- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

**Winner of the 2019 Sussex International Theory Prize**

Despite the science and the summits, leading capitalist states have not achieved anything close to an adequate level of carbon mitigation. There is now simply no way to prevent the planet breaching the threshold of two degrees Celsius set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. What are the likely political and economic outcomes of this? Where is the overheating world heading?

To further the struggle for climate justice, we need to have some idea how the existing global order is likely to adjust to a rapidly changing environment. Climate Leviathan provides a radical way of thinking about the intensifying challenges to the global order. Drawing on a wide range of political thought, Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann argue that rapid climate change will transform the world's political economy and the fundamental political arrangements most people take for granted. The result will be a capitalist planetary sovereignty, a terrifying eventuality that makes the construction of viable, radical alternatives truly imperative.

Despite the science and the summits, leading capitalist states have not achieved anything close to an adequate level of carbon mitigation. There is now simply no way to prevent the planet breaching the threshold of two degrees Celsius set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. What are the likely political and economic outcomes of this? Where is the overheating world heading?

To further the struggle for climate justice, we need to have some idea how the existing global order is likely to adjust to a rapidly changing environment. Climate Leviathan provides a radical way of thinking about the intensifying challenges to the global order. Drawing on a wide range of political thought, Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann argue that rapid climate change will transform the world's political economy and the fundamental political arrangements most people take for granted. The result will be a capitalist planetary sovereignty, a terrifying eventuality that makes the construction of viable, radical alternatives truly imperative.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Climate Leviathan by Joel Wainwright,Geoff Mann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Volkswirtschaftslehre & Umweltökonomie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

1

Hobbes in Our Time

Auctoritas non veritas facit legem (Authority, not truth, makes law).

Hobbes

I

Carl Schmitt once wrote that “state and revolution, leviathan and behemoth, are actually or potentially always present”—that “the leviathan can unfold in unexpected historical situations and move in directions other than those plotted by its conjurer.”1 For Schmitt, the modern thinker most closely associated with Thomas Hobbes and his Leviathan, this was no minor point of order. Leviathan, whether in the Old Testament or in even older myths, was never a captive of its conjurer’s will and remains at large today, prowling between nature and the supernatural, sovereign and subject. Yet Leviathan no longer signals the many-headed serpent of the eastern Mediterranean, but Melville’s whale and Hobbes’s sovereign, the “Multitude so united in one Person” to form the “Common-wealth”:

This is the Generation of that great Leviathan, or rather (to speak more reverently) of that Mortall God, to which wee owe under the Immortall God, our peace and defense. For by this Authoritie, given him by every particular man in the Common-Wealth, he hath the use of so much power and strength conferred on him, that by terror thereof, he is enabled to forme the wills of them all, to Peace at home, and mutuall ayd against their enemies abroad … And he that carryeth this person is called Soveraigne, and said to have Soveraigne Power; and every one besides, his Subject.2

How did this figure of sovereign power come to be called Leviathan? Hobbes does not say, but the reference is certainly to the Book of Job. Job, abused by misfortunes cast upon him by Satan, cries out against the injustices visited upon the faithful. God’s reply is neither kind nor comforting: he reminds Job not only of His justice, but of His might. God taunts Job with the Leviathan, proof of His worldly authority and of Job’s powerlessness:

Can you pull in the leviathan with a fishhook or tie down his tongue with a rope?Can you put a cord through his nose or pierce his jaw with a hook?Will he keep begging you for mercy? Will he speak to you with gentle words? …Any hope of subduing him is false; the mere sight of him is overpowering.No one is fierce enough to rouse him. Who then is able to stand against me?Who has a claim against me that I must pay?Everything under heaven belongs to me. […]On earth [leviathan] has no equal, a creature without fear.He looks down on all that are haughty; he is king over all that are proud.3

Although this reference to a worldly king suggested the metaphor of Leviathan to Hobbes, it was very roughly transposed.4 As Schmitt is at pains to explain, Hobbes’s personification of the emerging form of state sovereignty as Leviathan “has obviously not been derived from mythical speculations.”5 Rather, in the text that bears its name, Leviathan is put to work for different purposes. Leviathan, a sea monster who seems the very embodiment of nature’s ferocity, is figured by Hobbes as the means to escape the state of nature. As Schmitt indicates, Hobbes’s sovereign is a machinic antimonster. And, unlike God’s taunts to Job, its sovereignty is not rooted in mere terror, but grounded in a social contract.

