![]()

1

RIVERSHADE

INTRODUCTIONS

In April 1925, a group of American Protestant missionaries in China erected a large tent in the middle of the city where they were stationed in preparation for celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the beginning of their work in that community. The celebration in itself would not be worthy of much comment. This particular station was not a pioneer in the American mission effort in China; it was, in fact, established fairly late in the game. Nor were any of its personnel well-known members of the mission force in China.

What is significant about this event is the participation in the celebration of the city’s notables, including the “mayor” and many prominent businessmen and scholars. They presented the missionaries with a number of gifts and lauded their contributions to the welfare of the city. How had these foreigners earned such praise and esteem from their hosts at a time when nationalistic sentiment was running rampant in China?

The tale is a fascinating one and justifies a careful study of the life of this particular mission station in the city of Jiangyin1 in the eastern coastal province of Jiangsu. But the history of this station provides more than a good story. An in-depth study of this fairly typical American missionary community can reflect more broadly on the nature of American interaction with China during a half-century of momentous change, from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century, placing local history in the context of national and international history.

Within the limited scope of this study, my central concern is whether and in what ways this missionary community fit in with the local Chinese society. As the opening account indicates, the Jiangyin missionaries at one point had achieved a measure of integration with their Chinese community. But their success, I will argue, was based on certain secular activities rather than the religious message they sought to spread. One can conclude, therefore, that the Protestant missionary movement in twentieth-century China was most successful when it proved itself useful in secular ways.

This study began as an outgrowth of a public education program I helped organize a number of years ago on North Carolina s historic ties with China. I realized very quickly that significant untapped archival and human resources that would be valuable in examining Sino-American relations were near at hand. Furthermore, many of the participants were advanced in years and failing in health, so the task of preserving their memories and papers was urgent.

I came to concentrate on the Jiangyin mission station because several of its missionaries were still alive, because very detailed documentary records of the station were available in several archives and in private hands, because the stations work had educational and medical as well as evangelical dimensions, and because some possibility existed of examining the station’s history from a Chinese as well as an American perspective.

The Jiangyin mission station was maintained by the Southern Presbyterian Church (Presbyterian Church in the United States, or PCUS). Most studies of American missions in China have focused on northern denominations, using materials drawn from the files of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Southern Presbyterians have generally been neglected, but the denominations rich archival resources as well as personal and institutional resources specific to the Jiangyin Station afford a fairly comprehensive look into the life of that station and its involvement in the dramatic changes China was undergoing at the time of its operation.

The Southern Presbyterian Church broke away from its northern counterpart during the American Civil War to form a separate denomination with its own Board of Foreign Missions. In 1866, the PCUS board sent out its first missionaries to foreign lands, including one to China. The PCUS was one of the smallest of the mainline Protestant churches and one of the last to enter the overseas mission field, but it came to assume a leading role in foreign missions. In 1907, an interdenominational agreement assigned to the Southern Presbyterians responsibility for designated areas in several countries with a combined population of 25 million.2 Within a decade, among the nine major American Protestant churches, the Southern Presbyterians ranked first, on a per member basis, both in the number of missionaries sent abroad (about 9.5 per 10,000 members) and in the amount of support for foreign missions (about $1.50 per member).3 Most of the PCUS mission force and investment was in China, where it operated fourteen stations in the lower Yangzi province of Jiangsu. The PCUS divided its China field into two sections, the North Jiangsu Mission and the Mid-China Mission, separated by the Yangzi River. The Jiangyin Station was under the jurisdiction of the latter.

This study will focus on the mission station and its inhabitants, their attitudes, and their relations with the Chinese at certain critical points in modern Chinese history—the anti-Christian riots of the late 1890s, the fall of the empire in 1911, the warlord and revolutionary movements of the mid-1920s, the Japanese invasion of China throughout the 1930s, and the Communist triumph of the late 1940s. The missionaries were on the cutting edge of the penetration of American and Western institutions and values into China, and they consequently were among the first to experience the Chinese (and Japanese) reaction to that penetration.

An account of the Jiangyin Station leads to a consideration of many of the key issues concerning Chinese-American relations, such as Westerners’ role as a force for social reform and modernization, the corrosive effect of Christianity on Chinese life, the relationship between Christian missions and Western imperialism, the growth of Chinese anti-Christian and antiforeign sentiments, foreigners’ use and abuse of extraterritoriality privileges, the devolution of authority from Westerners to the Chinese in social institutions (churches, schools, and hospitals), and the impact of mission work in China on American attitudes and church organization.

How did the Jiangyin missionaries respond to the opportunities and challenges present in twentieth-century China? How was their Christian message received? What was the relationship between their religious and secular work? How did their work change in response to political and social upheavals? What role did they play in the lives of the communities that hosted them? What contribution did they make, along with missions elsewhere in China, to the modernization of that country? What, in the end, did they accomplish?

These questions may seem to be ethnocentric and mission-centric, and until recently, the search for the significance of missions in China has largely been a Western enterprise. But now the Chinese also have begun to consider seriously the nature of the Christian missionary movement in modern China. No longer are they content to dismiss the entire effort as simply a part of Western imperialist aggression. In the openness of the post-Mao era and with attention turned to economic and political development, Chinese scholars are trying to assess the contributions missionaries and Christianity made to the development of modern China.

