![]()

1

Learning to Drive

FROM THE VERY INTRODUCTION of the car into American lives, instructions for how to drive evolved in a gendered manner. The physical demands of early cars, combined with an early, entrenched belief that only men should drive, set the stage. Although secondary schools, organizations, and corporations sought to educate teenagers on driving, they remained convinced that young men were the real drivers. This expectation undoubtedly contributed to the relatively smaller percentage of younger women who drove and the later need to target women for instruction as older adults. The tensions over who should teach women to drive and how to teach them revealed a consistent expectation that men had natural driving ability and women did not.

Driver’s licensing, while a more uniform process, also created different outcomes for women and men, as issues of marital status and the significance of appearance weighed differently on them. Instead of acquiring a key to freedom, women found their weight, age, and appearance documented and exposed for all to judge. Indeed, their very identity, their name, remained something to be contested with each application and renewal, and potentially varied with each change to their marital status.

Many critics used humor to disparage the driving skills of novice female drivers. As early as the 1930s, a strong cultural response suggested that women who could not drive were shrews who chose instead to critique men’s driving. The stereotype of women as “backseat” drivers empowered men to mute women’s guidance and feedback.

“I’m a Typical Teenage Girl”

The question of whether women should learn to drive began simultaneously with the introduction of motor vehicles. An early publication, The Horseless Age, sought to answer the question in 1898, assuring readers of the ease in driving the new “motor carriage.” The author recounted a story of a young woman who had seen but never ridden in a car. After about an hour of riding, she took her place behind the wheel and quickly learned to drive. Challenging a belief that drivers needed “skill and long experience” to operate this new machinery, the author hoped readers would recognize women as able drivers and the automobile as readily accessible to all who tried it.1

According to an article in the Woman’s Home Companion in 1900, “Several manufacturers have opened academies where instruction is given in the operation of the motor carriages.” While society remained conflicted about the notion of women drivers, manufacturers had a stake in encouraging women to learn to drive. Acknowledging that only a few motorists existed in America’s large cities, the article nonetheless promoted the automobile’s qualities and established women’s aptitude for it.2

Women, though, continued to make up only a small percentage of drivers, and the number of driving instructors remained miniscule. A 1914 New York Times article featured one female instructor who claimed that the number of women remained small because driving challenged their gender identity. She noted that initially women were thought to be “too frail to drive a ‘devil wagon,’ ” and that those who did “were looked upon as being mannish” as they cranked a car to start it, manipulated the steering apparatus, and shifted gears.3 She believed that the key to increasing the number of women behind the wheel would come in women’s growing confidence as they drove and cared for a car.

Rural farm women used the car as an important tool to aid their housewifery, bringing goods to market. They also used the car to seek out social opportunities to sew and cook with other women, including family and friends. Women also sought urban fashion and used cars to acquire new styles. One 1930 study of Midwestern farm families, for example, discovered that women made about “two-thirds of all clothing purchases out of their country environs.” That did not mean, however, that girls and women necessarily had licenses to drive. Historian Mary Neth found that girls were the “least likely to know how to drive” and discovered one study that revealed “that while 81 percent of country boys in Missouri drove cars, only 46 percent of the rural girls did.”4

Instilling that confidence increasingly fell to organizations and schools offering driving instruction. Although most targeted both sexes, they occasionally singled women out. Motivated by the exigencies of war, many private organizations offered driving lessons in the buildup to America’s entry into World War I and during the war. Thereafter, the urgency fell off and did not pick up again for about a decade. The American Automobile Association (AAA), for example, recorded praise for its first “women drivers” course offered in Washington, D.C., in 1929. The local assistant superintendent of police thought the AAA course would improve public safety but also wondered, “Why confine this instruction course to women drivers only as I am sure we have some male drivers who would find that an instruction course of this nature would materially help their driving.” While occasionally someone made such an observation, frequently assumptions about women’s inabilities coexisted with blind faith in men’s ability to drive.5

In the 1930s, Americans embraced driver’s education for young adults in the nation’s secondary schools. There continued to be stand-alone programs for adults, like the St. Louis Women’s Safe Drivers’ School, but for the most part instructional efforts centered on teenagers. Enrolling students as young as fourteen, these elective school programs maintained that instruction was a critical part of the country’s growing automotive safety imperative. Even before they could drive, girls and boys were taught about the car and the driving laws. The schools joined forces with the automobile and insurance industries to teach young people with replica automobiles that featured driving simulators.6

