- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

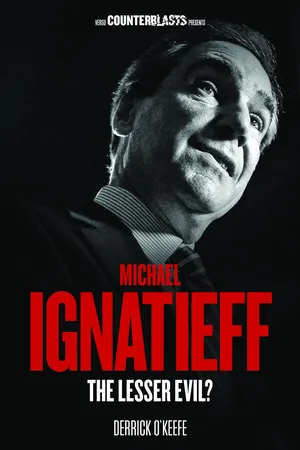

One of the most influential intellectuals in the English-speaking world, Michael Ignatieff's story is generally understood to be that of an ambitious, accomplished progressive politician and writer, whose work and thought fit within an enlightened political tradition valuing human rights and diversity. Here, journalist Derrick O'Keefe argues otherwise. In this scrupulous assessment of Ignatieff's life and politics, he reveals that Ignatieff's human rights discourse has served to mask his identification with political and economic elites.

Tracing the course of his career over the last thirty years, from his involvement with the battles between Thatcher and the coal miners in the 1980s to the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Israel's 2009 invasion of Gaza, O'Keefe proposes that Ignatieff and his political tradition have in fact stood in opposition to the extension of democracy and the pursuit of economic equality. Michael Ignatieff: The Lesser Evil? is a timely assessment of the Ignatieff phenomenon, and of what it tells us about the politics of the English-speaking West today.

About the series: Counterblasts is a new Verso series that aims to revive the tradition of polemical writing inaugurated by Puritan and leveller pamphleteers in the seventeenth century, when in the words of one of them, Gerard Winstanley, the old world was "running up like parchment in the fire." From 1640 to 1663, a leading bookseller and publisher, George Thomason, recorded that his collection alone contained over twenty thousand pamphlets. Such polemics reappeared both before and during the French, Russian, Chinese and Cuban revolutions of the last century. In a period of conformity where politicians, media barons and their ideological hirelings rarely challenge the basis of existing society, it's time to revive the tradition. Verso's Counterblasts will challenge the apologists of Empire and Capital.

Tracing the course of his career over the last thirty years, from his involvement with the battles between Thatcher and the coal miners in the 1980s to the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Israel's 2009 invasion of Gaza, O'Keefe proposes that Ignatieff and his political tradition have in fact stood in opposition to the extension of democracy and the pursuit of economic equality. Michael Ignatieff: The Lesser Evil? is a timely assessment of the Ignatieff phenomenon, and of what it tells us about the politics of the English-speaking West today.

About the series: Counterblasts is a new Verso series that aims to revive the tradition of polemical writing inaugurated by Puritan and leveller pamphleteers in the seventeenth century, when in the words of one of them, Gerard Winstanley, the old world was "running up like parchment in the fire." From 1640 to 1663, a leading bookseller and publisher, George Thomason, recorded that his collection alone contained over twenty thousand pamphlets. Such polemics reappeared both before and during the French, Russian, Chinese and Cuban revolutions of the last century. In a period of conformity where politicians, media barons and their ideological hirelings rarely challenge the basis of existing society, it's time to revive the tradition. Verso's Counterblasts will challenge the apologists of Empire and Capital.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 THE SOLIPSISTIC COSMOPOLITAN

A country begins to die when people think life is elsewhere and begin to leave.—Michael Ignatieff, True Patriot Love

Born on third, thinks he got a triple—Pearl Jam, “Bushleaguer”

Al Capone, notorious underworld boss of America’s “second city,” famously shrugged off North America’s “second country” with pithy indifference: “I don’t even know what street Canada is on.” In the years since, unfortunately, the True North has earned similar contempt from ostensibly more enlightened sources. British historian Eric Hobsbawm once dismissed Canada as “culturally provincial, though interesting things and people occasionally emerge from it”1. Ken Kesey, the late American author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, expressed a similar lack of interest in all things Canadian. An icon of the counter-culture and self-described link between the Beatniks and the hippies, Kesey’s open mind couldn’t take in the giant country just to his north. He assessed the prospects for the advent of the “New Consciousness”: “Europe was too stiff to bring it off, Africa too primitive, China too poor. And the Russians thought they had already accomplished it. But Canada? Canada had never even been considered.”2

Although they were not in search of the new consciousness, the Ignatieff household of the 1960s appears to have shared a similar mental map. In his 2009 book True Patriot Love: Four Generations in Search of Canada, a literary project admittedly dusted off to bolster his Canadian bona fides, Ignatieff recalls a little ditty his mother used to sing around the house in the sleepy capital city of Ottawa.

