![]()

Chapter 1

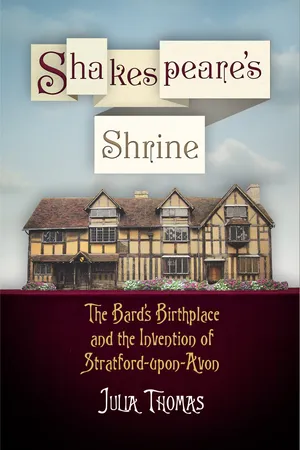

The Birth of “Shakespeare”

Identity Crisis

Before the Birthplace was restored in the middle of the nineteenth century, a sign hung on the exterior wall between the window of a bedroom and the butcher's hatch: “The Immortal Shakspeare,” it announced, “was born in this house.” This sign established the provenance and authenticity of the building, marking the beginnings of the Stratford tourist trade. Some detractors suggested that the erection of this board was a conspiracy on the part of the townspeople to bring visitors into Stratford; others identified it as the work of an enterprising occupant of the house.1 Despite its questionable origins, however, there is a sense in which the sign's statement about the origins of Shakespeare might have some validity: Shakespeare, or rather, an idea of what “Shakespeare” meant, was “born” in this house and in the debates and conflicting representations that surrounded it.

The history of the Birthplace involves a transition from an essentially allegorical, metaphorical, and metropolitan eighteenth-century representation of Shakespeare's immortality to a biographical and provincial sense of his mortality that became most prominent in the middle of the nineteenth century. The Victorians drew on earlier, mutually reinforcing conventions of viewing Shakespeare as godlike and the Birthplace as a site of pilgrimage and worship: the divinity of Shakespeare sanctified the house, while the house, as shrine, emphasized Shakespeare's otherworldliness. As one mid-Victorian writer remarked of the Birthplace, “There is a sense in which human genius consecrates the soil on which it flourished, and the material objects with which, while tabernacled in the flesh, it happened to be associated.”2 But Shakespeare, as this writer also serves to remind us, was not just a genius: he was human too. He might have been “tabernacled in the flesh,” but he was flesh, and the Birthplace was the origin of that flesh. In seeming opposition to the insistence on immortality, the Birthplace became the symbol of Shakespeare's very mortality, the fact that he had once lived, breathed, and been part of a family. This cultural shift depended upon an investment in biography as an explanatory mechanism and, more specifically, on the importance of childhood in the writings that make up Shakespeare. As the home of Shakespeare's formative years, the Birthplace acted as the catalyst for “memories” of his life and was the kernel of a movement to domesticate Shakespeare that grew as the century wore on.

These multiple identities of Shakespeare emerged from and formed a key component of the growing connection between bard and Birthplace, which coincided with a more general attempt to unite people and places in the rise of the homes and haunts genre. Travel writing described visits to locations related to famous figures and thereby encouraged an association between the site and the person, so much so that, as one contemporary writer commented, the two become “inseparably connected” in the imagination.3 In her account of literary tourism, Nicola J. Watson charts the development of the homes and haunts tradition from the eighteenth century as a textual movement that paralleled the burgeoning popularity of actual trips to these locations.4

The identification of the setting of Shakespeare's birth, though, does not fully account for the complex links that came to exist between this particular architectural edifice and “Shakespeare.” Michel Foucault refers directly to Shakespeare's Birthplace, arguing that the discovery that Shakespeare was not actually born in the house would not affect what the author's name meant and how it circulated, whereas if it were proved that Shakespeare had not written the sonnets there would be a significant change.5 Foucault's statement seems incontrovertible: the notion of what “Shakespeare” means would, of course, be modified if texts were proven not to have been written by him. However, Foucault's dismissal of the significance of the house, while perhaps justified today, would not apply to its Victorian reality. In the nineteenth century, the meanings of the building were in these points of connection which linked “Shakespeare” and the Birthplace, and, in so doing, fostered the contradictory notions of the poet that were inscribed in that little wooden sign: Shakespeare as immortal, with all the connotations of genius and divinity that came with this status, and Shakespeare as a real being, whose birth took place within these hallowed walls.

