![]()

Part IV

Social Policy Matters

![]()

Chapter 12

Social Issues Lurking in the Over-Representation of Young African American Men in the Expanding DNA Databases

TROY DUSTER

In early May 2007, the governor of New York announced a plan to expand the state's criminal forensic database by requiring DNA samples from “those found guilty of any misdemeanor, including minor drug offenses” (McGeehan 2007). While several commentators were invited to reflect on some of the social consequences of this proposal, not a single word in the report or in the governor's plan mentioned the 800-pound gorilla in this database: race. Even the most cursory review of incarceration rates by sex, race, and age reveals an astonishing level of overrepresentation of young black males in the nation's prisons and jails. A striking but not atypical case is Washington State, where in 1998 blacks were only 3 percent of the general population, but 23 percent of the prison population (Palmer 1999).

To put this situation in recent historical perspective, in 1970 there were approximately 133,000 blacks in prison in the United States. Just three decades later, that figure had increased a stunning sevenfold, and by the year 2000, one million blacks were behind bars. In this essay, I explain the dramatic social and political implications of the racialized character of what may appear at first glance to be a race-neutral expansion of DNA databases.

Geometric Expansion of the National DNA Forensic Database

When criminal justice officials began collecting and storing DNA evidence in the early 1980s, the cases were always about sex crimes. Three factors converged to make this practice acceptable to politicians and the public: sex offenders are those most likely to leave body tissue and fluids at the crime scene; they rank among the most likely repeat offenders; and their crimes are often particularly reprehensible because they violate other persons, in acts ranging from rape to molestation and abuse of the young and most vulnerable. The rationale for having a DNA database of sex offenders was clear. By the mid-1980s, most states had begun to collect and store forensic data for those convicted of sexual crimes. In the ensuing two decades, these databases have expanded to include not only sex offenders and people convicted of violent crimes but also those convicted of felonious assault, arson, and a host of other crimes against property.

Today, all fifty states store DNA samples of sex offenders, and most do the same for convicted murderers (Simoncelli 2006, 1). But the original rationale seems inapplicable to the types of cases now included in the forensic database, such as burglary, car theft, and mere misdemeanors. In an even more dramatic departure from the original purpose, the federal government and six states now collect and store DNA from anyone even arrested (Simoncelli 2006). Why is the policy of storing the DNA of anyone who is arrested such a potentially explosive issue? The answer lies in the social patterns of arrest, independent of whether there are adequate grounds for specific arrests.

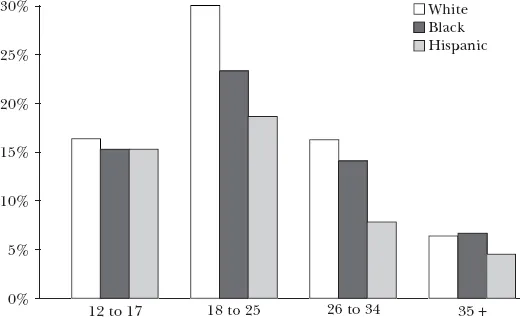

Comparing data on marijuana use with data on arrests for marijuana possession among youth who belong to different racial-ethnic groups reveals a significant bias: whites, who are more likely to use marijuana, are less likely to be arrested for possessing it. Figure 12.1 shows patterns of marijuana use by race and ethnicity. Among all those under thirty-five, who are most likely to be arrested, whites' rates of marijuana use actually exceed those of Blacks and Latinos.

