![]()

Chapter 1

Spiritual Gifts

Conversion as Cross-Cultural Practice

A delegation of Illinois Indians on a diplomatic mission astonished the residents of New Orleans in 1730 with their ardent participation in the Catholic ritual life of the colonial capital. The Jesuit missionary Mathurinle Petit observed that during their three-week stay “[the Illinois] charmed us by their piety, and by their edifying life. Every evening they recited the rosary … and every morning they heard me say Mass.” People crowded into the church to witness the spectacle of “savage” Indians worshiping and singing before the altar. The highlight for the audience was a responsive Gregorian chant in which Ursuline nuns “chanted the first Latin couplet … and the Illinois continued the other couplets in their language in the same tone.” The Illinois appeared to be very well educated in Catholic practice, pausing during their daily activities to recite a variety of prayers. “To listen to them,” concluded the priest, “you would easily perceive that they took more delight and pleasure in chanting these holy Canticles, than the generality of the Savages.” Le Petit was correct in a sense. The inhabitants of some of the Illinois villages had developed a strong attachment to Christianity through years of interaction and exchange with the French.1

Illinois leaders Chicagou and Mamantouensa arrived in the city at the head of the delegation to show solidarity with their French allies who were embroiled in deadly conflicts with Native nations in the lower Mississippi valley. In an audience with the French governor, Chicagou presented two calumets, or ceremonial pipes, one symbolizing the shared French-Illinois attachment to Christianity and the other the diplomatic and military alliance between them. The Illinois had since the middle of the seventeenth century engaged the French in calumet ceremonies to sustain friendly relations. In the 1690s, the Illinois converted in large numbers to Catholicism, adding a significant new dimension to the relationship. The connection now required two calumets, and one of these thoroughly Native ritual objects represented the religious traditions introduced by the French. This “Catholic” calumet seems an apt symbol for the ways in which the Illinois incorporated Catholicism into their lives. The calumet was an indigenous cultural vessel that now carried new meaning, just as the Catholic prayers the Illinois chanted in the New Orleans church in their own Native language contained Illinois cultural concepts.2

Indeed, the Illinois defined themselves as Christians through the ritual of prayer, through religious practice. Le Petit commented that “the Illinois … were almost all ‘of the prayer’ (that is, according to their manner of expression, that they are Christians).”3 The Illinois term was araminatchiki, for “those who pray.” Araminatchiki spoke, sang, and chanted Illinois words in a new Christian order and context, but these words could never be emptied entirely of their indigenous meaning. Ambiguity reigned in the volatile colonial world the Indians and French made together in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Effective navigation of this swiftly changing world required the kind of cultural creativity on vivid display in the houses of worship and colonial offices of New Orleans. The appearance of a “Catholic” calumet in 1730 represented the results of many decades of encounter and cultural translation, a particularly compelling example of the exchange of spiritual gifts.

A well-known early encounter between the Illinois and the French revealed the importance of these gifts in establishing and maintaining relationships. On 17 May 1673, the Jesuit Jacques Marquette embarked on his famous exploration of the Mississippi with the French trader Louis Jolliet and a small group of men. It took the travelers a month of hard work to make their way from the mission of Saint Ignace at Michilimackinac to Green Bay and, finally, into the mighty river itself. The party paddled down the Mississippi for a week without seeing any other people. Finally, on 25 June, they spotted a path leading inland from the water’s edge. Alone, Marquette and Jolliet followed the trail and approached a group of villages near a river. They shouted to announce their presence and waited for the villagers to greet them.

Marquette recounted that four old men walked slowly toward the two Frenchmen. Two of the men carried calumets, beautiful ceremonial pipes “finely ornamented and Adorned with various feathers.”4 Silently, they raised the pipes to the sun. Marquette was relieved to see the calumet ceremony because he knew the Indians reserved such treatment for friends and potential allies. He also noted that the men wore cloth, which indicated that they had traded in French goods. The men stopped before the explorers, and Marquette asked who they were. They replied that they were Illinois and then offered the calumets for the Frenchmen to smoke. The four Illinois men invited Marquette and Jolliet to enter the village, where the rest of the people waited impatiently to greet their foreign guests.

