- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Class

About this book

Few ideas are more contested today than "class." Some have declared its death, while others insist on its centrality to contemporary capitalism. It is said its relevance is limited to explaining individuals' economic conditions and opportunities, while at the same time argued that it is a structural feature of macro-power relations. In Understanding Class, leading left sociologist Erik Olin Wright interrogates the divergent meanings of this fundamental concept in order to develop a more integrated framework of class analysis. Beginning with the treatment of class in Marx and Weber, proceeding through the writings of Charles Tilly, Thomas Piketty, Guy Standing, and others, and finally examining how class struggle and class compromise play out in contemporary society, Understanding Class provides a compelling view of how to think about the complexity of class in the world today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

FROM GRAND PARADIGM BATTLES TO PRAGMATIST REALISM: TOWARDS AN INTEGRATED CLASS ANALYSIS

When I began writing about class in the mid-1970s, I saw Marxism as a comprehensive paradigm confronting positivist social science.1 I argued that Marxism had distinctive epistemological premises and distinctive methodological approaches that were fundamentally opposed to the prevailing practices of mainstream social science. While I argued that this battle should be engaged on empirical as well as theoretical terrain, I viewed Marxism and mainstream sociology as foundationally distinct and incommensurable warring paradigms. Looking back in the mid-1980s at this earlier work, I wrote: “I originally had visions of glorious paradigm battles, with lances drawn and the valiant Marxist knight unseating the bourgeois rival in a dramatic quantitative joust. What is more, the fantasy saw the vanquished admitting defeat and changing horses as a result.”2

Nearly four decades have passed since this early work on class. In the intervening period I have rethought the underlying logic of my approach to class analysis a number of times.3 While I continue to work within the Marxist tradition, I no longer feel that the most useful way of thinking about Marxism is as a comprehensive paradigm that is incommensurate with “bourgeois” sociology.4 Rather, I see different theoretical traditions as identifying different kinds of causal processes or mechanisms, which they claim have explanatory power for particular agendas. These different traditions have scientific value to the extent that these claims are justified. The different mechanisms elaborated by different theoretical traditions intersect and interact in the world, generating the things we observe. The Marxist tradition is a valuable and interesting body of ideas because it successfully identifies real mechanisms that matter for a wide range of important problems, but it does not constitute a fullblown “paradigm” capable of comprehensively explaining all things social or subsuming all social mechanisms under a unified framework. It also does not have a monopoly on the capacity to identify real mechanisms, and thus in practice sociological research by Marxists should combine distinctive Marxist-identified mechanisms with whatever other causal processes seem pertinent to the tasks at hand. What might be called “pragmatist realism” has replaced the Grand Battle of Paradigms.

Pragmatist realism does not imply simply dissolving Marxism into some amorphous “sociology” or social science. Marxism remains distinctive in organizing its agenda around a set of fundamental questions and problems which other theoretical traditions either ignore or marginalize. It is distinctive in its normative commitments to class emancipation. And it is distinctive in identifying a specific set of interconnected causal processes relevant to those questions and emancipatory ideals. These elements constitute the anchors for a distinctive intellectual tradition of emancipatory social science, but they are not the basis for an exclusionary paradigm.5

In this chapter I explore some of the implications of this pragmatist realism for class analysis. In my theoretical work in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I argued for the general superiority of the Marxist concept of class over its main sociological rivals—especially Weberian concepts of class and class within mainstream stratification research. It now seems to me more appropriate to see these different ways of talking about class as each identifying different clusters of causal processes at work in shaping the micro and macro aspects of economically rooted inequality in capitalist societies. For some questions and problems, one or another of these clusters of mechanisms may be more important, but all are relevant to a full sociological understanding of economic inequality and its consequences. Each of these approaches to class analysis is incomplete if it ignores the others. I continue to feel that Marxist class analysis is superior to the other traditions for a range of questions that I feel are of central importance, especially questions about the nature of capitalism, its harms and contradictions, and the possibilities of its transformation. But even for these core Marxist questions, the other traditions of class analysis have something to offer.

