- 544 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

My First Life

About this book

Hugo Ch?vez, military officer turned left-wing revolutionary, was one of the most important Latin American leaders of the twenty-first century. This book tells the story of his life up to his election as president in 1998.

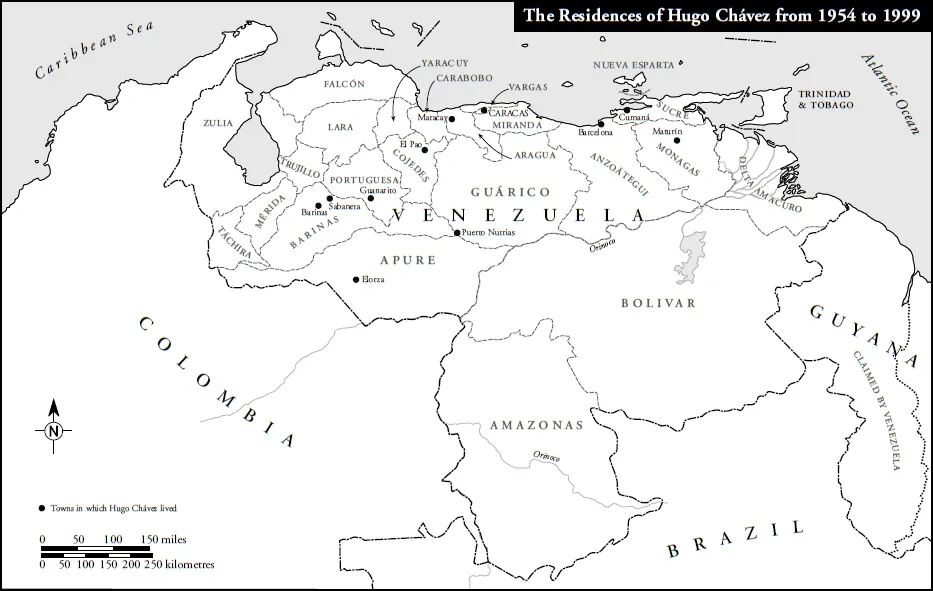

Throughout this riveting and historically important account of his early years, Ch?vez's energy and charisma shine through. As a young man, he awakens gradually to the reality of his country-where huge inequalities persist and the majority of citizens live in indescribable poverty-and decides to act. He gives a fascinating description of growing up in Barinas, his years in the Military Academy, his long-planned military conspiracy-the most significant in the history of Venezuela and perhaps of Latin America-which led to his unsuccessful coup attempt of 1992, and eventually to his popular electoral victory in 1998.

His collaborator on this book is Ignacio Ramonet, the famous French journalist (and editor for many years of Le Monde diplomatique), who undertook a similar task with Fidel Castro (Fidel Castro: My Life).

Throughout this riveting and historically important account of his early years, Ch?vez's energy and charisma shine through. As a young man, he awakens gradually to the reality of his country-where huge inequalities persist and the majority of citizens live in indescribable poverty-and decides to act. He gives a fascinating description of growing up in Barinas, his years in the Military Academy, his long-planned military conspiracy-the most significant in the history of Venezuela and perhaps of Latin America-which led to his unsuccessful coup attempt of 1992, and eventually to his popular electoral victory in 1998.

His collaborator on this book is Ignacio Ramonet, the famous French journalist (and editor for many years of Le Monde diplomatique), who undertook a similar task with Fidel Castro (Fidel Castro: My Life).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

CHILDHOOD

AND ADOLESCENCE

(1954–1971)

1

‘History will absorb me’

28 July 1954 – Historical context – Uslar Pietri

The Third World rises – The Cold War

Dictators in Latin America – Sabaneta – El Boconó

Los Llanos, ‘magic land’ – Being a llanero – Anecdotes

Anti-Indian racism – Grandmother Rosa Inés – Black blood

Christ, the first revolutionary

The Third World rises – The Cold War

Dictators in Latin America – Sabaneta – El Boconó

Los Llanos, ‘magic land’ – Being a llanero – Anecdotes

Anti-Indian racism – Grandmother Rosa Inés – Black blood

Christ, the first revolutionary

Mr President, you were born on 28 July 1954, in a historical context which saw the birth of the so-called Third World and the beginning of the end of colonialism. I’d like to look back at a few other important dates around that time. Almost exactly a year earlier, on 26 July 1953, Fidel Castro led the attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba. And a month before your birth, on 27 June 1954, there was a coup d’état against Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala. Almost a month after that, on 15 August 1954, Alfredo Stroessner’s dictatorship took power in Paraguay. This was followed, on 24 August, by the coup d’état in Brazil and the suicide of Getulio Vargas. A few months earlier, on 7 May 1954, the French Army surrendered at Dien Bien Phu, Indochina. And just a few days before your birth, the war in Indochina ended in victory for the newly decolonized country of Vietnam. A few months later, however, on 1 November 1954, war would break out in Algeria. And we were only a year away from the famous Bandung Conference which heralded the concept of the Third World and Non-aligned Countries.

