![]()

CHAPTER 1

Farewell to the Party of Lincoln? Black Republicans in the New Deal Era

Frederick Douglass’s well-known adage that “the Republican Party is the deck, all else is the sea” reflects the significance of the Party of Abraham Lincoln to black politics for more than five decades after the Civil War. Even by the 1930s, when the Grand Old Party lost millions of black voters to Franklin Roosevelt’s Democratic Party, many African Americans still lingered on the GOP deck. Far from being an aberration in black communities during the 1930s and 1940s, Republicans remained deeply entrenched in the African American political landscape, leading southern “Black-and-Tan” organizations, running competitive campaigns in municipal and state elections, and lobbying for civil rights. As politicians, black Republican officials like Kentucky’s Charles W. Anderson and Chicago’s Archibald Carey, Jr., sponsored, and sometimes secured, passage of groundbreaking state and local civil rights legislation. Others, such as Robert Church, Jr., and Grant Reynolds, partnered with A. Philip Randolph and other independent black leaders in protest against racial discrimination. Though they were not members of Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition, black Republicans remained integral figures inside communities across the nation, and their emphasis on eliminating Jim Crow and other blatant forms of institutional racism remained popular with their allies in the black middle class.1

In the Reconstruction years that followed the Civil War and the end of slavery, black Republican voters and politicians became fixtures of southern politics. During these transformative years of the late 1860s and 1870s, approximately 2,000 African Americans held public offices that ranged from county administrators to senators. Black Republican P. B. S. Pinchback served as governor of Louisiana, and U.S. senators Blanche Bruce and Hiram Revels represented Mississippi. Over half the politicians elected in South Carolina between 1867 and 1876 were black, including Representative Joseph Rainey and Senator Robert Smalls, who were joined in Washington, D.C., by African Americans representing southern states spanning from Virginia through the Deep South. These politicians, on both the federal and state levels, played instrumental roles in the passage of the south’s and the nation’s first civil rights laws and progressive reforms in education, orphanages, asylums, and economic development.2

Black Republicans were also the targets of systematic violence at the hands of ex-Confederates intent on restoring white supremacy in the upended South. In 1873, an estimated one hundred and fifty African Americans were killed by a mob of white Democrats in Colfax, Louisiana, following a contested election. Similar massacres occurred across the South from New Orleans to Wilmington, North Carolina, through the end of the century. Terrorist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan served as Democratic proxies bent on ridding the South of black voters and their white Republican allies. By the 1890s, their campaign of violence and intimidation had paid off, as Democratic politicians swept into state offices, where they rolled back voting rights, instituted racial segregation, and turned a blind eye to murderous lynch mobs resolved to keep African Americans “in their place” of inferiority. This racially oppressive Jim Crow South, built and preserved by Democrats, would remain the defining characteristic of southern politics, society, and culture for the next half century.3

In the face of Democratic resurgence, the national Republican Party abandoned the South, and shifted its focus to northern businessmen and to industrial development. Despite this betrayal, the GOP remained one of the nation’s only institutions for black political advancement. In the South, where many African Americans could not even vote, black elites still controlled the skeletal remains of Republican parties in many states throughout the early decades of the twentieth century. Among their primary roles was that of patronage dispenser during the administrations of the Republican presidents who governed all but eight years from 1897 to 1933. “Black-and-Tan” organizations, a name given to southern Republican parties by Democrats, supported the northeastern wing of the party as delegates to national conventions, and in return were rewarded with financial assistance and political appointments. They were often responsible for recommending federal marshals, attorneys, and judges in their respective states, and were even privately treated with deference by Democrats seeking federal jobs.4

While the influence of black Republicans within southern politics was limited to patronage, they had a modicum of power inside the national party infrastructure. As residents of rural states that elected few Republicans to national office, they held disproportionate representation within the Republican National Committee (RNC). According to GOP rules, regardless of population, each state was allotted two members on the committee, who set the party’s agenda by planning the national convention, allocating state delegates, and running the party nominee’s presidential campaign. As state representatives within the GOP infrastructure, some black southerners had connections that extended deep into the halls of Washington, D.C., and were among the few African Americans of the early twentieth century with the ability to leverage white politicians for a share of spoils and patronage. Though a nation shrouded in discrimination forced many Black-and-Tans to adopt a public stance that did not openly challenge white supremacy, members wheeled-and-dealed behind the scenes for piecemeal benefits on behalf of their communities.5

