eBook - ePub

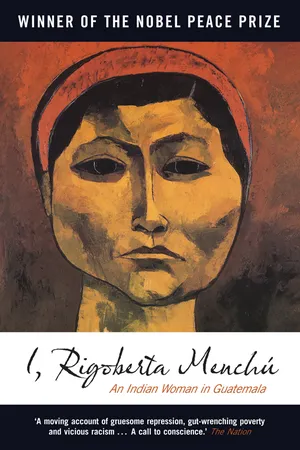

I, Rigoberta Menchú

An Indian Woman in Guatemala

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Now a global bestseller, the remarkable life of Rigoberta Mench?, a Guatemalan peasant woman, reflects on the experiences common to many Indian communities in Latin America. Mench? suffered gross injustice and hardship in her early life: her brother, father and mother were murdered by the Guatemalan military. She learned Spanish and turned to catechistic work as an expression of political revolt as well as religious commitment. Mench? vividly conveys the traditional beliefs of her community and her personal response to feminist and socialist ideas. Above all, these pages are illuminated by the enduring courage and passionate sense of justice of an extraordinary woman.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I, Rigoberta Menchú by Rigoberta Menchú, Elisabeth Burgos-Debray, Ann Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

XI

MARRIAGE CEREMONIES

‘Children, wherever you may be, do not abandon the crafts taught to you by lxpiyacoc, because they are crafts passed down to you from your forefathers. If you forget them, you will be betraying your lineage.’

—Popol Vuh

‘The magic secrets of your forefathers were revealed to them by voices which came by the path of silence and the night.’

—Popol Vuh

I remember that, when we grew up our parents talked to us about having children. That’s the time parents dedicate themselves to the child. In my case, because I was a girl, my parents told me: ‘You’re a young woman and a woman has to be a mother.’ They said I was beginning my life as a woman and I would want many things that I couldn’t have. They tried to tell me that, whatever my ambitions, I’d no way of achieving them. That’s how life is. They explained what life is like among our people for a young person, and then they said I shouldn’t wait too long before getting married. I had to think for myself, learn to be independent, not rely on my parents, and learn many things which would be useful to me in my life. They gave me the freedom to do what I wanted with my life as long as, first and foremost, I obeyed the laws of our ancestors. That’s when they taught me not to abuse my own dignity–both as a woman and a member of our race. They always give the ladinos as an example. Most of them paint their faces and kiss in the street. To our parents this was scandalous. It was a show of disrespect to our ancestors and I was not to do it. If you have a home, your betrothed can come there, if he abides by various customs and the laws of our ancestors. These are all the things our parents tell us. A girl must listen to what her mother tells her; she’ll teach her things she will need one day. They explained all this to me so that I might open the doors of life; so I might learn many things. This is when I began spending more time with my mother and developing as a woman. My mother explained that when I started menstruating, I had begun developing as a woman and could have children. She told me how young women should behave, according to what is laid down in our traditions. For example, if a young man talks to us in the street, we have the right to insult him or ignore him, because our ancestors say it is scandalous for a woman to start courting in the street or do anything behind her parents’ back.

Most children know when their parents are having relations but this doesn’t mean they have a clear idea of what that is. Our parents tell us that we should develop and know all about this aspect, but that’s as far as they go. We don’t even know about the parts of our own bodies, and we don’t know what having babies means. Now I’m critical of that in many ways because I don’t think it is a good thing, and it can be a problem being ignorant of so many things about life.

It’s very rare for a couple not to have children. A lot depends on the medicines the midwife uses. They cure many people with their herbs. I have a cousin who is married and hasn’t any children. The community gives her a lot of affection because they do need a child. Under these circumstances the man can often give in to vices and start drinking. If he hasn’t any children, he only thinks about himself. The woman can become quarrelsome too. If this happens the community slowly loses their sympathy for the couple. They provoke most of the quarrels themselves but sometimes there are women who just don’t like to see a woman without children and some men just don’t like men who’ve no children. This is not the same as rejecting the huecos, as we call homosexuals. Our people don’t differentiate between people who are homosexual and people who aren’t; that only happens when we go out of our community. We don’t have the rejection of homosexuality the ladinos do; they really cannot stand it. What’s good about our way of life is that everything is considered part of nature. So an animal which didn’t turn out right is part of nature, so is a harvest that didn’t give a good yield. We say you shouldn’t ask for more than you can receive. That’s what the ladinos brought with them. It’s a phenomenon that arrived with the foreigners.