A long series of formal ceremonies followed. At the door of a cabin, an old man, entirely nude according to the missionary, extended his hands toward the sun and said, “How beautiful the sun is, O frenchman, when thou comest to visit us! All our village awaits thee, and thou shalt enter all our Cabins in peace.” Marquette and Jolliet entered the cabin, where a crowd of people watched them carefully. The priest heard some people say quietly, “How good it is, My brothers, that you should visit us.” The Frenchmen smoked the calumet again and then accepted an invitation from a “great Captain” to visit his nearby settlement for a council.5 Many curious Illinois who had never seen the French before lined the path to the village. The Illinois leader greeted them at his cabin flanked by two old men. All three were nude, and they held a calumet toward the sun. The two explorers smoked again and entered the cabin.

Marquette reciprocated, using four gifts to speak to the assembly. By the first, he informed the Illinois that the party explored the river and contacted its peoples with peaceful intentions. “By the second, I announced to them that God, who had Created them, had pity on Them, inasmuch as, after they had so long been ignorant of him, he wished to make himself Known to all the peoples; that I was Sent by him for that purpose; and that it was for Them to acknowledge and obey him.”6 The third present announced that the French monarch had subdued the Iroquois and would restore peace throughout the land. Finally, the fourth gift asked the Illinois to share their information about the river and the lands and peoples to the south.

The Illinois leader responded with a speech that welcomed the French explorers and requested that Marquette return to teach them about the great spirit. He then gave Marquette and Jolliet three gifts: a young Indian slave, an esteemed calumet, and a third unnamed gift that was part of a plea that the explorers go no farther. After the council, the hosts fed Marquette and Jolliet a ceremonial meal of four courses. The leader placed bites of boiled corn meal (sagamité), fish, and buffalo in their mouths as if the Frenchmen were children, but the visitors refused the dog that was offered as the third course. After the feast, an orator led them around the village to all the cabins, calling the people out to greet the visitors. Marquette explained that “every-where we were presented with Belts, garters, and other articles made of the hair of bears and cattle, dyed red, Yellow, and gray. These are all the rarities they possess. As they are of no great Value, we did not burden ourselves with Them.” The tired travelers slept in the captain’s cabin and the following day pushed their canoes back into the water in front of a crowd that Marquette estimated at almost 600 people. Pleased with their reception, the missionary promised to return the next year to instruct the Illinois, a people who had in his view “a gentle and tractable disposition.”7

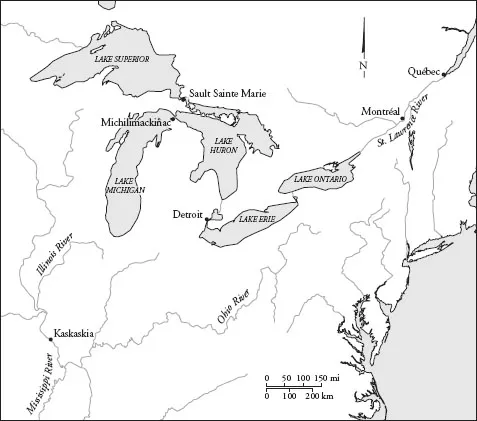

In this detailed journal, Marquette documented a voyage of exploration and discovery that marked the arrival of the French in the heart of the continent and the establishment of dynamic new relationships with Native peoples. The Jesuit superior in New France, Claude Dablon, applauded the success of the expedition. He noted the geographic significance of the river systems that Jolliet and Marquette traveled and declared the potential of the rich and beautiful lands that awaited colonization in the pays d’en haut, the upper country that lay above and to the west of the Saint Lawrence River valley. Dablon also viewed the waterways as key routes into a promising new field for evangelization. French officials responded quickly to the opportunity and by the early eighteenth century had created a colonial empire that stretched from the Saint Lawrence, through the Great Lakes, to the mouth of the Mis-sissippi. This grand empire was more fragile than it appeared on maps of European territorial claims, however. The French relied on the cooperation of Native peoples in sophisticated diplomatic alliances and elaborate commercial networks to maintain the interior colonies. Without cooperation, they were virtually powerless in a vast region that remained, in many ways, Indian country. Neither the French nor the diverse Native nations that lived in the region were able to impose their visions of stability on the region.8

