- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

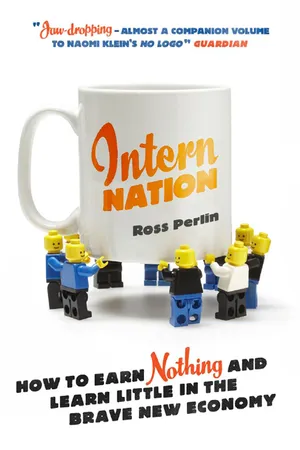

About this book

Millions of young people-and increasingly some not-so-young people-now work as interns. They famously shuttle coffee in a thousand magazine offices, legislative backrooms, and Hollywood studios, but they also deliver aid in Afghanistan, map the human genome, and pick up garbage. Intern Nation is the first expos? of the exploitative world of internships. In this witty, astonishing, and serious investigative work, Ross Perlin profiles fellow interns, talks to academics and professionals about what unleashed this phenomenon, and explains why the intern boom is perverting workplace practices around the world.

The hardcover publication of this book precipitated a torrent of media coverage in the US and UK, and Perlin has added an entirely new afterword describing the growing focus on this woefully underreported story. Insightful and humorous, Intern Nation will transform the way we think about the culture of work.

The hardcover publication of this book precipitated a torrent of media coverage in the US and UK, and Perlin has added an entirely new afterword describing the growing focus on this woefully underreported story. Insightful and humorous, Intern Nation will transform the way we think about the culture of work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Intern Nation by Ross Perlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Labour Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Happiest Interns in the World

Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest [of America] is real …

—Jean Baudrillard1

The curtain rises on Disney World: interns are everywhere. The bellboy carrying luggage up to your room, the monorail “pilot” steering a Mark VI train at forty miles per hour, the smiling young woman scanning tickets at the gate. Others corral visitors into the endless line for Space Mountain, dust sugar over funnel cake, sell mouse ears, sweep up candy wrappers in the wake of bewitched four-year-olds. Even Mickey, Donald, Pluto and the gang—they may well be interns, boiling in their fur costumes, close to fainting in the Florida heat.

Visiting the Magic Kingdom recently, I tried to count them, scanning for the names of colleges on the blue and white name tags that all “cast members” wear. I met interns from Kent State in Ohio, from Lock Haven University in Pennsylvania, Lehman College in the Bronx, Miami-Dade College, Kean College in New Jersey, and the University of Nebraska. They came from public schools and private ones, little-known community colleges and world-famous research universities, from both coasts and everywhere in between. International interns, hailing from at least nineteen different countries, were also out in force. A sophomore from Shanghai, still bright-eyed a week into her internship, greeted customers at the Emporium on Main Street, U.S.A. She was one of hundreds of Chinese interns, she told me, and she was looking forward to “earning her ears.”

These were just a few foot soldiers out of Disney’s intern legions. Beyond the Magic Kingdom stretch three more theme parks, two water parks, twenty-four on-site themed hotels, an entire “downtown,” countless restaurants and stores, a full-blown transportation system, and a host of other miscellaneous “entertainment and recreational venues.” The world of Disney sprawls untrammeled over forty square miles, almost all of it thick with interns. Further hordes waited “off-stage” and out of sight—in warehouses, in kitchens, or underground in “the utilidors”: a nineacre tunnel system of warehouses, hallways, and offices, home to the computer system that programs parades, cues fireworks, and runs a vast surveillance network. Then there are the four gated residential complexes, some miles off, where Disney requires these low-paid thousands to live.

Disney runs one of the world’s largest internship programs. Each year, between 7,000 and 8,000 college students and recent graduates work fulltime, minimum-wage, menial internships at Disney World. Typical stints last four to five months, but the “advantage programs” may go on for up to seven months. These programs all overlap with the academic year. Rather than offer traditional summer internships, Disney’s schedule is determined by the company’s manpower needs, requiring students to temporarily suspend their schooling or continue it on Disney property and on Disney terms. The interns work entirely at the company’s will, subject to a raft of draconian policies, without sick days or time off, without grievance procedures, without guarantees of workers’ compensation or protection against harassment or unfair treatment. Twelve-hour shifts are typical, many of them beginning at 6 a.m. or stretching past midnight. Interns sign up without knowing what jobs they’ll do or the salaries they’ll be paid (though it typically hovers right near minimum wage).

