![]()

CHAPTER 1

“The Insurrection of the Blacks in St. Domingo”: Remembering Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian revolution cast a long, dark shadow over the Atlantic world long after its conclusion. Europeans, Africans, and Americans remembered the extraordinary upheaval in conversations in homes, taverns, and shops, on rural plantations, city streets, and ocean-going vessels. They remembered it in newspapers and pamphlets, portraits, engravings, histories, biographies, and fiction, which writers published, sellers traded, and consumers shared on both sides of the Atlantic. These memories were both numerous and contradictory. They were, like the revolution itself, fiercely contested. The result was the emergence of two competing narratives that promised to tell the true story of the events that took place in Haiti.

There was first the horrific Haitian Revolution. It told of vengeful African slaves committing unspeakable acts of violence against innocent and defenseless white men, women, and children. Among its most influential architects was Bryan Edwards, the Jamaican slaveowner and author who first published his widely read account of the revolution, An Historical Survey of the French Colony in the Island of St. Domingo, in 1794. The proslavery polemic catalogued the “horrors of St. Domingo” at great length: “Upwards of one hundred thousand savage people, habituated to the barbarities of Africa, avail themselves of the silence and obscurity of the night, and fall on the peaceful and unsuspicious planter, like so many famished tigers thirsting for human blood. Revolt, conflagration, and massacre, everywhere mark their progress; and death, in all its horrors, or cruelties and outrages, compared to which immediate death is mercy, await alike the old and the young, the matron, the virgin, and the helpless infant.” There was no precedent for what took place in Haiti. “All the shocking and shameful enormities, with which the fierce and unbridled passions of savage man have ever conducted a war, prevailed uncontrolled. The rage of fire consumes what the sword is unable to destroy, and, in a few dismal hours, the most fertile and beautiful plains in the world are converted into one vast field of carnage;—a wilderness of desolation!” Though Edwards wrote for a British audience, he provided the text for images of the revolution that would haunt generations of American slaveowners.1

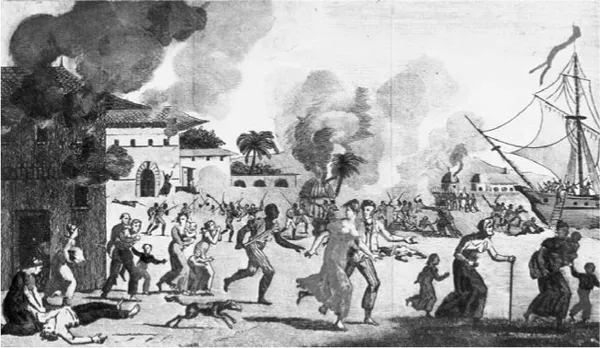

Figure 2. This early rendering of “The Burning of Le Cap,” tries to capture the horror of slave revolt. The caption reads, “General Revolt of the Negroes. The massacre of the whites.” Saint-Domingue, ou Histoire de Ses Révolutions. ca. 1815 (Paris: Chez Tiger, 1815). Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Second, there was the heroic Haitian Revolution. It was the story of an enslaved people who under the leadership of an extraordinary black man, a Great Man, vanquished their violent oppressors in an effort to secure both liberty and equality. This narrative was epitomized in the histories of Marcus Rainsford, which the British army captain printed multiple times in book and periodical form beginning in 1802. The soldier and author wrote that, while some acknowledged the “talents and virtues” of the African race, “it remained for the close of the eighteenth century to realize the scene, from a state of abject degeneracy:—to exhibit, a horde of negroes emancipating themselves from the vilest slavery, and at once filling the relations of society, enacting laws, and commanding armies, in the colonies of Europe.” Rainsford anticipated “the wonderful revolution” that produced the second independent nation in the Americas would “powerfully affect the condition of the human race.” Rainsford had met Louverture personally and venerated him. He considered him a “truly great man,” whose character and principles, “when becoming an actor in the revolution of his country, were as pure and legitimate, as those which actuated the great founders of liberty in any former age of clime.”2

