- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

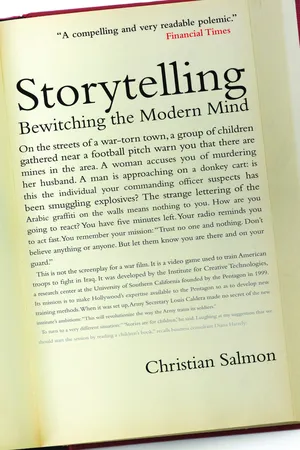

Politics is no longer the art of the possible, but of the fictive. Its aim is not to change the world as it exists, but to affect the way that it is perceived. In Storytelling Christian Salmon looks at the twenty-first century hijacking of creative imagination, anatomizing the timeless human desire for narrative form, and how this desire is abused by the marketing mechanisms that bolster politicians and their products: luxury brands trade on embellished histories, managers tell stories to motivate employees, soldiers in Iraq train on Hollywood-conceived computer games, and spin doctors construct political lives as if they were a folk epic. This "storytelling machine" is masterfully unveiled by Salmon, and is shown to be more effective and insidious as a means of oppression than anything dreamed up by Orwell.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Storytelling by Christian Salmon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1From Logo to Story

In 2000, Canadian journalist Naomi Klein wrote in her book No Logo: “The astronomical growth in the wealth and cultural influence of multinational corporations over the last fifteen years can arguably be traced back to a single, seemingly innocuous idea developed by management theorists in the mid-1980s: that successful corporations must primarily produce brands, as opposed to products.”1 Ten years later, the same theorists had changed their minds; corporations must produce stories, as opposed to brands.

According to Seth Godin, an American innovator in viral marketing, the new marketing is “about telling stories, not selling commercials.”2 And according to Laurence Vincent, the author of Legendary Brands, “Legendary brands are based on narrative construction, and the narrative they tell is the basis of their empathetic consumer affinity.”3 For his part, William Ryan, the man who transformed Apple’s image when the iMac was launched, asserts that we should “Forget traditional positioning and brand-centric approaches. We’re now in the ‘Age of the Narrative’ where the biggest challenge facing companies is how to tell their story in the most compelling, consistent, and credible way possible—both internally and externally.”4

So what happened in the space of ten years? Why does marketing now recommend the brand story rather than the brand image? Have logos lost their aura? How can we explain why the companies we described as postmodern or postindustrial suddenly abandoned the path of branding, which made them so successful in the 1990s, and began to explore the uncharted realm of pre-modern myths and fabulous stories?

The aura of a brand used to come from the product; people who liked the Ford brand drove Ford cars all their lives. Singer owed its prestige to the sewing machine, which was both a piece of furniture and a tool that was handed down from one generation to the next. “By the end of the 1940s,” Naomi Klein writes, “there was a burgeoning awareness that a brand wasn’t just a mascot or a catchphrase or a picture painted on the label of a company’s product; the company as a whole could have a brand identity or a “corporate consciousness,” as this ephemeral quality was termed at the time.”5 By the beginning of the 1980s, General Motors’ advertisements were already telling “stories about the people who drove its cars—the preacher, the pharmacist or the country doctor who, thanks to his trusty GM, arrives ‘at the bedside of a dying child’ just in time ‘to bring it back to life.’ ”6 But the advertising still focused on the product, its uses and its qualities, whereas companies like Nike, Microsoft, and, later, Tommy Hilfiger and Intel were already turning away from products and producing brand-images rather than objects.

Brands in Crisis

Nothing, apparently, had changed at the beginning of the new millennium: the number of brands registered in the United States was constantly increasing (140,000 new trade marks in 2003–100,000 more than in 1983). Big companies were still spending billions of dollars on sponsorship,7 and David Foster Wallace’s joke in his novel Infinite Jest about an America in which corporations would sponsor entire years—the Year of the Whopper, the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment8—no longer seemed far-fetched.

“In the past decade, corporations looking to navigate an ever more competitive marketplace have embraced the gospel of branding with newfound fervor,” wrote James Surowiecki in a demystifying article on “The Decline of Brands” in November 2004:

The brand value of companies like Coca-Cola and IBM is routinely calculated at tens of billions of dollars, and brands had come to be seen as the ultimate long-term asset—economic agents capable of withstanding turbulence and generating profits for decades … Even as companies have spent enormous amounts of time and energy introducing new brands and defending established ones, Americans have become less loyal.9

