![]()

Chapter 1

Warning Beacons

I would describe the Northern Ireland problem as probably not much different than anywhere else. The more and more I try to understand conflict, the more and more I find resonances in other places and with other people…So can we have a single facet that is stark and in front of us that says: ‘Let's deal with the problem’? Well, of course we do. It's fear. Emotion. The intimacy of fear. So we try to remove the fear by creating the self-imposed apartheid that people demand. But none of it deals with the historical, the cultural, the economic, the social, none of it deals with any of those, so unless we have a multi-faceted approach to what our problem is, I don't think we can remotely begin to deal with our problem.

(David Ervine, former Member of the Legislative Assembly, Belfast, 2001)

This book compares five internally partitioned cities: Belfast, where “peacelines” have separated working-class Catholic and Protestant residents since “the Troubles” began in 1968; Beirut, where seventeen years of civil war and a volatile “Ligne de demarcation” made the city into a sectarian labyrinth; Jerusalem, where Israeli and Jordanian militias patroled the Green Line for nineteen years; Mostar, where Croatian and Bosniak communities split the city along an Austro-Hungarian boulevard into autonomous halves beginning in 1992, and Nicosia, where two walls and a wide buffer zone have segregated Turkish and Greek Cypriots since 1974.

In each city, urban managers under-estimated growing interethnic tensions until it was so late that violence spread and resulted in physical segregation. Though the walls, fences, and no man's lands that resulted were generally designed to be temporary, they have considerable staying power, forcing divided residents to grapple with life “under siege.” Unlike regular soldiers, destined to leave the battlefield in one condition or another, the inhabitants of wartorn cities confront their terrors at home without the means of retreat or escape. Even after politicians have secured a peace, the citizens struggle with losses and missed opportunities that are beyond compensation. Along the path to urban partition, a social contract between municipal government and residents is broken. The costs of renegotiation tend to be high.

Five Warning Beacons

Partitioned cities act as a warning beacon for all cities where intercommunal rivalry threatens normal urban functioning and security. Every city contains ethnic fault-lines or boundaries that give shape to “good” and “bad” neighborhoods and lend local meaning to “the other side of the tracks.” Since all cities reflect local demographics in spatial terms, each can be located somewhere on a continuum between perfect spatial integration and complete separation.

Evidence gleaned from the five cities examined here suggests that, given similar circumstances and pressures, any city could undergo a comparable metamorphosis. Accordingly, this comparative study offers guidance to urban managers who seek to avoid the enormous costs of physical segregation. Extreme case studies are useful because they reflect accelerated cause and effect dynamics that might otherwise require decades to observe (Benvenisti 1982: 5). Divided cities expose what lies in store for a large, and perhaps growing, class of cities on a trajectory toward polarization and partition between rival communities. In the early twenty-first century, this class includes Montreal, Monrovia, Dagestan, Washington, D.C., Baghdad, Dili, Bunia, Novi Sad, Kigali, Singapore, Cincinnati, Kirkuk, and Oakland.

Divided cities are generally linked with civil wars in which group identity is threatened. This type of war dominated the late twentieth century, leaving many cities vulnerable. Indeed, since World War II there has been a marked shift in global warfare trends from inter- to intrastate conflict: of 64 wars between 1945 and 1988, 59 were intrastate or “civil” wars, and about 80 percent of those who perished were killed by someone of their own nationality. During this same period, 127 new sovereign states were created and 35 new international land boundaries have been drawn since 1980 (Strand, Wilhelmsen, and Gleditsch 2003).

This splintering trend peaked around 1990 with the height of what has been called the “Third World War”—the systematic and violent disintegration of weak states into statelets controlled by regional ethnic rivals (Marshall 1999). As of 2007, about 23 protracted non-state, civil conflicts were ongoing, down from about 38 in 2003 and more than 90 in 1990. Of these, approximately 80 percent were grounded in contested group rights or threatened collective identity. Examples include recent hostilities in Sudan, Afghanistan, Angola, East Timor, Chechnya, Dagestan, Iraq, Ethiopia, Kosovo, India, Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, the Philippines, Ivory Coast, and Rwanda.