Schmitt claimed his 1938 philology of Leviathan was a response to Walter Benjamin that has “remained unnoticed”—specifically, to Benjamin’s “Critique of Violence” of 1921. The real point of contention is crystallized in what Giorgio Agamben calls the “decisive document in the Benjamin–Schmitt dossier,” that is, Benjamin’s thesis VIII on history:6

The tradition of the oppressed classes teaches us that the “state of emergency” in which we live is the rule. We must attain to a concept of history that is in keeping with this insight. Then we shall clearly realize that it is our task to bring about the real state of emergency.7

Since the United States inaugurated its most recent states of emergency through wars on terror and economic crisis, Benjamin’s eighth thesis has received a lot of attention, and rightly so. Much of this work has been inspired by Agamben’s claim that “the declaration of the state of exception has gradually been replaced by an unprecedented generalization of the paradigm of security as the normal technique of government.”8 The ecological crisis has been largely excluded from this discussion. This is a pity because the regulation of security under exceptional conditions is increasingly a planetary matter. Even more than economic crisis, it is global climate change that has produced the conditions in which “the paradigm of security as the normal technique of government” is being solicited at a scale and scope hitherto unimaginable. What will become of sovereign security under conditions of planetary crisis? Is a warming planet “fierce enough to rouse” Leviathan? Or will Leviathan “beg for mercy”?

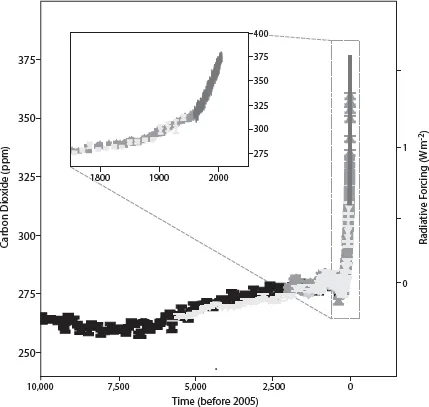

Perhaps this seems hyperbolic—perhaps the genie of carbon emissions can be stuffed back in the bottle. But where is the push to mitigate carbon? The long-term trends, which provide the clearest signal, are obvious: since the birth of fossil-fueled capitalism in England, carbon emissions have risen steadily. As that social formation has spread and reformed the world, emissions have grown exponentially. The graph of the quantity of CO2 in the atmosphere since the emergence of humans approximately 200,000 years ago looks relatively flat until the early nineteenth century. In only the most recent 0.01 percent of human history, everything has changed (see Figure 1.1.) The World must somehow break this so-called hockey stick. We are nowhere near doing so.

Figure 1.1. Atmospheric CO2, past 10,000 years, the infamous ‘hockey stick’

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Fifth Assessment Report, Working Group I, 2013, available at ipcc.ch.

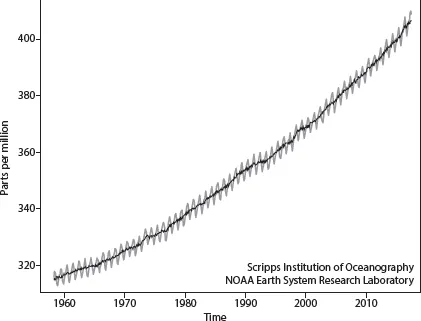

Even with very slow economic growth after 2007, global carbon emissions jumped by 2.2 percent between 2000 and 2010 (see Figure 1.2).9 This was the fastest decadal increase in emissions ever recorded, but it is likely to be surpassed in 2010–2020 as global CO2-equivalent emissions continue to climb, driven by increasing emissions in East Asia, the world’s center of commodity production.10 Capital’s drive for profit locks in policies for growth, whatever the cost. One clear signal since 2007–2008 is that elites everywhere, faced with prospects of slow economic growth, are prepared to act swiftly and commit bottomless public funding to prime the pump. The need for profit also locks in infrastructure with devastating climatic implications. In 2012 the International Energy Agency, hardly a revolutionary outfit, warned that without a change of direction, by 2017 the world would have energy infrastructure that “locked in” emissions at a scale that closed “the door” on the possibility of limiting global warming to non-disastrous levels. That infrastructure has since been built.11 Consistent with the agency’s warning, reports from science have grown ever more fantastic as the climatic and ecological implications intensify.

Figure 1.2. Monthly mean atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa Observatory, 1958 – 2017

Source: Earth System Research Laboratory, Global Monitoring Division, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, July 2017, available at esrl.noaa.gov.

We presume our audience knows the basics, and to avoid hyperbole we will refrain from appealing to frightening headlines from scientific reports. Furthermore, beyond an appreciation of the scientific consensus on climate change, it is not clear that scientific literacy is necessary to grasp the political-economic transformations required, and many who understand the science are not on our side. The political problems we face cannot be fixed by simply delivering science to the masses. If good climate data and models were all that were needed to address climate change, we would have seen a political response in the 1980s. Our challenge is closer to a crisis of imagination and ideology; people do not change their conception of the world just because they are presented with new data. Despite the many dire signals, most people in the global North still find comfort in the belief that the worst consequences—scarcity of food and water, political unrest, inundations and other so-called “natural disasters”—are far enough away or far enough in the future that they will not live to experience them.

