![]()

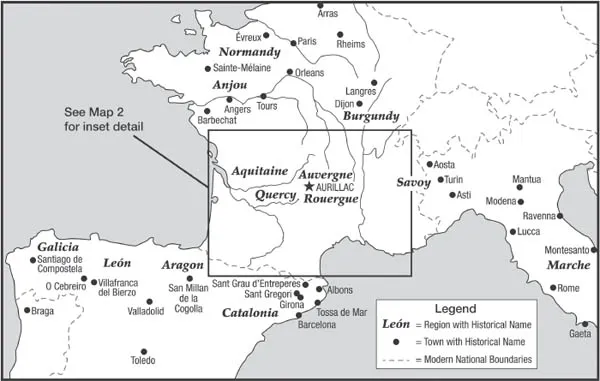

Map 1. Southwestern Europe.

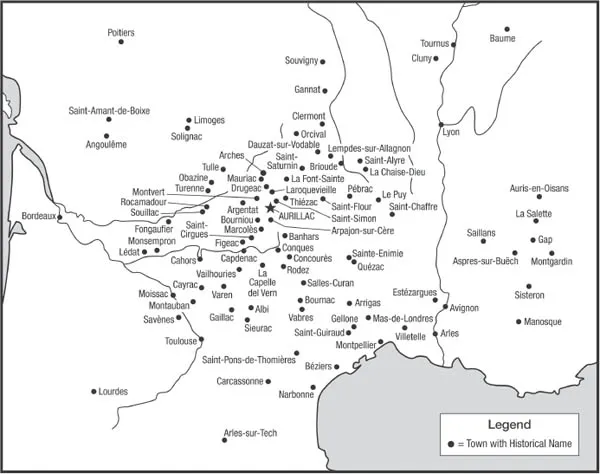

Map 2. Detail of Map 1, showing what is today southern France.

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Hagiography, Memory, History

High up in the French Alps, near the end of a twisting mountain road that snakes farther and farther up a steep mountainside from the village of Aurisen-Oisans, sits the medieval chapel of Saint-Giraud. No record survives of its origins: its first mention dates from 1454, when the bishop of Grenoble stopped there on his visitation through the district.1 It was never a parish church, and perhaps not a priory, although a sizable pile of stones next to the chapel hints that another structure, perhaps a residence, of which there is no historical recollection, once stood nearby. The chapel may be much older, since the bishop noted how deteriorated it appeared, and he ordered it restored. When I visited it in 2009 it showed only signs of decay—birds had even nested behind the altar. The chapel sits alone in its spectacular setting: abandoned, forgotten, silent (see fig. 1). No one with whom I spoke in the village could recall any event happening there, and no one knew anything about the Saint Gerald to whom the chapel was dedicated. The story of this little chapel is in many ways the story of Saint Gerald himself.

We know very little that is certain about Gerald of Aurillac. He was probably born in the middle of the ninth century and died in the early tenth.2 He spent most of his life in the mountainous region of Auvergne in the center of what is now France, which was then part of a larger Frankish empire. He belonged to one of the families of landowners and warriors that would become Europe’s nobility. He seems never to have married or had children, so before he died he left some or perhaps all of his wealth and lands to a monastery that he founded at the site that would become the modern city of Aurillac in the modern département of Cantal.

Within a generation of his death, Gerald was remembered as a saint. His piety and temperance in everyday life, his reputation for goodness and fair-mindedness, his chastity and pacifism, all contributed to his reputation—as did the reports of miracles he performed both during his lifetime and after his death. Within a century of his death the monastery he had founded and dedicated to Saint Peter and perhaps also to Saint Clement bore his name instead, as did a few dozen churches elsewhere, some in substantial towns like Limoges and Toulouse, others as far afield as Catalonia and Galicia. Without a formal process of canonization for saints yet in place, Gerald’s saintly memory was crafted, disseminated, and preserved especially through the biographies, sermons, and prayers written about him—hagiographical writings that were carried across the south of France and as far as Paris and Normandy, Venice and Lombardy.

Figure 1. Chapel of Saint-Giraud, Auris-en-Oisans (département of Isère). Photo by the author.

Gerald’s status as a lay saint was highly unusual. His was an age in which Christian sanctity was mostly equated with the life of the cloister or cathedral.3 It must have been difficult to imagine a lay male saint at a time when the basic features of manhood—eager participation in sex and violence—contravened Christian ideals so sharply. The result was a certain “anxiety” in relating Gerald’s sanctity, as Stuart Airlie puts it.4 Perhaps that anxiety took shape in the mind of the hagiographer, attempting to reconcile the values of the court to those of the cloister and offering a new model of lay holiness, as Barbara Rosenwein would have it.5 Or perhaps it derived from Gerald himself, as Janet Nelson suggests, unable to come to terms with the requirements of a secular masculinity but unwilling to abandon his worldly life fully.6

In the end, it may have been that equivocation that “undid” Gerald’s saintly memory. Other saints rose to prominence in the last centuries of the Middle Ages and beyond who exhibited a more inspiring or advantageous saintliness. The declining fortunes of the monastery of Aurillac also lost for Gerald the principal guardians of his memory. So forgotten was he in many of the places he had once been revered that new legends were crafted about him, tales at times vastly different from his original story. In the late nineteenth century, even as some revived Gerald’s memory, his cult acquired new features in keeping with idealized recollections of the medieval past. That is the trajectory of this book.