The familiarity of Marquette’s account and the larger-scale concerns of French empire building all too easily obscure the complexity of what was really happening in the kind of close encounter the missionary described. There was an intimacy, intensely spiritual in nature, in the interaction. Not unexpectedly, Marquette framed the entire enterprise in religious terms. The missionary reflected in the first lines of his journal that when he received his orders to accompany Jolliet, “I found myself in the blessed necessity of exposing my life for the salvation of all these peoples.” The idea of death in service to God brought him joy. The planned journey seemed that much more auspicious in that the instructions arrived on the feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin, with whom he always claimed a special relationship. In the final section of the account, Marquette described the baptism of a dying child in a different Illinois village and concluded, “Had this voyage resulted in the salvation of even one soul, I would consider all my troubles well rewarded, and I have reason to presume that such is the case.” The baptism represented a moment of spiritual encounter that fit into the pattern already established through the ritual greetings, sharing of food, exchange of gifts, and problematic attempts at communication.9

Figure 1. Map of the pays d’en haut, or upper country

For the Illinois, too, the spiritual dimension of the encounter was important, although for very different reasons. In their case, unknown beings and strange events sometimes embodied or communicated manet8a, or “power” in the Illinois language, and therefore they required special attention and analysis. Reimagine for a moment the encounter from the Illinois perspective. It was midsummer, and the days were long, hot, and humid. The corn was well established in the fields so carefully tended by women. Someone heard shouting from the main path to the river, and two strangers appeared. What did these men want? Clearly, they were French, for the Illinois had seen and traded with them in the Great Lakes region to the north. Four elders went to greet the visitors, two of them carrying ap8aganaki, or calumets, which they raised to the sun as a sign of welcome and honor. The black-robed stranger asked who they were, a question difficult to understand because he did not speak well. “Inoki,” they replied, which meant “we are the people” in Illinois. The Frenchmen put the ap8aganaki to their lips, and the soothing smoke from the sacred herb drifted into the air, the first sign of a potential relationship. Together, the six men entered the village to continue the ceremonial greetings.10

“How good it is, My brothers, that you should visit us,” the people said. Two more times the visitors shared the ap8aganaki before they sat in the cabin of a prominent man to talk. The black-robed one offered gifts as he spoke; he seemed to know how to behave as a guest. He talked about peace and friendship and of spiritual things, too. He spoke with reverence about kichemanet8a, a great spirit, but the listeners could not discern the true nature of this being. When the man finished speaking, the Illinois leader presented a series of valuable gifts to show his respect and to signal his positive response to the offer of friendship and alliance. An Indian slave would accompany them down the river and the calumet would ensure a peaceful journey. Women delivered generous bowls of food to the cabin, and the host fed his visitors. They accepted most of the food in the carefully scripted ritual but refused the dog. Why? And why on the way out did they fail to take the intricately designed gifts offered by the people? Many things remained unclear, but the Illinois knew that these men, or others like them, would return. Hopefully, they would bring more gifts and items for trade. Maybe, with more men, they could help them fight their enemies in this tumultuous time. Perhaps the one who talked of manet8aki—spirits—had access to new rituals and valuable spiritual powers.11

Encounters like these initiated a complicated process of cultural translation and mutual conversion that lasted for a century in the pays d’en haut, the great expanse of land and water that encompassed the Great Lakes and Illinois country. Marquette understood that diplomatic protocol demanded that he present gifts to Indian leaders, but he probably did not fully appreciate the immense power in some of the gifts. If he had, the missionary likely would have gratefully accepted the finely crafted and vibrantly colored objects the Illinois pressed into his hands. It was precisely items like these that men carried into battle for protection and strength. A gift was not just a thing, a mute object. Gifts could speak, and some contained great power. Even the exchange of seemingly mundane items established potentially lasting relationships with mutual obligations.12

