eBook - ePub

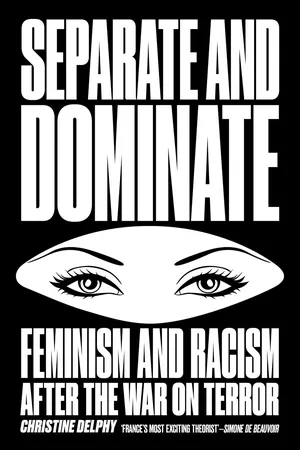

Separate and Dominate

Feminism and Racism after the War on Terror

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Feminist Christine Delphy co-founded the journal Nouvelles questions f?ministes with Simone de Beauvoir in the 1970s and became one of the most influential figures in French feminism. Today, Delphy remains a prominent and controversial feminist thinker, a rare public voice denouncing the racist motivations of the government's 2011 ban of the Muslim veil. Castigating humanitarian liberals for demanding the cultural assimilation of the women they are purporting to "save," Delphy shows how criminalizing Islam in the name of feminism is fundamentally paradoxical.

Separate and Dominate is Delphy's manifesto, lambasting liberal hypocrisy and calling for a fluid understanding of political identity that does not place different political struggles in a false opposition. She dismantles the absurd claim that Afghanistan was invaded to save women, and that homosexuals and immigrants alike should reserve their self-expression for private settings. She calls for a true universalism that sacrifices no one at the expense of others. In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, her arguments appear more prescient and pressing than ever.

Separate and Dominate is Delphy's manifesto, lambasting liberal hypocrisy and calling for a fluid understanding of political identity that does not place different political struggles in a false opposition. She dismantles the absurd claim that Afghanistan was invaded to save women, and that homosexuals and immigrants alike should reserve their self-expression for private settings. She calls for a true universalism that sacrifices no one at the expense of others. In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, her arguments appear more prescient and pressing than ever.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Separate and Dominate by Christine Delphy, David Broder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Discrimination & Race Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Who’s Behind the ‘Others’?

The texts in this book have one objective in common. That is, to elaborate a materialist approach to not only oppression and marginalization, but also domination and normality. These themes are pairs of opposites; we can’t have the one without the other. Some will say that we’ve heard all this before. But it is a lesson that has not been widely received. So here I am insisting on what I have been repeating over the years, principally as regards the opposition between women and men: this division is constructed at the same time as the hierarchy between them, and not before. It is at the same moment, in the same movement, that a division or distinction is both created and created as a hierarchy, opposing the superior to the inferior.

As I have already written elsewhere,1 this is a theory of the divisions produced in society. These divisions are both dichotomous and comprehensive. If you are not in one group, you are in the other.

The other – and even the Other, with a capital O – is often invoked as an explanation of the phenomena that I’m addressing here: the oppression of women, of non-whites and of gays. In this view, in order to put an end to discrimination based on gender, race and sexuality, it is necessary – and sufficient – to decide once and for all to ‘accept the Other’.

Indeed, we often hear, in newspaper columns or in the writings of philosophers, sociologists and other scholars, that the hierarchy in our society is due to the ‘rejection of the Other’. Except when it comes to the opposition between ‘capitalists’ and ‘workers’. That is not to say that there was never a time when that question, too, was treated like this: but a hundred and fifty years ago Marxism replaced this with a materialist analysis.

Since 1975, when I wrote ‘Pour un féminisme matérialiste’,2 I have opposed all idealist ‘explanations’ of the oppression of women, instead advancing a materialist approach. And the thesis that claims that human beings cannot stand ‘difference’ is a thesis on human nature: an essentialist thesis and, therefore, an idealist one. This approach does not only apply to the oppression of women; and here I also present texts dealing with the oppression of non-whites and of gays.

What these three oppressions have in common is that each of them divides the whole of society, the whole population, into two categories, into two camps. But each of them sets its own line of separation, dividing the same population with which we started – let’s say, the population living on French territory – in a different manner. Since there is a different principle behind each of these three divisions, the dominant and dominated groups that these principles constitute are different in each of the three cases. But since we’re always beginning from the same population, and given that each of these divisions is exhaustive, each of these dominant and dominated groups is in turn dissected by the second and then the third principle of division. So a person could be in the dominant group according to one division and the dominated group according to another, and then again belong to the dominant group according to the third division; or be dominant in all three cases, or always in the dominated group.

The end result of these processes is that each person is necessarily defined as a woman or a man, a non-white or a white, a homosexual or a heterosexual.

The articulation, imbrication or interlinking of these different oppressions, and the set of combinations resulting from their criss-crossing, are one of the main focuses of sociology and in particular of feminist sociology. But they are not the object of this collection. In bringing together texts devoted to oppressions based on gender, race and sexuality, what I want to emphasize is the similarity among the operations that give priority to one group and stigmatize another.