Immortal Willy

One of the earliest references to the material traces of Shakespeare's life in Stratford is in William Dugdale's monumental The Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656). Dugdale refers in detail to the tomb of Shakespeare in Holy Trinity Church and includes the first pictorial representation of the monument, remarking that “this ancient Town … gave birth and sepulture to our late famous poet Will. Shakespere.”6 Dugdale does not, however, mention the Birthplace, and the building does not make an appearance until over a century later in 1759 when Stratford's local surveyor, Samuel Winter, sketched the earliest plan of Stratford and identified the “House where Shakspeare was born.”7 Winter's map, which pinpoints all of Stratford's prominent streets and buildings (including the White Lion pub, which was located just up the road from Shakespeare's house), suggests that by 1759 the Birthplace had been identified as such and that the property was worthy of note, even if this was within the context of a provincial town plan.

It was not, then, until the second half of the eighteenth century that the attempt to construct and commemorate Shakespeare within the environs of Stratford-upon-Avon by using and exploiting the resources of the town really began. The key event in this movement was the Shakespeare Jubilee of 1769, which cemented the connections between Stratford and Shakespeare and signaled the formal beginnings of the tourist trade in the town.8 In the words of Nicola J. Watson, “the Jubilee codified, expanded, and boosted a small-scale provincial industry by successfully linking different Shakespeares—the Shakespeare of the London stage, the Shakespeare of the printed page, the rural Shakespeare of Stratford, the increasingly mythic ‘Shakespeare’ praised by critics and nationalists—within a multimedia spectacular staged in a single location.”9 This “multimedia spectacular,” organized by David Garrick, who had been approached to raise money for the purpose of erecting a bust of Shakespeare in a niche in the front of the town hall, effectively defined Stratford as the center of what became known as bardolatry. It also, as Watson indicates, established a discourse that articulated and shaped the growing bond between Shakespeare and Stratford.

Part of this bond was focused on the Birthplace. While the building on Henley Street, as the 1759 plan attests, was regarded as the Birthplace before the arrival of the charismatic actor in Stratford, no such tradition existed about the exact part of the house in which Shakespeare was born. Garrick, with typical bravado, strode into the building and confidently pointed out the room.10 He went on to hang an emblematic transparency from the window of this “birthroom” showing the sun struggling through the clouds to enlighten the world, underneath which was printed a quotation derived from The Third Part of Henry VI: “Thus dying clouds contend with growing light.”11 Behind this glorious transparency glowed the warm light of commerce as Garrick's friend, the publisher Thomas Beckett, took his place as official Jubilee bookseller, selling a large supply of books and pamphlets, including a quarto edition of Garrick's Ode on Dedicating a Building and Erecting a Statue to Shakespeare and the collection of fourteen Jubilee songs.12 Garrick also had plans for a fancy-dress parade past the Birthplace, which eventually had to be canceled because of bad weather.

Although the property was allotted a role in the Jubilee, it was not as eminent a venue as Holy Trinity Church or the huge octagonal amphitheater erected on the banks of the River Avon especially for the event. Designed in imitation of the rotunda which formed the centerpiece of the Ranelagh pleasure gardens in London, the amphitheater could seat one thousand people, had an orchestra pit for one hundred, and was decorated with a chandelier of eight hundred lights that hung from the dome. As stylish a theater as this rotunda was, during the three days of the festivities none of Shakespeare's plays was performed there, for “Shakespeare” and what he signified were more important than the drama itself. Indeed, what “Shakespeare” meant was there for all to see in the huge transparencies, illuminated by lamps, that adorned the front of this amphitheater and showed three allegorical paintings after compositions by Joshua Reynolds: Tragedy on the one side, Comedy on the other, and, in the central panel, Time leading Shakespeare to immortality.13

This iconography and language of immortality dominated the Jubilee festivities of 1769 to the extent that one of the songs Garrick performed celebrated the immortality of a mulberry tree which was said to have been planted by the bard's own hands in the grounds of New Place: “And thou like him immortal be!” was the catchy refrain.14 Garrick's exclamation was not far from the truth since the wood from this tree continued to supply an endless number of relics, despite the fact that it had been chopped down a decade earlier by the infamous Francis Gastrell (whose destructive tendencies were then directed to the house itself). With Shakespeare revered as an immortal being, Stratford was defined as his shrine, the Jubilee applying the religious terminology used to label Shakespeare to descriptions of the town itself. This association was explicit in many of Garrick's lyrics: at dinner on the second day of the festivities, the assembled guests joined in with the lines “Untouched and sacred be thy shrine,/Avonian Willy, bard Divine.”15 The Avon was treated as holy water, some trees on the bank being cut down by express permission of the duke of Dorset so that visitors could get a better view of the river.16

