- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

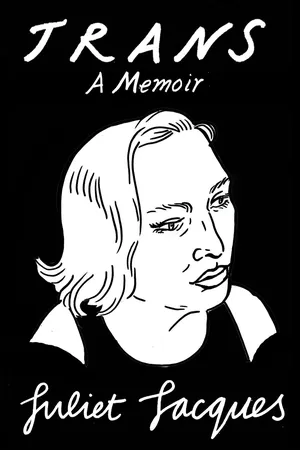

In July 2012, aged thirty, Juliet Jacques underwent sex reassignment surgery-a process she chronicled with unflinching honesty in a serialised national newspaper column. Trans tells of her life to the present moment: a story of growing up, of defining yourself, and of the rapidly changing world of gender politics. Fresh from university, eager to escape a dead-end job and launch a career as a writer, she navigates the treacherous waters of a world where, even in the liberal and feminist media, transgender identities go unacknowledged, misunderstood or worse. Revealing, honest,humorous, and self-deprecating, Trans includes an epilogue with Sheila Heti, author of How Should a Person Be?

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Transgender Journey

Six weeks before sex reassignment surgery (SRS), I am obliged to stop taking my hormones. I suddenly feel very differently about my forthcoming operation. I’d previously seen transition as a marathon: surgery was like breaking the tape, but the race was won far earlier. Now I reconsider: perhaps this is more like a difficult cup final after some hard previous rounds.

It consumes my conversations as it inches closer. I am constantly asked how I feel: everyone expects a mixture of excited and nervous, and they are right. Above all, I’ll be glad when it is over.

I take a little holiday in late June 2012, staying with friends in Scotland, and travel back on the first day of July. Then, for the next fortnight, my concerns over the practical, physical and psychological effects of SRS intensify by the day.

My psychotherapist, whom I’ve been seeing all year, tells me that I’ve barely touched on the surgery, so I devote my final pre-surgical appointment to it. After an hour of airing my anxieties, I feel calm and able to continue.

Five days before checking into hospital, I sign off. Returning from the Jobcentre, a man with a taste for ‘shemales’ (his word) follows me home, making me feel far less secure in my house – my sanctuary in a life that has felt in constant chaos. I break down in tears, crying for thirty years of feeling like an outsider, twenty years of knowing this to be related to my gender, ten years of exploring it, three years of transition and two years of writing about it, with all their stresses and traumas simultaneously hurtling to the fore.

For four days, everything makes me weep. At first it’s painful, then cathartic, and finally just annoying – having not cried when I expected to for years, the sight of every ornament, every poster in my house sets me off, and I don’t know when it’ll stop. Eventually, I realise I need to get out: I visit old friends in Brighton, who indulge me as I discourse about the run-up to surgery and my feelings about it.

I return a day before admission: having to address the practicalities pulls me together, as I ensure I have everything I’ll want or need during the seven-day stay. I’ve never been seriously ill or injured, so I’ve sought advice on what to take: I buy slippers and a crossword book. Once I’ve got everything on my list, and packed, I feel completely relaxed. I go to bed content, close my eyes, and then see a car crash outside my bedroom window. It’s so vivid, it takes several moments to realise that the flaming wreckage is no more than the invention of my hyperactive subconscious, but once I do, I get a solid night’s sleep – my last for some time.

Obsessed with being brave and independent, I’d travelled alone to my previous surgical appointments. This time, on advice, I’ve arranged for my friend Tania Glyde to take me to hospital. She arrives around midday: we eat in my favourite café and then get the Tube to Hammersmith, well before I have to report to Charing Cross hospital reception at 4 p.m. We say little, putting our arms round each other, but once I’ve checked in, she gives me some earplugs and a cuddly tiger (‘You’ll need a soft toy, trust me’). Then she goes, telling me to surrender myself to the nurses, and I find my bed in F bay on the Marjorie Warren ward.

There are six beds, with most but not all occupants also undergoing SRS. Reassuringly, there are two people who had surgery a day before, who can hold conversations and move unaided. We chat before the nurses take my weight and blood pressure, measuring me for stockings to fight deep vein thrombosis as I’ll be spending so long in bed. I order dinner and then sleep, struggling more with the sweltering temperature than anything else.

At 5:30 a.m. I’m woken for an enema: they have to thoroughly clear my bowels before the procedure. It’s not pretty but I take it, shower and return to bed. At 7 a.m. the surgeon enters with two consent forms – one for the hospital, the other for me. He asks if I will allow the ‘tissue removed’ to be used for medical science. In the hazy half-light, I agree (to the disappointment, I imagine, of friends who’ve asked if they can have it). ‘I’ll see you soon,’ the surgeon says. The anaesthetist comes soon after and asks several questions before I lie back down.

At 8:20 a.m. I’m escorted upstairs. I take the lift to the fifteenth floor in my slippers, white hospital gown and navy stockings. The chattering voices in my head silence themselves, with just the closing bars of Laurie Anderson’s O Superman soaring through my mind, and I am ready.

Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha, ha …

Yuri, who assists the anaesthetist, lays me on a trolley and takes my blood pressure and temperature. The anaesthetist enters, attaching a cannula to my right wrist. She asks if I have any questions. ‘This’ll definitely work, right?’ Yes, she says, irked. ‘It’s just that I studied nineteenth-century medicine,’ I say. ‘It didn’t fill me with confidence.’

‘It’ll be fine,’ she says, raising a needle. ‘You may feel a shooting sensation in your arm …’

I wake in the recovery room, dehydrated, my lips bone dry. I demand water, but it’s nil by mouth until I return to the ward. I’m slow to come round, though, and they won’t move me until I’m fully awake, however much I ask. After what seems an age, – I’ve no idea how long – they wheel my bed into the lift, and then back to F bay.

The women there are glad to see me back: I tell them that it went well, before finding a wave of ‘good luck’ messages on my phone. I go on Twitter to say that I’m conscious again; throughout my stay, social media keeps me sane, providing contact with friends, family and well-wishers at any time, saving dozens of energy-sapping conversations.

The nurses set up intravenous morphine, which goes towards compensating for the hated catheter bag strapped to my thigh. The machine bleeps whenever morphine is administered, which is not every time I press it, and it does bizarre things to my sleep: I close my eyes for what feels like several hours, only to find it’s been five minute; but I get through the night. Dizzy and nauseous, I try not to be tetchy with the nurses, who do their best, but I struggle with the shared ward, wanting my own space and getting annoyed when they open the curtains without asking, feeling guilty about occupying myself with my headphones although everyone else is perfectly understanding.

One day after the operation, the morphine is removed. The nurses say it’s to stop me getting addicted: I argue, unsuccessfully, that we can cross that bridge when we come to it. It’s replaced by paracetamol and ibuprofen, which doesn’t always shift a headache, and proves woefully inadequate. With vaginal packing to keep me open, I’m in severe discomfort: the lights go out at 10 p.m. and, laid flat on the hard mattress, as resting on my side impossible for the foreseeable future, I cannot sleep; the excess light, sound and heat driving me crazy.

At 3:30 a.m. I ring for the nurse. She comes, and I beg for sleeping pills, or stronger painkillers. I needed to ask earlier for pills as they have to be prescribed, and I’ve had my allotted pain relief, so there’s nothing she can do. I ask when the packing comes out. ‘Monday’, she says, which I repeat in disbelief: it sounds an eternity. Then she leaves. Trying not to scream, convinced that no operation could ever be worth this level of pain and cursing myself for signing up, my outlet is Twitter. I post that this is the worst night of my life, and that I feel like I may never sleep again, and a handful of kind responses from insomniac friends and transatlantic contacts give me a little cheer.

At 6:30 a.m. I fall asleep. I wake an hour later to find nothing has changed, and it feels like this night will last forever. A nurse enters to take my blood pressure and I start crying, having promised myself I wouldn’t, for the loss of independence, privacy and dignity, symbolised by the hospital staff changing me like a baby. ‘You surrender those when you walk in, I’m afraid,’ she says: harsh as it sounds, the reminder that these feelings are to be expected provides comfort, and night eventually rolls into day, clearly demarcated by the nurses turning on the lights, opening the curtains and offering breakfast.

The nurse specialist comes to check the wound, removing the pad over it. I look down and start hyperventilating: it’s encircled by heavy bruising, the pad splattered in blood and pus. She insists I tell her what’s wrong: I say it’s discombobulating and looks disgusting. Worse, there’s a ‘phantom limb’ sensation, as I think I can feel the old organ moving in the itchy cloth underwear like it used to, even though I know it’s gone. Psychologically it’s unbearable. This will pass, she says; there are no complications, so all will heal.

My old friend Joe Stretch is coming down from Manchester to visit. With time passing so slowly, the prospect of his company keeps me going: I text to say that as he’s coming before dedicated visiting hours, he must meet me in the day room, and that as I’ve not slept and am in absolute agony, I won’t be at my best. Even though it hurts to laugh, his reply is perfect: ‘Stop moaning! It’s probably just a cold!’

At 10 a.m. he arrives and I shuffle to the day room, moving like a toddler who’s learned to walk by watching John Wayne films. Gently, he hugs me, and we sit. I take the sofa as I need to stretch my legs out, and talk him through everything from leaving my house to the present. I keep stopping, holding my forehead as the physical and psychological pains engulf me, but after an hour, I’m done. I pause, then ask: ‘Anyway, how are things with you?’

We laugh, but I insist he tells me: other people’s lives reintroduce normality, and discussing our usual subjects becomes really important. To make myself feel more human, I’ve put on makeup. We joke about the contrast between that and my ‘sexy’ catheter.

