![]()

Part II

RETURNING URBAN PLACES TO ECONOMIC VIABILITY

![]()

CHAPTER 6

Measuring Katrina’s Impact on the Gulf Megapolitan Area

Robert E. Lang

“Houston, too close to New Orleans,” sang the Grateful Dead in their popular song “Truckin” back in the 1970s. Although written decades ago, these lyrics nicely capture the relationship between the two big cities of the Gulf Coast. While Houston and New Orleans may not be close enough to form a Dallas/Fort Worth-style “metroplex,” they nonetheless anchor an extended Gulf Coast “megapolitan corridor” that stretches from Pensacola, Florida, in the east, to greater Houston in the west.1 Houston, it turns out, is very close to New Orleans. The region played a key role in the Crescent City’s immediate recovery from Hurricane Katrina, taking on the shipping traffic and energy business from its neighbor and providing a safe haven for the displaced.

The nation’s southernmost transcontinental Interstate, I-10, serves as the Gulf Coast’s “Main Street.” Every major city in the megapolitan area lies along its path. Katrina, and to a lesser extent Hurricane Rita, sliced through the heart of the I-10 urban corridor. The hurricanes tore up ports, disabled refineries, and flooded large sections of the coast including much of New Orleans. The immediate national impact was an energy spike that demonstrated the Gulf Coast’s critical role in oil and gas production.

This essay looks at the impact that Hurricanes Katrina had on New Orleans and the Gulf Coast Megapolitan Area. It addresses the nature of how this region is economically and environmentally integrated. It also explores how resilient the Gulf Coast will prove in the coming years. The fact that New Orleans links to a megapolitan urban network has already helped to manage the disaster. The larger Gulf Coast absorbed most of the city’s displaced. The Houston and Baton Rouge metropolitan areas in particular gained both people and commerce due to Katrina. Fortunately, Hurricane Rita missed metropolitan Houston. Had it struck the region with the same intensity as Katrina did New Orleans, the Gulf Coast’s two anchor metros would have been damaged at the same moment, rendering both unable to assist the other.

WHAT IS A MEGAPOLITAN?

Megapolitan Areas are integrated networks of metropolitan and micropolitan areas. The name Megapolitan plays off Jean Gottmann’s (1961) “megalopolis” label by using the same prefix—“mega.” According to an analysis by the Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech (Lang, Nelson, and Dhavale 2006), the U.S. has eleven “Megas” (see Figure 1), with six in the eastern half of the U.S. and five in the west. Megapolitan Areas extend into thirty-seven states, including every one east of the Mississippi River except Vermont. As of 2004, Megapolitan Areas contained about a fifth of all land area in the lower forty-eight states, but captured almost 70% of the total U.S. population with more than 210 million people. The sixteen most populous U.S. metropolitan areas are also found in Megas.

By 2040, Megapolitan Areas are projected to gain over eighty-five million residents, or about three-quarters of national growth (Lang, Nelson, and Dhavale 2006). To put this in perspective, consider that this area, which is smaller than northwest Europe, is about to add a population exceeding that of Germany by mid-century. The costs of building the residential dwellings and commercial facilities to accommodate this growth could run over $35 trillion by some estimates (Nelson 2004).

A direct functional relationship as indicated by commuting only tenuously exists at the megapolitan scale. The area is simply too big to make many daily trips possible between distant sections. However, data showing “stretch commutes” of 50 and 100 miles each way indicate a growing number of people who journey for work between megapolitan metros (Lang, Nelson, and Dhavale 2006).

The changing nature of work is also feeding this transformation. In many fields workers simply need not be present in the office five days per week. The practice of “hoteling,” where employees “visit” work infrequently and mostly work at home or on the road is common in high tech firms and will soon spread to other sectors. This allows people the flexibility to live at great distance to work in remote exurbs or even a neighboring metropolitan area.

But commuting is just one—albeit a key—way to show regional cohesion. Other integrating forces exist such as goods movement, business linkages, cultural commonality, and physical environment. A Megapolitan Area could represent a sales district for a branch office. Or, in the case of the Northeast Megalopolis or the Florida Peninsula, it can be a zone of fully integrated toll roads where an “E-Z Pass” or “SunPass” works across multiple metropolitan areas.

Lang and Dhavale (2005a) define Megapolitan Areas with the following list of characteristics:

• Combine at least two, but may include dozens of existing metropolitan areas;

• Total at least 10,000,000 projected residents by mid century;

• Derive from contiguous metropolitan and micropolitan areas;

FIGURE 1. The 11 U.S. Megapolitan Areas.

