- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Soviet Model and Underdeveloped Countries

About this book

This book constructs the model of economic development implicit in the historical experience of the Soviet Union, and the agricultural, industrial, and social strategies followed are shown to fit into a logical and coherent pattern. Those strategies are then evaluated for the positive and negative answers they hold for underdeveloped countries today.

Originally published 1969.

A UNC Press Enduring Edition -- UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Originally published 1969.

A UNC Press Enduring Edition -- UNC Press Enduring Editions use the latest in digital technology to make available again books from our distinguished backlist that were previously out of print. These editions are published unaltered from the original, and are presented in affordable paperback formats, bringing readers both historical and cultural value.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

THE MODEL

I. INTRODUCTION

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

The economic development of underdeveloped countries is the “paramount practical problem”1 confronting economists in the second half of the twentieth century. This is not a new problem; underdeveloped countries have always existed. But it is only in the last twenty years that economic development has captured the attention of economists and statesmen alike. Simon Kuznets gives three reasons for this recent emphasis. First is the realization that international division of labor has not brought the benefits expected by nineteenth-century economic theory. Second, the pressure for economic development exerted by the newly independent countries suggests that lack of freedom from want in underdeveloped countries may well mean lack of freedom from fear in developed countries. The third and probably most important reason “is the emergence of a different social organization which claims greater efficiency in handling long-term economic problems”2—the socialist economy of the Soviet type.

To the extent that one can estimate the historical significance of any recent development, the U.S.S.R. seems to have opened a new chapter in world economic history—the era of forced economic growth in agriculturally overpopulated countries. The U.S.S.R. produced the world’s first example of rapid economic development centrally planned and directed; and this example—that is, both Soviet strategy and planning procedure—excercises today a deep influence on the underdeveloped countries. Nicolas Spulber has cogently explained why the Soviet experience has captured the imagination of a great part of the new Asian, African, and Latin American intelligentsia.

The crucial importance within these countries of the relationship between a small industrial and an overwhelming agricultural sector; the decisive importance of massive investments for developing certain new domestic industries, and the possible advantages accruing from the adoption of the most advanced technology in at least some key processes; the possibility of automatically fulfilling “realistic” capital formation targets by planning in physical terms, in countries with defective statistical information and unresponsive price mechanisms—all these render the Soviet planning model . . . extremely adaptable to backward countries. The antipathy to private enterprise, often identified with colonialism; the currently wide acceptance of the idea that the government necessarily assumes an important role in the consumption, allocation, and management of the country’s resources; and finally, the almost charismatic character of the newly independent states render the early Soviet-type planning theory and methods attractive for even non-communist underdeveloped countries.3

There are, of course, factors restraining underdeveloped countries from adopting a program of forced industrialization along Soviet lines. Some of these are “. . . the fears of the upper and middle classes faced with a revolutionary upheaval; the dislike of totalitarian methods felt by part of the . . . intelligentsia educated in the West; and above all the pressure of Western creditors.”4

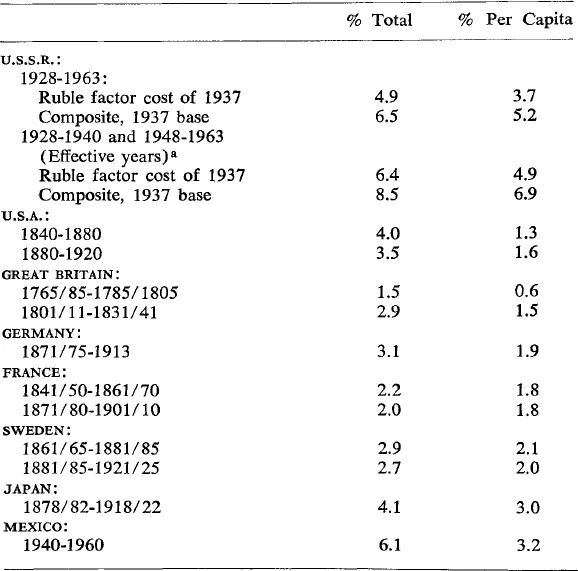

Economic growth in the Soviet Union has been very great. Indices of industrial production and agricultural production will be presented in the following chapters. At this point only statistics on gross national product will be used to illustrate the success of the Soviet model of economic development.

Table 1-1 clearly brings out the tempo of Soviet economic development. Growth rates of this magnitude have had a profound effect upon the leaders of underdeveloped countries.

Since the specifics of Soviet industrial development were more the product of improvisation in the face of various pressing imperatives than of deliberate design, we must look to Soviet reality rather than to the writings of Marx, Lenin, or Stalin to find the causes of this growth. Therefore, the present study attempts to construct the model of economic development implicit in the historical experience of the U.S.S.R. and to evaluate it in that context. No attempt is made to prove that alternative models are inadequate or that the Soviet model is a sufficient and necessary condition of rapid economic growth. Rather, the less ambitious attempt is made to demonstrate that the Soviet model can provide some useful lessons for underdeveloped countries.

TABLE I-1

Average Annual Growth Rates of Gross National Product in Selected Countries

Sources:

The index for the U.S.S.R. was spliced together from three sources. For 1928-55, Abram Bergson, The Real National Income of Soviet Russia Since 1928 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961), p. 217. The separate weighting systems apply only through 1955. For 1955-60, U.S. Congress, Joint Economic Committee, Dimensions of Soviet Economic Power, 87th Cong., 2nd Sess., 1962, p. 75. For 1960-63, U.S. Congress, Joint Economic Committee, Current Economic Indicators for the U.S.S.R., 89th Cong., 1st Sess., 1965, p. 13. For the other countries: Simon Kuznets, Economic Growth and Structure (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1965), pp. 305-7; Phyllis Deane and W. A. Cole, British Economic Growth: 1688-1959 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964), pp. 80, 170, 172; Robert L. Bennett, The Financial Sector and Economic Development (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1965), p. 187.

aOmitting the war and reconstruction years of 1940-48.