According to the retail-tracking firm NPD Group, nearly half those who described themselves as highly loyal to a brand were no longer loyal a year later. Because consumers were more promiscuous, established brands were vulnerable, and new ones had a real chance of succeeding. One index of this vulnerability was that the brands that had been the symbol of the multinationals’ prosperity in the 1990s had suddenly lost their prestige and commercial power. Nokia, the brand ranked sixth in the world in 2002, saw its sales collapse the following year and suffered a loss of $6 billion. Krispy Kreme, described as “hottest brand” by Fortune magazine in 2003, and with an estimated value of $30 billion, was dethroned by Atkins in 2004.10 “Paradoxical,” “incomprehensible” and “unpredictable” were the words that marketers have used most often to describe consumer behavior since the beginning of the millennium. “Just ten years ago,” according to the September 18, 2006, issue of the French business paper Les Echos, “socioprofessional categories were enough to identify consumers” habits and even their desires. Alas. The way our modern societies are developing demonstrates the obsolescence of that approach by the day.”11 At the same time, the director of studies for the opinion-polling firm IPSOS stated: “We are addressing consumers who are no longer under the brands’ spell; they have become experts … and that makes them difficult to handle.”12 For his part, Rémy Sansaloni, head of market research and documentation at TNS/Média Intelligence and author of a book entitled The Neo-consumer: How Consumers Are Regaining their Power, took the view that “Consumers are reacting to the anarchic development of pseudo-innovations, promotions right, left and center, and the way mass marketing is standardizing supply, by making themselves scarce.”13

The birth of new media, and the huge opportunities for “viral” advertising opened up by the Internet, have put an end to the unchallenged power of advertising and television. The era of brand advertising is coming to an end. More and more death notices are being posted. According to the authors of the bestselling The Fall of Advertising, “Advertising has lost its power … Advertising has no credit with consumers, who are increasingly sceptical of its claims.”14 And according to former Coca-Cola marketing director Sergio Zyman, writing in 2002, “Advertising, as you know it, is dead … It doesn’t work, it’s a colossal waste of money, and if you don’t wise up it could end up destroying … your brand.”15

Beneath the Swoosh, the Sweatshops

“At the beginning of October 2003, the population of Vienna was intrigued to find that a strange container had taken up residence in one of the city’s main squares,” the Geneva-based newspaper Le Courrier reported on October 31, 2003. The container, which bore the legend “Nikeground. Rethinking Space,” informed the population that the square had been bought by Nike, and that it was therefore going to be renamed “Nikeplatz.” A red swoosh—the stylized comma used as a logo by the sports gear firm—measuring 18 meters by 36—would be flown over Vienna. “Hostesses, all dressed in Nike, explained to visitors that the legendary brand would be present all over Europe: over the next few years, Nikesquares, Nikestreets, Piazzanikes and Nikestraßes would flourish in all the great capitals of the world.”

Nike was forced to react. “This operation is a fraud; we have nothing to do with it. It is a violation of copyright,” explained a spokesperson for the company. It was soon discovered that a mischievous artists’ collective with the unlikely name of 0100101110101101.org was behind the operation. It explained on its website that its goal was to “produce a collective hallucination that could change the way the Viennese saw their city.” Nike’s ire provoked some amused reactions from the impish artists, reported Le Courrier: “ ‘Where is the famous Nike spirit? I expected to be dealing with sportspeople and not a bunch of boring lawyers,’ explained a spokesman for the collective.”16

Nike lodged a complaint and, in a thirty-page document sent to the Austrian Ministry of Justice, demanded the immediate removal of the installations—real and virtual—in the name of brand protection. One is reminded of Naomi Klein’s ironic comment: “Branding … is a balloon economy: it inflates with astonishing rapidity but it is full of hot air. It shouldn’t be surprising that this formula has bred armies of pin-wielding critics, eager to burst the corporate balloon.”17

By the end of the 1990s, anti-brand movements were spreading rapidly. Groups of activists and artists like the “Reclaim the Streets” movement began to challenge the way the brands were taking over public space. The “labeling” of all human activity (commercial and otherwise, economic and cultural), the way humanitarian NGOs and ecological struggles were being commercialized by branding, and the logos’ tyranny over the whole of social life, were met with a wave of increasingly virulent protests. This was a paradoxical phenomenon: the more a brand identified with transgressive value, the more protests it generated. That is what happened to Nike.

