![]()

PART I

Children

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Christian Schools

The September 1962 issue of Christian School Guide sounded warning bells about the recent Supreme Court decision in Engel v. Vitale, which prohibited public schools in New York from opening the school day with a mandatory prayer. “With the removal of God from the classroom,” blared the magazine’s front-page story, “They have taken away My Lord.” The magazine’s editor, Chicago-based school administrator Mark Fakkema, reported that an investigation had “revealed that at the beginning of our nation (1776) study materials used in schools were 100% Christian. In 1850 they were 50% Christian.” In 1962, however, “government schools” were almost devoid of Christian influence. To be sure, thousands of public schools ignored the Engel decision for years. But the die was cast. God had been kicked out of the public school classroom. Evangelical Christians could not afford to leave their kids in it.1

Fakkema’s decision to spotlight the Engel decision presaged five decades of evangelicals’ anxiety over the fate of religion in public schools. In 1962, when the Court handed down the decision, a vast majority of conservative Protestants enrolled their children in public schools. Private religious schools in the United States were overwhelmingly parochial schools, most of them Catholic or Lutheran. The Engel decision, coupled with the court’s decision to outlaw devotional Bible reading in public schools via the 1963 case Abingdon v. Schempp, helped change that. Those two decisions convinced increasing numbers of conservative Protestants that public schools had forsaken their religious roots and now aimed to indoctrinate children with humanism.

In response, evangelicals began building private schools at a breathtaking pace. Between 1970 and 1980, enrollment in non-Catholic, church-related schools increased 137 percent, from 561,000 to 1,329,000.2 The fast growth continued into the 1980s: the Association of Christian Schools, International reported nearly 1,000 new member schools between 1980 and 1985 (a 66% increase).3 While older private schools (mainly parochial schools and college preparatory academies) experienced moderate expansion during this two-decade explosion of private school growth, most of the increase occurred in new academies launched by conservative evangelicals. In fact, Catholic schools were closing at alarming rates during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Catholic schools educated over 10% of school-aged children in the mid-1960s, but as white Catholics fled cities for the suburbs, hundreds of parochial schools closed. Since Catholic schools had become so integral to American education, state and federal officials worried about their decline and experimented with voucher systems that provided funds to parents who sent their children to private schools. But the shuttering of Catholic schools continued. Evangelicals, meanwhile, built up their educational empires—both K-12 schools and colleges—in the growing suburbs. By the early 1980s, preachers like Jerry Falwell and Tim LaHaye claimed that evangelicals were opening three new private schools every day.4

Examining the dramatic growth of Christian schools provides a compelling place to study the origins of the family values movement. Other studies of the Christian right begin with the mid-century evangelism of Billy Graham, the 1970s campaign against the Equal Rights Amendment, or evangelicals’ loud protests against abortion and gay rights in the 1980s and 1990s.5 All those stories are important. But Christian academies stand out for a couple reasons. First, leaders of these schools disseminated a vision of social order that spotlighted the role of the family and the importance of authority. Conservative Protestants rejected the 1960s mantra “question authority.” They believed that external authority was essential to social order. Specifically, conservative Christians argued that God—the ultimate authority—had ordained only two human institutions: the family and the church. Christian school proponents felt that public schools denigrated the family and ignored the church. Conversely, Christian academies viewed themselves as both “a reinforcement of the Christian home” and as an extension of the local church; they were often literal extensions of the church’s building.6 Private academies thereby served as visible manifestations of the social order conservatives thought essential. These schools provided a refuge for family values.

Second, the rapid growth of Christian schools encouraged the building of national networks of conservative evangelical ministers, school administrators, and parents. Parents who pulled their kids out of public schools did not necessarily know how to run schools themselves. They relied on literature and periodicals from groups like the Association of Christian Schools, International (ACSI), American Association of Christian Schools (AACS), and National Association of Christian Schools (NACS) to set up and sustain their fledgling academies. The National Association of Evangelicals launched the NACS in 1947, and it published materials designed to help Protestants launch Christian academies from its headquarters in Wheaton, Illinois. In the 1970s, the AACS, based in Tennessee, and ACSI, based first in California and later in Colorado, emerged and quickly became the two largest Christian school organizations in the country. By the mid-1980s, AACS and ACSI claimed 2,808 member schools.7 Though that number reflected only a fraction of the myriad Christian schools dotting the American landscape, AACS and ACSI membership became increasingly important to schools whose student body drew from constituencies beyond the congregation of the sponsoring church. These organizations began by filling an immediate need: helping ministers and parents figure out how to open and operate a Christian school. They published pamphlets listing curricular resources and local contacts for Christian school administrators.