The story told here is based mainly on missionary sources, including interviews with several of the Jiangyin missionaries, the missionaries’ personal papers, station reports published in missionary journals, private letters and the circular letters sent home by all Southern Presbyterian missionaries, and the archives of the denomination’s Board of Foreign Missions. But Chinese sources are not lacking. In the past decade, a series of articles published in the Chinese journal Jiangyin wenshi ziliao, some by Chinese who had been involved in the mission work, traced the history of the station and its institutions and evaluated its impact. Additional Chinese sources on the Jiangyin Station have been discovered, and they have been used to supplement the very full missionary record. It should be noted that missionaries were probably the most knowledgeable and perceptive foreigners in China. Most of them spoke Chinese well (usually the local dialect), and unlike foreign businessmen or government officials, missionaries were in constant contact with the Chinese in the small towns and villages, not just in the treaty ports. If handled carefully, missionary sources can provide a China researcher with a rich and intimate picture of the social and political conditions within the missionaries’ field of operations.

One valuable set of data was found at the First Presbyterian Church of Wilmington, North Carolina, with which the Jiangyin Station had a special relationship throughout its more than fifty years of existence. One of the station’s early pioneers, George Worth, was a Wilmington native and the grandson of a governor of the state. James Sprunt, an elder of the church and a prominent textile merchant, was the station’s main benefactor. The Woman’s Auxiliary of the church, in cooperation with other churches in the Wilmington Presbytery, tirelessly raised the funds needed to build and maintain the mission hospital at Jiangyin. The Wilmington church, in fact, became the first in the Southern Presbyterian denomination to assume responsibility for a specific mission field in China, the Jiangyin Station. The Jiangyin church was considered the “spiritual daughter” of the First Presbyterian Church. Matching the Wilmington church’s zeal in supporting the mission effort was its care in preserving all materials relating to that mission, including letters from missionaries recorded in the weekly bulletin and minutes of the Woman’s Auxiliary meetings.

The country about which Jiangyin missionaries wrote home and in which they were trying to effect a major ideological and cultural change was beset by enormous problems, many of them caused or exacerbated by the Western penetration of China since about 1800.4 Under the leadership of the British, Western traders were opening up China and seeking commercial and political advantages there. In their wake came secular and religious missionaries promoting Western values. Also around 1800, China’s internal difficulties mounted. Population growth began to outstrip the country’s ability to increase agricultural production. Added to this potentially explosive situation were administrative mismanagement and corruption. The Chinese government was now faced with the classic “internal disorder/foreign aggression” combination that had led to the downfall of earlier dynastic regimes. By the mid-nineteenth century, a series of crises confronted China.

Militarily, China suffered the first of many defeats at the hands of outsiders in the Opium War (1839–42), so-called because the British insistence on maintaining their very profitable trade in the drug precipitated a clash with the imperial government. The Taiping revolutionary movement erupted in the 1850s and for over a decade controlled a large part of south China, and smaller rebellions kept the government on edge for some time after that. In time, international incidents provoked other wars with Britain, France, Russia, and Japan. As a result, by the end of the century, foreigners had forced China to its knees and had gained enormous privileges codified in a series of “unequal treaties.” These included the right to reside in certain cities, the right to station troops there to protect foreigners’ lives and property, exemption from Chinese laws (extraterritoriality), control over the setting of duties on the importation of goods, and the right to propagate Christianity.

Intellectually, some Chinese leaders began to question the value of their traditional way of life and their cultural roots (generally referred to as “Confucian,” although other intellectual streams nourished them) and the ability of traditional methods to steer China safely through the storms of the modern world. Disillusioned intellectuals began looking for guidance to Western values that later came to be epitomized as “science and democracy” and to a variety of “isms,” such as liberalism, pragmatism, capitalism, individualism, socialism, and Marxism. This iconoclasm became stronger in the twentieth century, reaching an apogee in the New Culture and May Fourth movements of the late 1910s and early 1920s.

Politically, the Chinese (as an ethnic distinction) began to question the legitimacy of their government, some because it was headed by Manchus (who had conquered China and founded the Qing dynasty in 1644), and some because it was an authoritarian anachronism and yet, paradoxically, too weak by the late nineteenth century to defend China and provide effective rule. The strong political and economic development of neighboring Japan, a country the Chinese had long seen as subordinate to and influenced by China, only made matters worse and provided reformers and revolutionaries with a readily available model for change. The culmination of their efforts came in 1911 when the old imperial regime was overthrown and a newfangled form of government, a republic, was established, founded on “democratic” institutions.

The dawn of this new age, however, was not exactly rosy. Weak republican institutions gave way to militarists (“warlords”) who imposed their rule, or rather misrule, on China until they were swept away by revolutionary nationalism. Two revolutionary political organizations emerged in the 1920s: the Nationalist Party (Guomindang, or GMD) and the Chinese Communist Party (Gongchandang, usually referred to by its English acronym, CCP). These parties competed with each other—sometimes peacefully but for the most part through force of arms — for the next thirty years, each seeking to assume the mantle of nationalism, reunite the country, and restore Chinas rightful place in the world order as a powerful and respected nation. Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi) led the GMD to power in 1928, but he was never able to eliminate the CCP as a political and military threat.