“Do any of these guests know that if not for these students their vacations would not exist?” asks former intern Wesley Jones in his book Mousecatraz.2 Although sometimes more inclined to rumors than to rigorous research, Mousecatraz is the one suggestive, in-depth look at the Disney program, written by someone who clearly knows it well and has talked to hundreds of other Disney alumni.

Disney labor is meant to have an almost invisible quality. Except for the name tags, nothing obvious distinguishes interns for the casual visitor—and now, in certain parts of the park, at certain times of day, they are simply the norm, comprising over 50 percent of staff. The work they perform is identical to what permanent employees do, and there’s no added supervision, training, or mentoring on the job. The educational component is meant to come from a three- or four-hour class each week, offering some of the easiest college credits in the land. Students are also encouraged to obtain credit through networking, distance-learning, and “individualized learning opportunities.” In any case, many interns do nothing educational at all, in the traditional sense of the word, given that Disney doesn’t require it and that twelve-hour shifts are exhausting enough already.

Like other employers across the country, Disney has figured out how to rebrand ordinary jobs in the internship mold, framing them as part of a structured program—comprehensible to educators and parents, and tapping into student reserves of careerism and altruism. “We’re not there to flip burgers or to give people food,” a fast food intern told the Associated Press. “We’re there to create magic.”3 Should the magic fail, the program at least seems to promise professional development and the prestige of the Disney name, said to stand out on a résumé regardless of the actual work performed. Yet training and education are clearly afterthoughts: the kids are brought in to work. Having traveled thousands of miles and barely breaking even financially, they find themselves cleaning hotel rooms, performing custodial work, and parking cars. The housing provided is hardly given out of generosity, but rather a calculated move to scale the program to massive proportions, where the real savings of not employing full-timers kick in. Communal housing may be part of what makes the experience fun and memorable, just like college, but day-to-day life at its worst looks suspiciously like a term of indenture: living on company property, eating company food, and working when the company says so.

In its scale and daring, the Disney Program is unusual, if not unique—a “total institution” in the spirit of Erving Goffman.4 Although technically legal, the program has grown up over thirty years with support from all sides and almost zero scrutiny to become an eerie model, a microcosm of an internship explosion gone haywire. An infinitesimally small number of College Program “graduates” are ultimately offered full-time positions at Disney. A harvest of minimum-wage labor masquerades as an academic exercise, with the nodding approval of collegiate functionaries. A temporary, inexperienced workforce gradually replaces well-trained, decently compensated full-timers, flouting unions and hurting the local economy. The word “internship” has many meanings, but at Disney World it signifies cheap, flexible labor for one of the world’s largest and best-known companies—magical, educational burger-flipping in the Happiest Place on Earth.

Like many a corporate titan, Disney likes to give the impression it’s in the education business. Disney University, born in 1955 as the company’s training division, beat McDonald’s Hamburger University, Motorola University, and others to the punch, prefiguring what Andrew Ross has called “the quasi-convergence of the academy and the knowledge corporation.” Since 1996, the Disney Institute has charged “millions of attendees representing virtually every sector of business from every corner of the globe” for the privilege of learning about Disney’s “brand of business excellence.”5 The Disney Career Start Program attracts high school drop-outs and graduates, promising a custom-designed “learning curriculum.” The Disney Dreamers Academy targets 100 high school students each year. Interns are not the only ones on the receiving end of a dubious Disney degree. The company has every demographic, every part of the life cycle, covered.

The very name Disney World honors the universal intentions of a single individual. But there is also a much more prosaic title for these 25,000 acres of former swampland: the Reedy Creek Improvement District (RCID). An administrative fiction signed into law by Florida Governor Claude Kirk, Jr., in May 1967, RCID effectively granted the Walt Disney Corporation free rein over a sizable chunk of central Florida.6 Yielding an unprecedented fiefdom to the imagineers of Burbank, the move enthusiastically welcomed a fait accompli—for the previous three years, Disney had been covertly amassing tens of thousands of acres in Orange and Osceola counties for a nebulous and grandiose “Florida Project.” Keeping its intentions secret from local communities, partly in order to prevent a land rush, Disney deployed willing proxies, shell companies, and other false fronts: the Compass East Corporation; Tomahawk Properties, Inc.; Ayefour Corporation; and the Latin-American Development and Management Corporation, among others.