Having said that, when our women migrate (leave the village and then come back), they bring with them all the nastiness of the world outside. And they use those plants–medicinal plants found in the fields–to stop themselves having children. In our fields there are remedies which can make you have children at certain times, and at others stop you having children. The outside world–which we know is disgusting–has set a bad example and has started giving us pills and gadgets. There was a big scandal in Guatemala when the Guatemalan Social Security Institute began sterilizing women without telling them, in order to reduce the population. The thing is, to us, using medicine to stop having children is like killing your own children. It’s negating the laws of our ancestors which say we should love everything that exists. So what happens is, our children either die before they are born, or two or so years afterwards, from no fault of our own. It’s the fault of others. The real culprits are those who sow bad seeds on our land. It’s not the Indian’s fault if he gives life to a child and then sees it die of hunger anyway.

The community is very suspicious of a woman like me who is twenty-three but they don’t know where I’ve been or where I’ve lived. She loses the confidence of the community and contact with her neighbours, who are supposed to be looking after her all the time. In this sense, it’s not such a problem when her parents are sure she’s a virgin.

We have four marriage customs to respect. The first is the ‘open door’. It is flexible and there’s no commitment. The second is a commitment to the parents when the girl has accepted the boy. This is a very important custom. The third is the ceremony when the girl and boy make their vows to one another. The fourth is the wedding itself, the despedida. The formalities for getting married are usually carried out in the following way.

The boy first tells his own parents that he likes a certain girl and they tell him what sort of commitment marriage is: ‘You must have children, you have to feed them, and you must never regret what you’ve done for a single day.’ They tell him about the responsibilities a father has. Then, when the young man has made up his mind and so have his parents, they go to the village representative and tell him the boy wants to get married and is going to ask the girl. Then comes the first custom, the ‘open door’, as we say. A door is opened by the village representative, the young man’s parents and then the young man. These requests for marriage usually take place at four in the morning because most Indians leave home before five, and when they come home from work at six in the evening they’re usually busy with other things. It’s done at four in the morning so as not to cause too much inconvenience and they leave when the dogs start barking.

Fathers don’t usually agree to start with, because it’s the custom here to get married very early. Girls often get married at fourteen and are expecting babies by the age of fifteen. The parents object. They say: ‘No, our daughter is too young. She’s too little; she’s a very obedient daughter and we have faith in her.’ So the village representatives go and plead with them, and go back and plead again. The father resists and won’t open the door to ask them in. So they go away. If the young man and his parents are really interested, they have to go back at least three times. After the first time they’ve been, the father begins to talk to his daughter. He explains that a young man is interested in her and tells her all the formalities she will have to go through. The second time the representatives and parents come, they usually bring a little guaro or cigarettes. If the girl’s parents accept a cigarette, that means there is already some small commitment. The door starts to open for the young man. In my sister’s case, when the representatives came the first time, they were refused. My father wouldn’t receive them the second time either because he said; ‘My daughter is too young to be a mother, isn’t she?’ This is because when our people think of marriage, they think of becoming a mother or fulfilling their duty as the father of a family. They also think of gaining the respect of the community, because when a couple gets married in our community, they have to preserve our traditions, and act as an example for their brothers and sisters and for their neighbours’ children. It’s a very important commitment for us.

Well, the young girl starts talking to her parents and she says she would like to know the young man. My father opened the door for my sister when they came for the third time. He was the elected leader of our village, so they had to come with another of the community’s representatives, and my parents finally received them. My father accepted a glass of guaro and some cigarettes. From then on the door was open.

At this stage the parents tell the young man that their daughter is honest and hardworking. This is his parents’ main concern; that the girl is sturdy and works hard and has the energy to stand up to life’s challenges. My parents said my sister had worked like an adult since she was three, that she was an early riser and very diligent. She liked finishing her work quickly; when she worked tilling the land, she’d already finished her task by three in the afternoon. My parents said they never wanted to hear any complaints about her or her behaviour, because she was hardworking and knew how to observe all the traditions of our ancestors.

The young man’s parents also tell them about their son’s bad and good points. They say: ‘Our son is not very good at such and such a thing, but, on the other hand, he knows how to do this and the other.’ It’s a dialogue. Then the representatives leave because the father has to go off to work. But if he’s going to open his door, he must show them hospitality even if he has to stay and chat with them for half a day or a day. The young man is then given permission to call on the daughter another day. But he knows he can’t go just any day because the father, the mother, everybody, are out working in the fields. So he only goes on Sundays. On Sundays, the mother is usually at home doing the washing, or the father is at home while the mother goes to market. One or other of the parents must be at home when the young man arrives…. He doesn’t come empty handed, but brings a little present for the parents–a few rolls of bread, a few cigarettes, or something to drink. He arrives and starts talking to the girl for the first time, since he’d never, never, get to know her in the street. This way the community will respect the girl: they will love her because they know she has begun her marriage with her hands clean. That’s what they say: ‘She’s not one of those girls who hang around the streets. She’s never been seen with a boy in the street.’ In our community, if a girl is seen in the street with a boy, she both loses her dignity and breaks the customs of our forefathers.

