![]()

CHAPTER ONE

New York and the Global Market

AMERICAN HEROIN USERS had their own nation, and New York City was its capital. Not only has New York organized the heroin trade both nationally and internationally since the 1920s, it has also hosted the nation’s largest population of heroin users. Heroin passed from an international trading system into a national one in New York, which then redistributed heroin to other cities throughout the country. New York served as the central place that established the hierarchical structure of the market, with virtually the entire country as its hinterland and other cities serving as its regional or local distribution centers.1 However, the world trade in heroin is based on a raw material, opium, which is not native to the United States, so it is reasonable to ask how New York City came to play a central role in the world market. The answer to that question lies in the politics of opium and its conversion into an illegal commodity.

Opium poppies are relatively easy to grow, which has always made controlling their supply difficult. Many regions of the globe now produce poppies in a process of proliferation that has accelerated over time. In the ancient world, poppy growing occurred first in Egypt, and then spread into Persia (Iran), India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Turkey, the so-called “Golden Crescent.” The poppy followed Arab traders into Asia, and the “Golden Triangle” of Burma (Myanmar), Laos, and Thailand became a major source for the global market in the mid-twentieth century. China began growing poppies in the nineteenth century to serve its population of opium smokers, while Mexico and Latin America began to export opiates in the twentieth century to supply the U.S. market. European countries—including Greece, Bulgaria, Russia, the Balkan states, and even Britain—all produced opium poppies at one time or another. As different states attempted to regulate the cultivation of opium, entrepreneurs drew new regions into the opium trade. Again and again, the opium poppy escaped like a wisp of smoke from the grasp of those who sought to control it.

Not all poppies are created equal, however. The opiate content of poppies grown in different regions of the world varies considerably, as does the desirability of the opium they produce. The richest opium poppies are from Southwest and Southeast Asia, while European and Latin American poppies have lesser opiate value. Nonetheless, even the less desirable poppies find a market, especially in times of shortages elsewhere. The supply of opium poppies may not be infinite, but it is nearly so, which indicates the problem faced by international control efforts. Poppy cultivation has spread across the globe in response to the demand for opiates and in reaction to opium controls, and opium poppies have become an unbeatable cash crop in poor regions that cannot otherwise enter the market.

Poppy cultivation requires a small investment in technology and capital, which makes it an appealing crop in poor areas. Opium poppies are hardy and need plentiful sun, not too much rainfall, and modestly rich soil, but little irrigation and few pesticides or fertilizers. Poppies spread naturally into the furrows left by the cultivation of staple crops, and thus allow farmers to use their fields intensively. While cultivation is not difficult, harvesting is a laborious process that is difficult to mechanize and requires an abundance of inexpensive labor, which is usually readily available in less developed regions of the world. The opium poppy typically produces white, pink, or purple flowers, and a small bluish-green pod that laborers cut by hand. A sticky, milky-white substance oozes out of the pod and is hand-scraped with a small blade and collected into balls that, when dried, boiled, and strained, becomes morphine base, the source of manufactured opiates.2

Although opium has important medical uses, its conversion into a commodity of mass consumption in the nineteenth century dominates its modern history. European traders introduced tobacco, the tobacco pipe, and opium into China, and the practice of smoking a mix of tobacco and opium developed as a malaria preventative in China’s coastal regions. Eventually the Chinese converted this into a recreational practice, discarding the tobacco and smoking opium in opium houses while consuming tea and delicacies in the company of friends. The population of opium smokers exploded in the mid-nineteenth century after Britain defeated China in the opium wars and forced it to legalize the opium trade. By 1900, China consumed 95 percent of the world’s opium crop, and over sixteen million Chinese smoked regularly.3

The practice of smoking opium followed the Chinese throughout the world, including to the United States. Opium smoking occurred in opium houses in American Chinatowns, and initially the Chinese were the drug’s primary consumers. However, opium smoking gradually leaked into the urban underworld. In many cities, the police tolerated vice, such as prostitution and gambling, as long as it took place within specifically designated districts, and often these vice districts overlapped with Chinatowns. As these communities mingled, the practice of smoking opium spread, and by the end of the nineteenth century, it had become popular among prostitutes, criminals, entertainers, and other habitués of the “sporting life.”4