I also want to show not only that the problematic of the Other fails to explain sexism, racism, homophobia, or any other social hierarchy, but that it presupposes the existence of such hierarchies.

The object of this collection, then, is principally to show that hatred of ‘the different’ is not a ‘natural’ trait of the human species. I do so firstly by examining the arbitrary fashion in which the Western tradition – formalized in philosophy – has posed this hatred as a universal, constituent element of the human psyche and invented the concept of the ‘Other’. Secondly, I show that this other is socially constructed through concrete material practices, including ideological and discursive ones – it does not express some hypothetical ‘human nature’, which is an ideological concept.

These texts share the same problematic, but they differ in their very varied style and format, which reflect the diversity of the circumstances in which they were produced. Some were academic papers for conferences or journals, while others were interventions in political meetings, articles for newspapers, or submissions to government committee hearings.

The concept of the Other as an invention of the Western tradition

There are two reasons why ‘hatred of the different’ cannot explain the existence of stigmatized groups in our societies.

The first is that an explanation in terms of ‘rejection of the other’ is a psychologizing approach; that is, it transposes theories based on the individual psyche onto the plane of phenomena regarding how societies function.

The second is that this psychology – this theory of the individual psyche – is itself part of a particular, Western philosophy that addresses the question of the ‘other person’ from the viewpoint of the ‘I’. Let’s begin with this second reason.

I. Even to describe the question in the manner that Western philosophy has historically addressed it immediately brings the ‘I’ to the fore. When I speak of philosophy, I mean the invisible, subterranean foundations of the worldview [Weltanschauung] that a culture shares in common.3 With that caveat, we can say that ever since Plato, the Western worldview – as it’s been expressed by the people credited with revealing these foundations, the ‘philosophers’ – is firstly a reflection on the self, and after that a reflection on the world. However, philosophy does recognize the world’s existence, and it is thus fully justified in examining what viewpoint it assumes as its basis for looking out at the world – this viewpoint being the ‘I’. But in this philosophy, the ‘I’ is alone. All by itself and constitutive. It does not pose the question of the other person, because this other person is not necessary but superfluous. The ‘I’ embodies consciousness, and if there is one human consciousness that can see the world and see itself seeing it, there is no need for any other consciousness. This first, singular consciousness – the only necessary one – tells us ‘I think therefore I am’ (Descartes) but never asks what the conditions of possibility of its thinking are.

For example, notwithstanding Descartes’s hilarious description of his childhood in his first Meditation, he seems never to have been brought into the world or brought up; language came to him just like that, and he learnt to write without anyone teaching him – and we don’t know why he wrote, because he was apparently not writing for anyone. He was perfectly indifferent to the conditions of possibility for his existence and of him sitting down one fine day to write ‘Cogito ergo sum’ – and he wasn’t hungry or thirsty or cold – some invisible entities took care of that – he didn’t give them half a thought. More than one academic’s wife will recognize her husband in this portrait … So it is a philosophy of the dominant, for whom material life plays out to their benefit – the necessities of their survival are fulfilled, but externally to them. This disdain for the conditions of possibility of one’s own existence and own thinking is taken yet further, with the denial of society as a whole. Well, no individual can exist outside of society. There can be no human without a society, and no thought without language; the very existence of individuals indispensably depends on there being some collectivity, even if it is just a few dozen people. The very notion of the individual is linguistic, and therefore social. The hyperindividualism of Western philosophy borders on solipsism and autism. It cannot provide the foundation for a psychology worthy of the name – which must take into account the conditions of possibility for not just this or that individual psyche, but the psyche as such.

And the notion of the Other as a pre-existing and, in short, ‘natural’ reality comes to us precisely from this erroneous psychology, one of the major constituent parts of Western philosophy. In all this Western tradition, formulated and then built up by the philosophers, it is in Hegel that the other person appears as a ‘philosophical question’ that we need to account for. Here, this other appears as a threat to the expression of the subject, as Sartre later remarked by adopting his famous formula: ‘Each conscience seeks the death of the other.’

As such, Western philosophy, which claims to speak the truth about human beings independently of their time or place, without needing to specify their concrete situations in a given society, decrees that the ‘other person’ is dangerous. This philosophy tells us that its object – human beings in general – can only be alarmed by the existence of others, and if it were possible would gladly do without them. For the Western tradition, to think the human condition means thinking it on the basis of a human being who is alone on this Earth and would prefer things to stay that way.