In Georgia, for example, Henry Lincoln Johnson and Benjamin J. Davis, Sr., controlled the allotment of federal patronage from the 1910s through the 1930s. Davis represented the state as a delegate to every Republican National Convention from 1908 until his death in 1945, and served as one of Georgia’s two members on the national committee and as secretary of Georgia’s Republican Executive Committee. Other African Americans in high-ranking positions included William Shaw, secretary of the Georgia Republican State Central Committee, and national committeewoman Mamie Williams. Supported by Atlanta’s large population of middle-class African Americans, Georgia’s Black-and-Tan leadership was among the most active in the South. Davis and Shaw made the black vote an important factor in Atlanta’s municipal elections through intensive registration drives, and Davis, a founding member of the Atlanta branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and an occasional member of the Platform Committee, successfully pressed the national party to include anti-lynching legislation on party platforms.6

African Americans in other southern states possessed similar positions of influence within GOP ranks. Little Rock attorney Scipio Jones controlled federal patronage in Arkansas for almost three decades, and served as a delegate to national conventions into the 1940s. In South Carolina, N. J. Frederick served as Richland County (Columbia) commissioner and as a delegate to national conventions throughout the 1920s and 1930s. As secretary of the Republican State Central Committee and secretary of the Orleans Parish Central Committee, Walter L. Cohen led the Louisiana Republican Party from 1898 until his death in 1930, and was appointed to one of the most valued federal posts in the South, comptroller of customs for the Port of New Orleans.7

Black control of southern Republican organizations did not always go unchallenged. Their opponents, self-professed “Lily-Whites,” consisted mainly of southern industrialists who were skeptical of Democratic populist appeals, and sought to “purify” the GOP of African Americans in order to bring competitive two-party politics to the South. On issues of white supremacy, there were few differences between Lily-Whites and race-baiting Democrats. Though they assumed control of the GOP in some states, such as North Carolina, their ascendance was far from guaranteed, as the case of Mississippi demonstrates. Despite fierce Lily-White opposition in the Magnolia State, a delegation led by black attorney Perry W. Howard was seated at the 1924 Republican National Convention, and Howard was elected to represent the state alongside an African American woman, Mary Booze, on the national committee. Locally, S. D. Redmond, a black dentist from Jackson, became chairman of the state executive committee, a post he held until 1948. Though Lily-Whites would continue to challenge Howard’s leadership, the victories of his Black-and-Tan faction in the mid-1920s solidified his power for the next three decades. Howard attended all but one national convention as a delegate from 1912 to 1960, and served as one of Mississippi’s two members on the national committee until his death in 1961, the longest tenure of a committeeperson in party history.8

Despite being a fierce competitor of Lily-Whites, Howard was mostly silent on the issue of civil rights. In 1921, he became the highest paid black federal employee, when President Warren G. Harding appointed him special assistant to the attorney general. After moving to Washington, D.C., he rarely returned to Mississippi, and, unlike Benjamin Davis, Sr., of Georgia and other more race-conscious Black-and-Tans, Howard declined to challenge his party on issues of race, and even joined conservatives in opposing anti-lynch legislation. His accommodationism appealed to Mississippi’s Democratic establishment, who defended him in 1928 after he was indicted on charges of selling federal jobs. Not only did Democrats receive over 90 percent of Howard’s appointments, but they also enjoyed the presence of an allegedly corrupt black official as the head of the state’s Republican Party.9

As much as Howard represented the most dubious example of Black-and-Tan politics, the Republican Party of neighboring Tennessee sustained the hope many African Americans placed in the GOP. The state’s party was shared by traditionally Republican Appalachian counties in the east and Black-and-Tans in the west led by Robert R. Church, Jr., of Memphis. The son of one of the wealthiest black men in America, Church retired from the family-owned Solvent Savings Bank as a twenty-seven-year-old millionaire, and devoted his life to politics. He was first elected as a delegate to the 1912 Republican National Convention, and over the subsequent decades served on the state Republican Executive Committee and the Republican State Primary Board.10

His standing in the party was enhanced by his ability to finance a large share of southern and midwestern Republican campaigns with his own money, or money he raised via his family’s extensive business network. Preferring to wield influence behind the scenes, and in spite of vehement opposition from state Democrats, Church secured patronage for major southern appointments, including several racially progressive federal judges and the U.S. attorney general for West Tennessee. He also recommended African Americans to positions inside his district and within the federal government. Because of Church, African Americans made up almost 80 percent of Memphis’s mail carriers in the 1920s, who received the same salary and pension as their white coworkers. On the national level, he secured positions for Charles W. Anders as the internal revenue collector for New York’s wealthiest district and James A. Cobb as judge of the Washington, D.C., municipal court. One of the South’s most rabid segregationists, Alabama senator James Heflin, gave inadvertent homage to Church’s influence when reciting a derogatory poem on the floor of the Senate in 1929: “Offices up a ’simmon tree / Bob Church on de ground / Bob Church say to de ’pointing power / Shake dem ’pointments down.”11