These conflicting versions of the same event are difficult to reconcile. As anyone studying the Haitian Revolution is aware, the line separating fact from fiction is often indistinguishable. This is something that did not escape the contemporaries of Edwards and Rainsford. One critic writing from London abandoned his quest for the truth after negotiating some of the early print culture on the revolution, asserting, “The cruelties said to be daily perpetrated by the French and the Blacks of this island are, for the most part, fabricated.” Writers were “very prodigal in their use of fire and sword, hanging and drowning.” They would “occasionally, to furnish out a gloomy paper, massacre an army, or scalp a province.” There was consequently no reason to “believe one half of the cruelties which are reported.”3 An American who shared these suspicions warned readers, “The late intelligence from the West-Indies rests principally on verbal accounts, and on rumor, which frequently is the echo of falsehood and always of exaggeration:—It must therefore be received with distrust, and credited with caution.”4

We will never know the real history of the Haitian Revolution. There is no way to prove Edwards’s claims based on hearsay evidence that rebel slaves committed such grisly acts as sewing the severed heads of white planters into the bellies of their pregnant wives. Nor is there evidence to confirm Rainsford’s assertion that he provided the only true and authentic account of Louverture and the “black republic” in spite of the fact that he owed his life to the general, who saved him from the gallows.5 What concerns us here is that as a symbol of both the horror and the heroism of slave rebellion, the Haitian Revolution resonated in both American and Atlantic public culture throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

While the real story of what took place in Haiti between 1791 and 1804 is enigmatic, among historians one thing is axiomatic: the horrific narrative of the Haitian Revolution triumphed in early American memory. White southerners’ fears of slave insurrection among an exploding black population explain why this is the case. These fears, which according to David Brion Davis were “like a weapon of mass destruction in the minds of slaveholders,” are well documented.6 One need take only a cursory glance at Herbert Aptheker’s American Negro Slave Revolts to glimpse into white southerners’ panicked and paranoid world.7 In the equally groundbreaking White over Black, Winthrop Jordan writes that the specter of slave rebellion presented “an appalling world turned upside down, a crazy nonsense world of black over white, an anti-community which was the direct negation of the community as white men knew it.”8 It was because of this constant fear of having their world overturned that American slaveowners seized on the Haitian Revolution as a symbol of the horrors of a multiracial society without bondage.

The response to what many acknowledge as the bloodiest slave revolt in the history of the United States provides an example. In August 1831, Nat Turner, a plantation laborer and mystic, spurred dozens of bondmen to murder nearly sixty white men, women, and children under the cover of darkness in Southampton County, Virginia. Armed white bands apprehended Turner and his accomplices, and in their zeal to exact vengeance murdered countless African Americans who had no connection to Turner or his revolt. White officials eventually tried and executed Turner, leaving his body mutilated and dismembered.9 The rebellion shocked the nation, leading to public debate over the future of slavery. While the Virginia legislature debated a plan of gradual emancipation, Assemblyman Thomas Jefferson Randolph warned, “The hour of the eradication of the evil is advancing, it must come. Whether it is affected by the energy of our minds or by the bloody scenes of Southampton and San Domingo is a tale for future history.”10 As the remark by Thomas Jefferson’s grandson and namesake attests, memory of the Haitian Revolution infused the public response to the revolt.

Although there is no definitive link between Turner’s revolt and the Haitian Revolution, and Turner made no mention of it in interviews conducted in the days leading up to his execution, one man insisted on the connection in a pamphlet published in the immediate aftermath of the revolt. Samuel Warner opened his sensational account of the insurrection with the titular exclamation “HORRID MASSACRE” and then began:

In consequence of the alarming increase of the Black population at the South, fears have long been entertained, that it might one day be the unhappy lot of the whites, in that section, to witness scenes similar to those which but a few years since, nearly depopulated the once flourishing island of St. Domingo of its white inhabitants—but, these fears have never been realized even in a small degree, until the fatal morning of the 22d of August last, when it fell to the lot of the inhabitants of a thinly settled township of Southampton county (Virginia) to witness a scene horrid in the extreme!—when FIFTY FIVE innocent persons (mostly women and children) fell victims to the most inhuman barbarity.11

