![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Palace of Consumption

Such stores as the Silks and Dress Goods, the Laces and Suits, the Groceries and Horse Goods . . . set thrifty buyers on the jump. A dozen other places in the store are just as active. We mean that before long there shall not be a dull corner in the building. Be a little patient.

—Manly M. Gillam, Advertisement for Hilton, Hughes & Company, 1895

THE massive, ornate “palaces of consumption” of the late nineteenth century were in some ways the Wal-Marts of their era. Their founding families—with such names as Wanamaker, Straus (successors to Rowland Macy’s retail legacy), Gimbel, Filene, Hutzler, and Bamberger—joined forces with the wealthiest in the nation. Their mode of buying and selling challenged traditional forms of distribution, generating opposition and cries of monopoly from manufacturers and single-line merchants at the end of the nineteenth century.1 Shoppers, however, saw no threat. Like today’s Wal-Mart customers, they flocked through the doors to find everything under one roof at prices that undercut specialty stores. Innovations in advertising, merchandising, and display beckoned. Unlike Wal-Mart, however, the elegant doors of places like Marshall Field’s in Chicago were a portal to luxurious amenities and services. Also unlike Wal-Mart, these palaces of consumption were local institutions. Their founding families were deeply involved in the social and economic goings-on of their home cities; their names came to adorn college buildings, streets, and philanthropic foundations. Moreover, the appearance of big urban department stores did not obliterate Main Streets and Market Streets across the country but instead enlivened them. Where the big merchants built their multistoried stone and brick emporia, central business districts appeared. Streetcar lines were laid and city thoroughfares grew crowded with foot traffic and vehicles.2 When merchants moved within the city, retail districts followed. Such stores in fact helped create downtown, making it the place to be.

The introduction and expansion of this urban institution spanned the second half of the nineteenth century and corresponded with the great economic and social transformations of urbanization, industrialization, and immigration. The mass distribution counterpart to mass production, department stores facilitated the rise of a consumer society in major urban centers. By 1908, advertisers were heralding the department store as “the greatest channel for distribution of merchandise today.”3 Retail transformations initiated in cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago spread across the country as “progressive” merchants in smaller cities and towns also came to admire the department store’s ability to lower the costs of distribution. Older trade practices, however, hung on in these smaller communities. Even in big cities, the economic effect of large emporia was limited—nothing on the scale of mass retailing today. With few exceptions, these early departmentalized emporia were single-unit independents that could not command a national or even a regional market, except perhaps in their wholesale divisions. Most retail trade in the nation still took place in financially precarious mom-and-pop businesses and in the general stores that continued to serve rural areas.4 The department store, however, had been invented.

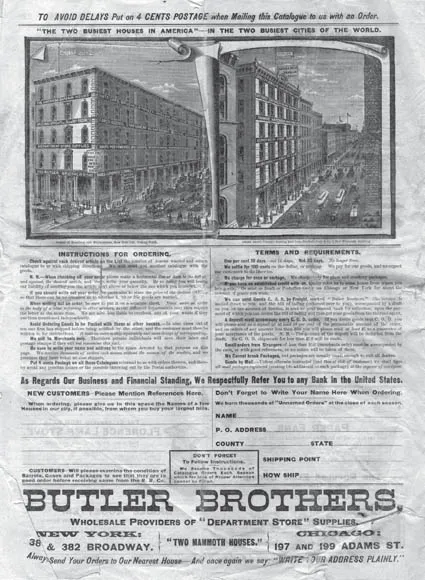

Origins

Department stores were the first mass retailers, but they were not the first mass distributors. As the speed, regularity, and dependability of transportation and communication improved in the second half of the nineteenth century, wholesalers became the first to use the modern multiunit enterprise to market goods on a mass scale. Well-financed wholesalers began to dominate the dry goods, drug, grocery, and hardware trade. By 1870, full-line, full-service wholesalers who owned their inventory replaced the commission agents or jobbers who had previously handled distribution for a fee without purchasing goods from the manufacturers. Wholesalers like Butler Brothers catered specifically to the new mass retailers, though some department stores preferred to buy directly from manufacturers in order to avoid the added cost of a middleman. Some became wholesalers themselves in order to cut out a link in the distribution chain. No matter which path they took, department stores moved toward tightening their hold on the supply of goods, cutting off the power of traditional wholesalers. Not surprisingly, with the emergence of different forms of mass retailing, such as mail order and department stores, the market share of wholesalers fell off after the early 1880s.5