Concerns about the alleged goings-on in “opium dens” inspired the first domestic attempts to control opium. The association of whites, particularly white women, and Chinese men in opium smoking parties led municipalities to impose fines and authorize imprisonment for operating or patronizing an opium den. Scenes such as one described by a San Francisco physician of “young white girls from sixteen to twenty years of age” lying around “half-undressed on the floor or couches” in mixed-sex and mixed-race smoking parties fed the public outcry.5 Congress first imposed increasingly high duties on opium, then forbade Chinese merchants from importing it. Finally, in 1909, Congress acceded to racialized fears about opium smoking and passed a ban (the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act) on opium imports for nonmedicinal purposes, as part of a worldwide movement to restrict the opium trade.6

Smoking opium was the most vilified, but not the most common, form of opium consumption in the United States in the nineteenth century. The oral ingestion of opium was central both to medical practice and to commercial and home remedies for common ailments, and this led to more abuse than smoking opium did. Laudanum—as well as widely available patent medicines, syrups, and tonics—contained opium as the principal ingredient, and opium was one of the few effective forms of pain control. Physicians used opium pills to relieve a wide variety of symptoms, such as diarrhea and coughs, and women frequently resorted to opium-based medications to ease menstrual cramps. While morphine became an effective pain reliever after the introduction of the hypodermic syringe (1853), its use was limited largely to those able to afford medical care, and so opium remained a mainstay of the nineteenth-century home medicine cabinet. With the notable exception of Civil War veterans and Chinese and underworld opium smokers, the typical American opium user was a middle-aged white woman of middle-class background who had become habituated to opium through self-medication.7

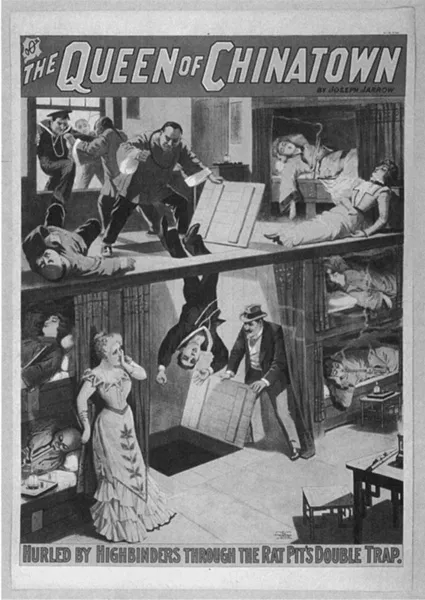

A poster for the play The Queen of Chinatown, c. 1899, with its images of white women in languid, opium-induced repose, Chinese opium smokers, sailors being dropped into a rat pit, and menacing gangsters illustrates the anti-Chinese themes that motivated opium-control efforts. Theater Poster Collection, Library of Congress, LC–USZC4–583.

By the early twentieth century, the use of oral opiates was declining. The commercialization of aspirin by the German pharmaceutical company Bayer in 1899 established an effective substitute for many common medicinal uses of opium. Then, following the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act (1906), companies changed the ingredients in their over-the-counter nostrums as consumers became more aware of the dangers of the drugs they took. Finally, physicians became more careful about dispensing narcotics so that fewer patients were likely to become addicted to opiates following medicinal use. As per-capita opium consumption fell in the United States, a shift occurred in the profile of the average opium user that made the passage of prohibitory legislation—aimed at “deviant” users—easier.8

With fewer middle-class women using opium, the average user became a white male member of the urban working class, who took opiates for recreational purposes. These young men lived on the margins of respectable society and enjoyed little public sympathy for their drug use. Charlie, born in Greenwich Village to Italian parents, left school at fifteen and learned to snort heroin from fellow workers in a chandelier factory. Similarly, Jerry, who grew up in Williamsburg in Brooklyn, began using heroin at a young age, claiming “I was a youngster when I took the first shot in the arm [at age fifteen].” He had started snorting heroin with other young workers from the candy factory where he was employed, but he did not like the effect. Soon after he started taking a “joy shot” once in a while, and reacted more favorably, becoming a life-long heroin user.9

Controlling the drug use of working-class men such as these became an argument in favor of federal control over domestic narcotics consumption. The Harrison Act (1914) became the basis for prohibiting the nonmedicinal use of any narcotic drugs, and its passage culminated decades of effort, both nationally and internationally, to limit access to the opiates and cocaine.10 By the early twentieth century, the outlines of both the international and the domestic narcotics prohibition policies that dominated the rest of the century were largely in place.

