![]()

SCIENTIFIC DEDUCTIONS

and CONJECTURES

CAUSE OF COLDS

TO

BENJAMIN RUSH

London, July 14, 1773.

DEAR SIR,

I SHALL communicate your judicious remark, relating to the septic quality of the air transpired by patients in putrid diseases, to my friend Dr. Priestley. I hope that after having discovered the benefit of fresh and cool air applied to the sick, people will begin to suspect that possibly it may do no harm to the well. I have not seen Dr. Cullen’s book, but am glad to hear that he speaks of catarrhs or colds by contagion. I have long been satisfied from observation, that besides the general colds now termed influenzas, (which may possibly spread by contagion, as well as by a particular quality of the air), people often catch cold from one another when shut up together in close rooms, coaches, &c., and when sitting near and conversing so as to breathe in each other’s transpiration; the disorder being in a certain state. I think, too, that it is the frouzy, corrupt air from animal substances, and the perspired matter from our bodies, which being long confined in beds not lately used, and clothes not lately worn, and books long shut up in close rooms, obtains that kind of putridity, which occasions the colds observed upon sleeping in, wearing, and turning over such bedclothes, or books, and not their coldness or dampness. From these causes, but more from too full living, with too little exercise, proceed in my opinion most of the disorders, which for about one hundred and fifty years past the English have called colds.

As to Dr. Cullen’s cold or catarrh a frigore, I question whether such an one ever existed. Travelling in our severe winters, I have suffered cold sometimes to an extremity only short of freezing, but this did not make me catch cold. And, for moisture, I have been in the river every evening two or three hours for a fortnight together, when one would suppose I might imbibe enough of it to take cold if humidity could give it; but no such effect ever followed. Boys never get cold by swimming. Nor are people at sea, or who live at Bermudas, or St. Helena, small islands, where the air must be ever moist from the dashing and breaking of waves against their rocks on all sides, more subject to colds than those who inhabit part of a continent where the air is driest. Dampness may indeed assist in producing putridity and those miasmata which infect us with the disorder we call a cold; but of itself can never by a little addition of moisture hurt a body filled with watery fluids from head to foot.

With great esteem, and sincere wishes for your welfare, I am, Sir,

Your most obedient humble servant,

B. FRANKLIN.

DEFINITION of a COLD

IT is a siziness and thickness of the blood, whereby the smaller vessels are obstructed, and the perspirable matter retained, which being retained offends both by its quantity and quality; by quantity, as it overfills the vessels, and by its quality, as part of it is acrid, and being retained, produces coughs and sneezing by irritation.

HEAT AND COLD

TO

JOHN LINING

at Charleston, South Carolina

New York, April 14, 1757.

SIR,

PROFESSOR SIMSON, of Glasgow, lately communicated to me some curious experiments of a physician of his acquaintance, by which it appeared that an extraordinary degree of cold, even to freezing, might be produced by evaporation. I have not had leisure to repeat and examine more than the first and easiest of them, viz. Wet the ball of a thermometer by a feather dipped in spirit of wine, which has been kept in the same room, and has, of course, the same degree of heat or cold. The mercury sinks presently three or four degrees, and the quicker, if, during the evaporation, you blow on the ball with bellows; a second wetting and blowing, when the mercury is down, carries it yet lower. I think I did not get it lower than five or six degrees from where it naturally stood, which was, at that time, sixty. But it is said, that a vessel of water being placed in another somewhat larger, containing spirit, in such a manner that the vessel of water is surrounded with the spirit, and both placed under the receiver of an air-pump; on exhausting the air, the spirit, evaporating, leaves such a degree of cold as to freeze the water, though the thermometer, in the open air, stands many degrees above the freezing point.

I know not how this phenomenon is to be accounted for; but it gives me occasion to mention some loose notions relating to heat and cold, which I have for some time entertained, but not yet reduced into any form. Allowing common fire, as well as electrical, to be a fluid capable of permeating other bodies, and seeking an equilibrium, I imagine some bodies are better fitted by nature to be conductors of that fluid than others; and that, generally, those which are the best conductors of the electrical fluid, are also the best conductors of this; and e contra.

