![]()

APPENDIX 1

Life and Adventures of Charles Anderson Chester

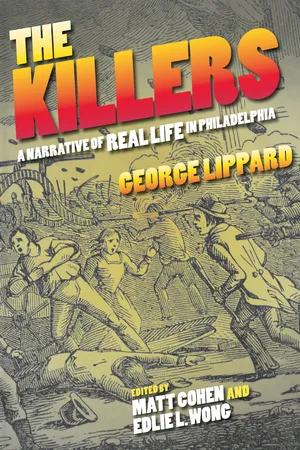

FIGURE 8. “A cry at once arose that a white man was shot.”

George Lippard, Life and Adventures of Charles Anderson Chester

(Philadelphia: Yates and Smith, 1849/50), frontispiece. Am 1850 Lif 76423.O.

Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

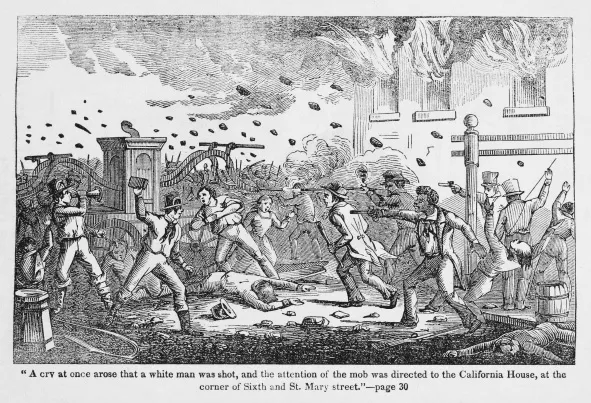

FIGURE 9. Title page.

George Lippard, Life and Adventures of Charles Anderson Chester

(Philadelphia: Yates and Smith, 1849/50). Am 1850 Lif 76423.P.

Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Entered according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1849,

BY YATES & SMITH

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

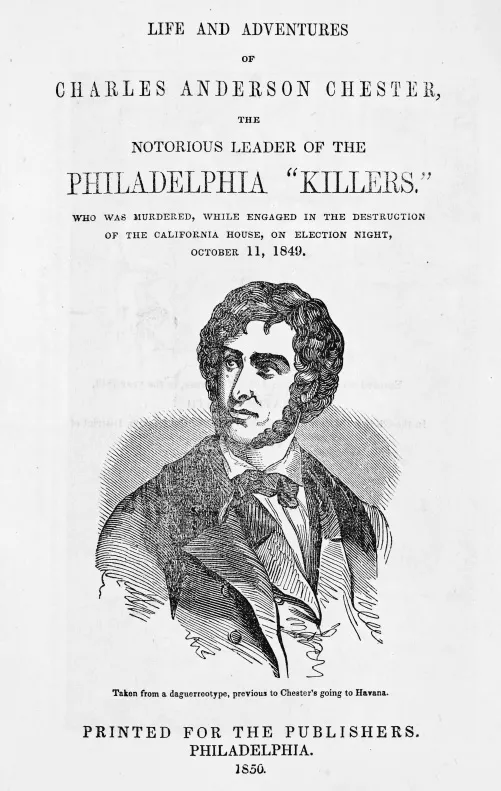

FIGURE 10. “Charles Anderson Chester Murdered by Black Herkles.”

George Lippard, Life and Adventures of Charles Anderson Chester

(Philadelphia: Yates and Smith, 1849/50), p. 9. Am 1850 Lif 76423.O.

Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

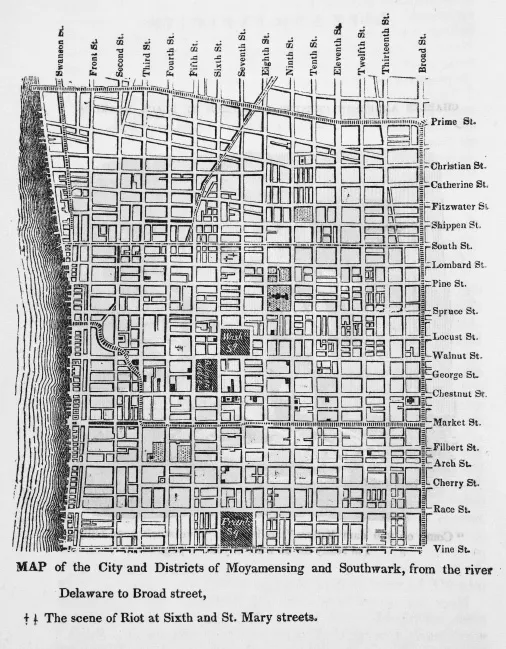

FIGURE 11. “MAP of the City and Districts of Moyamensing and Southwark.” The map appears here as originally printed, its orientation inverted from the customary one, with north at the bottom.