RCID continues to be the Walt Disney Corporation in all but name, allowing the company a quasi-governmental authority, including the extraordinary power to pay certain taxes to itself and to make land use decisions virtually without obstruction. The unique arrangement has been one of the principal factors in the remarkable expansion of Disney World attractions over the past two decades—another has been a compliant, scalable workforce of young people, employed at the company’s whim and under educational pretenses.

With some 63,000 people now working on the property, Disney World is the largest single-site employer in the U.S. With the 1978 announcement of the building of EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow), Duncan Dickson and his fellow managers in Disney’s Casting Department (read: Human Resources) conducted a manpower forecast to gauge their readiness for the coming build-up. Dickson says the prospects of finding enough workers in the Greater Orlando region looked bleak. At the time, the big question was “Where were we going to get these five to six thousand people?”

Dickson and his colleague John Brownley thought of Harry Purchase, head of the Hotel Management Department at Paul Smith’s College in upstate New York. Through connections on the Disney staff, Purchase had been bringing his students to the Magic Kingdom every summer since 1972 to work in the Food and Beverage division and take classes with him off-site. Then in 1978 came a year-round arrangement with the much larger Johnson and Wales College in Rhode Island, which wanted to increase its enrollment of culinary students without building more kitchen space on campus. As Dickson remembers, the school proposed that “they would send an instructor down, they would have classes offsite … and the students would work.” Disney readily agreed.

Could these minor applied learning initiatives be magnified into something significant, wondered Dickson and Brownley, big enough to make a serious dent in Disney’s hiring needs? In early 1980, they hosted a three-day meeting in Orlando with a few dozen educators—“department heads of various programs and directors of cooperative education from different universities”—with the goal of setting out “a blueprint for the College Program.” The educators were strongly supportive of the concept, stressing only that Disney should handle housing and provide some sort of classroom experience. The senior Disney executive in charge of all the theme parks gave his enthusiastic approval—after all, Disney parks had always employed some number of college students and young people, like many service providers. The idea of the College Program was simply to institutionalize and legitimize this on a massive scale, tapping colleges as key sources of recruitment and closely controlling the entire process. “To build it to any size, we had to have the academic piece,” says Dickson. Besides scale, “the other impetus was to provide a flexible labor force that can adjust to [seasonal] operating fluctuations.”

The Magic Kingdom College Program launched in the summer of 1980, restricted at first to some 200 students from three universities in the southeastern U.S. The immediate plan was to ramp the intake up to 400 interns in spring and summer (then the busiest times in the park) and drop to 200 in the fall. Until 1988, interns lived in the Snow White Village Campground, a mobile home park set amidst the strip malls and discount motels in the nearby town of Kissimmee. The units there usually accommodated eight people in four bedrooms, sharing two bathrooms and a kitchen. Then as now, housing was required for interns and the cost was deducted directly from their paychecks, in part for sheerly economic reasons. According to Dickson: “The company has to go out and secure the housing, so then to have students say, ‘I don’t want to live there,’ [leaves the company with] the financial obligation, so that creates an issue.”

Renamed twice to capture its widening scope (first to other parks inside Disney World and recently to California), the College Program has employed more than 50,000 interns over the thirty years of its existence. Its expansion has been exponential and opportunistic. The program has spawned imitations at the Disney theme parks in Hong Kong and Paris. From the late 1980s through the 1990s, more than 10,000 new hotel rooms were built at Disney World. Interns were promptly rushed in to fill a large number of the new positions, although hotel work had not originally been part of the program. The earlier focus on students majoring in hospitality, theme park management, or culinary arts disappeared as Disney ceased to require or seek out students studying particular majors: now you’re more likely to find history majors dunking fries in hot oil and psychology majors working as lifeguard-interns. The loosening of immigration regulations in the late 1990s prompted the massive recruitment of ICP’s (International College Program interns), more than 1,000 of whom now come to work at Disney World each year, under dubious interpretations of the J-1 “cultural exchange” and H2B “seasonal work” visas.

If Disney’s motives are transparent and readily grasped, more surprising is the passionate support of Disney’s dozens of cheerleaders at colleges and universities. Dickson himself, who ran the program until 1995, is now an Assistant Professor of Hospitality Management at Rosen College, down the road from Disney: a symbol of the easy traffic between academic departments and industry in “experiential” fields. In another example, Kent Phillips, Educator Relations and New Market Development Specialist for the internship program, recently received a major award for his good offices from the Cooperative Education and Internship Association.