Garrick's definition of Stratford as a sacred shrine might have jarred with the weary and wet participants of the Jubilee. For all its grand planning, the event succumbed to the British weather and was a complete washout. Some said that the thirty cannons lined up on the banks of the Avon made such a racket that they caused a shattering effect on the clouds.17 Accommodation could not be found, prices soared, and coaches got stuck in mud trying to leave the town. Garrick himself was obviously jaded by the event. When he was asked to organize another jubilee by the Stratford Corporation, he declined, but offered some sage advice on how they could best honor Shakespeare in future: “Let your streets be well paved and kept clean, do something to the delightful meadow, allure everybody to visit the Holy-land, let it be well lighted and clean underfoot, and let it not be said, for your honour and I hope for your interest, that the town which gave birth to the first genius since the creation is the most dirty, unseemly, ill-paved wretched looking place in all Britain.”18

For Garrick and his guests, Stratford was far from the ideal tourist destination, and it would take a century or so before his advice about cleaning up the town was heeded. His cynical comments (one can almost imagine him penning this letter wrapped up in several layers of clothing with his feet soaking in a tub of hot water) might explain why, although the Jubilee brought people to Stratford from different parts of Britain and especially from London, it did not result in an exponential increase in visitor numbers over the course of the following years. Tourism to Stratford remained an elitist activity, undertaken by the educated and wealthy visitor, or by the accidental tourist, travelers being lured inside the Birthplace because of its proximity to the White Lion, one of the major coaching inns on the great North Road, the main route through the country from Ireland and northern England. In fact, the irony of Garrick's Jubilee is that it moved Stratford to London, when Garrick transferred the festivities to the theater in Drury Lane, where they could not be disrupted by inclement weather or uncivilized locals.19 This recreation of the Stratford events within the security and comfort of a London theater was a huge success and resulted in almost one hundred performances during the course of the season. The show did contain some elements of the uncomfortable reality of the Stratford Jubilee: it opened with a scene in an inn-yard where the inhabitant of a post-chaise complains that he cannot get a lodging house for the night and is forced to sleep in his carriage.20 Largely, however, the performance allowed for a celebration and veneration of Stratford, which was intensified because of its safe distance from the town.

The idea of Stratford and Shakespeare's connection with it that emerges from the Jubilee is primarily a metropolitan one, with Shakespeare hailed as “that demi-god!/Who Avon's flow'ry margin trod.”21 Eighteenth-century Stratford might have been more muddy than “flow'ry,” but its idealization in the Jubilee festivities, along with Shakespeare's growing status as a divine entity, meant that the town had become the “Holy-land.” And if Stratford was the “Holy-land” then the Birthplace, with its sparse interior, roughly timbered walls, and rudely paved floors, was regarded as the site of the nativity. Numerous texts and paintings glorified the infant Shakespeare, so it was not such a jump to venerate the setting of his birth in a similar fashion.22 This trope continued into the nineteenth century. One visitor in 1824 described the tourist who comes to the house “as a pilgrim would to the shrine of some loved saint; will deem it holy ground, and dwell with sweet though pensive rapture, on the natal habitation of the poet.”23

By the time of Victoria's ascension, the meanings of the Birthplace and the meanings of Shakespeare were so entangled that they became interchangeable. Frederick W. Fairholt, who visited the Birthplace in 1839 and went on to write one of the first guidebooks to Stratford, called the property the “immortal house.”24 In a letter to the editor of the Examiner in 1847, the poet Walter Savage Landor's description of the building makes explicit its connection with another glorious birth: “This edifice contained that illustrious cradle near which all human learning shines faintly, and where lay that infant who was destined to glorify and exalt our greatest kings.”25 Such religiosity is visually embodied in Thomas Nast's evocative painting The Immortal Light of Genius (1896), which was commissioned by the actor Henry Irving.26 Nast's image, which is set in the birthroom, shows the bust of Shakespeare radiating with a supernatural glow as the figures of Comedy and Tragedy present laurel wreaths. The genius of Shakespeare, this picture suggests, will never be extinguished; it lives on in the light that emanates from the bust and shines on the bare walls and floorboards of the Birthplace.

This vocabulary of worship and pilgrimage was, of course, a rhetorical device: Shakespeare was not really a divine entity, and the Birthplace was a secular rather than religious shrine, but so effective was the language of spiritual devotion that the boundaries between the secular and the sacred began to blur. The “Bibliolatry of Bardolatry,” as Charles LaPorte has recently termed it, was a characteristic feature of the way that the Birthplace was represented in this period.27 Such pseudo-religiosity did not go entirely unobserved. A contemporary visitor to the house, who was compelled, as were many, to...