George Lippard, Life and Adventures of Charles Anderson Chester

(Philadelphia: Yates and Smith, 1849/50), p. 10. Am 1850 Lif 76423.O.

Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

THE

LIFE AND EXPLOITS

OF

CHARLES ANDERSON CHESTER.

CHAPTER I.

Charles Anderson Chester—His youth and parentage—Adventures at College—Letter from his Father—Flight from College.

CHARLES ANDERSON CHESTER, the subject of this eventful narrative, was the son of a wealthy, and as the world goes, a respectable parentage. His father was at once a Merchant and a Banker; and his mother was the daughter of a millionaire. Accustomed from his earliest years to all that wealth can offer, to pamper the appetite and deprave the passions, Anderson grew to manhood with a great sense of his own importance derived from the wealth of his father. He was sent at the age of eighteen, from the roof of his father’s splendid mansion, to a New England College, “to complete his education.” His education supposed to have been commenced at the University of Pennsylvania, had in reality begun at the Hunting Park Race Course, at the Chesnut Street gambling hell, the Theatre and the Brothel. At eighteen he was already known as a “man about town.” He drove the handsomest turn out on Broad Street; he played “Brag,”1 with the oldest gamesters, and drank his four bottles of Champaigne with the most experienced of veteran drunkards. And thus initiated into life, he went to New England to finish his education.

Here his career was short and brilliant. He flogged his tutor, attempted to set fire to the College buildings and was very nearly successful in an attempt to abduct the only daughter of the President. These, with numerous minor exploits produced his expulsion after a brief period of six months.

At this state of affairs Anderson knew not what to do. He did not like the idea of returning home. His father was a bon vivant,—a good liver of the canvass back order,—liberal at times,—but again as obstinate as the pride of money, and the habit of commanding men’s lives with the power of money, could make him. He was withal a nominal member of a wealthy Church. He might possibly wink at Anderson’s Collegiate exploits, and term them the effusions of a “spirited nature” winding up with a check for a $1000, or he might bid his son to go to sea, to list in the army, or go to a place not mentioned to ears polite. What would be his course? Anderson could not tell.

He was sitting in his room, at the crack hotel of the College town, when he received his father’s letter. He had spent his last dollar. He was in arrears for board. He was beset by duns, duns of every shape from the waiter to the washer-woman. While meditating over the state of affairs he received his father’s letter. It was terse and to the point.

SIR:—You have made your bed and you must lie down in it. Expect nothing from me. You can choose your own course. At the same time, you will distinctly understand, that by your conduct you have cast off all claims upon your family, who desire to hear nothing from you until you are sincerly repentent for the disgrace which your behaviour has heaped upon them.

JACOB CHESTER.

This was not a very fatherly letter it must be confessed, though the conduct of Anderson had been bad enough. He read it over and over again—held it near the light until the glare played over his face, corrugated by silent rage,—and after a few moments consigned it to his vest pocket.

All was still in the hotel. He at once determined upon his plan. Dressing himself in a green walking coat trimmed with metal buttons, plaid pants and buff vest, Anderson walked quietly from his room, and as quietly left the hotel at the dead hour of the night. He left without “bag or baggage,” and striking over the fields, through a driving mist, he made his way to a railway station distant some five miles. The passions of a demon were working in his heart, for the manner in which his father had winked at his early faults, only served to render his letter more intolerable and galling.

How he obtained passage in the cars we cannot tell. Suffice it to say, that after two days he landed in Philadelphia, his apparel dusty and way-worn, and his shirt collar hidden ominously behind the folds of his black cravat.

He was tall for his age. His chin already was darkened by a beard that would not have shamed a Turk. Light complexioned and fair haired, he was the very figure to strike the eye on Chesnut street, or amid the buz and uproar of a ball.

Dusty, tired and hungry, he made the best of his way to his father’s mansion. He was determined to have an interview with the old man. Stepping up the marble stair case, he rung the bell, and stood for a few moments with a fluttering heart. A strange servant answered the bell, and greeted him with the news, “that Mr. Chester and his family had left for Cape May the week before.”

This was bad news for Anderson. Turning from his father’s house, he sauntered listlessly toward the Exchange,2 until he came near his father’s store,—a dark old brick building, standing sullen and gloomy amid fashionable dwellings of modern construction. He entered the counting room. It was situated at the farther end of a large gloomy place, and was fenced off from bales of goods, and hogsheads of cogniac, by a dingy railing of unpainted pine.

CHAPTER II.

Mr. Smick the head clerk—The check for $5,000—Charles contrives a scheme—Its result—Interview with a certain personage which has an important bearing on his fate—The British Captain.