Feeling less tired and looking better than I’d expected, I change my pads and empty the catheter myself, passing time by watching Georges Méliès films and Paul Merton’s programme on Buster Keaton on my laptop. Billie, who’s had her operation days earlier, introduces herself. We click, sharing a love of sport, political theatre and literature; she looks at my books, and I tell her that the only one I can handle is a favourite volume of poetry, Jacques Prévert’s Paroles. She’s intrigued, and suddenly, in this rarefied environment, there’s an unanticipated moment of beauty. She sits, takes my hand and reads:

To Paint the Portrait of a Bird

First paint a cage

with an open door

then paint

something pretty

something simple

something beautiful

something useful

for the bird

then place the canvas against a tree

in a garden

in a wood

or in a forest

hide behind the tree

without speaking

without moving …

Before she even finishes this beautiful little poem we’re firm friends, swiftly united in subverting our routine as much as possible. Just as the nurses are putting everyone to bed, she sneaks in and disconnects my catheter from the night bag so we can go and watch GB’s Olympic football team play Brazil. The match is uncompetitive, sterile and meaningless but here, all the aspects of the BBC’s football coverage that usually induce apoplexy, particularly Garth Crooks’s endless banalities, are strangely soothing, and I go to bed far happier than when I rose, having requested sleeping pills well in advance.

I sleep deeply for four hours, then wake, fixated upon the question of inequality. Gradually realising that I’m in no fit state to resolve this longstanding problem, it takes time to settle back down. I take them again the following night, and something similar happens: I rise with this singular sensation of disconnect from my body. At 3:30 a.m. I go to the day room to read. Billie joins me and we watch more football together.

Soon I weep again, through tiredness and pain. I venture out into the garden for the first time. Just seeing London life – a tower block, a single car and a pedestrian – makes me realise that soon I’ll be out, with the pain subsiding, and this and the fresh air makes me feel infinitely better.

That night I meet Katya, who’ll be having her operation tomorrow, and I tell her that although she’ll be sore, she’ll be fine if she asks for sleeping pills and gets friends to sneak in food, and that the joy at resolving her gender dysphoria will make it all worthwhile, as it has for me.

As soon as I wake on Monday, I ask the nurse when the packing and the catheter will be removed. ‘After breakfast,’ she replies. Suddenly, I’ve never wanted tea, toast and cereal so much. When it comes, I eat voraciously, impatient for her to return. Eventually, she does: the removal is traumatic, taking longer than anticipated, and seeing the blood-soaked gauze makes me hyperventilate again. She calms me by saying I can shower and wash my hair, and that if I relieve myself efficiently, I’ll be discharged tomorrow. Later, I manage to pee: it goes everywhere, but that’ll fix itself, and the discomfort is outweighed by knowing that I’m a massive step closer to leaving. My morale is boosted further as I put on my own clothes.

I start dilating, using lubricating jelly and two five-inch dilators, one two inches wide, the other three. I have to use the smaller one for five minutes, then the larger for twenty to keep the neovagina open, three times daily for now. (In Scotland I met someone who was down to once a month, three years post-SRS.) This is very dull, and I make it tolerable by listening to music. It goes fine, so there’s just one final barrier to my exit: I need to open my bowels. On Monday night, after I’ve ducked across the road for takeaway pizza – the first time I’ve left the hospital grounds – the nurse gives me laxatives, and I prepare for the most important dump of my life.

You don’t need me to describe this – I couldn’t top the toilet scene in Ulysses and even if you’ve not read it, you know what it’s like – but later I triumphantly tell the nurses that I’ve done the business, and they say I can go now if I wish. I call my parents, my housemate Helen and others, deciding not to leave in a rush. This proves wise as the nurse specialist, who’s not back until morning, must see me dilate. She’s satisfied that I do it properly, and now the only thing keeping me is the wait for the pharmacy to send my medication. Helen comes to help me home: I’m overjoyed to see her, and we chat for an hour before my painkillers and taxi arrive.

When the car pulls up at my house I drag my suitcases inside before collapsing on to my bed, overwhelmed by the simple pleasure of seeing my own home.

Guardian, Thursday, 30 August 2012

2

September 2000. I opened the little purse, given to me by a friend at Collyer’s, my sixth-form college in Horsham, which held my makeup. The black mascara came from Superdrug; I’d been too nervous to take it to the counter myself, so Jennie had done it for me. When the cashier told her it would look good on her, Jennie laughed and replied, ‘It’s for him.’ Liquid foundation, on offer at Boots, which I bought after Jennie helped me realise the world wouldn’t end if the shop assistant knew I’d wear it. Glittery eye shadow, a birthday present from Corinne, who’d sat next to me when the register was taken. She’d seen the pictures of transsexual punk singer Jayne County and Manic Street Preachers lyricist Richey Edwards – in his leopard-print blouse and eyeliner – in my ring binder and asked who they were. When I explained, she told me how she loved Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, the Australian movie about a transsexual woman, a transvestite and a drag queen who toured their cabaret act across the outback. After I told her that I was ‘gay’ and ‘a cross-dresser’, she gave me her old tops, shoes and cosmetics.

At least I don’t have to hide this from my parents any more, I thought as I stood at the mirror in my room in Oak House, one of the biggest (and cheapest) student halls in Fallowfield, the university district in south Manchester. I shaved my face for the second time that day and then rubbed on the foundation. Would blusher be too much? I wondered as I put more gel into my short, spiky hair. I decided to do just my eyes, and that I’d stick with my Joy Division T-shirt, denim jeans and DM boots. What did people wear to these places anyway?

I met Lynne and Lauren, who lived...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- Epilogue

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Trans by Juliet Jacques in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.