopia at the time was a disaster zone, ravished by drought and famine, a name that conjured images of stunted children with swollen bellies, the desperate recipients of money raised by Bob Geldof, Bono and a cast of other stars at Live Aid in 1985. Many people, at the height of the collective emotion generated by this global event – the ‘concert for Ethiopia’ – blamed the famine on baneful land management by DERG, whose ‘agrarian socialism’ banned private property and tried to group or force farmers together in cooperatives under the party’s control. When the rebels, led by Meles Zenawi, came to power, everybody expected them to quickly enact agrarian reform. But to the great discomfort of the international donors – primarily the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, who were hoping for large-scale privatisation of the land – the new government immediately confirmed DERG’s land policy, and then, in 1995, wrote the principle of ‘the public property of land’ into the constitution, with article 40 declaring that ‘the land is the common property of the nations, nationality and people of Ethiopia’.4

According to this principle, therefore, it falls to the state, through its regional and local offices (the so-called woreda and kebele) to bestow cultivable land, and the benefactor holds no right of ownership, but is merely given permission to use the land. Inspired by the principle of egalitarian justice, this policy won the favour of rural populations, who still clearly remembered the great iniquity of the imperial period, when the land was controlled by a handful of landowners. But it also provided the government with a formidable source of power: in a country in which 85 percent of the population lives in the countryside and earns its living by farming, whoever controls the land controls the people. It is, then, the state who grants the arable land, whether to the farmers who need it for their own sustenance or to large investors, be they local or international.

But in what way and to whom is access given to what looks to be an extremely profitable investment? To find out, I pay a visit to a new residential area on the outskirts of the capital, to which a number of public offices have been moved. The area is a mass of building sites, a sign of the gigantic property boom that is changing the urban landscape here. Over the past few years, Addis Ababa has become one long and uninterrupted ‘work in progress’. In every corner of the city, buildings are going up, foundations are being dug, cement is being laid, although it’s difficult amid this construction fever to see any overall logic in what’s being done. The Ministry for Agriculture and Rural Development is a nondescript building on one side of a pot-holed road without asphalt, further proof of the lack of planning involved in the city’s development. I have an appointment here with Esayas Kebede, the Director of the Ministry’s Agency for Investment, founded in 2009 to further strengthen ties between the government and potential investors. Kebede is the person to talk to. He is the one the investors come to see when they want to acquire land in Ethiopia, and it is on his desk that the various business plans of groups who want to enter this sector inevitably end up. It is he – at least formally – who decides if the plans are valid and if the companies are deserving of obtaining plots of land. As I look for him I wander at random through the various rooms of the Ministry. With no usher to direct me, I get a chance to observe how the different levels of power operate in an Ethiopian public office. The rooms are large open spaces: there are about ten desks on each side and an empty space in the centre. The desks are all the same size, but what differs is how full each one is: some, in fact, are completely bare. The people sitting at them have been graced with nothing more than a sheet of paper and a pen, a clear sign that they belong on the lowest rung in the ministerial hierarchy. Others are covered with file boxes, indicating that those working at them are mid-level functionaries whose job is to examine the dossiers. Then come the few who have that real and unmistakeable symbol of power: a computer....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface to the English-Language Edition

- Introduction

- 1. Ethiopia: An Eldorado for Investors

- 2. Saudi Arabia: Sheikhs on a Land Conquest

- 3. Geneva: The Financiers of Arable Land

- 4. Chicago: The Hunger Market

- 5. Brazil: The Reign of Agribusiness

- 6. Tanzania: The Frontier for Biofuels

- Appendix I: Updates on the Web

- Notes