THE PROBLEM OF METHOD

As the word is used here, “Soviet” means primarily the Soviet Union. The experience of the other Soviet-type economies is used only to provide modifications of the basic model. The term “model” does not mean a detailing of every strategy, correct and incorrect, that was used by the Soviet Union. Rather it is an abstraction of the essentials from the Soviet experience modified by the later experience of the various socialist countries. Except for the excellent article by John Montias5 this concept of the “Soviet Model” has not been followed on the subject.6

It is possible, and indeed necessary, to abstract from the secondary attributes of the individual cases and to concentrate on their essential common characteristics. This approach has always been the primary tool of all analytical effort—whether it be Marx’s “pure capitalism,” Marshall’s “representative firm,” or Weber’s “ideal type.” That the resulting “model” does not take into account every peculiarity of the given case does not invalidate its usefulness. Its value lies in the establishment of a framework which gives interpretation and meaning to the facts and descriptions assembled by quantitative research.

There is no question, therefore, that a theoretical approach must be used in analyzing the process of economic development. Rather the important question to be answered is what theory should be used. “Theory is in the first and last place a logical file of our factual knowledge pertaining to a certain phenomenological domain. . . . To each theory, therefore, there must correspond a specific domain of the reality.”7 In determining the proper domain of a theory the question arises whether an economic theory which successfully decribes one economic system, say capitalism, can be used to successfully explain another economic system, say feudalism or socialism. This problem seldom bothers the physical sciences for no evidence exists that the behavior of matter varies with time or social system. In contrast, human societies vary widely, with both time and locality. Some would argue that these variations are only different instances of a unique archetype and that consequently all social phenomena can be encompassed by a single theory. It is sufficient to point out that when “. . . the theories constructed by these attempts do not fail in other respects, they are nothing but a collection of generalities of no operational value whatever. . . . For an economic theory to be operational at all, i.e. to be capable of serving as a guide for policy, it must concern itself with a specific type of economy, not with several types at the same time.”8

Every theory is a model of a particular economic system because it must assume certain institutional and cultural traits. Thus, orthodox theory (neoclassical and Keynesian) assumes that individuals act hedonistically, that entrepreneurs seek to maximize cash profits, and commodities can be exchanged on the market at uniform prices and none exchanged otherwise. When it is realized that for economic theory an economic system is characterized exclusively by institutional traits, it becomes obvious that orthodox theory is not valid as a whole for the analysis of a noncapitalist economy. A particular proposition of the theory may be valid for a noncapitalist economy, but its validity must be established anew, either by empirical evidence or by logical derivation from the new model. Even the analytical tools developed by orthodox theory cannot be used indiscriminately in the analysis of other economies. Most analytical tools are hard to transplant from one economic theory to another. This is not to say, however, that orthodox theory does not provide useful patterns for asking the right kind of questions and for seeking the relevant constituents of any economic reality.9

Further problems arise in attempting to use orthodox economic theory to analyze the process of economic development. Great strides have been made in the study of economic growth in the last few years. But a distinction should be made between economic growth, analyzed in terms of changes in the value of economic parameters in given institutional conditions, and economic development, when changes in the value of economic parameters are accompanied or even preceded by institutional changes. Orthodox theory is a more efficient instrument for analysis of the quantifiable short-run determinants of income than of the process of economic development. In income analysis or even growth theory, long-run factors of a socio-political nature may be held constant, regarded as given. Economic development, however, is a process which affects not only purely economic relations but the entire social, political, and cultural fabric of society. In the dynamic world of economic development, the data usually impounded in ceteris paribus are in constant motion as factors making for change.

Because the very essence of economic development is rapid and discontinuous change in institutions and the value of economic parameters, it is impossible to construct a rigorous and determinate model of the process. An economist must be willing to settle for less. Henry Bruton expresses the problem well when he says that “elegance and rigor are important attributes of effective economics, but they must take second place to relevance and applicability. The student or teacher who likes his economics in the form of neat theorems is alerted that few have been found in the field of technology, education, population growth, and a dozen other aspects of development.”10 Stuart Bruchey goes further and argues that the more rigorous the model, the higher its degree of technical success may be, but the greater its inability to explain economic development.11Such a model necessarily omits too many of the most significant variables in economic development. It follows that an inquiry into the causal origins of economic development ought not to commence with a highly generalized, highly abstract model to frame the analysis. If a rigorous and determinate model is not utilized to study the process of economic development, a less rigorous but more richly textured model which accounts for the most important socioeconomic variables must be constructed. To this writer the use of economic history, together with theoretical logic, holds out the greatest prospect for success.

Economic History and Economic Development. It has been said that scholars “. . . come to Economic History either as historians in search of a soul, or as economists in search of a body.”12 Many economic theorists are too fond of clever abstractions and too dependent on arbitrary concepts and models which are empty of empirical content and possess little, if any, relationship to the mutability of historical reality. Many historians allow their aversion to orthodox theory to prejudice their research and writing to the point where they become mere “fact grubbers” and “story tellers.” The problem lies in a confusion between a “theoretical approach” and particular theories and concepts. A particular theory can be useful or useless, depending on the problem addressed. A “theoretical approach” is an essential step toward comprehension of hi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Part One: The Model

- Part Two: An Application of the Soviet Model: Soviet Central Asia

- Part Three: Conclusion

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Soviet Model and Underdeveloped Countries by Charles K. Wilber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.