While these national organizations provided basic instructions for launching Christian academies, AACS and ACSI newsletters and curricula also disseminated a political vision that gave Christian school devotees a common language for addressing the plight of the nation. Recall Fakkema’s description of public schools: what had once been “100% Christian,” in the minds of evangelicals, had become the province of humanism. Private Christian academies became the first line of defense against the secularization of the next generation. Christian school organizations helped connect men and women concerned about the plight of education and set the table for future battles over the soul of America.

Christian Schools and Desegregation

The expansion of Christian schools coincided with desegregation of public schools in the South, and although scores of Christian academies cropped up in the Midwest and in the Southwest, the rate of expansion among Christian schools was highest in the South.8 Two Supreme Court decisions—Green v County School Board of New Kent County (1968) and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971)—built on the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision mandating desegregation of public schools. In Green, the Court ruled that southern school systems could no longer justify segregation by pointing to difficulties in implementing full integration plans. The Court ordered school systems to take necessary measures in order to desegregate immediately. Three years later, Swann affirmed cross-town busing as a legitimate means to ensure desegregation in the public schools. The latter decision, especially, struck a nerve with parents, many of whom resented busing even if they were generally amenable to school desegregation. Christian schools found themselves the beneficiaries of parents’ frustration. “I am revolting against busing,” said one when asked why she enrolled her child in private school. A school administrator admitted, “the busing order gave us five to ten years of growth compressed into one year.”9 These comments revealed the ways the Supreme Court inadvertently spurred Christian school growth.10

Moreover, while many Christian academies allowed for token integration in the early 1970s, whites constituted the vast majority of students. Paul F. Parsons, a journalist who studied Christian schools in the mid-1980s, estimated that minorities constituted less than 3 percent of the student population in the vast majority of Christian schools. Only about 10 percent of Christian schools featured student bodies with 10 percent or more minority enrollment. Although some administrators told Parsons, “we want blacks in the school,” African Americans showed little inclination to send their children to Christian schools. Some black parents cited financial obstacles to enrolling their children; others perceived the schools as white flight academies.11 Furthermore, private Christian schools rejected some public school reforms that appealed to African Americans. For instance, public school emphasis on multiculturalism found little favor in the Christian academy movement, which privileged older textbooks filled with “traditional values”—and few minority authors.

The makeup of Christian school leadership also demonstrated whites’ control over the movement. In 1987, the executive board for the Association of Christian Schools International included 28 white males, one white female—and no minorities.12 As one historian put it, “Academy supporters wanted to create a world where racial tensions did not exist, so they built schools where racial differences had no place.”13 In other words, the schools’ professed desire for increasing diversity did not mean they went the extra mile to recruit black students or make their academies friendly to skeptical African Americans.

Yet to say the schools benefited from resistance to public school desegregation does not exclude other rationales for Christian education—nor does it account for schools that emerged in regions where desegregation was not seen as threatening. One historian has suggested that we divide private institutions into “segregation academies,” which were public in all but name and existed solely to perpetuate segregation during the late 1960s, and “church schools,” which emerged in the 1970s to combat perceived secularism in the public schools. These categories prevent historians from lumping all private schools into a single category.14 Plenty of Christian schools emerged during the 1970s for a complex assortment of reasons, which included avoiding desegregation and combating secularism.

Take, for instance, Lynchburg Christian Academy (LCA), a private school launched by the Reverend Jerry Falwell, who would later become the most visible member of the Christian right. Opened in 1967, the same year Lynchburg public schools desegregated, LCA immediately faced the wrath of a group of liberal clergy, who charged the school with racism. They published an ad saying, “We [who are] sensitive to Our Lord’s inclusiveness … deplore the use of the term ‘Christian’ in connection with private schools which exclude Negroes and other non-whites.”15 Falwell later maintained that the school never had a “whites only” policy, but the Lynchburg News described the school as “a private school for white students,” a designation neither Falwell nor the school challenged at the time.16 Falwell himself had preached at least two sermons against the civil rights movement in 1964 and 1965. Demonstrators from the Congress on Racial Equality had protested at Falwell’s church, and black members were not permitted until 1968.17 In the context of Falwell’s record on civil rights during the 1960s—and given the timing of the school’s opening—it is difficult to see Lynchburg Christian Academy as anything but a segregation academy.