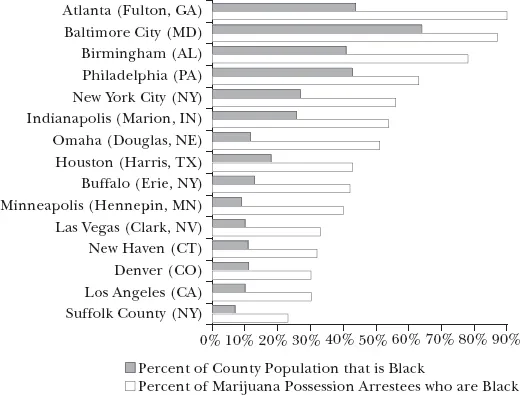

Figure 12.2 shows a remarkably different arrest pattern for marijuana possession. In fifteen major metropolitan areas across the U.S., blacks are arrested, routinely and systematically, at about twice their proportions in the local population. Atlanta, Georgia, tops the list; 90 percent of all those arrested for marijuana possession are black, while only about 45 percent of the population is black. The story is very similar in every jurisdiction: only about a quarter of New York City's residents are black, but well over half those arrested for marijuana possession in New York are black.

How do we explain the fact that blacks are twice as likely as whites to be arrested for marijuana possession, yet are less likely to possess marijuana than whites? The answer lies in U.S. government policy, which dates back to a 1987 decision by law enforcement officials to train law enforcement personnel to “stop and search” suspects based on a particular social profile.

Figure 12.1. Age of last year of marijuana use, by ethnic group. SAMHSA Office of Applied Studies, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1997. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/?NHSDA/1997Main/?nhsda1997mfWeb-27.htm#, Table3.5.

Operation Pipeline as the Major Funnel to the DNA Tunnel

In 1986, the federal Drug Enforcement Administration initiated Operation Pipeline, a program designed in Washington, D.C., that trained 27,000 law enforcement officers in 48 participating states over the ensuing decade. The project was designed to alert police and other law enforcement officials to “likely profiles” of those who should be stopped and searched for possible drug violations. High on the list are young, male African Americans and Latinos driving in cars that signal that something might e amiss. For example, a nineteen-year-old African American driving a new Lexus would be an “obvious” alert, based on the assumption that the family could not afford such a car so the driver must be “into drugs.”

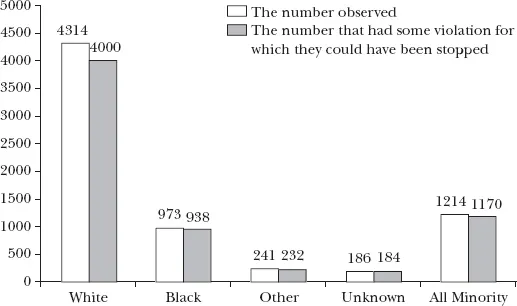

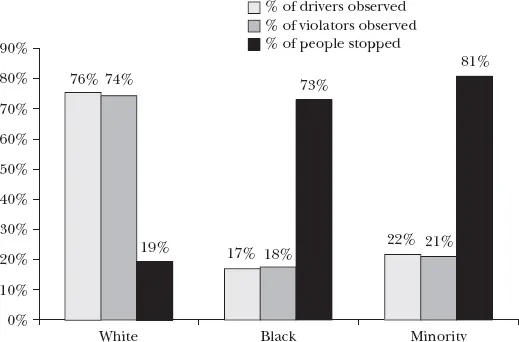

In a study of the I-95 highway corridor just outside Baltimore, police records indicated that Latinos and blacks were eight times more likely to be stopped by police than were whites (Duster 2004). A young white male in his early twenties driving a Lexus would not be considered “suspicious” since the police are likely to assume that he is driving the family car. In this real-life example, we can see that if we control these statistics for class, we still find a racial difference; see Figures 12.3 and 12.4.

Of course, many appreciate that DNA evidence can be and has been used to exonerate the innocent. But, while there have been only a few hundred exonerations of the wrongfully convicted, thousands languish behind bars because of prosecutors' claims of a match of DNA evidence. Despite public perceptions to the contrary, fueled by television drama series, movies, popular novels, mystery stories, and other fictions, jury trials are the exception. Fewer than 10 percent of those serving time in prison have been convicted by a jury. The overwhelming majority of convictions are secured by a plea bargain, a deal done out of public sight between the prosecutor and the defendant's legal representative—typically the Public Defender in the case of young black males. This is where the racial bias in the collection of DNA evidence has the greatest potential to produce a high level of unexamined social and racial injustice.

