- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

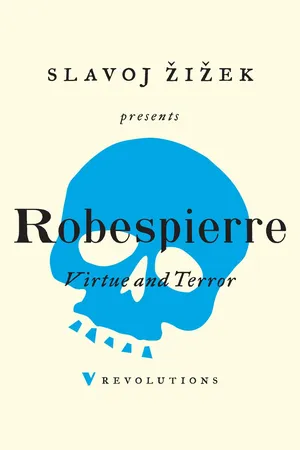

Virtue and Terror

About this book

Robespierre's defense of the French Revolution remains one of the most powerful and unnerving justifications for political violence ever written, and has extraordinary resonance in a world obsessed with terrorism and appalled by the language of its proponents. Yet today, the French Revolution is celebrated as the event which gave birth to a nation built on the principles of Enlightenment. So how should a contemporary audience approach Robespierre's vindication of revolutionary terror? Zizek takes a helter-skelter route through these contradictions, marshaling all the breadth of analogy for which he is famous.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

ROBESPIERRE AT THE

CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY

AND THE JACOBIN CLUB

Elected as a deputy to represent the Artois region at the Estates-General in April 1789, Robespierre spoke frequently in the Constituent Assembly. Alongside this, he was one of the first members of the Jacobin Club, where he made some of his most famous speeches.

The Legislative Assembly succeeded the Constituent Assembly in October 1791. The former deputies were excluded from the new assembly by a motion proposed by Robespierre himself.

Whilst many of these former deputies returned to the provinces and no longer played major political roles, Robespierre stayed in Paris at the tribune of the Jacobin Club.

1

ON VOTING RIGHTS FOR

ACTORS AND JEWS

23 December 17891

On 23 December, Robespierre intervened in the Constituent Assembly against Abbé Maury who had denounced the mores of actors. The latter were mostly excommunicated from the church under the Ancien Régime and deprived of any status defining their social position.Two days earlier, Clermont-Tonnerre2 had proposed that one’s profession and faith should not render one ineligible for public office.On 24 December, non-Catholics were conceded the right to hold public office, but Jews were not included. The latter gained the same rights as other citizens only on 27 September 1791.

Every citizen fulfilling the conditions of eligibility that you have prescribed has the right to public office. When you discussed those conditions, you were dealing with the great cause of humanity. The previous speaker tried to make three different causes out of a few specific circumstances. All three are contained in the principle, but for the sake of reason and truth, I am going to examine them briefly.

It will never be successfully claimed in this Assembly that a necessary function of the law can be stigmatized by the law. That law has to be changed, and the prejudice no longer having any basis will disappear.

I do not believe that you would need a law on the subject of actors. Those who are not excluded are eligible. It was good, however, that a member of this Assembly came to make a noise in favour of a class too long oppressed. Actors will merit public esteem more when an absurd prejudice no longer resists their obtaining it: then, the virtues of individuals will help to purify the shows, and theatres will become public schools of principles, good morals and patriotism.

Things have been said to you about the Jews that are infinitely exaggerated and often contrary to history. How can the persecutions they have suffered at the hands of different peoples be held against them? These on the contrary are national crimes that we ought to expiate, by granting them imprescriptible human rights of which no human power could despoil them. Faults are still imputed to them, prejudices, exaggerated by the sectarian spirit and by interests. But to what can we really impute them but our own injustices? After having excluded them from all honours, even the right to public esteem, we have left them with nothing but the objects of lucrative speculation. Let us deliver them to happiness, to the homeland, to virtue, by granting them the dignity of men and citizens; let us hope that it can never be policy, whatever people say, to condemn to degradation and oppression a multitude of men who live among us. How could the social interest be based on violation of the eternal principles of justice and reason that are the foundations of every human society?