I grew up in a Canadian household where my parents did think that life was elsewhere. This is how it is in small countries and provincial societies everywhere in the world. My mother used to go around the house humming a Judy Garland song with a line about how, if you haven’t played the Palace, you might as well be dead. The Palace Theatre was elsewhere—not in Ottawa, where I grew up, but in the big bright world beyond. So the family question wormed its way into how I thought of my life, and the answer I gave myself was to get out of here, to go out into the bright world beyond and play the palace. (TPL, p. 28)

The real testing ground of his life lay elsewhere. So off he went. It would appear that in the young Michael’s mind a precocious certainty emerged that he would be one of those rare noteworthies to come from Canada, and that meant hightailing it out of his mediocre homeland. He reports back proudly, “I played the palace in London for twenty years, as a journalist and writer, and for five years at Harvard as a professor.”

This confession in the opening pages of True Patriot Love would seem to be an effort to tackle head-on the obvious tension between Ignatieff’s wandering CV—over 30 years outside of Canada—and his newly asserted political aspirations in his homeland. For much of his adult life, Ignatieff led a highly self-conscious “cosmopolitan” existence, going so far as to deny the need for a home country at all. He seemed to take pleasure in “re-inventing” himself and “making it up as he [went] along,” from affecting the speech of the British to adopting the militarist zeal of American neo-conservatives. Nevertheless, returning to Canada as he approached his 60th birthday, Ignatieff became a born-again patriot. The wide-ranging circle of his life would prove difficult to square with the requirements of Canadian electoral politics. Even given the usually forgiving, soft-nationalist, and often insecure Canadian psyche, it would prove difficult for Ignatieff to overcome the impression that he was a Nowhere Man—the quintessential carpetbagger opportunist.

As the son of a diplomat, it’s not surprising that he has led an itinerant life. Weeks after Michael Ignatieff was born on May 12, 1947, his father George—a powerful mandarin in the postwar Canadian bureaucracy—moved the family to New York, following his appointment as ambassador to the United Nations.

Michael’s early years in New York were just the beginning of a dizzyingly globetrotting life. In his voluminous autobiographical writings, his introductory preamble inevitably references his “cosmopolitan” credentials. “If anyone has a claim to being a cosmopolitan, it must be me,” he writes in the introduction to Blood and Belonging. A true blue blood, Ignatieff belongs to a privileged, ruling class clan on both his mother’s and his father’s side. His father’s people were the aristocratic elite of the bygone Russian Empire. It’s not hard to envisage Michael’s czarist background, given his patrician bearing, sharp physical features, severe and even pained facial expressions. His bushy eyebrows are a caricaturist’s dream (at one point, during an interview with a comedian on the French-language station Radio-Canada, Ignatieff was put in the unenviable position of addressing the embarrassing fact that a Facebook page devoted to his eyebrows had more fans than his own, official, page; this was then followed by a surreal exchange about the problem of his eyebrows being too social-democratic: “I need liberal eyebrows, at least”3). Grandfather Paul Ignatieff was the last Minister of Education in czarist Russia. Narrowly escaping execution at the hands of the Bolshevik Revolution, he initially took his family to the UK, before settling for exile in Canada. Great-grandfather Nicholas Ignatieff is an infamous figure in Russian history. As a ruthless diplomat, he defended Russia’s imperial claims against her British, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian rivals; Nicholas took part in drawing the national boundaries in the Balkans, the twentieth century’s ultimate powder keg. As Minister of the Interior in the early 1880s, he presided over the worst anti-Jewish pogroms of the nineteenth century.