Though the veracity of Warner’s “Authentic and Impartial Narrative” is doubtful, he nevertheless claimed to have gathered information from face-to-face conversations with Turner’s accomplices.12 In these exchanges, they recorded that Turner spoke to them of “the happy effects which had attended the united efforts of their brethren in St. Domingo, and elsewhere, and encouraged them with the assurance that a similar effort on their part, could not fail to produce a similar effect.” Like Haitian slaves, Turner “was for the total extermination of the whites, without regard to age or sex!” He promised “That by so doing, they should soon be able (in imitation of the example set them by their brethren at St. Domingo) to establish a government of their own.” Warner concluded with a brief narrative of the revolution and a comment on the likelihood of its repetition in the United States: “Such were the horrors that attended the insurrection of the Blacks in St. Domingo; and similar scenes of bloodshed and murder might our brethren at the South expect to witness, were the disaffected Slaves of that section of the country but once to gain the ascendancy.”13

A letter forwarded to the governor of Virginia from a man claiming to be a runaway slave offers additional evidence of the depth of the shadow the Haitian Revolution cast over the South in the aftermath of the Turner revolt. The author, who signed the letter “Nero,” warned of a revolutionary conspiracy to destroy slavery in the United States. Nero described the formation of an abolitionist army under the direction of a Louverture-like figure who after escaping from slavery in the United States had fled to Haiti, where he joined a group that took “lessons from the venerable survivors of the Haytian Revolution.” Describing the intentions of this “Chief” and his fellow insurgents, Nero taunted the Virginia governor: “They will know how to use the knife, bludgeon, and the torch with effect—may the genius of Toussaint stimulate them to unremitting exertion. It is not my intention to boast, nor to threaten beyond a certainty of performing. We have no expectation of conquering the whites of the South States—our object is to seek revenge for indignities and abuses received—and to sell our live[s] at as high a price as possible.” The letter is revealing on a number of levels. First, while evidence suggests that Turner only needed to swallow the bitter pill of slavery to inspire him to sacrifice his life for freedom, his allies understood his actions in the framework of the transatlantic struggle for black freedom begun in Haiti four decades earlier. Second, apocryphal though the letter may be, it reinforced the widespread belief in the likelihood of a second Haitian Revolution in the antebellum South.14

The reaction to the Turner revolt demonstrates how, throughout the antebellum period, public memory of the Haitian Revolution endured through oral and printed accounts of southern slave revolts and conspiracies. These accounts served as “lieux de mémoires” or “metaphoric sites of collective memory,” which recurrently implanted the revolution into American memory.15 Conversations among participants, witnesses, and writers before, during, and after both real and imagined slave revolts activated collective remembering of the Haitian Revolution. The examples are numerous. Following the failed attempt of an enslaved blacksmith named Gabriel to launch a slave insurrection in Richmond, Virginia, in 1800, speakers and writers drew comparisons between local events and those taking place simultaneously in Saint-Domingue. Slave testimony added fuel to the conspiratorial fire, as bondmen revealed that Gabriel’s army not only included a number of French immigrants, but planned to spare the lives of the members of several trusted groups, including Quakers and the “French people.”16

Just over a decade later in Louisiana, after white locals and federal soldiers crushed an uprising of more than one hundred slaves, reports surfaced that the leader of the rebellion, a mulatto named Charles Deslondes, was in Saint-Domingue during the revolution; this is despite the fact that, Adam Rothman points out, no surviving primary evidence supports this claim.17 Regardless of the leader’s origins, one eyewitness described the relief of having averted “a miniature representation of the horrors of St. Domingo.”18 Last, in the wake of Denmark Vesey’s failed attempt at revolt in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1822, variations of the words Haiti and St. Domingo appeared nearly twenty times in one account of the official investigation, which officials published and distributed freely.19 The reaction to these failed stratagems suggests that, in the Old South, invocations of the Haitian Revolution were not meaningless tropes, but rather a sine qua non of any legitimate insurrectionary plot.

The pervasiveness of whites’ fears of a second Haitian Revolution presents us with a paradox. In the antebellum South demographics, geography, and other factors resulted in bondpeople revolting less frequently than enslaved people in ot...