So, there was a discernible political and historical context in which one period died and another was born. And you, too, were born. What inspires you about this constellation of events surrounding the date of your birth?

Yes, I came into the world in this historical context, that’s true. The morning I was born was, I believe, the day Fidel Castro planned his escape from the Modelo prison on the Isle of Pines. Lots of things were happening all around the world. We were just halfway through the twentieth century. And when you list all those events, you’re talking about real history. That naturally leaves its mark. Our lives are influenced and determined by the conditions into which we are born, the circumstances we grow up in. Marx said, ‘Men make history with the conditions reality imposes on them.’ I realized this as I went through life, and from reading Marc Bloch.

A great French historian, a member of the anti-Fascist resistance. He was Jewish and was shot by the Nazis in 1944. A huge intellect.

I admire him very much. I’ve had his short book The Historian’s Craft beside me for a long time.1 Between adolescence and maturity, at the stage you start to become aware of life, I used to ask myself, as Marc Bloch does, ‘What is the use of history?’ History can arouse your curiosity, and it can also be a seductive narrative. Because the spectacle of human activity is seductive. And Bloch classifies actions as ‘historical’ or ‘unhistorical’. Seeking a more exact definition of history and asking himself what use it is, he says ‘History is like the ogre in fairy tales; wherever he smells meat, there lies his prey.’ Because the object of history is mankind, human beings.

Of course, we come into the world an empty vessel, born like a calf on these plains, like a cristofué in the branches of those trees.2 Unconscious. But then, slowly we become aware, we acquire consciousness. Or not. In my case – with a nod to Fidel’s famous phrase ‘History will absolve me’ – if as a boy I had thought about history and life, if I’d been aware, I might have said, ‘History will absorb me.’3

You plunged into history, like Achilles into the River Scamander or Siegfried in the dragon’s blood …

Thinking ‘history will absorb me’ was simply intuitive on my part. I am, as Bloch says, human flesh. I was dragged along by the ogre of history and torn to pieces by him. The teeth of history, or – not to make history aggressive or malevolent – the arms of history enveloped me, the hurricane of history swept me up. Bolívar said, ‘I am a mere wisp of straw swept up by the force of a hurricane.’ I am submerged in a hurricane, or an invisible river. I see that history in the wind of the Llanos, in the breeze that sways the trees, in the heat of this savannah, I touch it, feel it. Because into that history, I was born.

Arturo Uslar Pietri said, ‘The Venezuelan is thirsty for history.’ Do you share that idea?

Yes, I think I do. Uslar was upper-class – you knew him, I think – but he was a great patriot.4 He wrote the novel The Red Lances, about the exploits of the llaneros, the men of the Venezuelan plains, and Robinson’s Island, a marvellous novel about Simón Rodríguez.5

Dr Uslar Pietri was a highly respected man, and is greatly missed. In the 1940s, when General Isaías Medina Angarita was in power, he talked about the need to ‘sow oil’.6 I knew him too, first because I used to read a lot, and then after our uprising of 4 February 1992, when I was in jail, there was speculation about its ‘intellectual authors’, as if we couldn’t think for ourselves. And they tried to implicate Uslar. It’s true he made a few statements justifying our action, and they raided his house.7 So, after that, Uslar opposed the government of Carlos Andrés Pérez even more fiercely, and declared, ‘I said it was going to rain … and it rained.’8

Two years later, in 1994, when I came out of prison, I contacted him and he invited me to his house in the Caracas suburb of La Florida. He received me in his library and we talked for a long time. He was recently widowed. I’ll never forget what he said when I asked him why he was no longer writing the column he’d had in El Nacional for fifty years. He replied, ‘You know, Commander, you have to leave before they throw you out.’

He had light blue eyes and a hoarse, warmly modulated voice. The tone of his voice, the clarity with which he spoke and the way he expressed himself made an enormous impression on me. I was bowled over. I had seen him on television; he had a weekly programme on Radio Caracas Televisión called Human Value which was excellent. Personally I was moved by his intelligence and the warmth with which he received me. I remember him saying, ‘Comandante, life is like a play, some actors are at the front of the stage, others stand at the back; some write plays, others direct them; and others are spectators. When you’re a theatre actor, you have to be careful at two particular moments: when you come on stage and when you exit.’ He added, ‘I watched you come on with a red beret and a gun, now it’s up to you how you get off.’

What was that phrase he told you?

‘The Venezuelan is thirsty for history.’

I think Arturo Uslar Pietri summed up the essence of Venezuela in a nutshell; there is enormous truth in that phrase. He wasn’t talking about an individual but about the Venezuelan people as a whole. And it is that thirst that they have been partially able to quench in the last few years, after a long drought. They have found a source, a spring. The Bolivarian Revolution has given Venezuelans back their history. They were thirsty for a Patria, and that thirst has been quenched.