From 1995 onwards, in light of many studies carried out in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, public opinion in the industrialized countries began to learn about the working conditions of the men and women who make the divine garments and the flying sneakers. “In China, the vast majority of women workers are paid much less than the legal minimum wage,” the Berne Declaration (a Swiss NGO campaigning for fair trade) stated in 2002. “On average, they work twelve hours a day and up to seven days a week, in violation of both Chinese legislation and Nike’s code. The situation is similar in Vietnam and Indonesia.”18

Growing numbers of NGO campaigns in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe described working conditions in these sweatshops. In California, Nike was taken to court and charged with misleading advertising. Michael Moore’s film The Big One, in which Nike’s Chairman and CEO Phillip Knight justifies the child labor of fourteen-year-olds, had a devastating effect on the swoosh brand. Speaking in Brussels at a conference on the growing power of anti-corporate groups, Peter Verhille of the PR firm Entente International admitted that “one of the major strengths of the pressure groups … is their ability to exploit the instruments of the telecommunications revolution. Their agile use of global tools such as the Internet reduces the advantage that corporate budgets once provided.”19

The anti-Nike movement’s campaigns were revealing globalization’s black holes: they shed light on the invisible links between the brands and their sub-contractors, between the marketing agencies and the underground workshops, between the footballs used by the athletes at the 2008 World Cup and the hands of the children who made them. Beneath Nike’s swoosh, the sweatshops. On May 12, 1998, Phillip Knight told a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington that the company was taking initiatives “to further improve factory working conditions worldwide and provide increased opportunities for people who manufacture Nike products,” and admitted that Nike had become “synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime, and arbitrary abuse.”20

These measures could, at best, put an end to the scandal of the sweatshops. Was Nike about to commit itself to a new labor policy? But would that be enough to restore the brand’s magic, or at least to appear to do so? The reason why demonstrations and artistic performances had succeeded in undermining Nike’s swoosh was that the image was no longer enough. The brand had to be based upon something less volatile than a slogan, an elegant logo, or an eye-catching commercial.

What’s in a Name?

Theorists of branding were summoned to the brand’s bedside. MTV’s founder Tom Freston had already issued a warning in 1998: “You can beat a brand to death.”21 Everyone was agreed about one thing: brands were sick. Serious questions were being asked about their future: “It can take 100 years to build up a good brand and 30 days to knock it down,” complained John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance president in January 1999.22 Branding evangelist Tom Peters wondered: “How much is enough? Nobody knows for sure. It’s pure art. Leverage is good. Too much leverage is bad.”23 Kevin Roberts, CEO of the Saatchi and Saatchi advertising agency and author of Lovemarks agreed: “Brands have run out of juice. They’re dead.”24

Nike was a victim of its own excessive fame, and Wall Street commented that it had “outswooshed itself.”25 So can a brand’s fame plateau, and then begin to depreciate and lose its influence? According to James Surowiecki, brands do indeed wear out: “They’re becoming nothing more than shadows. You wouldn’t expect your shadow to protect you or show you the way.”26 The firms decided to go back to basics. The role of marketing is to sell, and that objective can be obtained in various different ways: through aggressive advertising or material inducements, directly or indirectly with advertisements that have a subliminal influence, but also by involving the consumer in a long-term emotional relationship. That is the brand’s role: to “involve” the consumer. That is why brands are effective, and why they are mysterious.

In the famous passage on commodity fetishism in Capital, Marx writes: “If commodities could speak, they would say this: our use-value may interest men, but it does not belong to us as objects. What does belong to us as objects, however, is our value.”27 What was for Marx no more than a rhetorical hypothesis has become a reality: brands have begun to speak. And “when these brands speak, consumers listen intently. When these brands act, consumers follow … These brands are not just marketing constructs: they are figures in the consumer’s life.”28

In the 1990s, brands began to express themselves through dazzling logos—Apple’s apple, Nike’s swoosh, the oil company’s shell, McDonald’s golden arches—and all kinds of pictograms. The product was dissolved into the brand. Within a decade, the logo, even more so than money, had become the sign of wealth. And the brand became a pure value that shimmered in the sky of the stock exchanges. James Suroweicki made the point that

Marketers aren’t completely deceived (or being deceiving) when they argue that consumers make emotional bonds with brands, but those connections are increasingly tenuous … Gurus talk about building an image to create a halo over a company’s products. But these days, the only sure way to keep a brand strong is to keep on wheeling out new products, which will in turn cast the halo. (The iPod has made a lot more people interested in Apple than Apple made people interested in the iPod).29

“What’s in a name?” asked Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet. “That which we call a rose/By any other name would smell as sweet.” Ashraf Ramzy—a marketing consultant whose clients include Nissan, Canon, and KLM—and Alicia Korten asked the same questi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to the English-Language Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Magic of Narrative, or, the Art of Telling Stories

- 1. From Logo to Story

- 2. The Invention of Storytelling Management

- 3. The New “Fiction Economy”

- 4. The Mutant Companies of New-Age Capitalism

- 5. Turning Politics Into a Story

- 6. Telling War Stories

- 7. The Propaganda Empire

- Afterword: Obama in Fabula

- Notes