Before they could teach young people how to drive, however, schools needed trained instructors. This initially proved problematic, with only a few colleges and institutes offering training. Moreover, safety fears pervaded accounts of the instruction, with one of the pioneers of driver’s education, Amos Neyhart, remarking in 1937 that past instruction had only enabled people to “drive after a fashion.” By joining forces with AAA, he sought to exceed the minimal state expectations and truly empower drivers to “manage and control today’s fast-moving automobiles” to lower the number of fatalities on the road. Even with the growing feminization of the teaching profession, few women appeared in the front of driver’s education classrooms.7

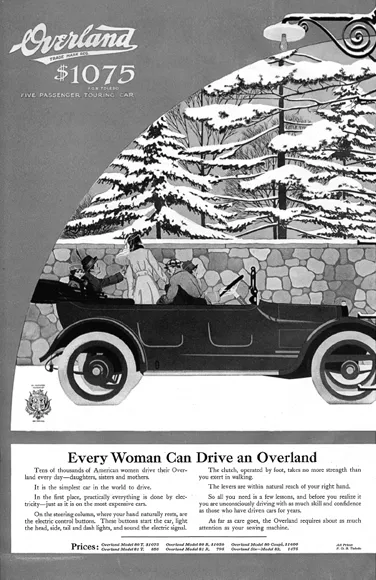

FIGURE 3. This 1915 Overland ad featured a woman at the wheel, with men in both the passenger seat and the backseat. The text assured women that its care required “about as much attention as your sewing machine.”

In addition to saving lives, individuals, organizations, and corporations also saw the potential for sales in instruction manuals and advertising their products. Although occasionally they were even targeted to young children, most efforts centered on teens. General Motors, for example, issued its first printing of We Drivers in 1936, and updated it through the 1960s. Companies undoubtedly hoped high school or college driver’s education classes would adopt their guidebooks and build brand loyalty for their cars and services. The AAA’s Sportsmanlike Driving, for example, was first printed in 1936 and continually updated through the late 1980s. It centered on the social and emotional issues drivers must consider, including “The Psychology of the Driver” and “Courtesy.” While most twenty-first-century Americans likely consider “road rage” a modern problem, concern with “overgrown babies” at the wheel appeared in early guidebooks as well. The books generally did not offer written gendered guidance, although the driver imagery was decidedly male. A 1955 Sportsmanlike Driving text made references to men as “the unpopular show-off” and “baby blow-horn.”8

Although ubiquitous in American culture and required in about half its states, driver’s education has never been nationally mandatory and many studies revealed its ineffectiveness in decreasing the number of automobile accidents for young people. As one 2008 government report concluded, “Teens do not get into crashes because they are uninformed about the basic rules of the road or safe driving practices; rather, studies show they are involved in crashes as a result of inexperience and risk-taking.” Indeed, some studies even found that those who took the classes had a higher rate of accidents than those who did not. Most states recognized that the primary reason for those accidents stemmed from putting young people on the road and embraced graduated license programs that limited when and how teens could drive at ages sixteen and seventeen. Still, in spite of its limitations, driver’s education remained a part of the process of learning to drive a car. Insurance and automotive companies, therefore, continued to seek opportunities to put their products in the hands of the millions of new drivers, especially teenagers without established brand loyalties.9

Popular driver’s education portrayals generally spared girls and women no criticism in their depictions of poor drivers. In a 1969 television commercial, American Motors touted that professional driving schools used more of their cars than any other manufacturers’ cars and, to demonstrate their durability, the ad showcased six bad drivers. While the featured men drove jerkily, panicked, and hit a fire hydrant, the portrayals of the three women were much worse. The first ground the gears, trying to find first, and then could not stay on the road; another was told to turn left and claimed she could not with the instructor watching, and then turned too soon over the traffic island; and the last one, when told to look out for the truck and bus replied in a high-pitched voice, “What truck? What bus?” as she wove dangerously through oncoming traffic. The company portrayed the men as novices and the women as incompetents.10