I myself began gorging on history a long time ago. Probably looking for the key to our future. It was Heidegger who said, ‘There is nothing so full of the future as the past.’9

And when did you become aware that the reality enveloping you was the product of history?

What was happening at that particular moment of the century I was born into? More or less what you were saying before, except I wouldn’t say that I came into the world when the Third World was being born, because the Third World already existed, though it wasn’t called that then. So perhaps what was emerging was the awareness that a Third World existed, don’t you think?

Yes, the concept of the Third World emerged at that time. The French economist Alfred Sauvy gave it to us in 1952. Just as before the French Revolution in 1789, there were three social categories in France: the aristocracy, the clergy or Church, and ordinary people. Using this model, Sauvy says that, during the Cold War, there was a First World – the capitalist world; a Second World – the Communist one; and a Third World which was neither capitalist nor communist but a ‘colonized, exploited and despised, world’. But then, at the Bandung Conference in 1955, when, as you said, a political awareness of developing countries emerged, the press referred to them collectively as the Third World. Just as 500 years earlier they called us the New World.

That’s right.

There was no first, second or third then, just two worlds: the Old World was Europe and the New, which appeared in 1492, was the New World. Then this idea of the Third World emerged. When I was born, of course, we were already halfway through the century; the Soviet Union was already forty years old. And Mao Zedong’s China was five.

The era of the Cold War.

The Communist camp had come into being; the Soviet Union and all its allies. We now had a bi-polar world dominated by two hegemonies: the United States and the Soviet Union. The Second World War had been over for almost a decade, the conflicts in Vietnam and Algeria had started, as well as many other less chronicled wars in Africa and Latin America. You talked about coups d’état: Juan Domingo Perón was ousted by a coup in Argentina about then.10

September 1955, to be exact.

Who ousted Perón? The United States. By the time I was born, the Americans had bombed Guatemala, and were engaged in a fullblown invasion of that country.

You’d arrived one month earlier, on 27 June 1954. Jacobo Árbenz had already been forced into exile …11

That’s right. The US invaded Guatemala, toppled Perón, overthrew Juan Bosch,12 backed a coup in Brazil13 … A few years before that, in October 1948, they had supported a coup d’état in Peru led by General Manuel Odría.14 And even before that, on 9 April 1948, they had assassinated Jorge Eliécer Gaitán in Bogotá.15 Imagine, six years before I was born, they had killed Gaitán, right on our doorstep in Colombia. That caused the Bogotazo, and started the conflict that is destroying Colombia to this day and affecting several other South American countries. Coincidentally, our friend Fidel Castro actually witnessed the assassination of Gaitán and the Bogotazo.16

We’re talking about hugely significant events all over Latin America: Guatemala, the Caribbean, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, Stroessner’s dictatorship in Paraguay, and here in Venezuela, by 1954, the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship was in full swing.17

And actually, four years earlier in Venezuela, in November 1950, they had also assassinated Colonel Carlos Delgado Chalbaud, a progressive army officer who had studied in France. He was the son of the political leader Román Delgado Chalbaud, former head of the Venezuelan Navy, who had spent fourteen years in jail during the long dictatorship of Juan Vicente Gómez.18 Gómez eventually released him and he went to France to be reunited with his young son, Carlos, who had been sent there while his father was in jail. Carlos Delgado Chalbaud studied in France, graduated as an engineer and married a French student called Lucía Devine, an active member of the French Communist Party. He returned to Venezuela after Gómez’s death in 1935 and, even though he was an engineer, he joined the army. He was a man of great prestige. When the gringos got rid of President Rómulo Gallegos, author of that brilliant novel Doña Bárbara, in November 1948 …19

Rómulo Gallegos was from this region, the Llanos, wasn’t he?

No, Gallegos was from Caracas, but he based Doña Bárbara on the history, geography and myths of the Llanos. It’s interesting to note that Doña Bárbara is the quintessential Venezuelan novel, doubtless because of the writer’s enormous talent, but also because the Llanos are the essence of Venezuela. In this boundless savannah, in the freewheeling winds that caress it, in its audacious nature and in its indomitable people, lies the very heart of Venezuelan identity.

That would be what attracted Gallegos. You were saying that they ousted him as well …

Yes, Rómulo Gallegos was overthrown on 24 November 1948. I met a man who worked with him in the presidential palace. He died ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: One Hundred Years with Chávez by Ignacio Ramonet

- Part I: Childhood and Adolescence (1954–1971)

- Part II: From Barracks to Barracks (1971–1982)

- Part III: The Road to Power (1982–1998)

- Notes

- Acknowledgements and Further Reading

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access My First Life by Ignacio Ramonet,Hugo Chávez, Ann Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Biographies politiques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.