Yet LCA would need to find new ways to maintain its existence after the first few years of public school desegregation. In the late 1960s African Americans made up only 19.5 percent of Lynchburg’s population, the second-lowest proportion among Virginia cities.18 By the late 1960s white southerners in most communities had learned how to desegregate in ways that did not threaten their control over the schools.19 In cities like Lynchburg, white control over public schools meant that desegregation proceeded in ways that guaranteed minimal disruption to white communities and schools. (Busing, of course, would have changed this reality, but Lynchburg did not have a court-mandated busing program in 1967.) In cities where whites could not achieve numerical dominance in public schools, private schools—segregation academies—proliferated. A study of school desegregation in Mississippi, for instance, found that the emergence of all-white private schools “was more closely related to the black percentage of population within the school district’s boundaries than to any other factor.”20 Lynchburg, with its relatively low proportion of African Americans was, if nothing else, demographically atypical among cities featuring segregation academies. The timing of LCA’s emergence was not coincidental; school founders knew public school desegregation would cause some white parents to send their children to private schools. But as desegregation proceeded, and whites maintained majority control over public schools, LCA would need other rationales to sustain its enrollment.

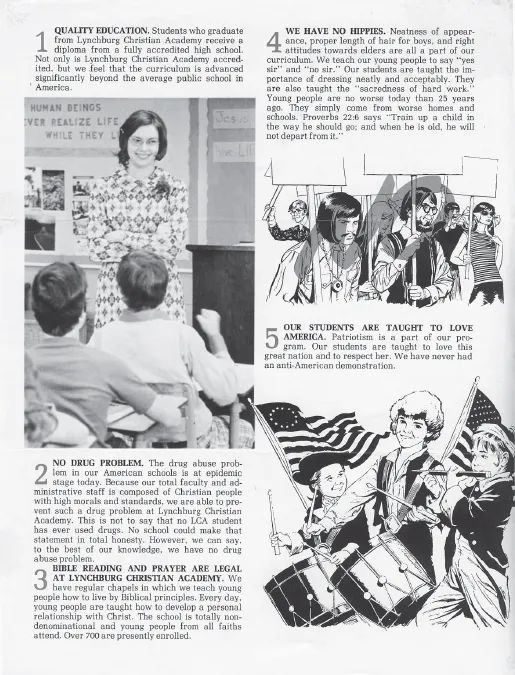

LCA’s early promotional materials provided a glimpse of how the school would market itself. A pamphlet called “Five Things We Think You Will Like About Lynchburg Christian Academy” ticked off the main advantages of religious schooling: quality education, no drug problem, legal Bible reading and prayer, no hippies, and the teaching of patriotism. The pamphlet featured an energetic fife and drum corps comprised of patriotic-looking young men and contrasted it with a sullen group of hippie protesters. A smiling teacher, backed by religious messages on a bulletin board, presided over a class of attentive students. The message was obvious: LCA provided a haven from the degeneracy that marked the hippie generation. It promoted a love of country and a respect for authority.21

LCA also promoted family values. Thomas Road Baptist Church (TRBC), which sponsored the school, asked all faculty and staff to attend a “Family Seminar” at the church. The director of the Family Services Department at TRBC, Al Kinchen, spoke at a parent-teacher fellowship meeting in 1972. Topics covered included “overcoming a condemning attitude, gaining victory over impure thoughts, qualities for developing a successful marriage, how to follow God’s chain of command in marriage, [and] how to teach a child to stand alone on the side of right.”22 The school responded to the threat of a culture that questioned authority by underlining both the importance of the family and the lines of authority within it.

LCA concern for family values demands attention to the ways academy leaders and parents depicted the role of Christian academies. The school benefited from backlash toward public school desegregation, and it did not admit even a single minority student in its first two years. But looking at it solely as a segregation academy obscures the complex factors that fueled its success. By the mid-1970s, LCA enrolled a small proportion of minority students, lessening the difference between its racial composition and that of the city’s public schools. Parents who sent their children there responded to the school’s nostalgic appeal to an “old-fashioned” environment and curriculum. This appeal worked brilliantly. In the early 1970s LCA moved from cramped Sunday school rooms to a new facility and earned accreditation. By 1972 an initial enrollment of 105 students had swelled to 684. And in 1971 Falwell opened a liberal arts college—now known as Liberty University—to augment his educational empire. At the end of the twentieth century, Liberty enrolled a higher proportion of African American students than any other Virginia university, save for historically black colleges. If the school’s origins lay in the fallout from public school desegregation, its subsequent development depended on other factors.

Figure 1. This 1975 advertisement for Lynchburg Christian Academy listed “five things we think you will like” about the school. Image courtesy of Liberty Christian Academy.

The segregationist origins of countless private Christian academies have obscured a commitment among school proponents to proper order. The ministers and parents who enrolled their children in Christian schools had an ugly record on civil rights, which they camouflaged in the 1970s and apologized for in the 1980s and 1990s. It would be easy, then, to dismiss these schools as bastions of racism. But a better understanding of the unde...