Figure 12.2. Racial arrest pattern for marijuana possession, fifteen metropolitan areas.

In September1999, Louisiana passed the first state law permitting DNA samples to be taken from all those arrested for a felony (Tracy and Morgan 2000). Four other states quickly followed. Today, thirty-eight states include some misdemeanants' samples in the DNA databank. Twenty-nine states require that tissue samples be retained in their DNA databanks after profiling is complete (Kimmelman 2000, 211); only Wisconsin requires the destruction of tissue samples at that point. While thirty-nine states permit expungement of samples if charges are dropped, destroying the sample and permanently removing the DNA from the database, almost all those states place the burden on the individual to initiate expungement. Civil privacy protection, which in the default mode would place the burden on the state, has been reversed.

Figure 12.3. Drivers stopped, by race, I-95 North Corridor, January 1995 to September 1996. Maryland State Police files, http//www/aclu.profiling/report/index/html Gray: number observed; black: number with some violation for which they could have been stopped.

What started as a tool to deal with sex offenders has now “crept” into a way to “capture” those arrested on far less serious charges. Citizens should worry about what policy analysts have come to call “mission creep,” which occurs when a policy intended for one specific purpose “creeps” or expands into many other uses—for example, when a military mission is extended to accomplish political goals. The best example is the history of the Social Security number. When the idea was first introduced in the mid-1930s, skeptical members of Congress warned that it could become the equivalent of a national identification card. Advocates assured the Congress that the Social Security card would only be used to track and allocate employment-related benefits. With clear hindsight, we can see how “mission creep” has affected the Social Security Number during the ensuing seven decades. A similar trend is already visible regarding DNA samples.

On January 5, 2006, President George W. Bush signed into law HR 3402, the Department of Justice's reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act of 2005. This legislation for the first time permits state and federal law enforcement officials to enter DNA profiles of those arrested for federal crimes into the federal Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) database. Previously, only convicted felons could be included. Those DNA profiles will remain in the database unless and until those who are exonerated or never charged with the crime request that their DNA be expunged. The default will be to store these profiles, and getting them expunged requires vigilance and vigorous proactive behavior on the part of those arrested. Given their youth, low economic status, and lack of access to legal counsel, the overwhelming majority will not even know of their right to have this information expunged.

Figure 12.4. Percentage of drivers stopped, by race, I-95 North Corridor, January 1995 to September 1996. Maryland State Police files http//www/aclu.profiling/report/index/html. Light gray: number of drivers observed; dark gray, number of violators observed; black, number of drivers stopped.

This expansion is certainly a boon for those in the business of providing DNA testing services. Just after President Bush signed the bill authorizing collection of DNA samples on arrestees, the chief executive officer of Orchid Cellmak, one of the leading providers of DNA testing, issued a statement applauding this development:

This is landmark legislation that we believe has the potential to greatly expand the utility of DNA testing to help prevent as well as solve crime…. It has been shown that many perpetrators of minor offenses graduate to more violent crimes, and we believe that this new legislation is a critical step in further harnessing the power of DNA to apprehend criminals much sooner and far more effectively than is possible today. (Orchid Cellmak press release, January 6, 2006, 1)

Twenty states authorize the use of databanks for research on forensic techniques. Based on the statutory language in several of those states, this research could easily mean assaying genes or loci that contain other types of information, even though current usage is restricted to analyzing portions of the DNA which are useful only as identifying markers. Since most states retain the full DNA (and every cell contains all the DNA information), it is a small step to using these DNA banks for other purposes. The original purpose has been pushed to the background, and the “creep” accelerates.