In contrast to Gerald’s obscurity among modern Catholic believers, the saint of Aurillac has attracted considerable scholarly attention, in part simply because there are only a handful of figures from the central Middle Ages for whom as rich a hagiographical tradition survives. The longer version of the Vita Geraldi (known to scholars as the Vita prolixior) has long been held to be the original version authored by Odo of Cluny in about 930; it has received the lion’s share of academic interest. Recent scholarship has added a sermon for Gerald’s feast day to the authentic writings of Odo. Relatively neglected is the briefer version of the vita (known as the Vita brevior), dismissed by most as uninteresting, overly condensed, and composed by some unknown and easily ignored forger in the late tenth century. Recently, additional miracle stories have been brought to light, composed no earlier than 972, and assigned to a second forger. Regrettably, these assumptions about dating and authorship are wrong, and I begin by correcting these errors, arguing that the briefer version of the Vita Geraldi belongs to Odo of Cluny, while the longer version, as well as the sermon and additional miracle stories, came from the hand of the infamous forger Ademar of Chabannes sometime in the 1020s.

Apart from these medieval texts, there is little else that survives from which to reconstruct the historical memory of Gerald of Aurillac. The monastic library at Aurillac that would have contained the best and most detailed records was sacked twice, at the hands of Aurillac’s townspeople in 1233 and again by Protestant Huguenots in 1567. Further losses happened during the French Revolution. Only a handful of manuscripts survive from the medieval library.7 Others survive elsewhere, especially at archives near the former priories that once belonged to the monastery of Aurillac, but there, too, little remains. The later chapters in this book, then, represent something of the challenge of reconstructing historical memory without much in the way of historical documentation—and a bit on the methods by which it might still be done.8

The complicated meanings attached to Gerald’s sanctity are the heart of this book. Gerald’s position between court and cloister placed him in the vanguard of a new broadening of saintly ideals for men: he was, insofar as we can tell, the first to be venerated as a saint for having lived a good life without having become a bishop or theologian, a monk or hermit, and his biographers both medieval and modern have pointed out this distinction.9 There were other noble lay male saints who lived before Gerald and who were revered for their holiness, it is true, but the writings about these men mostly date from much later centuries, and many of them were also remembered as martyrs, so they serve to confirm rather than to challenge Gerald’s precocity.10 Nonetheless, the tensions within Gerald’s model of sanctity are patent enough. On the one hand, one might see in Gerald the quintessence of the ethical code that all men of his era were exhorted to follow: to be both good Christians and good citizens.11 On the other hand, Gerald’s embrace of an ascetic lifestyle, his avoidance of sex, and reluctance to engage in battle were things that Carolingian piety would never have presumed.12 Both of these assessments may be fair. Perhaps like all saints, Gerald was at once a model for others and inimitable.13

The two sides of Gerald’s sanctity, his adoption of a monastic life while remaining outside the cloister and his renunciation of violence even while leading armies, served specific and important—if different, and historically contingent—needs for his hagiographers. Nonetheless, the placement of such equivocation within the legend of Gerald may have contributed to his undoing as a saint in the centuries after his death. After all, if a life lived in this world can be holy, why sacrifice oneself to an ascetic life? And if some forms of violence may be permissible to a good Christian, what others might also be? Gerald gave no easy answers to these questions. It is worth noting that the reshapings of Gerald’s legend in modern times often functioned as correctives to this ambiguity, redirecting Gerald’s memory into less uncertain channels.

This book is also, then, about the legacy that Gerald’s medieval hagiographers left behind. Before popes took control of the canonization process in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, hagiography provided a principal occasion for the commemoration of saints. Yet despite the subject’s importance, it is not entirely clear how these writings should be read. Scholars once saw in legends about the saints the projection of a past society’s heroic ideals.14 Many are now increasingly reluctant to assume that saints’ lives provide an unobstructed glimpse into any past society.15 The elusiveness and even outright unreliability of medieval hagiography have been brought home in a singular manner in the career of Ademar of Chabannes, who plays a central role in this book. Ademar forged a set of documents that described the life of a saint who never lived with a status that he never held and a history of devotion to him that never happened, and did it so successfully that only in the twentieth century was the deception uncovered.16

In this book I offer my own readings of hagiography and religious art as well as new ways of thinking about the central role that individuals have played in the production of saints. I attempt, in particular, to restore to medieval hagiographers their proper role in the crafting of the historical memory of saints.17 Jay Rubenstein laments the stereotype that medieval writers lacked “textual sophistication.” Instead, he encourages us to conjecture how even in the Middle Ages the truism that “all biography to some extent is autobiography” still applies: “The narrative of a person’s life grows out of beliefs of how a life ought to be lived, and a person’s beliefs about how a life ought to be lived inevita...