Throughout this period, the foreign presence in China remained strong. Japan enlarged its presence and eventually engulfed China in another war from 1937 to 1945. Merging with the international conflict after Japans attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Sino-Japanese War devastated China’s economy and tore apart its social and political fabric. The postwar years quickly gave way to a renewal of the civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists. Finally, in 1949, the Communist forces overcame their rival. On 1 October, standing on the rostrum of the old imperial palace overlooking Tiananmen Square, Mao Zedong proudly proclaimed the birth of the Peoples Republic of China and announced that “the Chinese people have stood up” and removed the imperialist powers from their country. Included in the removal was the entire Christian mission force after nearly a century and a half of work.

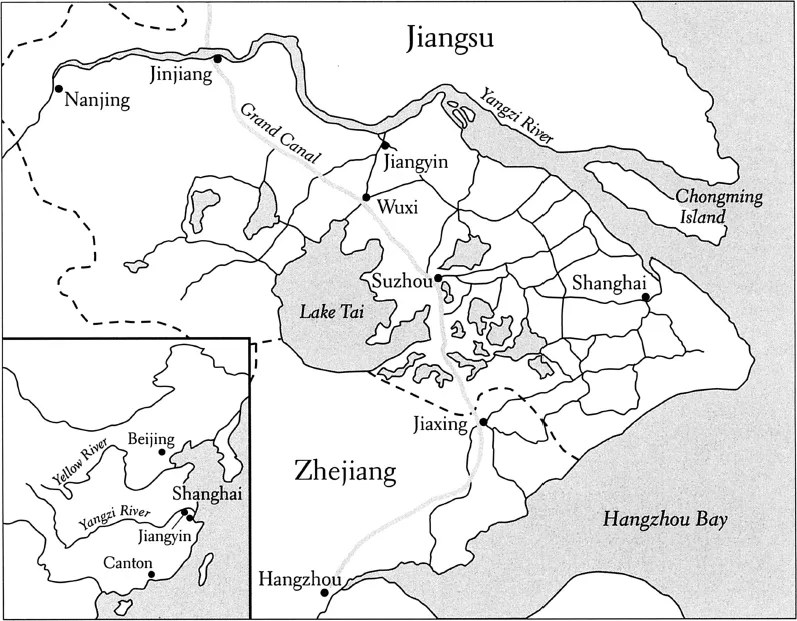

The geographical setting of our story is the city of Jiangyin on the south bank of the mighty Yangzi River, about 100 miles upriver from Shanghai. The two Chinese characters of the city’s name literally mean “river-shade,” referring to the city’s location on the “yin” side, which in China’s traditional yin/yang cosmology means the south or shady side, of the river. Arriving by steamer, passengers were transferred in mid-river to a ferry that took them to a north-side landing, where they then could hire a small boat to cross the river to reach the city. Traveling to Jiangyin became easier after 1926, when a landing was built on the south side of the Yangzi so passengers could alight directly from river steamers. The nearest city of any size was Wuxi to the south, which could be reached by boat along the canals that crisscrossed the area. Jiangyin was also the capital of the county (or district) of the same name. As such, it contained the government office (yamen) of the district magistrate (xianzhi), whom some foreigners referred to as “mayor.” In the early decades of the republic, the county had a population of about 600,000, distributed in about 50 small market towns and 5,000 villages. The city itself contained about 50,000 residents.

Jiangyin County, shaped roughly like a rectangle thirty miles long and fifteen miles wide, was a rich agricultural region, producing rice, soybeans, cotton, and silk. The level fields of the Jiangyin plain were surrounded by low mountain ranges that stretched south and east toward Shanghai. One of the missionaries, Virginia Lee, described an imaginary aerial view of the surroundings: “Could you be on the top of either eminence [Flower Mountain or Chicken Mountain], this plain would seem a patchwork of tiny fields of golden rice and emerald mulberry groves [for sericulture], embroidered with blue canals, beautiful to behold.”5 The canals may have been sparkling to the eye from a distance, but they posed constant problems. Fed by the Yangzi, they were often brown and thick with mud. The main canal to Wuxi had to be dredged about every ten years, and the smaller ones about every five years. When water rose quickly in the Yangzi, many canals became so swollen that some villages were inundated and houseboats could not pass under the bridges.6

Map 1-1. Jiangyin and the Yangzi Delta Region

Source: Based on map in John Fairbank et al., East Asia: Tradition and Transformation (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973), p. 481.

Since the tenth century, Jiangyin has been seen as a strategic point for the defense of the upper reaches of the Yangzi River from naval attack. Although it is some distance from the sea, some have called Jiangyin the “month of the Yangzi” because the river first narrows (to about one mile) at this point. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1643), the government strengthened the city walls and built ramparts along the river. In the 1640s, Ming loyalists in the city relied on these fortifications to launch a furious but ultimately futile resistance to the advancing Qing armies.7 The Qing government and ...