![]()

1

The Making of an Imperial Doctor

Also please do not change “England” to “Scotland”: the sense of the passage is that he left home too young to have made acquaintance with any big men at headquarters (which is London, not Scotland) who might have been a weight onto his feet afterwards and might have done for him what he [Manson] did for Ross. So it should be “England.” Scotland would be grotesque, since all Soctchmen come to England for their opportunity.

COLONEL A. ALCOCK TO P. H. MANSON-BAHR

8 October 1926, regarding their biography of Patrick Manson

Quinine is as valuable to a man shivering with ague as apiece of grey shirting; and when he knows this he will ask for it, and get it. But if grey shirtings were only to be got from one or two charitable individuals, either the mass would probably remain ignorant of their existence, or the charity of these individuals be soon exhausted. Private enterprise would be choked by the give-away-for-nothing system of the philanthropist, and certainly clothes for the millions would not be forthcoming. Left to the wholesome influence of supply and demand, we know how marvelous has been the result, and so it should be with quinine.

PATRICK MANSON

Medical and Surgical Report for the Amoy (China) Missionary Hospital for 1873

AT first sight, the village of Takow on the island of Taiwan (or Formosa, as it was then known) appears to be an unlikely place for Patrick Manson to have launched his career in medicine. Takow could not have been farther from his birthplace in Oldmeldrum, Aberdeenshire, or from his medical training at Aberdeen University in Scotland. But Manson’s career path was hardly an anomaly. It goes without saying that most graduates of English, Irish, and Scottish medical schools would have preferred to pursue lucrative careers as London consultants. Many tried, but few succeeded. This sobering reality did little to check demand for medical training after 1850. Most toiled away as providers in a competitive domestic medical market. Yet, as Britain’s formal territorial and informal commercial empire grew, an increasing number of practitioners pursued their careers abroad. Many sought the security of a salaried appointment in the state services, that is, the Army Medical Department, the Indian Medical Service, the Naval Medical Service, or the colonial medical services of the dependent empire. Others served on merchant and passenger vessels in hopes of a better situation. Still others preferred to gamble on the promise of cultivating markets for medicine in British colonies or in Britain’s spheres of influence. Regardless of their occupational status, as a group they practiced medicine as imperial physicians and, consequently, participated in the transformation of Victorian medicine into imperial medicine. As this chapter will show, Manson was both a product and an agent of this process.

The Making of a Doctor in Victorian Scotland

In a parish church in the farm town of Old Machar in northeast Scotland, Patrick Blaikie, a retired Royal Navy surgeon, gave his eighteen-year-old daughter Elizabeth away in marriage on 16 June 1842.1 The groom was John Manson, a thirty-five-year-old property owner and bank agent for the North of Scotland Banking Company in Oldmeldrum, a prosperous farm town in the county of Aberdeenshire.2 Shortly after their marriage, John and Elizabeth moved to a large four-bedroom house with surrounding farmland on Cromlet Hill in Oldmeldrum. The Manson family quickly outgrew their home. First came John Blaikie in June 1843. Patrick followed him in October 1844. Forbes was born in March 1846, David in July 1847, Margaret Knight in November 1848, Alexander Livingstone in July 1850, Elisabeth Livingstone in August 1852, Helen in May 1854, and Alice in January 1856.3

In 1859, John and Elizabeth relocated the family to 22 King Street in the eastern portion of Aberdeen. Their decision to migrate to the city, some twenty miles from Oldmeldrum, conformed to a well-established pattern of internal migration in northeastern Scotland. As the regional center of banking, higher education, insurance, and law, Aberdeen was the magnet for the growing population in the hinterland of the county. Between 1801 and 1851, Aberdeen’s population nearly tripled, from 26,900 to 72,000.4

In moving, John and Elizabeth gave up the rural gentility of Cromlet Hill for a plain townhouse in a middle-class district of the city. The loss in charm was more than made up for in space. The twelve rooms comfortably accommodated a household consisting of two adults and eight growing children. Three female servants lightened the work for Elizabeth. If the number of servants is taken as an index of social class, King Street included a wide spectrum of the middle class. Next-door to the Mansons lived a grocer and his wife, who employed one servant. At 36 King Street, George Morrison, a doctor, and his wife shared their one servant with a traveling-salesman lodger. Farther down the block, customs collector Daniel Briston and his wife and two sons looked after themselves.5