The passage of the Opium Exclusion and the Harrison Acts certainly had an impact on opiate users, but not the ones legislators intended. Restrictions on smoking opium forced users to switch drugs, either to morphine or heroin, which also became the drugs of choice for new opiate users.11 Both of these drugs were more dangerous for users than opium smoking. While the practice of smoking opium was not benign, it was a relatively inefficient means of transmitting a small dose of opiates to the lungs and brain. Some opium smokers became addicted, but many others limited the number of times and the number of pipes that they smoked because of the elaborate, time-consuming preparations and rituals involved in using the drug.12 Because morphine and especially heroin were so powerful, sniffing or injecting the drugs delivered a far higher dose of opiates to the body, which increased the possibility of addiction. Since retail dealers cut heroin heavily with quinine, mannitol (a children’s laxative), milk sugar, or any other white powder that was handy in order to increase their profit, users did not know the purity of the drug or the cutting agents with which it had been mixed. This increased the possibility of an overdose if the drug were unusually strong or an allergic reaction to the combination of ingredients in the cut. Adding to the danger, morphine and heroin use, while not necessarily solitary, were less ritualized than opium smoking, and less adaptable to the social controls established by fellow users. Therefore users were more prone to overindulge and increase their consumption over time.13

Prohibitory legislation, except for a short period when narcotics clinics dispensed opiates legally, forced these users underground and led to the creation of a thriving black market that became centered in New York.14 While white opium users in most parts of the country changed to morphine, those in New York switched to heroin, which was first introduced commercially as a pain reliever and cough suppressant by Bayer in 1898, and eventually took over the national market for opiates.

Heroin use clustered in New York because it was home to the nation’s major pharmaceutical companies. These companies produced heroin legally for the medical market until 1924, when additional federal legislation prohibited the practice. Like their European counterparts, American companies manufactured more heroin than the legitimate market could absorb, with much of the excess being sold illicitly.15 New Yorkers therefore led the switch from opium to heroin, which became entrenched among the city’s opiate users by the 1920s. As the legal production of heroin was eliminated in the United States and as legal manufacturing of heroin abroad became more closely regulated, underground factories, first in Europe and then in China, began producing heroin for export to the New York market.16 These international sources supplied heroin to illicit wholesalers, and as a result heroin use spread outward from New York and gradually replaced morphine in the illegal markets in the rest of the country.17

A bent spoon, used to “cook” heroin, along with various syringes, drug paraphernalia, and a heroin tin, hidden in a shoe, were all confiscated from patients entering the Federal Narcotics Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. New York World Telegraph and the Sun. Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

As an illegal commodity, heroin had distinct advantages over both opium and morphine, which explain its market dominance. It was more powerful than either drug, and it offered a ready solution to the basic problem of smuggling, namely reducing the ratio of volume to value. Smugglers found that it was easiest and most efficient to smuggle the item with the highest value and lowest volume, which in this case was heroin. Because opium was simply too bulky and smelly to smuggle easily, opium traders wanted to convert crude opium into morphine base, which reduced its volume by about 90 percent, at the earliest possible stage in the smuggling process. As the conversion process was relatively simple, it usually occurred near the site of agricultural production. Morphine base withstood the rigors of smuggling, but it was a “semi-finished” product that required additional and more complicated chemical processing in order to be transformed into morphine and then into heroin. Skilled underground chemists handled the tricky manufacturing process in well-equipped and well-ventilated labs at a point close to final shipment. Since heroin was several times more powerful than morphine, it was the preferred product for smuggling: it had high value but low volume that could be expanded with adulterants once it had crossed through the bottleneck created by international controls.18

Using dirty needles and impure drugs resulted in abscesses on this man’s legs. New York World Telegraph and the Sun Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Once heroin took over the illicit opiate trade, New York’s fate was sealed. Geography and a history of underground entrepreneurship predestined New York to become the key site for the importation and distribution of heroin in the United States. With one of the world’s greatest harbors, rail and highway connections to the rest of the nation, and criminals with experience in the delivery of illicit services, the city possessed both the natural and the human resources needed to import and distribute heroin. Beginning in the 1920s, Jewish and Italian traffickers, bankrolled by the underworld financier Arnold Rothstein, made heroin purchases in China and Europe and smuggled them back to New York. Bootlegger Waxy Gordon, seeing the end of Prohibition looming, switched his product line to heroin, while mobster Louis “Lepke” Buchalter added heroin smuggling to his repertoire of homicide for hire (so-called Murder, Inc.) and labor racketeering.

World War II disrupted this international traffic temporarily. Importers eventually acquired inferior-grade Mexican heroin to supply the city’s and nation’s heroin users, but once trade connections were reestablished after the war, New Yorkers capitalized on their ties to heroin distributors abroad and reasserted the city’s role as...