Out of this context, the New York wholesaler/retailer A. T. Stewart developed a new system of merchandising that eventually transformed the way goods were bought, sold, and even manufactured. Beginning with a small shop in the 1820s, the Irish-born wholesaler-retailer built his famous white “marble palace” in 1846, a massive four-story Anglo-Italianate dry goods emporium on lower Broadway. Business flourished, and in 1862 Stewart spent $2.75 million of his fortune building “The Greatest Store in the World.” At Broadway and Tenth, this “iron palace” became a major attraction in New York with its imposing cast-iron facade painted to look like marble, hundreds of plate-glass windows, a grand staircase, central rotunda, and domed skylight. More than just an architectural wonder filled with beautiful things to admire and buy, A. T. Stewart’s introduced many of the features and policies that would become standard in all big department stores by the end of the nineteenth century.6

Stewart helped establish three major principles of modern selling—the one-price system, rapid stock turn, and departmentalized organization of goods. A set price eliminated the tradition of haggling, an age-old practice that required skill on the part of the seller and surveillance on the part of the owner. The one-price system was key to growth, allowing merchants to hire inexperienced clerks and cut labor costs. Good stock turn was also crucial as it represented the store’s ability to free up its capital to reinvest in more merchandise. Calculated as the number of times the store’s inventory turned over in a year (was sold), stock turn became a much-studied figure by modern, progressive merchants as the department store field matured in the early twentieth century. Other early innovations during this period included a purpose-built, multifloored building in a central location; a free entrance policy, meaning customers could browse at will; customer services such as merchandise return, delivery, restrooms, parcel wrapping, and checking; low markup; cash selling or short credit terms; large sales volume; centralization of nonselling functions; and stock clearance through bargain sales.7

FIGURE 2. A prominent full-line wholesaler, Butler Brothers supplied department stores across the country. Advertising Ephemera Collection, #A0673, Emergence of Advertising in America On-line Collection, John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History, Duke University David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Departmentalization became the defining feature of this new form of distribution, something that clearly distinguished it both from the jumble of the general store and from the narrowness of the specialty shop. Keeping voluminous accounts, the new type of retailer tracked profits and losses by departments—administrative units organized around the different lines of goods. Departmentalization also aided growth, permitting expansion on a scale not attainable by the general merchant. It allowed merchants to keep separate accounts for different kinds of stock and provided the statistics for dropping unprofitable goods and departments, as well as ineffective employees. Later, with the rise of ready-to-wear, merchants faced increased pressure to departmentalize, as new lines required differing sales appeals and distinct display and sales areas.8

Stewart’s departmentalization, however, was limited largely to dry goods, which were extremely popular in the age of home and custom production. Standard dry goods included muslins, calicoes, silks and satins, black goods for mourning, velvets, worsted goods, and laces, as well as embroidery and edging, linings, and notions—such things as needles, thread, and dressmakers’ tape.9 Dry goods emporia like A. T. Stewart’s and dry goods departments in major department stores also sold plush carpets and rugs, soft velvet chairs and couches, furniture covers, table scarves, curtains, draperies, and swags for shelves, mantels, and doorways. Women were the main consumers of these lines, and A. T. Stewart was one of the first merchants to make special appeals to them to ensure their patronage. Around these goods, he created a new kind of shopping environment for the female market, one that big-city department stores developed even further by the late nineteenth century. He and other dry goods merchants supplied the socially important cascades of fabric necessary to create a fashionable, middle-class parlor and woman’s dress in the Victorian era. Dressmaking and millinery departments, with craftswomen on staff, catered to middle-class women by the 1910s in major big-city stores like Macy’s, Gimbels, Filene’s, and Jordan Marsh. A woman planning her wardrobe and decorating her home shopped from an amazing array of imported and American factory-produced textiles at Stewart’s palace and even at smaller dry goods shops. While an emerging ready-to-wear industry supplied these emporia with such things as boys’ clothing, cloaks, and ladies’ underwear, sales of ready-to-wear clothing in department stores would not outpace fabric sales until 1920.10

Modern selling, as it took place in the many departments under Stewart’s roof, was tied to the innovative policy of free access. Stewart’s dry goods emporium became a new kind of place in the city where white middle-class women could stop in to relax, browse without buying, and socialize. By the mid-1890s, department stores were a major source of urban leisure for these women (and employment for others), a phenomenon that generated humor in the press with accounts of “the bread-winning end of the family” having their dinner hour delayed as their wives did their Christmas shopping and being “gently persuaded into putting out a little more money.” Stewart put amenities in place that actually encouraged such previously frowned-on behavior. For example, he was the first in New York to introduce revolving stools in front of counters, a feature that allegedly drew women shoppers from miles around just to rest their weary feet on shopping trips. Staffed by saleswomen and frequented largely by women shoppers, department stores would eventually become known as an “Adamless Eden,” a haven of sorts for middle-class women in the city, though not, perhaps, for the women who served them. As it was later remembered, Stewart’s iron palace served as “a great women’s club and was the place for hundreds of appointments each day for women who desired to see each other.”11