2

ON THE SILVER MARK

April 17911

The following speech was never delivered but was printed and discussed in the popular societies.Robespierre is here opposing the distinction between ‘passive’ and ‘active’ citizens whereby only those able to pay a contribution equivalent to three days’ work were eligible to vote. Moreover, only those able to pay a high tax – that is, a silver mark – were eligible to run for election.Out of seven million (male) citizens, three million were thus excluded and considered as ‘passive’. The Constitution of 1791 recognized this distinction, thus installing a qualified or restricted form of suffrage.Quasi-universal male suffrage was only achieved with the fall of the monarchy and the election of the Convention.

Gentlemen,

I was in doubt, for a time, as to whether I should offer you my thoughts on some measures you appeared to have adopted. But I saw that it was a question of either defending the cause of the nation and of liberty, or betraying it by remaining silent; and I hesitated no longer. I even undertook this task with a confidence rendered all the more firm, in that the imperious passion for justice and the public good that imposed it on me was held in common with yourselves, and that it is your own principles and your own authority that I invoke in their favour.

Why are we gathered here in this temple of law? Doubtless, to enable the French nation to exercise the imprescriptible rights that belong to all men. Such is the object of every political constitution. It is just, it is free, if it fulfils that object; it is only an attack on humanity if it counters it.

You yourselves acknowledged this truth in a striking manner when, before starting your great work, you decided that these sacred rights, which are, as it were, the eternal foundations on which it should be based, ought to be solemnly stated.

‘All men are born and remain free, and equal before the law.’

‘Sovereignty resides essentially in the nation.’

‘The law is the expression of the general will. All citizens have the right to contribute to its formation, either in person or through their freely elected representatives.’

‘All citizens are eligible for all public offices, without any distinction other than their virtues and talents.’2

Those are the principles you established: it will be easy now to assess the provisions I mean to oppose; all that is needed is to compare them with those invariable rules of human society.

Now, firstly: is the law the expression of the general will, when the greater number of those for whom it is made cannot contribute to its formation in any way? No. But to deny to all those who do not pay a contribution equal to three working days the right to choose the electors intended to name the members of the Legislative Assembly, what else is that but ensuring that the majority of the French are absolutely excluded from the formation of the law? That provision is thus essentially anti-constitutional and antisocial.

Secondly: are men equal in their rights, when some enjoy exclusively the right to stand for election as members of the legislative body or other public institutions, others simply the right to appoint them, and the rest are deprived of all these rights? No. Such, however, are the monstrous differences established between them by decrees that render a citizen active or passive; or half active or half passive, depending on the various degrees of fortune enabling an individual to pay three working days, or ten days of direct taxation, or a silver mark. All these provisions are therefore essentially anticonstitutional and antisocial.

Thirdly: are men eligible for all public posts without distinction other than their virtues and talents, when the inability to discharge the required contribution disqualifies them from all public posts, whatever their virtues and talents may be? No; all these provisions are therefore essentially anticonstitutional and antisocial.

Fourthly: lastly, is the nation sovereign, when the greater number of the individuals who compose it are robbed of the political rights that constitute sovereignty? No; nevertheless you have just seen that these same decrees strip them away from the greater part of the French. What then would your Declaration of Rights be, if these decrees could survive? An empty formula. What would the nation be? Enslaved; for liberty consists in obeying laws voluntarily adopted, and servitude in being forced to submit to an outside will. What would your constitution be? A veritable aristocracy. For aristocracy is the state in which one portion of the citizens is sovereign and the rest subjects. And what an aristocracy! The most unbearable of all, that of the rich.

All men born and domiciled in France are members of the political society called the French nation, in other words French citizens. That is what they are by the nature of things and by the main principles of the law of nations. The rights attached to this title depend neither on the fortune each individual possesses, nor on the amount of taxation to which he is subject, because it is not tax that makes us citizens; the quality of citizen only obliges him to contribute to the common expenditure of the state, according to his abilities. Now you can give laws to the citizens, but you cannot annihilate them.

The supporters of the system I am attacking have noticed this truth themselves since, not daring to contest the quality of citizen in the case of those they were disinheriting politically, they limited themselves to evading the principle of equality which it necessarily presupposes, by making a distinction between active citizens and passive citizens. Counting on the ease with which men are governed by words, they tried to put us off the scent by proclaiming, in this new expression, the most manifest violation of the rights of man.