Biased Policies and Practices of Genetic Profiling

While the U.S. has been pushing ahead rapidly, the United Kingdom has been in the vanguard of these developments.1 In April 2004, a law was passed in the UK permitting police to retain samples from anyone arrested for any reason, including those who are not charged with a crime. Anyone can have their DNA taken and stored. The database already contains 2.8 million DNA “fingerprints” taken from identified suspects; plus another 230,000 from unidentified samples collected from crime scenes.2 Samples are being added at the rate of between 10,000 and 20,000 per month.3 The aim is to have on file the DNA of a quarter of the adult population—a figure that exceeds ten million, making it by far the largest DNA database in the world. It was recently disclosed that nearly four in ten black males in the UK are in the forensic database, compared with fewer than one in ten white males (Randerson 2006). Civil liberties groups and representatives of the black community worry that this disparity is not only a sign of racial biases in the criminal justice system but will actually exacerbate them. Dominic Bascombe of The Voice, the black newspaper based in London, expressed his concern that these data reflect police attitudes more than they do the behavior of those apprehended: “It is simply presuming if you are black you are going to be guilty—if not now but in the future.” He called this “genetic surveillance” of blacks: “We certainly don't think it reflects criminality” (quoted in Randerson 2006). The reporter concluded: “Anyone in the database—and family members—can more easily be linked to a crime scene if their DNA is found there. This may be because they are a criminal, or because they visited the scene prior to the crime” (Randerson 2006).

When representative spokespersons from the biological sciences say that “there is no such thing as race” they mean, correctly, that there are no discrete categories that have sharp boundaries, that there is nothing mutually exclusive about our current or past categories of “race,” and that there is more genetic variation within “racial” categories than between them. All this is true. However, when Scotland Yard or the police force of Birmingham, England, or New York City want to narrow the list of suspects in a crime, they are not primarily concerned with tight taxonomic systems of classification with no overlaps. That is the stuff of theoretical physics and logic in philosophy, not the practical stuff of trying to solve crimes or the practical application of molecular genetics to health delivery via genetic screening—and all the messy overlapping categories that will inevitably be involved with such enterprises. For example, some African Americans have cystic fibrosis even though the likelihood is far greater among Americans of North European descent, and in a parallel if not symmetrical way some white Americans have sickle cell anemia even though the likelihood is far greater among Americans of West African descent. But in the world of cost-effective decision making, genetic screening and testing for these disorders are routinely based on common-sense versions of the phenotype. The same is true for the quite practical matter of naming suspects.

In 2000, the New York Police Department, with the urging and support of Mayor Guiliani, was chafing to use a portable DNA lab kit (Mathis 2000). New York Police Chief Howard Safir said that a DNA sample should be taken from “anyone who is arrested for anything” (Tracy and Morgan 2000, 665). This lab kit, which was developed by the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, emerged at the convergence of molecular genetics with concerns about the identification of criminal suspects. During the next decade, it is more likely that we will be using these technologies for purposes of forensics and law than to develop medical therapies. California passed a ballot proposition in 2004 that permits the collection and storage of DNA data not only on all felons but on some categories of arrestees and misdemeanants by 2008.

New York State has since 1994 collected fingerprints from persons receiving public assistance in order to prevent duplicate claims, but does not generally share those data with law enforcement. In New York, arrest records must be sealed, and employers cannot ask if a job applicant has ever been arrested, but only if he or she has been convicted. When a mere arrest triggers DNA sampling and storage, and when those samples are not expunged, the forensic record becomes analogous to stored radioactive waste, in that it keeps emitting its effect (Kimmelman 2000).

Population-Wide DNA Databases

Many scholars and public policy analysts now acknowledge the substantial and well-documented racial-ethnic biases in police procedures, prosecutorial discretion, jury selection, and sentencing practices. Racial profiling is but the tip of an iceberg (Mauer 1999). Racial disparities penetrate the whole criminal justice system, from biased policies of stopping and searching drivers all the way up to racial disparities in seeking the death penalty for a given crime.

If the DNA database is primarily composed of those who have been touched by the criminal justice system, and that system is pervaded by practices that routinely select disproportionately from one group, there will be an obvious skew or bias toward this group. Some have argued that the best way to handle the racial bias in the DNA database is to include everyone. But this proposal does not address the far more fundamental pr...