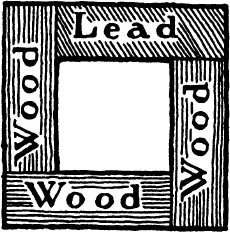

Thus a body which is a good conductor of fire readily receives it into its substance, and conducts it through the whole to all the parts, as metals and water do; and if two bodies, both good conductors, one heated, the other in its common state, are brought into contact with each other, the body which has most fire readily communicates of it to that which had least, and that which had least readily receives it, till an equilibrium is produced. Thus, if you take a dollar between your fingers with one hand, and a piece of wood, of the same dimensions, with the other, and bring both at the same time to the flame of a candle, you will find yourself obliged to drop the dollar before you drop the wood, because it conducts the heat of the candle sooner to your flesh. Thus, if a silver tea-pot had a handle of the same metal, it would conduct the heat from the water to the hand, and become too hot to be used; we therefore give to a metal teapot a handle of wood, which is not so good a conductor as metal. But a china or stone tea-pot being in some degree of the nature of glass, which is not a good conductor of heat, may have a handle of the same stuff. Thus, also, a damp moist air shall make a man more sensible of cold, or chill him more, than a dry air that is colder, because a moist air is fitter to receive and conduct away the heat of his body. This fluid, entering bodies in great quantity first expands them by separating their parts a little, afterwards, by farther separating their parts, it renders solids fluid, and at length dissipates their parts in air. Take this fluid from melted lead, or from water, the parts cohere again; (the first grows solid, the latter becomes ice;) and this is sooner done by the means of good conductors. Thus, if you take, as I have done, a square bar of lead, four inches long, and one inch thick, together with three pieces of wood planed to the same dimensions, and lay them, as in the margin, on a smooth board, fixed so as not to be easily separated or moved, and pour into the cavity they form, as much melted lead as will fill it, you will see the melted lead chill, and become firm, on the side next the leaden bar, some time before it chills on the other three sides in contact with the wooden bars, though, before the lead was poured in, they might all be supposed to have the same degree of heat or coldness, as they had been exposed in the same room to the same air. You will likewise observe, that the leaden bar, as it has cooled the melted lead more than the wooden bars have done, so it is itself more heated by the melted lead. There is a certain quantity of this fluid, called fire, in every living human body, which fluid, being in due proportion, keeps the parts of the flesh and blood at such a just distance from each other, as that the flesh and nerves are supple, and the blood fit for circulation. If part of this due proportion of fire be conducted away, by means of a contact with other bodies, as air, water, or metals, the parts of our skin and flesh that come into such contact first draw more near together than is agreeable, and give that sensation which we call cold; and if too much be conveyed away, the body stiffens, the blood ceases to flow, and death ensues. On the other hand, if too much of this fluid be communicated to the flesh, the parts are separated too far, and pain ensues, as when they are separated by a pin or lancet. The sensation, that the separation by fire occasions, we call heat, or burning. My desk on which I now write, and the lock of my desk, are both exposed to the same temperature of the air, and have therefore the same degree of heat or cold; yet if I lay my hand successively on the wood and on the metal, the latter feels much the coldest, not that it is really so, but, being a better conductor, it more readily than the wood takes away and draws into itself the fire that was in my skin. Accordingly if I lay one hand, part on the lock, and part on the wood, and, after it has lain so some time, I feel both parts with my other hand, I find that part that has been in contact with the lock, very sensibly colder to the touch, than the part that lay on the wood. How a living animal obtains its quantity of this fluid, called fire, is a curious question. I have shewn, that some bodies (as metals) have a power of attracting it stronger than others; and I have sometimes suspected, that a living body had some power of attracting out of the air, or other bodies, the heat it wanted. Thus metals hammered, or repeatedly bent grow hot in the bent or hammer’d part. But when I consider that air, in contact with the body, cools it; that the surrounding air is rather heated by its contact with the body; that every breath of cooler air, drawn in, carries off part of the body’s heat when it passes out again; that therefore there must be some fund in the body for producing it, or otherwise the animal would soon grow cold; I have been rather inclined to think, that the fluid fire, as well as the fluid air, is attracted by plants in their growth, and becomes consolidated with the other materials of which they are formed, and makes a great part of their substance. That, when they come to be digested, and to suffer in the vessels a kind of fermentation, part of the fire, as well as part of the air, recovers its fluid, active state again, and diffuses itself in the body digesting and separating it. That the fire, so reproduced by digestion and separation, continually leaving the body, its place is supplied by fresh quantities, arising from the continual separation. That whatever quickens the motion of the fluids in an animal quickens the separation, and reproduces more of the fire, as exercise. That all the fire emitted by wood and other combustibles when burning existed in them before in a solid state, being only discover’d when separating. That some fossils, as sulphur, sea-coal, &c., contain a great deal of solid fire. And that in short, what escapes and is dissipated in the burning of bodies, besides water and earth, is generally the air and fire that before made parts of the solid. Thus I imagine, that animal heat arises by or from a kind of fermentation in the juices of the body, in the same manner as heat arises in the liquors preparing for distillation, wherein there is a separation of the spirituous, from the watery and earthy parts. And it is remarkable, that the liquor in a distiller’s vat, when in its highest and best state of fermentation, as I have been inform’d, has the same degree of heat with the human body, that is about 94 or 96.

Thus, as by a constant supply of fuel in a chimney, you keep a warm room, so, by a constant supply of food in the stomach, you keep a warm body; only where little exercise is used, the heat may possibly be conducted away too fast; in which case such materials are to be used for cloathing and bedding, against the effects of an immediate contact of the air, as are, in themselves, bad conductors of heat, and, consequently prevent its being communicated thro’ their substances to the air. Hence what is called warmth in wool, and its preference, on that account, to linnen; wool not being so good a conductor. And hence all the natural coverings of animals, to keep them warm, are such as retain and confine the natural heat in the body by being bad conductors, such as wool, hair, feathers, and the silk by which the silk-worm, in its tender embrio state, is first cloathed. Cloathing thus considered does not make a man warm by giving warmth, but by preventing the too quick dissipation of the heat produced in his body, and so occasioning an accumulation.

There is another curious question I will just venture to touch upon, viz. Whence arises the sudden extraordinary degree of cold, perceptible on mixing some chymical liquors, and even on mixing salt and snow, where the composition appears colder than the coldest of the ingredients? I have never seen the chymical mixtures made; but salt and snow I have often mixed myself, and am fully satisfied that the composition feels much colder to the touch, and lowers the mercury in the thermometer more, than either ingredient would do separately. I suppose, with others, that cold is nothing more than the absence of heat or fire. Now if the quantity of fire before contained or diffused in the snow and salt was expell’d in the uniting of the two matters, it must be driven away either thro’ the air or the vessel containing them. If it is driven off thro’ the air, it must warm the air; and a thermometer held over the mixture, without touching it, would discover the heat, by the rising of the mercury, as it must, and always does, in warmer air.

This indeed I have not try’d but I should guess it would rather be driven off thro’ the vessel, especially if the vessel be metal, as being a better conductor than air, and so one should find the bason warmer after such mixture. But on the contrary the vessel grows cold, and even water, in which the vessel is sometimes placed for the experiment, freezes into hard ice on the bason. Now I know not how to account for this, otherwise than by supposing, that the composition is a better conductor of fire than the ingredients separately and like the lock ...