But who could be so stupid as not to see that these words can neither change the principles, nor resolve the difficulty; since declaring that such citizens will not be active, and saying that they will no longer exercise the rights attached to the title of citizen, amount to exactly the same thing in the idiom of these subtle politicians. Now I will always ask them by what right they can thus strike their fellow-citizens and constituents with inactivity and paralysis: I will not stop clamouring against this insidious and barbaric locution, which will defile both our code and our language unless we hasten to erase it from both of them, in order that the word liberty does not itself become meaningless and derisory.

What shall I add to such obvious truths? Nothing for the benefit of the nation’s representatives, whose opinions and wishes have already anticipated my demand: it just remains for me to answer the deplorable sophistries with which the prejudices and ambitions of a certain class of men strive to shore up the disastrous doctrine I am fighting; it is those men alone that I am now going to address.

The people! folk who have nothing! The dangers of corruption! The example of England, of peoples supposed to be free; these are the arguments deployed against justice and reason.

I ought only to answer with a word or two: the people, that multitude of men whose cause I am defending, have rights that come from the same origin as your own. Who gave you the power to take them away?

General practicality, you say! But is there nothing practical in what is just and honest? And does not that eternal maxim apply above all to social organization? And if the purpose of society is the happiness of all, the conservation of the rights of man, what should we think of those who want to base it on the power of a few individuals and the degradation and hopelessness of the rest of the human race! What then are these sublime politicians, who applaud themselves for their own genius, when by means of laborious subtleties they have at last managed to substitute their vain fantasies for the immutable principles graven in the hearts of all men by the eternal legislator!

England! ha! What good are they to you, England and its depraved constitution, which may have looked free to you when you had sunk to the lowest degree of servitude, but which it is high time to stop praising out of ignorance or habit! Free peoples! Where are they? What does the history of those you honour with this name show you? Other than aggregations of men more or less remote from the paths of reason and nature, more or less enslaved, under governments established by chance, ambition or force? So was it to copy slavishly the errors or injustices that have long degraded the human species that eternal providence called on you, on you alone since the world began, to re-establish on earth the empire of justice and liberty, in the heart of the brightest enlightenment ever to have illuminated public reason, amid the almost miraculous circumstances providence has been pleased to assemble, to supply you with the power to restore to mankind its original happiness, virtue and dignity?

Do they really feel the full weight of that sacred mission, those who, in answer to our justified complaints, are content merely to say coolly: ‘With all its faults, our constitution is still the best that has ever existed.’ Was it then so that you might nonchalantly leave in that constitution essential faults, destructive of the basic foundations of the social order, that twenty-six millions of men put the formidable weight of their destinies in your hands? Would it not be said that the reform of a great number of abuses and several useful laws would be so many favours granted to the people, enough to make it unnecessary to do any more in its interests? No, all the good you have done was a rigorous duty. The omission of good which you can do would be a breach of trust, the harm you would be doing a crime of lèse-nation and lèse-humanity. There is more: unless you do everything for liberty, you have done nothing. There are no two ways of being free: one must be entirely free, or become a slave once more. The least resource left to despotism will soon restore its power. What am I saying! it surrounds you already with its blandishments and its influence; soon it could overwhelm you with its force. You are pleased to have attached your names to a great change, but are not much concerned as to whether it is great enough to ensure human happiness. Make no mistake: the sound of the eulogies that astonishment and frivolity are causing to clamour about you will soon die down; posterity, comparing the greatness of your duties and the immensity of your resources with the fundamental flaws in your work, will say of you, with indignation: ‘They could have made men happy and free; but they did not want to; they were unworthy of it.’

But, say you, the people! People who have nothing to lose! Will then be able, like us, to exercise the rights of citizens.

People who have nothing to lose! how unjust and false it is in the eyes of truth, that language of delirious arrogance!