In addition to securing federal posts for African Americans, Church was deeply concerned with issues of black social and political equality. A close friend of NAACP executive secretary James Weldon Johnson, Church served on the organization’s national board of directors and contributed to its growing presence in the South by subsidizing nearly seventy branches in fourteen states. He also organized the Lincoln League of Memphis to ward off Lily-White opponents in February 1916. The league registered almost 10,000 voters by the fall, and black Republicans outnumbered Lily-Whites by a four-to-one margin, comprising almost one-third of Shelby County’s total electorate.12

Three years later, Church expanded the league into a national organization comprised of some of the country’s most influential African Americans. In February 1920, four hundred delegates attended the Lincoln League’s first national convention in Chicago, and demanded that the Republican National Committee increase the presence of African Americans in the forthcoming presidential campaign. RNC Chairman Will H. Hays responded by appointing five members of the league, Church, James Weldon Johnson, Roscoe Conkling Simmons, S. A. Furniss, and William H. Lewis, to the Advisory Committee on Policies and Platforms. On election day, Church further demonstrated his importance to the GOP when black voters helped secure President Harding’s victory in Tennessee, the only southern state to swing to the Republican column.13

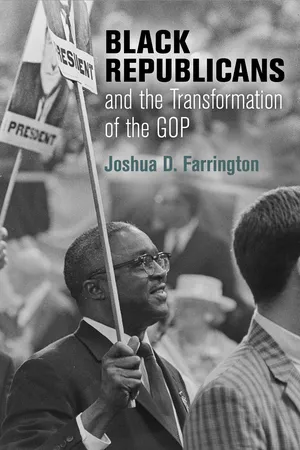

Figure 1. Black-and-Tan leaders outside Robert Church, Jr.’s Solvent Savings Bank and Trust in Memphis, Tennessee, circa 1920s. Left to right: Church, Henry Lincoln Johnson, Roscoe Conkling Simmons, Walter L. Cohen, John T. Fisher, and Perry W. Howard. M.S.0071.038087.001, Robert R. Church Family of Memphis Collection, University Libraries Preservation and Special Collections, University of Memphis.

As Church assumed a national role in the 1920s, his pupil, George W. Lee, took control of duties in Memphis. A World War I veteran commissioned by the Army as a lieutenant, Lee founded a successful insurance company in the 1920s. “Lt. Lee,” as he referred to himself, secured the promotion of the county’s first black rural mail carrier, post office station superintendent, and foreman, and the mid-South region’s first assistant postal distribution officer. An active member of the Memphis NAACP and Urban League, Lee also drafted resolutions for the national Lincoln League demanding that the Republican Party increase federal appointments of African Americans, pass anti-lynch legislation, and reach out to black voters by combating Jim Crow. Like Church’s, Lee’s partisan affiliation was not based on sentimental attachment, but, in his own words, he sought to use “the machinery of the Republican Party to advance the cause of the Negro.”14

African Americans in northern cities also found positions within Republican ranks. Black Republicans held influence in Seattle, Washington, which had a long history of progressive Republicanism that reached out to black voters, where they continued to obtain local and state patronage positions from the national party throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Well into the late 1930s, African Americans in Philadelphia remained a vital constituency of the city’s Republican machine, whose black supporters included E. Washington Rhodes (a state legislator and publisher of the Philadelphia Tribune) and city magistrates J. Austin Norris and Edward Henry. Black Republicans also played a prominent role in Chicago, home to one of the largest GOP machines in the country. Roscoe Conkling Simmons, nephew of Booker T. Washington and president of the South Ward Republican Committee, politically organized waves of black immigrants fleeing the South, and procured licenses for black undertakers, barbers, and pharmacists. His work culminated in the 1928 election of black Republican Oscar DePriest to the U.S. House of Representatives.15

Though African Americans had a presence in the RNC and state parties in the 1920s, the decade’s three Republican presidents did little to ease a growing frustration among rank-and-file black voters. Presidents Harding and Calvin Coolidge failed to reverse the policies of their Democratic predecessor, Woodrow Wilson, that segregated federal departments. Coolidge, one of the most hands-off presidents in U.S. history, could barely even denounce lynching or the Ku Klux Klan, let alone actively pursue a civil rights agenda. Most notably, despite Republican control of both houses of Congress and the White House throughout the decade, the party failed to pass a promised anti-lynching law. By the end of the decade, black voters in the North had already begun the process of realignment toward more sympathetic Democratic politicians.16

The national Democratic Party, however, was not a welcoming alternative, as it still had a large southern bloc and made few efforts to court African Americans. There were no black delegates at the 1928 Democratic National Convention in Houston, and black attendants were segregated behind humiliating chicken wire. By contrast, forty-nine black delegates attended the Republican convention in Kansas City, though the party’s nominee was not much of an improvement over his lackluster predecessors. Herbert Hoover, a former U.S. secretary of commerce with few black contacts in his home state of ...