Civilian urban populations have been severely affected by this surge of interethnic warfare. Their burdens in relation to warfare appear to be growing. In World War I, for example, about 43 percent of all battle-related deaths were civilian. That figure rose to around 59 percent in the course of World War II, and since then—during a period when the number of intrastate conflicts surpassed the number of interstate conflicts—civilian deaths constituted approximately 74 percent of the wartime totals (White 2003). The scale and intensity of psychological trauma suffered by noncombatants has risen proportionately. Divided cities are emblems of this overwhelming loss, dislocation, and prolonged anxiety.

These trends appear to be borne out by Israel's unilateral partitioning program, which broke ground in 2002 amid escalating friction with Palestinian civilians. A sophisticated physical partition, called a “security fence” by its proponents and a “separation barrier” by critics, was about 60 percent complete in late 2007. The barricade's proposed length is 723 km along a new Israel-West Bank border, including up to 167 km sealing off the vulnerable eastern and northern flanks of Jerusalem.

The Symptom and the Illness

There has been symbiosis between cities and walls since the emergence of occidental urban culture. In divided cities, that relationship has deepened so much as to become dysfunctional. Internal partitions can be seen as causes, symptoms, or cures with respect to chronic urban problems.

The five divided cities examined here share more than fortified ethnic enclaves. Each was renowned for ethnic diversity and successful cohabitation prior to the outbreak of intergroup violence and the appearance of physical barricades. Though an ethnically mixed population is a prerequisite for urban partition, rival ethnic groups still manage to cooperate admirably in cities like Bombay, Phnom Penh, Mombassa, Kuala Lumpur, Kumasi, Jos, Bangalore, and Kinshasa. Why, then, do some cities resort to physical partition while others do not? One important factor may be the degree to which ethnicity conditions political affiliation:

in some places, identity politics came to define the logic of the political game, and in other places, it did not. In those places where it did, the odds of violence were higher…. The incentives and constraints offered by political institutions, and the strength of those institutions to follow through, largely determined those odds. (Crawford and Lipschutz 1998: 3)

The ethnic rivalries governing urban partitions often obscure more fundamental social tensions, like those felt between the professional and working classes, indigenes and settlers, or powerful minorities and marginalized majorities. Some scholars have even suggested that ethnically motivated discrimination and violence are provoked by “sectarian political entrepreneurs” whose political fortunes rely on intergroup competition and antagonism (Crawford and Lipschutz 1998). Indeed, ethnic conflict may appear intractable more because it is artificial than because it is endemic.

Scholars of ethnic conflict in Lebanon, Israel, Bosnia, Northern Ireland, and Cyprus debate whether partition is the result of conspiratorial politics or homegrown prejudice. (Of special usefulness are the works of Henderson, Lebow, and Stoessinger 1974; Horowitz 1985; Schaeffer 1990; Crawford and Lipschutz 1998; Cleary 2002.) The problem of false dichotomies is an important one in most divided cities, since a failed cure is certain to follow a faulty diagnosis.

One Belfast politician described a common anxiety:

We are destined to get worse, not better, for as long as there is the concept of fear and siege. So if fear is, at the core, the most dangerous emotion…then remove the fear. Now, how do you do that? Is it done by walls? Is it done by education? Is it done by being inventive about how you share the land? I'm not sure that I have any of the answers—plenty of the questions. (Ervine 2001)

What can urban managers do when a group of Belfast teenagers light a bonfire of trash and wood in an empty lot along one of the city's many Protestant-Catholic interfaces? Their excitement grows if members of a rival group from the adjacent neighborhood appear at the scene. Alcohol is consumed, taunts are exchanged, and someone throws a stone. When a riot ensues, older community members on both sides are summoned in a ritualized chain reaction. As confrontation escalates slowly over weeks and months, the stakes are gradually raised and houses on one or both sides are attacked, terrorizing the inhabitants, who typically have no connection with the violence outside. These victims are innocent but are simply too close to the interface, so they bear the brunt of social, physical, and psychological traumas. Faced with such a chronic problem, the citizens petition their parliamentary representative for an interface wall. If their case is sound, the municipal government allocates the necessary funds and commissions another peaceline. Typically, the restless teenagers at the center of the drama move on to the next empty pocket and the cycle begins again. As a result, more than thirteen major barricades have been erected between Catholic and Protestant residents in Belfast, and none have yet been dismantled.

This Belfast scenario illustrates a common concern among the managers and besieged residents of divided cities: the need to stem physical violence at hostile interfaces. Policymakers often feel compelled to provide protection in the form of barricades once conventional approaches fail. In many instances, threatened citizens or paramilitary groups have already erected ad hoc barriers. Whether unofficial or sanctioned, the physical partition is employed to contain a crisis that has overwhelmed existing systems designed to maintain order and protect urban residents in an evenhanded way.