In a promotional video aimed at students, over a dozen internship coordinators, career counselors, and professors of experiential education intone one after the other:

“Disney is not just a place to work—it’s an experience, and it’s an experience you can’t get anywhere else.”

“We tell students that the Disney College Program is for students of all majors, from engineers to business to students in the liberal arts.”

“The best thing … is what it does for the students’ self-esteem.”

“They’ve learned people skills, they’ve learned accountability, they’ve learned how to be creative decision makers.”

“By far the best intern program I’ve seen in the nation.”

Do the colleges understand that Disney sees their students as “a market” to “develop”? Why are twenty-two educators—including college provosts and the Executive Director of the National Association of Colleges and Employers (a major voice on internships)—willing to sit on an advisory board for the program, while many others serve as “faculty representatives” for Disney at their respective colleges?7 Uncompensated “campus representatives”—former interns who want to keep their free passes to Disney parks—spread the message on hundreds of campuses across the country, assisting a staff of full-time Disney College Program recruiters during countless presentations each year. Educators and campus career development professionals are patently thrilled to have been consulted by Disney and to feel that they can offer their students a way in to a major name-brand company.

More troubling than this is the imprimatur of academic credit that these colleges lend to laboring for Disney: a summer job with a thin veneer of education, virtually unleavened by substantive academic content. After all, the thousands of students who do receive academic credit are paying their schools per credit for the privilege—a considerable financial windfall for schools, considering the minimal cost of providing these credits. If an institution refuses credit, Disney helps its interns look elsewhere, to more accommodating colleges and universities that are happy for the revenue stream, no matter where the students are from or what they do. Among those which have made arrangements with Disney are Purdue, the University of North Carolina, Tulane, and Central Michigan University (which charges up to $2,630 in any given semester). In order for its legions of international interns to secure their J-1 visas, Disney has also concocted relationships between willing American schools and foreign counterparts, such that—to take a single example—Montclair State University can charge thousands of dollars of tuition for a student from Beijing to work for Disney at minimum wage.

It would be unfair to assume that the educators involved are prompted solely by mercenary motives. Bud Miles, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, which has sent hundreds of students to the program, told a reporter that “when the students come back here, I have local employers ask me if they can have some of the students who were in the Disney program … because Disney has such a reputation in the area of customer service.” Educators acknowledge that Disney’s name recognition alone can help break the ice during a job interview. But many also subscribe to an educational philosophy wherein Disney World, or perhaps any workplace, is “a learning laboratory,” as Disneyspeak would have it, and for these experts, the distinction between work and education has become almost nonexistent. According to Dickson, the approving educators have been “absolutely” aware from the beginning that the majority of interns work in fast food and sit-down restaurants, park cars, clean up after guests, and perform other routine maintenance tasks—indistinguishable by all accounts from the work performed by regular employees. Jerry Montgomery, another member of Disney’s HR team involved in managing the program early on, defends it as helping to manage students’ career expectations. Not everyone in life gets to be “the CFO’s assistant,” says Montgomery, and young people trying to get ahead often need a reality check, someone to “slap them upside the head”—something Disney presumably accomplishes by giving its interns mundane, real-world roles. Dickson points to “guest contact,” along with showing up on time and being neatly attired, as key educational components. Yet many intern roles are now entirely “backstage,” and even so, should service industry experience count as formal education just because you deal with customers?

Having secured its new cheap labor source, Disney could afford to let the program’s academic facade crumble a bit—apparently less than half of all interns now seek or receive credit, far fewer than was initially the case. One Disney recruiter reassured his audience of intern hopefuls that it is “a networking program”—“a lot of students don’t take classes: d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: The Rules of the Game

- 1. The Happiest Interns in the World

- 2. The Explosion

- 3. Learning From Apprenticeships

- 4. A Lawsuit Waiting to Happen

- 5. Cheerleaders on Campus

- 6. No Fee for Service

- 7. The Economics of Internships

- 8. Futures Market

- 9. What About Everybody Else?

- 10. The Rise and Rebellion of the Global Intern

- 11. Nothing to Lose but Your Cubicles

- Afterword to the Paperback Edition

- Notes

- Appendix A: Intern Bill of Rights

- Appendix B: Internships and the Law

- Acknowledgments

- Index