This condemnation of women’s driving continued into the twenty-first century, with a 2010 Allstate Insurance commercial that featured a spokesman acting as though he were a teenage girl. It opened with him in a pink, oversized sport utility vehicle (SUV) in a parking lot. His pink sunglasses and the script conveyed his “girl” identity. In the thirty-second spot, he drove carelessly, holding his cell phone, and telling the viewer, “I’m a teenage girl. My BFF Becky texts and says she’s kissed Johnny. Well that’s a problem cause, I like Johnny. Now, I’m emotionally compromised.” He then threw the cell phone into the back and slammed the SUV into another car’s front fender. He then concluded of his “Mayhem,” “Whoopsies. I’m all ‘OMG, Becky’s not even hot.’ ” After suggesting that teenage girls are reckless, bad drivers, he warned motorists that they unknowingly share the road with these terrible drivers and had best get Allstate insurance. The fifteen-second spot was even less subtle. It opened with him announcing, “I’m a typical teenage girl,” getting a text message on the phone, slamming the SUV into a car’s fender, and driving off. According to Allstate, it was typical of teenage girls to text and drive, as well as to crash into other cars because they were emotionally unstable. Other ads included poor behavior by teenage boys and men. Female behavior, however, was singled out as “typical teenage girl” behavior, while that of males was more individualized. Advertisements and the broader culture consistently portrayed women, and girls in particular, as poor drivers.11

“Drive with Both Hands if You Expect to Live and Marry Her”

Female passengers admonished individual young men not to endanger young women with their driving. An early cartoon chastised men, “Drive with both hands if you expect to live and marry her.” Companies commonly premised ads promoting driving safely on women’s preference for safety and young men’s recklessness. Placed only in periodicals targeting boys, such as Boys’ Life and Hot Rod, with no comparable ads appearing in Seventeen, the ads used shame, humor, and adult mentors to send the message to boys that driving dangerously could leave you without a date, a license, or your life or someone else’s. Headlined “That’s the Last Time I Ride with That Show-off,” one 1939 ad for Ford had a girl resolving never to go out with a “cut-up” whom she deemed an “infant,” who “doesn’t know enough about driving to put out his hand at a turn.” A 1960 General Motors ad maintained, “The cars are safer . . . the roads are safer . . . the rest is up to YOU!” and targeted boys in their role as both driver and protector. Beneath the photograph of a girl and boy headed off in the car to go ice-skating, the text recounted their conversation, “ ‘Don’t worry, Mom, we’ll be careful.’ She says that as you’re walking her out to the car. And what a responsibility this means for you, the driver! Her folks, your folks, the parents of everyone riding with you depend on your safe driving ability and mature judgment.”12

The rhetoric about bad male drivers centered principally on individual men and their immature behaviors. Men’s deadly actions did not indict the male sex, but they supposedly reflected a limited number of exceptions to the sacrosanct expectation that men were the better drivers.13

Starting in the 1950s, driver’s education classes relied on films to communicate their safety messages and tried to scare young people straight. The stories centered on traditional gender roles with a reckless male driver and a victimized female passenger. These movies grew increasingly terrifying, and eventually used actual graphic footage shot by police officers arriving on the scene of accidents to emphasize that young men, particularly in cars with souped-up engines, needed to drive more carefully and considerately. The narration of the movies underscored the carnage. The male narrator of Mechanized Death warned, “These are the sounds of excruciating agony. . . . This is not a dream, not a nightmare. This is real.” The opening of The Last Prom asked, “Was it a pretty face that made this gaping jagged hole in the windshield?” The films used girls’ facial scars to drive home that a poor decision by male drivers would end a girl’s life, if not literally, figuratively. Last Date had the girl who survived a boy’s deadly crash narrate the movie with her back to the camera because the accident left her face so disfigured that she would not show it. The movies suggested that a girl who lost her beauty in a car crash suffered a social death, so women had a vested interest in controlling male behavior behind the wheel.14

According to New York University’s director of the Center for Safety Education in 1960, “The major accomplishment in the field of driver education may be described as moral. The willingness of the schools to include this instruction implies a feeling of moral responsibility for the preservation of lives from death and injury.” Trying to reach young people’s impressionable minds and emphasize ethical concerns about taking the wheel, instructors wanted to temper young people’s egos by reminding them of the obligations of citizenship. They did so primarily by assuming that the driver was always male and the passenger and potential victim was female.15

In 1971, the AAA magazine American Motorist highlighted the success of Cissie Gieda in becoming the president of the American Driver and Traffic Safety Education Association. While recounting some of her successful te...