For simplicity in this discussion, I focus on three clusters of class-relevant causal processes, each associated with different strands of sociological theory and approaches to class analysis. The first identifies class with the attributes and material conditions of the lives of individuals. The second focuses on the ways in which social positions give some people control over economic resources of various sorts while excluding others from access to those resources. And the third identifies class, above all, with the ways in which economic positions give some people control over the lives and activities of others. I call these three approaches the individual-attributes approach to class, the opportunity-hoarding approach, and the domination and exploitation approach. The first is associated with the stratification tradition, the second with the Weberian tradition, and the third with the Marxist tradition.6

CLASS AS INDIVIDUAL ATTRIBUTES

Among both sociologists and the lay public, the principal way that most people understand the concept of class is in terms of individual attributes and life conditions. People have all sorts of attributes, including sex, age, race, religion, intelligence, education, geographical location, and so on. Some of these attributes they have from birth, some they acquire but once acquired are very stable, and some are quite dependent on a person’s specific social situation at any point in time and may accordingly change. These attributes are consequential for various things we might want to explain, from health to voting behavior to childrearing practices. People can also be characterized by the material conditions in which they live: squalid apartments, pleasant houses in the suburbs, or mansions in gated communities; dire poverty, adequate income, or extravagant wealth; insecure access to health services or excellent health insurance and access to high-quality services. “Class,” then, is a way of talking about the connection between individual attributes and these material life conditions: class identifies those economically important attributes of people that shape their opportunities and choices in a market economy and thus their material conditions of life. Class should neither be identified simply with the individual attributes nor with the material conditions of life of people, but with the interconnections between these two.

The key individual attribute that is part of class in economically developed societies within this approach is education, but some sociologists also include somewhat more elusive attributes such as cultural resources, social connections, and even individual motivations.7 All of these deeply shape the opportunities people face and thus the income they can acquire in the market, the kind of housing they can expect to have, the quality of the health care they are likely to get, and much more.

When these different attributes of individuals and material conditions of life broadly cluster together, these clusters are called “classes.” The “middle class,” within this approach to the study of class, identifies people who are more or less in the broad middle of the economy and society: they have enough education and money to participate fully in some vaguely defined “mainstream” way of life. “Upper class” identifies people whose wealth, high income, social connections, and valuable talents enable them to live their lives apart from “ordinary” people. The “lower class” identifies people who lack the necessary educational and cultural resources to live securely above the poverty line. And finally, the “underclass” identifies people who live in extreme poverty, marginalized from the mainstream of American society by a lack of basic education and skills needed for stable employment.

While most research within the individual-attributes approach discusses class using loose gradational terms like upper, middle and lower class, there are some currents that attempt to specify an array of more qualitatively distinguished categories. A good example is the work of Mike Savage and his colleagues in their analysis of what has come to be known as the “Great British Class Survey.”8 Along the lines of the work of Pierre Bourdieu, they define the abstract concept of class in terms of three dimensions of economically relevant resources which individuals possess: economic capital, cultural capital, and social capital. They then ask the empirical question: how many classes can be empirically distinguished based on the ways in which indicators of these three dimensions of individual attributes cluster together? Their answer, using fairly sophisticated inductive statistical strategies, is that there are seven classes in Britain today: elite; established middle class; technical middle class; new affluent workers; traditional working class; emergent service workers; and precariat.