One reason municipal governments are hesitant to address the subject of partition is that the barricades are a measure of their own failure to fulfill a basic political mandate. Another is that the walls, whether illicit, scandalous, or ugly, tend to curb intercommunal violence more cheaply and effectively in the short term than police surveillance. They solve a profound, longstanding problem in a superficial, temporary way.

If such partitions worked over the long haul, urban dividing walls could be considered an unfortunate but effective response to ethnic conflict. However, as passive security devices they are a failure for the municipal government, and this is just one of many reasons why their construction should be questioned. In many cases, these partitions also postpone or even preclude a negotiated settlement between ethnic antagonists because they create a climate of dampened violence, sustained distrust and low-grade hostility. Urban partitions seem to reduce violent confrontation while justifying fear and paranoia. If there were no actual danger, this logic suggests, the walls would no longer be standing. In this way, the partition becomes the emblem of threat as much as a bulwark against it. The communities behind these walls often witness their neighborhood evolve from an arena of violent conflict into an insulated pressure cooker.

Voluntary and involuntary habits of segregation, with visible and invisible forms, become mutually reinforcing. In Nicosia, even the anger of older Cypriots that has been generated by their personal knowledge and history seems preferable to the idle prejudice of younger citizens whose cynicism is inherited and untested by direct contact. The ignorance of the unknown but stereotyped “other” behind urban partitions is a core ingredient for future conflict, and its toxic effects on the social atmosphere of the city must be weighed in relation to the short-term benefits of division, most of which accrue to the city's managers rather than its citizens. If instances of interethnic violence were rare or isolated, these concerns would be of merely anecdotal value. However, the statistics related to intergroup conflict on a global level point in the opposite direction.

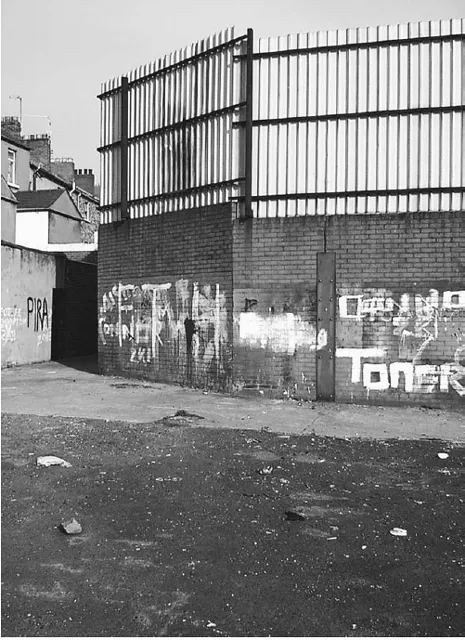

Figure 1.1. Ethnic partitions in Belfast, like this one near Grosvenor Road, govern everyday relations between neighbors and create dangerous, wasted spaces. Authors.

Long treated as anomalies, divided cities are linked to each other by clear and coherent patterns. Some of these are summarized in Chapter 10. Urban partition results from concerns found in almost every city, such as ethnicity tied to political affiliation, institutional discrimination, physical security, fair policing, and shifting relations between majority and minority ethnic communities.

Even a casual scan of international affairs this early in the twenty-first century reveals that urban communities torn and traumatized by physical segregation are multiplying quickly. Brussels remains the would-be trophy of separatist parties in Wallonia; Montreal could be caught in a similar tug-of war in Quebec; Los Angeles has yet to confront the racial fractures exposed by popular violence in the 1990s; the Serbian and Albanian residents of Mitrovica have split themselves on either side of the Ibar River; riots between the Hausas and Yorubas of Nigeria have ravaged Lagos; Hindus and Muslims clash routinely in Ahmedabad, though they dispute the Ayodhya religious complex hundreds of miles away; sovereignty in Baghdad is contested by several ethnic and religious groups in the current wave of instability there; in 2001 Cincinnati's racial fault-lines were activated in the wake of discriminatory police brutality. These are but a few of many examples worldwide.

In reply to such lapses in traditional urban peacekeeping, urban communities resort to riot, revolt, threats of succession, and paramilitary activity. New walls between rival ethnic groups are constantly emerging, while old scars are stubborn in healing. The causes for rivalry, along with the evidence of forsaken alternatives, generally go unrecognized or are long forgotten.