In The Russian Album (1987), Ignatieff set out to examine the history of his Russian ancestors whom he “chose” because they were more “exotic,” and since he could “always count on my mother’s inheritance” (RA, p. 10). In concluding this exploration of his czarist forebears young Michael’s synthesis dwells primarily on his own journey, seemingly disavowing the Russian roots he has just examined:

I do not believe in roots … I am an expatriate Canadian writer who married an Englishwoman and makes his home overlooking some plane trees in a park in north London. That is my story and I make it up as I go along. Too much time and chance stand between their story and mine for me to believe that I am rooted in the Russian past. Nor do I wish to be. I want to be able to uproot myself when I get stuck, to start all over again when it seems I must. I want to live by my wits rather than on my past. I live ironically, suspicious of what counts as self-knowledge, wary of any belonging I have not chosen. (RA, p. 185)

In both its style and choice of subject matter, his work suggest a restless, intense self-focus. A close reader of Ignatieff once noted that “personal pronouns litter his work.”4 Indeed, a number of his books begin with lengthy meditations about his reasons for writing. In True Patriot Love, he unguardedly concedes: “I can see how vain and distorted our family myth making could be, but for all that, I cannot disavow it. It is part of me” (TPL, p. 23). Ironically, it was to a family retreat in France that Ignatieff escaped to finish writing True Patriot Love, within weeks of taking over as Liberal Party leader in late 2008.

For his Blood and Belonging journeys—shot as a documentary series for the BBC and then put down in book form—Ignatieff admits: “I chose places I had lived in, cared about, and knew enough about to believe that they could illustrate certain central themes” (BB, p. 14). Ignatieff has published three novels, each of which touches on material from his own life. The most critically acclaimed of these, Scar Tissue, is a description of a family with two sons living through their mother’s painful decline through Alzheimer’s disease. Ignatieff is also nearly always a central character in his non-fiction books—at least he won’t have to spend his last years scrambling to put his memoirs together. One might argue that Ignatieff’s declarative, autobiographical style is more honest than the faux detachment of much non-fiction writing. I would argue that his style suits both his purposes and his times. His writings on issues of war and peace, in particular, are light on history and politics. When they are invoked, it is often in passing, and rarely in detail.

In their place, we get psychological explanations and plain moralizing. The latter is buttressed by an attitude of j’y étais, donc je sais;5 Ignatieff’s arguments often cite his personal experience. But paraphrased anecdotes are no substitute for historically informed analysis, and on closer inspection the fact of Ignatieff’s having “been there” is usually beside the point. Anyway, he was no Robert Fisk.6 Even as a war reporter he was really a war commentator, most often arriving after the main fighting to pontificate and lay blame.

A solipsistic style is one thing, but more important are the political consequences of this kind of focus on one’s own reflection. All politicians and leaders in their fields will tend to have a high opinion of their own abilities. Canadian columnist Rick Salutin, however, observed that something more disconcerting is at play with Ignatieff, dubbing him “Narcissieff”:

My own sense is that he’ll make a seriously bad candidate, due to what I’d call his narcissism. This isn’t so much about adoring yourself, as being so self-absorbed that your sense of how others react to you goes missing. A therapist I know says it usually involves “a great deal of self-referencing. A real other doesn’t exist except as an extension of themselves.” This won’t be useful when you’re asking for people’s votes, against other candidates.7

Ignatieff’s repeatedly asserted cosmopolitanism seemed intertwined with his introspective writing, and his apparent need and desire to carve his own path, to “uproot” himself, and to “start all over again.” In a recent work, radical US-based geographer David Harvey draws attention to salient critiques of the faddish re-emergence of so-called cosmopolitanism in certain quarters:

The optimistic cosmopolitanism that became so fashionable following the Cold War, Craig Calhoun points out, not only bore all the marks of its history as “a project of empires, of long-distance trade, and of cities,” it also shaped up as an elite project reflecting “the class consciousness of frequent travelers.” As such, it more and more appeared as “the latest effort to revive liberalism” in an era of neo-liberal capitalism. It is all too easy, concurs Saskia Sassen, “to equate the globalism of the transnational professional and executive class with cosmopolitanism.”8

Indeed, Ignatieff’s cosmopolitan travels and intellectual journey chart the trajectory of liberalism during the years of neo-liberal capitalism’s heyday. He lived in neo-liberalism’s ideological and military centers—Margaret Thatcher’s Britain in the 1980s, George W. Bush’s United States in the first years of the twenty-first century. In the realm of ideas, he traveled from the consensus left liberalism (sprinkled with Marxian analysis) of the social sciences in the academy of the 1970s and early ’80s all the way to leading ideological sorties for the neo-conservative pack as they played out their violent, transformative fantasies with the might of the US empire. His political trajectory was not one of a Left apostate like Christopher Hitchens; it is, rather, a liberal reflection of the political retreats of the Left over the past three decades or more of neo-liberal dominance.

Ignatieff’s around-the-world adventures began with his childhood years in the Big Apple, followed by stints in Belgrade, Paris, Toronto, and Ottawa. He was then dispatched to the male finishing school of choice for Canada’s blue bloods, Ontario’s Upper Canada College. This was followed by an adult itinerary which included Vancouver, Paris, London, Berlin, and journeys to Russia, the Ukraine, Yugoslavia, Rwanda, the Congo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, and more. This doesn’t include vacations, for which the family villa in the South of France has served many times for reunions and retreats, both romantic and literary.

UPPER CANADA COLLEGE: PREP SCHOOL FOR PRIGS

Modeled on Eton College in England, Upper Canada College is Canada’s oldest and most prestigious elite prep school; Prince Phillip, for instance, remains on the Board of Governors. It was founded in 1829, and later moved to Deer Park, now an upper middle-class residential area. A good portion of the Canadian establishment has attended UCC,9 including the media baron and convicted fraudster Conrad Black, who has always worn his expulsion from the College as a badge of honor.

In the early 1960s, when 11-year-old Michael arrived, the College remained a stronghold of Tory conservatism. In a penetrating Globe and Mail piece on Ignatieff, Michael Valpy notes that his years at UCC were an unqualified success:

When he graduated in 1965, he was steward—prefect—of his boarders’ house, captain of the first soccer team, academically at the top of his class, president of the debating club, editor of The College Times yearbook, a member of the library and chapel committees, chair of UCC’s United Appeal, winner of the school’s Nesbitt Cup for debating and a sergeant in the college cadet corps.10

By his own account, the prep school is also where “[he] learned to be an authoritarian prig.” One episode with his younger brother Andrew, which Valpy cites, is especially irksome.

Andrew followed him to UCC in 1962. A self-described “fat little prick,” he was absent his brother’s talents. He was not an athlete, not adept at writing and public speaking, not competitive. While Michael was “God,” and “everybody bowed and scraped when he passed,” Andrew became known as “fatty,” “piggy,” “slob,” “spaz,” “big ass”—and “Iggy,” a nickname he loathed.

Andrew, like Michael, contributed to Old Boys, a collection of reminiscences of UCC—it’s the last public comment he has made about his brother:

Before I started at age 12, our parents sat down with my older brother and me. They said, “Michael, you’re the big brother, and Andrew is going to UCC for the first time. It’s the first time he has ever been away. You have to understand you have to be good to him.”

Michael was very sweet and he told me how wonderful UCC would be. Then we went...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. The Solipsistic Cosmopolitan

- 2. The Negatives of Liberalism

- 3. Balkan Warrior

- 4. Empire’s Handmaiden in Iraq

- 5. Don’t Talk About Palestine

- 6. Staying the Course in Afghanistan

- 7. The Last Invasion

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations for Books by Michael Ignatieff

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Michael Ignatieff by Derrick O'Keefe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.