Of course, if the girl doesn’t like the boy, she can say so. If she doesn’t like him, she carries on working even if her parents open the door. She finds things to do and has no time for him. She doesn’t talk to him. That’s a signal she doesn’t like him. Everyone waits for fifteen days to see if she’s going to talk to him. If she doesn’t, they tell him it isn’t the family, but the girl who isn’t interested. This often happens. But if she accepts him, there will always be someone in the house when he calls; they’ll never be alone. This is to preserve the woman’s purity, which is something sacred, something special, something which will engender many lives. The woman has to be respected, so the parents are always around. In my sister’s case, she decided about seven months after she and the young man first talked together. He came to see her all the time without any commitment either on her part or his. Just the ‘open door’. Then my sister decided. The day the girl agrees, the young man gets down on his knees in front of her parents and says that on such and such a day he will come with his parents.

Certain traditions are respected. For example, when the people come to ask for the door to be opened for the first time, they don’t stand up but go down on their knees in front of the door. My father didn’t open the door the first time, and the second time they kneeled at the door, he still didn’t open. On the third occasion the door was opened and they offered my father a drink; the young man remaining on his knees. It’s a form of great respect. As my parents say, a person who knows how to kneel is a humble person, so from the way the young man kneels the parents can tell whether he knows how to respect our ancestors.

It is decided straight away who will take part in the ceremonies. There will be the couples’ eldest uncle and his wife, their brothers and sisters, or rather their elder brothers and sisters, the village representatives, and the grandparents of both the young man and the girl. So the second stage of the marriage ritual begins. There is a fiesta at home with all the family; grandmother, grandfather, uncles and aunts, elder brothers and sisters are all there. It’s like the fiesta for the birth of a baby, when a lamb is killed. Now the parents kill the biggest lamb in their flock and bring it to the house. The uncles arrive with dough for the tortillas. The whole family makes a contribution. The grandmother must bring her granddaughter a present. Grandmothers keep the silver jewellery passed down from our forefathers, and now the grandmother gives the young girl a necklace or something as a keepsake and to encourage her. In return, she makes a promise to be just like her grandmother and to keep our ancestors’ traditions in the same ways she did.

Then the house is prepared and the food is made for the fiesta. For their part, the young man’s parents make preparations too. They bring something for the girl as an engagement present: usually something given to the young man when he was born. They also bring a live lamb and another already prepared to eat. The dough for the feast is made into larger tamales than usual and they usually make about seventy-five of them. These tamales last a long time: they will last the girl’s parents about a week because they’re big and don’t go bad, or at least the outside does but not the inside. These big tamales give a party feeling to the meal.

These seventy-five big tamales brought by the boy’s parents weigh about two or three quintals altogether, because each tamal is about eight pounds in weight. For us Indians, each tamal represents a sacred day. We count the days that we ask the earth’s permission to sow our crops, the eight sacred days a baby is with his mother, the sacred days of our fiestas and the ceremonies throughout a child’s life from birth to marriage: when he was born, when he became a member of the community, when he was baptized, his tenth birthday, and so on. Each child has his own sacred day. Even if he’s working, it’s still his sacred day. These days are always sacred for him. In addition, we count other sacred days, like the day we ask the trees’ permission to cut them down because we need to clear the land for cultivation. For us, all things have their sacred days even if, because of our circumstances, we don’t have the time to observe their rituals very faithfully. Then there are all the saints’ days, from the Catholic Action. But ours are not the saints of the pictures. We celebrate special days talking about our ancestors; for us in the month of October, a whole part of the month is sacred because this is the time they used to worship and keep their silence. We preserve this tradition too. All the sacred days of the year add up to seventy-two or seventy-five days, and each tamal represents one day.

So the young man’s family brings seventy-five tamales, a live lamb and one ready prepared for eating. They also usually bring a large earthenware jar of soup made from the lamb when it’s killed. Altogether this is a pretty big load. They take the cooked meat to a place set aside for it and one person is put in charge of it. The tamales need at least four boys in charge of them, so a whole lot of them line up for the job. But not just any boys are chosen, they have to be ones who are respected by the community. They will serve the drinks and give out the cigarettes at the fiesta after the ceremony. They are usually the young man’s brothers or cousins, except if any of them are naughty, or not very sociable, he won’t be chosen to help at the fiesta.