Like other families of the burgeoning Aberdeen middle class, John and Elizabeth regarded a university education as the best means of securing their sons’ social advancement. (The eldest son, John, apparently died young, as virtually nothing is known about him.) This concern accounts for their decision to enroll Patrick, David, and Forbes in West End Academy, New Town Grammar School, and the Gymnasium, respectively.6 Unlike locally supported burgh schools, which concentrated on commercial subjects, these proprietary schools were geared to prepare their students for the entrance examination of the recently reconstituted University of Aberdeen.7

In preparing Patrick for this examination, John and Elizabeth had already determined what career he was to pursue. A medical degree offered the best value for achieving financial independence and social advancement. Although Scotland’s universities as well as its medical corporations produced far more doctors than could be assimilated in the small medical market, many found employment by migrating south to England. The reciprocity provision of the 1858 Medical Act, which placed Scottish medical degrees and qualifications on the same footing as those from England, probably made migration all the more attractive.8 For those graduates without prospects in either Scotland or England, there was always the vast British empire. The demand for medical personnel continued, whether in the various state and colonial medical services or for private practitioners in the growing colonies of white settlement in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa.

Manson’s success as a medical student at Aberdeen University showed the wisdom of his parents’ decision. After passing the preliminary examination in 1861, he attended lectures and demonstrations on anatomy, botany, chemistry, clinical medicine and surgery, materia medica, medical jurisprudence, and midwifery. Between April and July 1862, Manson obtained his pharmacological experience; he completed his surgical and medical apprenticeship at the Royal Infirmary at Aberdeen and Edinburgh the following spring and summer.9 His two professional examinations, in 1863 and 1864, were each recognized as “deserving of commendation.”10 In 1865, he received his baccalaureate degree in medicine with honorable distinction. He then collected material for his master’s thesis while working as an assistant medical officer at a lunatic asylum in Durham County at Winterton.11 After he submitted his thesis, entitled “On a Peculiar Affection of the Internal Carotid Artery in Connection with Diseases of the Brain,” the university conferred Manson’s medical degree in 1866.12

Excellence at medical school did not translate into career success either in Aberdeen or in England. It is likely that even before Manson received his medical degree, he had decided that a career in Britain was beyond his reach. Manson passed his third medical examination three months shy of his twentieth birthday; twenty was the minimum age for practicing legally (Figure 2). During this period, he visited his uncle in London, where he read and visited hospitals and museums.13 To be sure, being at the center of the medical profession in England was an exciting experience for a young man living away from parents and siblings for the first time. But it was also a sobering look at his future career.

Launching a career in London was not easy, nor was success guaranteed. As Jeanne Peterson and Anne Digby have shown, the fee-for-service medical market was highly competitive. The bulk of the population relied either on home remedies or on those purchased over the counter at the chemist’s. Private practitioners faced competition from new institutions, such as voluntary hospitals and cash-dispensaries, which emerged in the nineteenth century to deliver health care to the laboring and lower middle classes. While these hospitals played a vital role as sites for medical and surgical training and innovation, they shrank the size of the fee-paying market. Unlike voluntary hospitals, cash-dispensaries democratized health care by offering low-cost medicine at a fixed charge. But retailing medicine, based on economies of scale, diminished the ability of other practitioners to maximize the value of their services. For the comparatively few practitioners who serviced a middle- and upper-class clientele, competition was equally intense. While social connections and economic resources enabled them to buy into and cultivate a practice, the sheer abundance of doctors made retaining and recruiting new clients an ongoing and uncertain process.14

2. Patrick Manson in 1864. From Philip H. Manson-Bahr and A. Alcock, The Life and Work of Sir Patrick Manson (London: Cassell, 1927).