The people of whom you speak are apparently men who live, who subsist, in society, without the means to live and subsist. For if they are provided with those means they have, it seems to me, something to lose or to preserve. Yes, the rough garments that clothe me, the humble garret to which I purchase the right to withdraw and live in peace; the modest wage with which I feed my wife, my children; these things, I admit, are not lands, carriages, great houses; all of them amount to nothing perhaps, to those accustomed to luxury and opulence, but they are something to ordinary humanity: they are sacred property, beyond doubt as sacred as the glittering domains of wealth.

What am I saying! My liberty, my life, the right to obtain safety or vengeance for myself and my loved ones, the right to repel oppression, to exercise freely all the faculties of my mind and heart, all these good things, so sweet, the first of those that nature has allotted to mankind, are they not entrusted, like yours, to the guardianship of the law? And you say I have no interest in this law; and you want to strip me of the share I should have, like you, in the administration of the state, for the sole reason that you are richer than I am! Ah! if the balance stopped being equal, should it not tend to favour the less prosperous citizens? The law, the public authority: is it not established to protect weakness against injustice and oppression? It is thus an offence to all social principles to place it entirely in the hands of the rich.

But the rich, the powerful, have reasoned differently. Through a strange abuse of words, they have restricted the general idea of property to certain objects only; they have called only themselves property owners; they have claimed that only property owners were worthy of the name of citizen; they have named their own particular interest the general interest, and to ensure the success of that claim, they have seized all social power. And we! oh human weakness! we who aspire to bring them back to the principles of equality and justice, it is still on the basis of these absurd and cruel prejudices that we are seeking, without being aware of it, to raise our constitution!

But what after all is this rare merit of paying a silver mark or some other tax to which you attach such high prerogatives? If you give the public Treasury a contribution more considerable than mine, is it not for the reason that society has given you greater pecuniary advantages? And, if we want to pursue this idea, what is the source of that extreme inequality of fortunes that concentrates all the wealth in a small number of hands? Does it not lie in bad laws, bad governments, and finally all the faults of corrupt societies? Now, why should those who are the victims of these abuses be punished again for their misfortune, by losing the dignity of being citizens? I envy not at all the advantageous share you have received, since this inequality is a necessary or incurable evil: but at least, do not take from me the imprescriptible property of which no human law can strip me. Indeed, allow me to be proud sometimes of an honourable poverty, and do not seek to humiliate me with the vainglorious pretension that the quality of sovereign is reserved for you, while I am left only with that of subject.

But the people! … the corruption!

Ah! stop, I say stop profaning the touching and sacred name of the people, by linking it with the idea of corruption. What is a person who, among men equal in rights, dares to declare his fellows unworthy of exercising theirs, and to take them away for his own advantage! And surely, if you allow yourselves to base such a conviction on assumptions of corruptibility, what a terrible power you are assuming over humanity! Where will your proscriptions end?

But is it really on those who do not pay the silver mark that they should fall, or on those who pay much more? Yes, in spite of all your bias in favour of the virtues that wealth brings, I dare say that you would find them as much in the class of the least-monied citizens as in that of the most opulent! Do you really believe in all honesty that a hard and laborious life produces more faults than softness, luxury and ambition? And have you less faith in the probity of our artisans and ploughmen, who under your tariff will almost never be active citizens, than tax-farmers, courtiers, those you used to call great lords, who under the same tariff would be active six hundred times over? I want one day to avenge those you call the people for these sacrilegious calumnies.

So are you fit to appreciate the people, and to know men, you who since reaching the age of reason have judged them only by the absurd ideas of despotism and feudal arrogance; you who, accustomed to the bizarre jargon invented by them, found it easy to denigrate the greater part of the human race with the words rabble and populace; you who have revealed to the world that there were people of no birth, as if all the men a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Robespierre, or, The ‘Divine Violence’ of Terror

- Suggested Further Reading

- Glossary

- Chronology

- Translator’s Note

- Part One: Robespierre at the Constituent Assembly and the Jacobin Club

- Part Two: In the National Convention

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Virtue and Terror by Maximilien Robespierre, Jean Ducange, John Howe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & French History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.