TABLE 1. Hierarchy of U.S. Urban Complexes

Type | Description | Examples |

Twin City | Two principal cities that physically connect to form a binary core to a metropolitan area | Minneapolis/St. Paul, Tampa/St. Petersburg |

Metroplex | Two or more metropolitan areas that share overlapping suburbs but the main principal cities do not touch | Dallas/Ft. Worth, Washington/Baltimore |

Extended Metroplex | Two or more metropolitan areas with anchor principal cities over 75 miles apart that maintain at least 5 percent of commuting spillover between metros | New Orleans/Baton Rouge, Tampa/Orlando |

Megapolitan Area | Three or more metropolitan areas with main principal cities over 75 miles apart that form an urban web over a broad area but do not maintain commuting linkages | Gulf Coast, Great Lakes Crescent |

Megapolitan Pair | Two megapolitan areas that are proximate and occupy common cultural and physical environments and maintain dense business linkages | Gulf Coast and I-35 Corridor, Sun Corridor and SoCal |

Source: Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech.

• Constitute an “organic” region with a distinct history and identity;

• Occupy a roughly similar physical environment;

• Link large centers through major transportation infrastructure;

• Form a functional urban network via goods and service flows;

• Create a geography that is suitable for large-scale regional planning;

• Lie within the United States;

• Consist of counties as the most basic unit.

In Figure 1, the eleven Megas are depicted by the bold outline. The map also shows Interstates and “urbanized” places.

There are several distinct levels of the urban hierarchy at which New Orleans connects to the larger network of regional metropolitan areas. Table 1 shows these relationships. While New Orleans and Baton Rouge do not form a tight metroplex in the way that Dallas and Fort Worth do, they do combine into what I define as an “extended metroplex.” For example, the centers of New Orleans and Baton Rouge lie at about double the distance as the gap between Dallas and Fort Worth. An extended metroplex maintains high degrees of connectivity by even such standard census measures as commuting, although its numbers in this measure fall just below what the census uses to define a “combined statistical area.”2

At the megapolitan level, the New Orleans area links to Houston as part of the Gulf Coast. Connections at this tier in the hierarchy include stretch commuting, transportation linkages, similar environment, and business networks. Finally, at the top of the urban system, are Megapolitan Pairs. The Gulf Coast forms a pair with the I-35 Corridor area, especially in Texas.

The degree of regional cohesion drops with each level in the urban hierarchy. Space within a metropolitan area is significantly integrated and is recognized by the census as such. The partners in an extended metroplex—such as New Orleans and Baton Rouge—fall just below a metropolitan designation and level of connectivity. The links are still present, but less intense at the megapolitan scale, and are more tenuous at the pair level.

The dispersal of people and commerce due to Katrina reveals the degree of integration in the urban hierarchy. As predicted, Baton Rouge, the metropolitan area that with New Orleans forms an extended metroplex, was most impacted by the dislocation of people from Katrina. The city of Baton Rouge almost overnight became the largest in Louisiana in the wake of the storm. Traffic snarled and house prices shot up as evacuees jammed the region. Business Week observed:

And the influx of displaced persons [from New Orleans] has helped boost tax revenues in the state capital of Baton Rouge, where property prices (and by extension property tax assessments) have risen, while federal aid is expected to help offset the costs of dealing with evacuees from metro New Orleans. (McNatt and Benassi 2006, 41)

Houston was the next most affected metropolis after Baton Rouge. Houston is the Gulf Coast’s leading metropolitan area, with about half the region’s population, and as predicted in the megapolitan model it has played a significant role in aiding New Orleans. In fact, so many former residents of New Orleans now live in Houston that the Crescent City’s current mayoral candidates make regular campaign stops in the city. That is because Houston is home to “150,000 evacuees, or almost as many New Orleanians as New Orleans” (Franks 2006, A1).

Evacuees from Katrina also affected Dallas, but not nearly to the extent they did Baton Rouge and Houston. Still, the city was affected enough to ask for and receive federal aid to offset its costs due to aiding displaced people. Dallas, along with other I-35 Corridor metros such as San Antonio and Austin, form a Megapolitan pair with the Gulf Coast. The New Orleans Saints— the professional football team—moved from its home in the Superdome to the San Antonio Alamodome for the 2005 season.3 Austin had enough Katrina evacuees to set up a resource guide website and schedule community events for hurricane victims. Thus even mid-sized metropolitan areas—500 miles from New Orleans—played a role in its recovery.