This philosophy is thus simultaneously a psychology, because it describes or predicts reactions (of worry faced with the other person) and desires (of solitude). And as a psychology, this theory is not just solipsist: it’s flat-out crazy. After all, as Francis Jacques writes in a brilliant synthesis, it ultimately ends up saying: ‘If a being exists, what need is there for beings? If one exists, what need is there for many?’4 It is crazy in that it denies the reality of the world of human beings (and, besides, of all living things) including the subject of the consciousness that it is discussing. Today orthodox psychoanalysis (Freud and Lacan) embodies the paradigmatic expression of this Western vision, this having become the basis not only of the psychology taught in French universities but also of the ‘pop science’ most widespread among the general public. It has arrived at the extreme limit of solipsism: posing the existence of an ‘intra-psychic reality’ that has nothing to do with what happens or has happened in individuals’ lives.

II. But now we come to the first reason why explanations in terms of ‘rejection of the Other’ are inadequate. Indeed, whatever the validity of psychological theories on the plane on which they claim to operate (the functioning of the individual psyche), we can in no case use them as our basis for explaining how groups relate to one another.

After all, even if we were here dealing with a materialist psychology in which the other is always-already present in the consciousness of each person, in this passage from psychology to sociology there is an epistemologically unjustifiable change of scale.

Scientific sociology constantly runs into the psychologizing reductionism of spontaneous psychology, which tautologically explains police violence in terms of the brutality of policemen and domestic violence in terms of bad husbands. In reality, of course, it is the organization of society that not only makes individuals violent but also allows them to be violent – and not individual traits pre-existing society.

But why is spontaneous sociology founded on such a false, individualizing and essentialist vision, if not because this vision, which implies that the relations among people are not organized by society, is the very ideology of our society?

Scientific understanding recognizes the methodological inadmissibility of transposing the level of individual consciousness onto the level of society, and of understanding groups and the relations among them as a large-scale reflection of mental processes proper to individuals or the relations among individuals. Society is not a big individual; it can be explained only in terms of social processes, which are not of the same order as psychological processes.

So even if our individual psychology were of the type described by Western philosophy, and even if this psychology dictated that each of us feared the ‘other person’, this would be of no help in explaining why entire groups see and name other entire groups as ‘others’.

However, this is what happens when we are constantly exhorted – as individuals but also as a set of individuals, as a group called ‘Us’ – to ‘accept the Other’ and thus put an end to sexism, racism and homophobia.

The collective creation, the organization that is society, prevails over individuals and pre-exists each of them – because we are born to an already existing society. Society cannot however be conceived as a plus-size individual, nor as the sum of the individuals within it. It does need them – no society can survive without its members – and even more so, they need it, because a human being cannot be human, or even simply survive, outside of society. Yet this interdependence does not imply that these two phenomena have the same rules of functioning. Society is not an individual. Even if we can accept that each individual, confined within her own skin and her physiological and psychological functioning, perceives the other person as distinct from her – which certainly doesn’t mean fearing and rejecting them! – the same cannot be said of society. Society cannot have a problem with the ‘other’ person, because it has no psyche: the expression ‘collective consciousness’ is a metaphor.

‘The other par excellence is the feminine, through which a world behind the scenes extends the world.’

– Emmanuel Lévinas5

Which is something to think about for all those Others who imagine the ‘Ones’6 are messing around when they don’t treat them as human beings. Let’s go back to the exhortation to accept the Other, or ‘otherness’, or ‘difference’. This Other is rather vague: it could mean other people who have the same God or humanism as me, even if it’s not apparent at first sight. It could also be a whole bunch of others, and in general, it is that: it is a stigmatized group whose stigmatization goes unmentioned.

We think we understand, because we call them ‘the Other’ and because we know that we ‘struggle to accept the other’. This discourse is such a commonplace that it is impossible to go a day without reading or hearing it, and yet it also contains something of a mystery. Everyone seems to know who these Others are; everyone talks about them, but they never speak.

So what discourse does the Other (singular or plural) appear in? In the form of a discourse addressed to people who are not Others. But where, then, do these Others come from? Are there Others, and if so, why? In order to clear up this mystery, we have to go back to the exhortation to accept them. Who is being invited to accept the Others? Not the Others, evidently. And who is making this call? We don’t know their name, but we do know that they’re not an Other. It is not the Other who asks for acceptance. But as well as not telling us their own name, they don’t tell us who the ‘Us’ being addressed are. So behind this Other that we’re always hearing about – without this Other ever speaking – is hidden another person, who speaks all the time, but who we never hear about: the ‘One’, who speaks to ‘Us’. Th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction to the English-Language Edition

- 1: Who’s Behind the ‘Others’?

- 2: For Equality: Affirmative Action Over Parity

- 3: Republican Humanitarianism against Queer Movements

- 4: A War Without End

- 5: Guantánamo and the Destruction of the Law

- 6: A War for Afghan Women?

- 7: Against an Exclusionary Law

- 8: Race, Caste and Gender in France

- 9: A Movement: What Movement?

- 10: Anti-sexism or Anti-racism? A False Dilemma