That reaction, although ethically unjustifiable, is nevertheless understandable, because the negative consequences of climate change sound out in two rhythms that are not synchronized.12 There is, on one hand, the almost imperceptible background noise of rising seas and upward ticking of food prices, punctuated, on the other hand, by the occasional pounding of stochastic events. When we started this book in 2010, the northern hemisphere cooked through the hottest summer on record; when we finished it in 2017, those records, already beaten, were surpassed again, month after month. There is no part of the world that has not changed dramatically. Yet as soon as unheralded events occur—wildfires in Russia and Canada, floods in Pakistan and England, coral bleaching in Australia and Belize, species declining everywhere—they are rinsed and lost by the quotidian wash of whatever comes next. The biggest events have a sound of their own, the high-pitched scream of emergency. But because the background noise ultimately is this emergency in latent form, the true tone of climate change is not yet properly heard. Neither is Benjamin’s call for a “real state of emergency,” to which we return in Chapter 8.

Meanwhile, the ongoing wars for the world’s energy supplies are waged on multiplying fronts. Consider the Arctic, which concentrates all the contradictions of our conjuncture into one geographical region. Warming has reduced the polar ice cap so rapidly that we can expect ice-free ship passage by 2030.13 Rather than spark a rush to cut off fossil fuel exploitation, this terrible manifestation of our planetary emergency has provoked a new geopolitical struggle—led by Russia, China, the United States, and Canada—to control the flow of resources from and through the north, especially fossil fuel energy. The leading capitalist states thus address the problems they have created by deepening the same problems.14

In the face of these trends it is difficult to contemplate the future calmly. Merely to confront our perils can paralyze us with fear. As Mike Davis says, “on the basis of the evidence before us, taking a ‘realist’ view of the human prospect, like seeing Medusa’s head, would simply turn us into stone.”15 We have done our best to suppress that dread and wrote Climate Leviathan to think through the political-economic futures that climate change seems to us most likely to induce. The mandate for that undertaking, for all its limitations and guesswork, stems from the looming political-economic formations that are no small part of our peril. Above all, we must not be afraid to ask hard questions.

II

To begin, consider two very difficult clusters of questions. First, if the world is to achieve the massive reductions in global carbon emissions we know are necessary, how might we do so? What political processes or strategies could make that happen in anything resembling a just manner? In other words, can we conceive of revolution(s) in the name of climate justice, and if so, what do they look like? Second, if carbon emissions do not decline adequately (as seems highly likely to us, for reasons explained below), and climate change reaches some threshold or tipping point at which it is globally impossible to ignore or reverse, then what are the likely political-economic outcomes? What processes, strategies, and social formations will emerge and become hegemonic? Can the defining political-economic formation of the modern world—the capitalist nation-state—survive catastrophic climate change? If so, how, and in what form? Do we have a theory of how capitalist nation-states are transforming as a consequence of planetary change?

We posit that presently, we have few if any answers to these questions. Our challenge, to develop a politics adequate to the current conjuncture, calls for all of us who identify with the emerging global movement for climate justice to elaborate responses to these problems. This will not be easy of course. Coherent answers are not only a matter of theory, but also of forms of political struggle that sound out the barriers to and prospects for social and ecological transformation.

Many are thinking through these questions. There is a raft of recent scholarship on climate change and the prospects for political change, with especially significant contributions from environmental sociology, critical human geography, and international relations.16 Yet given that climate change is a complex, antidisciplinary problem, it is perhaps unsurprising that much of the most exciting work on the prospects for radical change has been written outside of academia. For example, Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Capitalism Versus the Climate answers our first question—can we conceive of revolution(s) in the name of climate justice, and if so, what do they look like?—affirmatively, arguing that we can overcome the deadlock in the struggle between capitalism and climate justice by building a global movement from “Blockadia”:

Blockadia is not a specific location on a map but rather a roving transnational conflict zone that is cropping up with increasing frequency and intensity wherever extractive projects are attempting to dig and drill, whether for open-pit mines, or gas fracking, or tar sands oil pipelines. What unites these increasingly interconnected pockets of resistance is the sheer ambition of the mining and fossil fuel companies: the fact that in their quest for high-priced commodities and higher-risk “unconventional” fuels, they are pushing relentlessly into countless new territories, regardless of the impact on the local ecology … What unites Blockadia too is the fact the people at the forefront—packing local council meetings, marching in capital cities, being hauled off in police vans, even putting their bodies between the earth-movers and earth—do not look much like your typical activist, nor do the people in one Blockadia site resemble those in another. Rather, they each look like the places where they live, and they look like everyone: the local shop owners, the university professors, the high school students, the grandmothers … Resistance to high-risk extreme extraction is building a global, grassroots, and broad-based network … driven by a desire for a deeper form of democracy, one that provides communities with real control over those resources that are most critical to collective survival—the health of the water, air, and soil. In the process, these place-based stands are stopping real climate crimes in progress. Seeing those successes, as well as the failures of top-down environmentalism, many young people concerned about climate cha...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Notes

- Index