While A. T. Stewart was one of the better-known innovators of the department store form, other important figures joined him in this early rough-and-tumble period of mass retailing and wholesaling. H. B. Claflin was his main competitor. In 1864, Claflin was reported to have (likely grossly exaggerated) sales of $72 million. Although less prominent than Stewart, his dry goods wholesale business, then organized as Claflin, Mellin and Co., outsold Stewart’s better-known wholesale-retail firm. The two men’s tremendous success came in part out of their shared willingness to pursue self-interest ruthlessly. Stewart gained his position as the third richest man in the country, following William B. Astor and Cornelius Vanderbilt, through his merchandising genius but also through a calculating, hard-nosed approach to credit, and strict control over a labor force that eventually reached two thousand. One anonymous merchant in 1877 described Stewart as “one of the meanest merchants that ever lived.” Unlike Stewart, however, self-interest was not a part of Claflin’s public persona.12 Upon Claflin’s death in 1885, a memorial piece in the New York Times praised the merchant, contrasting his personality and policies with that of his famous contemporary. As portrayed in the press, Claflin was much loved by his contemporaries and was believed to have given many dry goods men across the country their start by providing training as well as capital. He was also believed by contemporaries to be liberal with the merchants who were his customers, giving larger credit and longer time than Stewart. Described as having a benevolent face and being “free from all airs, from all selfishness,” he was well known at the time for his trusting disposition and generosity, which also got him into trouble with hucksters. Press accounts, however, reveal a different assessment of the merchant’s character not visible in the laudatory piece published after his death. In 1870, for example, Claflin’s firm was investigated for selling shoddy blankets and other items at inflated prices to a jail to supply prisoners. At one point, he was also indicted for smuggling silk. After decades of double-dealing, scandal, and close encounters with the law, his firm was incorporated in 1890 and the business was carried on by Horace Claflin’s son John.13

Although both Claflin and Stewart were major figures in the history of nineteenth-century distribution, they never saw their businesses become full-fledged department stores. The innovation of chain organization, however, gave Claflin’s original firm greater longevity. By the turn of the twentieth century, H. B. Claflin’s was a multiunit, centrally owned operation, though it was not standardized in the manner of the tea and coffee chains of the time. Lacking the tight organizational structure, management supervision, and accounting control methods of later chains, Claflin’s was more subject to the personalities and idiosyncrasies of its proprietors as well as to the vagaries of the market. Personal troubles continued to follow the firm. Claflin’s partner, for example, died of a chloroform overdose while being treated for a morphine addiction. Eventually, H. B. Claflin’s overextended itself and collapsed, but it was reorganized to become one of the first department store chains in 1916, the Associated Dry Goods Corporation.14

As the strange story of H. B. Claflin’s suggests, the path toward the big department store chains of our era was not straightforward, nor was it populated only by success. The end to A. T. Stewart’s story supports this as well. Within two decades after his death in 1876, Stewart’s massive fortune was drained and his international merchandising organization run into the ground by the two executors of his estate, his legal advisor Henry Hilton and his business partner William Libbey, both of whom took advantage of the third executor, Stewart’s widow. Hilton and Libbey reorganized the firm with themselves as partners and ran the dry goods emporium under its original name. In 1882, their partnership was liquidated after six years of inept management, poor judgment, and several scandals involving Henry Hilton’s exclusion of prominent Jews from a hotel he owned, a feminist protest against his reneging on a promised philanthropic gift of a working women’s hotel, and his inaction after the theft of A. T. Stewart’s corpse from his crypt. Over the next fourteen years, Henry Hilton put Stewart’s fortune into two more reincarnations of the original company, E. J. Denning & Co., followed by Hilton, Hughes & Co., both which drew on the good name of their more famous predecessor by always including the phrase “Successors to A. T. Stewart & Co.” below their name in advertisements and catalogs.15

Although A. T. Stewart was a department store pioneer in many ways, his influence should not be overstated. The rise to mass retailing did not occur quickly or cleanly. Pushcart vendors and pedd...