When the guests arrive, they come in in a line. First comes the representative of the young man’s village with his wife, and greet the girl’s parents. Then the father kneels in a corner that has been specially prepared. If they still live in the same house where the girl was born, this will be the place where they put the candles when she was received into the natural world. If it is the same place, the parents will still have the remains of those candles and will use them now. This is still not the marriage rites, however, as there are still certain customs to perform. They come and kneel down in the corner where the candles are, without saying a word or acknowledging each other. The doors are opened and the rest of the people come in and kneel down. Then the girl’s mother and father come in. The mother’s role is very important here, because she is someone special, the person who has given life to her daughter and in whose image her daughter must live. She is the one who goes to each person and asks them to get up off their knees. She goes first to the young man’s mother and asks her to stand and then goes to each person who is kneeling, individually. The father shows them where to sit. They can’t sit just anywhere all mixed up, because the order in which the cups of guaro are drunk is very important and the elderly people have to be served first and then the rest. We drink a lot of guaro, more than anything else. Some guaro is clandestine: forbidden by the Guatemalan government. We Indians make it and use it for all our ceremonies. This guaro is very strong, and it’s very cheap. They don’t like us making it because it lowers the price in the cantinas. It’s made in the mountains, in tree trunks and in earthenware jars. It’s made from fermented maize and the bran we use to feed our horses, or from wheat–the chaff of the wheat. It can also be made from rice or sugar cane. It’s always very strong. The parents provide enough guaro for everybody.

The mother asks the boy’s mother to stand first, then his grandmother and then all the other people. The girl’s father is busy showing everyone where to sit. There is a special seat for each one. The ceremony begins. The girl goes out. The young man remains on his knees. She comes in again and kneels some way away from him. They remain kneeling for about fifteen or twenty minutes. The ceremony begins with the grandparents’ account of their suffering, the sadness and the joy in their life. They give a sort of general account of their life–that at this moment or that moment they were ill but they never lost hope, that their ancestors had also suffered in the same way, and many, many other things. Then the couple who are getting married say a prayer: ‘Mother Earth, may you feed us. We are made of maize, of yellow maize and white maize.’ And then the couple says other prayers to our one God, the heart of the sky who embraces the whole natural world. They talk to the heart of the sky, saying: ‘Father and Mother, Heart of the Sky, may you give us light, may you give us heat, may you give us hope and punish our enemies–all those who wish to destroy our ancestors. We, poor and humble as we are, will never abandon you.’

They make a new pledge to honour the Indian race. They affirm our importance. They say it is the duty of each one of us to reproduce the earth and the traditions of our ancestors, who were humble. They refer back to the time of Columbus and say: ‘Our forefathers were dishonoured by the white man–sinners and murderers’ and: ‘It is not the fault of our ancestors. They died from hunger because they weren’t paid. We want to destroy the wicked lessons we were taught by them. If they h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Translator’s note

- Introduction

- I The family

- II Birth ceremonies

- III The nahual

- IV First visit to the finca. Life in the finca

- V First visit to Guatemala City

- VI An eight-year-old agricultural worker

- VII Death of her little brother in the finca. Difficulty of communicating with other Indians

- VIII Life in the Altiplano. Rigoberta’s tenth birthday

- IX Ceremonies for sowing time and harvest. Relationships with the earth

- X The natural world. The earth, mother of man

- XI Marriage ceremonies

- XII Life in the community

- XIII Death of her friend by poisoning

- XIV A maid in the capital

- XV Conflict with the landowners and the creation of the CUC

- XVI Period of reflection on the road to follow

- XVII Self-defence in the village

- XVIII The Bible and self-defence: the examples of Judith, Moses and David

- XIX Attack on the village by the army

- XX The death of Doña Petrona Chona

- XXI Farewell to the community: Rigoberta decides to learn Spanish

- XXII The CUC comes out into the open

- XXIII Political activity in other communities. Contacts with ladinos

- XXIV The torture and death of her little brother, burnt alive in front of members of his family and the community

- XXV Rigoberta’s father dies in the occupation of the Spanish embassy. Peasants march to the capital

- XXVI Rigoberta talks about her father

- XXVII Kidnapping and death of Rigoberta’s mother

- XXVIII Death

- XXIX Fiestas and Indian queens

- XXX Lessons taught her by her mother: Indian women and ladino women

- XXXI Women and political commitment. Rigoberta renounces marriage and motherhood

- XXXII Strike of agricultural workers and the First of May in the capital

- XXXIII In hiding in the capital. Hunted by the army

- XXXIV Exile

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Further Reading