Besides a highly competitive medical market, Manson faced another obstacle, namely, metropolitan discrimination against Scottish professional qualifications. In spite of the reciprocity provision of the Medical Act of 1858, candidates for the leading London hospitals and public posts were expected to possess a qualification from the Royal College of Surgeons or the Royal College of Physicians.15 This expectation had little to do with the quality of training in Scotland; rather, it reflected the institutional power of the Royal Colleges. By the second half of the century, College men dominated the senior hospital ranks and, in turn, made membership in the Colleges virtually obligatory for those seeking hospital positions and public posts.16 For graduates of Scottish medical schools, the power of the Colleges not only unfairly questioned the integrity of their medical training but also increased the costs of pursuing a career in London.17 Some looked for less prestigious posts either in the metropole or in the provinces. Still others saw their opportunities outside of Britain altogether. In 1866, Manson secured an appointment as a port surgeon in the Imperial Maritime Customs Service.

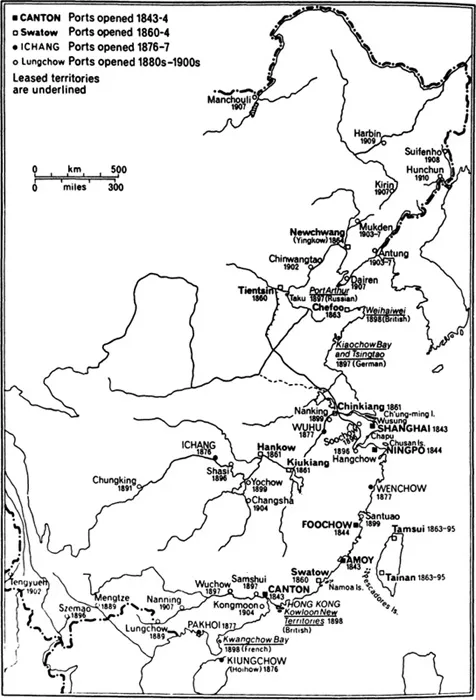

The Imperial Chinese Maritime Customs Service was not a part of the formal British empire per se. As the name implies, the service, which collected duties and maintained the shipping facilities in designated ports, fell under the authority of the emperor of China. In truth, the customs service gave expression to the ascendancy of Britain and the Western powers after China’s defeat in the Opium Wars (1838-42 and 1856-58). These wars grew out of China’s attempt to curb the importation of illicit Indian-grown opium. Britain used its leverage after these wars not to rule China as a colony but to secure the Chinese imperial state’s sanction for a wider field of Western trade in designated ports by treaty (see map).18 As a product of gunboat diplomacy, the customs service supplanted a highly regulated indigenous system of trade whereby Western merchants had been confined to Canton and dependent on native intermediaries. Led by Inspector-General Robert Hart, an Anglo-Irishman, the service facilitated East-West trade and served as an influential conduit of Western science and technology in China well into the twentieth century.

When looking back on the start of his career, Manson recalled that he had sought an appointment as a port surgeon in the Imperial Chinese Maritime Customs Service because of his “adventurous spirit.”19 It is more likely that when Manson surveyed his career prospects, occupational emigration appeared to be a risk worth taking: He did not seek a metropolitan corporate qualification. For a medical graduate eager to translate his training into financial independence, a customs appointment possessed several advantages. Unlike those seeking entry into the Army Medical Department, the Indian Medical Service, and the Naval Medical Service, whose requirements included passing a competitive examination and completing a mandatory course of instruction, port surgeons were expected to have only medical and surgical qualifications.

Growth of treaty ports. From Denis Twitchett and John K. Fairbank, The Cambridge History of China, vol. 10, Late Ch’ing, 1800-1911, pt. 1, p. 512.

The financial prospects were also encouraging. As the unofficial medical personnel of the treaty ports, customs officers mainly certified the health of arriving merchant seamen and departing emigrants. The fees, which were paid by shipowners and emigrants, could be considerable at busy ports. Beyond these fees, China offered unique conditions for an enterprising practitioner to build a prosperous private practice. Apart from missionary doctors, port surgeons had the advantage of being among the only Western doctors in treaty ports. The health-care needs of the foreign settlement communities as well as the merchant seamen provided a ready, if not captive, clientele. Finally, as liminal spaces between the East and the West, treaty ports offered a potentially vast market for Western medicine in the local Chinese population.20

Manson’s decision to seek his fortunes outside of Britain was not unusual for an Aberdeen graduate. Ten out of nineteen h...