Although the value of these smaller gifts failed to translate clearly, Marquette easily recognized the calumet, ap8agana in Illinois, as a very special gift. As Marquette expressed it, the calumet “seems to be the God of peace and of war, the Arbiter of life and of death.” Marquette described the calumet: “It is fashioned from a red stone, polished like marble, and bored in such a manner that one end serves as a receptacle for the tobacco, while the other fits into the stem; this is a stick two feet long, as thick as an ordinary cane, and bored through the middle.” He continued, “It is ornamented with the heads and necks of various birds, whose plumage is very beautiful. To these they also add large feathers,—red, green, and other colors,—wherewith the whole is adorned.” Birds were powerful other-than-human beings, and their feathers possessed useful power. Dablon commented in his report on the expedition that “this gift has almost a religious meaning among these peoples.”

The spiritually potent pipes commanded great respect throughout the region and beyond, among many Native peoples. The Illinois used the calumet and its related ceremonies “to put an end to Their disputes, to strengthen their alliances, and to speak to Strangers,” as well as to demonstrate respect toward the manet8aki, the spirits who populated their world. The calumet communicated the sincerity and identity of its carrier. It served as a translator of peaceful intent. Marquette gladly accepted the priceless gift, and he later used it to avoid dangerous confrontations with wary Indians to the south. The exchange of gifts in the Illinois village represented the establishment of a respectful, reciprocal relationship with the two Frenchmen. They were no longer strangers. Participation in these rituals reflected a major adaptation to Native customs for Marquette and Jolliet, a kind of conversion. The Illinois had started to incorporate these men into an Indian world, even as the two visitors looked forward to a time when the French would rule a commercial empire populated by Christian Indians.13

Religious encounters in the pays d’en haut brought people together in ways that promoted exchange across cultural borders, but not in a simple or straightforward fashion. Colonialism and its effects—the appearance of colonial officials, traders, and missionaries; the movements of Native peoples responding to pressures and to opportunities; the establishment and desertion of villages, forts, trading posts, and missions; the impact of warfare, disease, and alcohol—created unsteady formations on which to build new relationships. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a confluence of diverse peoples in a complex colonial environment contributed to the social and cultural transformation of the upper Great Lakes and Mississippi valley.

It seems somehow appropriate that this transformation occurred in a place defined by its rivers and lakes, by swift currents and quiet coves, by rhythmic waves and sudden tempests. French missionaries paddled into this changing world to lead its transformation. On lakeshores and riverbanks, on long portage trails, and on high bluffs with golden prairie views, they tried to persuade Native people to accept them as teachers, ceremonial specialists, and political allies. In Indian lodges and wooden chapels, the missionaries urged their listeners to recognize the new manitous, the spirits that offered the only true path to paradise. The shared space of Native villages and Indian missions left ample room for a variety of responses. The priests delivered their message and conducted their rituals using Native languages. Cultural influences flowed in many directions, influencing the expression of missionary spirituality and the emergence (and the rejection) of Native Christianities. Ultimately, generations of encounter produced a series of colonial conversions, the creation of hybrid cultural forms and religious practices that reflected simultaneously the movement and the persistence of boundaries. These interactions gave birth to the “Catholic” calumet the Illinois presented to their French friends.

Singular definitions of conversion that depend on the idealized renovation of imperial subjects from “savages” to “Christians” are insufficient to explain the complicated processes that unfolded in this colonial world. The experiences of Native peoples and missionaries argue instead for the adoption of a plural, dynamic, and flexible concept of conversion that accounts for the changes in all participants. Such a perspective requires an analysis of religious action—orientation and movement, song and speech, ritual and relationships—more than it does a simple delineation of faith and doctrine. Ritual activity and social relations remained the basis for Native religious life even for those who adopted Christianity, the araminatchiki.14

The classic definition of conversion emphasizes the abandonment of indigenous religious practices for faith in a Christian God and “orthodox” Christ...