Politicians—both those embroiled in the ethnic conflicts and those who attempt to intercede on behalf of the international community—often become mired in short-term policy fixes that are designed in response to a crisis. Official advocacy of urban partition as a reply to ethnic conflict was once shunned but is now common. Physical segregation has emerged over the last fifty years as one of the most popular and most myopic solutions to intergroup violence in the urban environment.

Chinagraph Frontiers

Cities can be divided in many ways. Some have been shattered by a wax pencil in the space of an hour, remaining split for decades by a “chinagraph frontier,” as in Nicosia. Others are restless battlegrounds scored by informal boundaries of varying degrees of permanence. Some cities develop sealed, semipermeable boundaries in response to particular episodes, seasons, or political events. In Belfast it has been shown that “movement patterns and feelings of threat depended on the level of tension or violence locally” and that “the level of tension or violence increased at different times of the year” with special concerns centering on traditional anniversaries, marches and parades (Murtagh 1995: 217). All such cities use roads, mountains, rivers, and open spaces to reinforce informal systems of physical segregation, sometimes complemented by engineered barricades.

Arbitrary lines drawn on a map—due to the urgency of a compromise, the necessity of war, or the tremor of a human hand—result in urban minefields navigated daily by residents who are unable to avoid them. In Jerusalem, the arbitrary “thickness” of the Green Line, as drawn on the armistice map of 1948, generated confusion that persisted for many months after the formal division of the city, and several people were wounded after wandering by accident inside the “width of the line” (Benvenisti 1996: 61). These boundaries isolate communities that know each other, rely on each other and overlap with one another.

Cities are rarely divided by their own citizens in isolation. They are typically the product of external forces acting on a city with the intent to protect it, save it, claim it, demoralize it, or enlist it in a larger struggle from which it cannot benefit. Lines become walls and walls govern behavior. Total separation ultimately makes bigotry automatic, functional division habitual, and deepening misunderstandings likely. Walls are both a panacea and poison for societies where intergroup conflict is common, but over time it is their toxicity that tends to prevail in social relations. The Green Line in Nicosia was called an “unremitting obstacle to progress toward normalization between the two communities” (Harbottle 1970: 67) by one observer, and this characterization can be applied to all five cities examined here.

Although their social impacts are nearly identical, urban partition lines bear little outward resemblance to one another because their origins differ greatly. Some dividing lines, like those in Jerusalem and Nicosia, were hand-drawn on a map by appointed negotiators. These lines generally require physical barricades, since they often carve their way through shared spaces and seem arbitrary or counterintuitive in their meanderings through contested urban territory. Being the result of “rational” design, such partitions are typically constructed as parallel barricades that separate a barren neutral zone in the city center. Others, like the dividing lines in Belfast, Mostar, and Beirut, are place-specific remnants of interethnic violence, often lacking walls and fences. These demarcations tend to be slow to emerge, slow to disappear, and unofficial. Local residents are conditioned by habit and painful experience to avoid them. Belfast provides a good example of a city where the municipal government has yet to represent the peacelines separating Catholics from Protestants on any map, though millions of dollars are appropriated to construct, enlarge, and maintain these walls in response to public petitions.

In Beirut, the Green Line was an official military boundary that proved quite inadequate to create protected zones for urban residents, since paramilitary warlords swiftly subdivided larger Christian and Muslim sectors with their own boundaries determined by the shifting location of snipers’ nests. In Mostar, the largest north-south street became the front line between military and paramilitary forces. A wall was never erected: open space, uniquely hazardous in a dense Ottoman city fabric, constituted the primary barricade along the line. Had this front line slipped slightly eastward to the natural partition—the Neretva River gorge—the elimination of the city's native Muslim population would have been assured.

Lending additional urgency to the study of divided cities is the predictable nature of their transition from healthy, integrated places to physically partitioned ones. While sudden and unexpected episodes of violence often herald the final stages of intercommunal isolation, the fault-lines activated during these cataclysmic periods are rarely unfamiliar to residents. Still, the divided cities examined here were not destined for partition by their social or political histories; they were partitioned by politicians, citizens, and engineers according to limited information, short-range plans, and often dubious motivations.

Until the onset of its crippling civil war in 1991, Mostar was an emblem of interfaith tolerance in the Balkans, representing the educated observer's last guess for the city most likely t...