NEW ORLEANS AND THE GULF COAST MEGAPOLITAN AREA

New Orleans is not the Gulf Coast’s premier “world city.” That role is played by neighboring Houston, according to analyses by Taylor and Lang (2005, 2006). Their studies looked at business connectivity between world cities, based on the network of headquarters and branch offices in producer services such as banking, finance, law, insurance, media, accounting, advertising, and management consulting. The two leading world cities were found to be New York and London. Houston was the tenth most connected U.S. world city, while New Orleans ranked thirty-seventh—below Las Vegas and ahead of Sacramento. New Orleans ranked well below such other non-Gulf Southern U.S. metro rivals as Miami (fifth), Atlanta (sixth), and Dallas (ninth).

That Houston ranks higher as a world city than New Orleans should not surprise those familiar with the Gulf Coast. For instance, airline connections to New Orleans often run through Houston. Taylor and Lang’s data showed that New Orleans was heavily connected (and subordinate) to Houston in terms of producer services. Houston typically has the headquarters, and New Orleans the branch office. While Taylor and Lang did not focus on shipping and energy, it is likely that Houston maintains the same command position with respect to New Orleans in these sectors.4 In general, Houston is the key gateway in and out of the Gulf Coast, while New Orleans constitutes an important secondary regional hub.

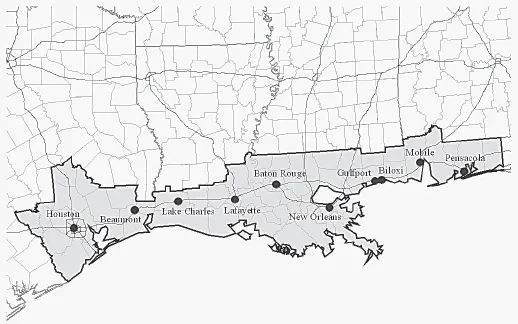

The New Orleans metropolitan area, with 1.36 million residents (in 2004), lies near the middle of Gulf Coast Megapolitan Area that stretches from Pensacola to Houston (see Figure 2). The Gulf Coast region features an unbroken string of nine census-defined metropolitan areas (and six surrounding rural counties) that together contain almost 10.4 million people (see Table 2).

Metros along the Gulf Coast share many environmental and economic attributes (Lang and Dhavale 2005a). First and foremost, the entire region is vulnerable to hurricanes. Most urbanized growth is near the Gulf of Mexico, and lies between wetlands and estuaries. New Orleans is famous for being mostly below sea level, but the Gulf Coast’s other major metropolitan area— Houston—is also quite low, having been built over and around a series of bayous. New Orleans is not the only city along the Gulf Coast to rely on pumping systems and levees to stay dry—only the most notable one.

The Gulf Coast region contains large tourist, energy, fishing, and port-related economies. The energy sector is quite diverse and includes oil and natural gas extraction, refining, and financing. Metropolitan Houston and New Orleans have producer service firms that specialize in multiple energy sectors from finding new energy sources to extinguishing oil well fires. Houston is also home to energy futures markets, the best-known example of which was run by the now defunct and scandal ridden firm Enron.

FIGURE 2. The Gulf Coast Megapolitan Area.

TABLE 2. Gulf Coast Metropolitan Population, 2004

Metropolitan Area | 2004 population (est.) | Number of counties/parishes |

Baton Rouge-Pierre Part, LA CSA | 751,965 | 10 |

Beaumont-Port Arthur, TX MSA | 383,443 | 3 |

Gulfport-Biloxi-Pascagoula, MS CSA | 409,045 | 5 |

Houston-Baytown-Huntsville, TX CSA | 5,280,752 | 12 |

Lafayette-Acadiana, LA CSA | 524,163 | 6 |

Lake Charles-Jennings, LA CSA | 225,877 | 3 |

Mobile-Daphne-Fairhope, AL CSA | 557,227 | 2 |

New Orleans-Metairie-Bogalusa, LA CSA | 1,363,750 | 8 |

Pensacola-Ferry Pass-Brent, FL MSA | 437,135 | 2 |

Imbedded Rural Counties in LA and MS | 429,008 | 6 |

Gulf Coast Megapolitan Area Total | 10,362,365 | 57 |

CSA = Combined Statistical Area; MSA = Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The biggest impact from the two Gulf Coast 2005 hurricanes Katrina and Rita were felt in the New Orleans, Gulfport, Lake Charles, and Beaumont metropolitan areas, or places that are home to nearly 2.4 million residents (see Table 2). This is a big impact, but represents less than a quarter of the total population of the Gulf Coast Megapolitan Area.5

WHERE DID NEW ORLEANS GO AND WHO WILL RETURN?

Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans is still not fully understood, but the preliminary data show that it may be the most devastated American city since the destruction of Atlanta during the Civil War. The best evidence available on the human dimensions of Katrina in the immediate aftermath of the storm was gathered by the news organizations, especially USA Today. USA Today obtained information about the dispersal of population from the city. It used two sources: the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the United Stat...