“WHERE is Mr. Smick?” asked Anderson of the negro porter, who was the only person visible.

“Jist gone out,” answered the porter, who did not recognize his employer’s son, “Back d’rectly.

“I’ll wait for him,” was the answer, and Anderson sauntered into the counting room, which was furnished with an old chair, a large desk and range of shelves filled with ledgers, etc.

An opened letter, spread upon the desk, attracted the eye of the hopeful youth. It was from Cape May, bore the signature of his father, was addressed to Mr. Smick his head clerk, and contained this brief injuntion.—3

“Smick—I send you a check for $5,000. Cash it, and meet that note of Johns & Brother—to-morrow—you understand.”

“Where the deuce is the check?” soliloquized Anderson, and forthwith began to search for it, but in vain. While thus engaged his ear was attracted by the sound of a footstep. Looking through the railing he beheld a short little man with a round face and a hooked nose, approaching at a brisk pace. As he saw him, his fertile mind, hit upon a plan of operations.

“Smick my good fellow,” he said as the head clerk opened the door of the counting-room—“I’ve been looking for you all over town. Quick! At Walnut street wharf! There’s no time to be lost!”

He spoke these incoherent words with every manifestation of alarm and terror. As much surprised at the sudden appearance of the vagabond son in the counting room, as at his hurried words, the head clerk was for a few moments at a loss for words.

“You here—umph! Thought you was at college—eh!” exclaimed Smick as soon as he found his tongue—“Walnut street wharf! What do you mean?”

“Mr. Smick,” responded the young man slowly and with deliberation, “I mean that on returning from Cape May father has been stricken with an apopletic fit. He’s on board of the boat. Mother sent me up here, to tell you to come down without delay. Quick! No time’s to be lost.”

Smick seemed thunderstricken. He placed his finger on the tip of his nose, muttering “Chester struck with apoplexy—bad, bad! Here’s this check to be cashed, and that note of Johns & Brother to be met. What shall I do—”

“I’ll tell you Smick. Give me the check—I’ll get it cashed and then go and take up the note, while you hurry down to the wharf.”

He said this in quite a confidential manner, laying his hand on Smick’s arm and looking very knowingly into his face.

In answer to this, Mr. Smick closed one eye—arranged his white cravat—and seemed buried in thought, while Charles stood waiting with evident impatience for his answer.

“You’ve been to Cape May—have you?” he said, regarding Charles with one eye closed.

“You know I have not. I have just got on from New York, and met one of father’s servants, as I was coming off the boat. He told me the old gentleman had been taken with apoplexy on the way up. I went into the cabin of the Cape May boat which had just come to, and saw father there. Mother gave me the message which I have just delivered. Indeed, Mr. Smick you’d better hurry.”

“Then you had better take the check,” said Smick extending his hand. “Get it cashed and take up that note. It is now half past two, it must be done without delay.”

His eyes glistening Charles reached forth his hand to grasp the check, when Mr. Smick drew back his hand, quietly observing at the same time “I think Charles you had better ask your father. Here he is. Rather singular that he’s so soon recovered from his fit of apoplexy!”

Scarcely had the words passed his lips, when at his shoulder, appeared the portly figure of the father,—Mr. Jacob Chester, a gentleman of some fifty years, dressed in black with a white waistcoat. His ruddy face was overspread with a scowl; he regarded his son with a glance full of meaning, at the same time passing his kerchief incessantly over his bald crown. He had overheard the whole of the conversation between his son and his head clerk. He had indeed returned from Cape May, but had seen his clerk, only five minutes previous to this interview. His feelings as he overheard the conversation may be imagined.

“Scoundrel!” was his solitary ejaculation, as he gazed upon his son, who now stood cowering and abashed, in one corner of the counting room.

“Father—” hesitated Charles.

The merchant pointed to the door.

“Go!” he said, and motioned with his finger.

“Forgive me father,—I’ve been wild. I know it,” faltered Charles.

“You saw me in a fit, did you? And you would have got that check cashed and taken up Johns’ note, would you? You’re a bigger scoundrel than I took you for. Go!”

Charles moved to the door. While Smick stood thunderstricken, the father followed his son into the large room, which, filled with hogsheads and bales, intervened between the countingroom and the street. Charles quietly threaded his way through the gloomy place, and was passing to the street when his father’s hand stopped him on the threshold.

“Charles,” said he, “let us understand one another.”

Charles turned with surprise pictured on his face; the countenance of his father was fraught with a meaning which he could not analyze.

“In the first place,” said the Merchant, “read this.”

He handed his son a copy of the New York Herald, dated the day previous. The finger of Mr. Jacob Chester pointed a paragra...