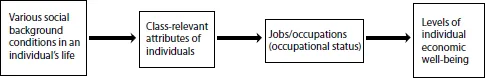

In the individual-attributes approach to class, the central concern of sociologists has been to understand how people acquire the attributes that place them in one class or another. For most people in the countries where sociologists live, economic status and rewards are mainly acquired through employment in paid jobs, so the central thrust of much research in this tradition is on the process by which people acquire the cultural, motivational, and educational resources that affect their occupations in the labor market. Because the conditions of life in childhood are clearly of considerable importance in these processes, this tradition of class analysis devotes a great deal of attention to what is sometimes called “class back-ground”—the class character of the family settings in which these key attributes are acquired. The causal logic of these kinds of class processes is illustrated in a stripped-down form in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. The Individual-Attributes Approach to Class and Inequality

Skills, education, and motivations are, of course, very important determinants of an individual’s economic prospects. What is missing in this approach to class, however, is any serious consideration of the inequalities in the positions themselves that people occupy. Education shapes the kinds of jobs people get, but how should we conceptualize the nature of the jobs that people fill by virtue of their education? Why are some jobs “better” than others? Why do some jobs confer on their incumbents a great deal of power while others do not? Rather than focusing exclusively on the process by which individuals are sorted into positions, the other two approaches to class analysis begin by analyzing the nature of the positions themselves into which people are sorted.

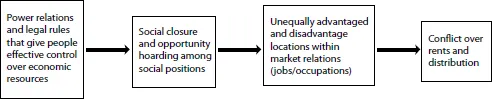

CLASS AS OPPORTUNITY HOARDING

The problem of “opportunity hoarding” is closely associated with the work of Max Weber.9 The idea is that if a job is to confer on its occupants high income and special advantages it is important that the incumbents of those jobs have various means of excluding other people from access to the jobs. This is also sometimes referred to as a process of social closure, the process whereby access to a position becomes reserved for some people and closed off to others. One way of achieving social closure is by creating requirements for filling the job that are very costly for people to meet. Educational credentials often have this character: high levels of education generate high income in part because of significant restrictions on the supply of highly educated people. Admissions procedures, tuition costs, risk aversion to large loans by low-income people, and a range of other factors all block access to higher education for many people, and these barriers benefit those in jobs that require higher education. If a massive effort was made to improve the educational level of those with less education, this program would itself lower the value of education for those who already have it, since its value depends to a significant extent on its scarcity. The opportunity-hoarding mechanism is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2. The Opportunity-Hoarding Approach to Class and Inequality

Some might object to this description of educational credentials by arguing that education also affects earnings by enhancing a person’s productivity. Economists argue that education creates “human capital,” which makes people more productive, and this higher productivity makes employers willing to pay them higher wages. While some of the higher earnings that accompany higher education reflect productivity differences, this is only part of the story. Equally important are the ways in which the process of acquiring education excludes people through various mechanisms and thus restricts the supply of people available to take these jobs. A simple thought experiment shows how this works: imagine that the United States had open borders and let anyone with a medical degree or engineering degree or computer science degree anywhere in the world come to the United States and practice their profession. The massive increase in the supply of people with these credentials would undermine the earning capacity of holders of the credentials even though their actual knowledge and skills, and thus their productivity, would not be diminished. Citizenship rights are a special, and potent, form of “license” to sell one’s labor in a labor market.

Credentialing and licensing are particularly important mechanisms for opportunity hoarding, but many other institutional devices have been used in various times and places to restrict access to given types of jobs: color bars excluded racial minorities from many jobs in the United States, especially (but not only) in the South until the 1960s; marriage bars and gender exclusions restricted access to certain jobs for women until well into the twentieth century in most developed capitalist countries; religion, cultural style, manners, accent—all of these have constituted mechanisms of exclusion.

Perhaps the most important exclusionary mechanism that protects the privileges and advantages of people in certain jobs in a capitalist society is private property rights in the means of production. Private property rights are the pivotal form of exclusion that determines access to the “job” of capitalist employer. If workers were to attempt to take over a factory and run it themselves they would be violating this process of closure by challenging their exclusion from control over t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. From Grand Paradigm Battles to Pragmatist Realism: Towards an Integrated Class Analysis

- Part 1: Frameworks of Class Analysis

- Part 2: Class in the Twenty-First Century

- Part 3: Class Struggle and Class Compromise

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Class by Erik Olin Wright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Political Economy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.