![]()

CHAPTER 1

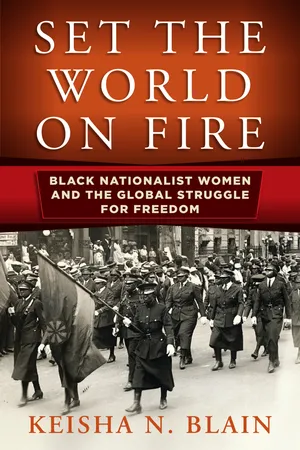

Women Pioneers in the Garvey Movement

ON APRIL 19, 1924, Eunice Lewis’s editorial, “The Black Woman’s Part in Race Leadership,” appeared on the women’s page of the Negro World—“Our Women and What They Think.” A member of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) residing in Chicago, Lewis crafted a succinct yet powerful article that embodied the spirit of the “New Negro Woman.” “There are many people who think that a woman’s place is only in the home—to raise children, cook, wash, and attend to the domestic affairs of the house,” Lewis noted. “This idea, however, does not hold true to the New Negro Woman,” she continued. The “New Negro Woman,” Lewis insisted, was intelligent, worked equally with men, was business savvy, and, most significantly, was committed to “revolutionizing the old type of male leadership” in the UNIA and in the community at large.1 Her comments, which coincided with the Harlem, or “New Negro,” Renaissance of the period, signified a key shift that was taking place within the Garvey movement.2

Founded by Marcus Garvey, with the assistance of Amy Ashwood, in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1914, the UNIA (originally the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League) was the largest and most influential Pan-Africanist movement of the twentieth century. Emphasizing racial pride, black political self-determination, racial separatism, African heritage, economic self-sufficiency, and African redemption from European colonization, Garvey envisioned the UNIA as a vehicle for improving the social, political, and economic conditions of black people everywhere. From Kingston, Jamaica, Garvey oversaw UNIA affairs before relocating to Harlem, where he incorporated the organization in 1918. At its peak, from 1919 to 1924, the organization attracted millions of followers in more than forty countries around the world.

Like many black nationalists before and after him, Garvey maintained a masculinist vision of black liberation and thus believed that black men would ultimately lead the fight to improve conditions for black people in the diaspora.3 Although he was not necessarily opposed to female leaders, Garvey sought to maintain a patriarchal model of leadership in the UNIA, which allowed women to serve as leaders only under the watchful eye of Garveyite men. Moreover, Garvey, as many other black men during the early twentieth century, endorsed Victorian ideals and exhibited the “spirit of manliness,” a masculine sensibility that emphasized black men’s respectability and ability to produce and provide.4 Along these lines, Garvey not only upheld the belief that men were the vigilant protectors of black women and children but also embraced the view that women’s natural place was in the home as wife and mother.5

Eunice Lewis’s call for “revolutionizing the old type of male leadership” was therefore a direct challenge to the prevailing ethos of black patriarchy in the Garvey movement. Along with a cadre of women during this period, including Amy Jacques Garvey, Maymie De Mena, and Henrietta Vinton Davis, Lewis articulated a new and expansive vision of black women’s leadership in the UNIA and in the community as a whole. These women, from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds and social positions, adopted a proto-feminist stance in which they directly challenged male supremacy and attempted to change the UNIA’s patriarchal leadership structure. In their efforts to “revolution[ize] the old type of male leadership,” black nationalist women pioneers created opportunities for women to have greater visibility and autonomy than Garvey originally envisioned. Moreover, they devoted significant attention to women’s issues and often defied prevailing gender conventions. In doing so, they articulated many of the same arguments and employed some of the strategies that were fundamental to feminist movements that emerged during the 1960s and 1970s.6

In addition to adopting a proto-feminist stance, women in the UNIA articulated several strands of black nationalism, drawing upon a rich and long tradition of black nationalist thought in the United States and across the diaspora. For example, they envisioned Africa as the homeland for black people and maintained the belief that black emigration would provide a means for black men and women to escape their second-class citizenship status and increase their political and economic power on a global scale. For many black nationalist women, Liberia represented the ideal location because of its ties to African Americans and its position as one of only two independent African nations during this period. Maintaining a cultural and racial bond with Africans on the continent and throughout the diaspora, women in the Garvey movement during the 1920s promoted Pan-Africanism and attempted to mobilize black men and women against racial discrimination, colonialism, and imperialism. They also advocated black economic self-sufficiency but did so within the framework of existing capitalist structures. To that end, they endorsed black capitalism, attempting to control the marketplace through the creation of black businesses and independent black institutions. By promoting all of these ideals, women in the Garvey movement played a pioneering role in twentieth-century black nationalism, laying the groundwork and theoretical foundations for the vanguard of nationalist women leaders who emerged in the three decades after Garvey’s 1927 deportation.

Amy Ashwood and the Birth of the UNIA

Marcus Garvey’s UNIA rose to prominence amid the social and political upheavals in the wake of World War I. A pivotal turning point in the history of the modern African diaspora, World War I, which began in 1914 and ended in 1918, mobilized thousands of black men to fight for the same democratic rights and privileges they were being denied at home.7 The war also created a labor shortage in the United States, which provided a crucial opportunity for black men and women from various parts of the globe to gain employment in northern cities. Perhaps most significantly, the war dramatically altered the political consciousness of peoples of African descent in profound ways. In the war’s aftermath, black men and women unequivocally rejected the racial discrimination that persisted in the United States and colonial territories in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. When the war ended in 1918, Afro-Caribbean migrants, for example, who had served in the British West Indies Regiment, openly revolted against the British in a series of uprisings that swept the region.8

These political uprisings, combined with a number of historical developments of the era, including the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia (1917) and race riots in the United States referred to as the “Red Summer” (1919), created an atmosphere in which the UNIA emerged as the largest and most influential Pan-Africanist movement of the twentieth century.9 Reflecting the rhetoric of self-determination, which gained increasing currency in mainstream political discourse after World War I, Garvey called on black men and women across the diaspora to help establish an autonomous black nation-state.10 In Garvey’s teachings, black men and women across the globe found the strategies and tactics to counter racial oppression and to advance universal black liberation.11

From the outset, black women were integral to the UNIA’s growth and success. In 1914, when Garvey launched the organization, Amy Ashwood, who later became his first wife, served as its cofounder and first secretary.12 Born in 1897 in Port Antonio, on the northeastern coast of Jamaica, Ashwood was one of three children and the only girl born of wealthy businessman Michael Delbert Ashwood and his wife, Maudriana (Maud) Ashwood (née Thompson). Shortly after Amy’s birth, the Ashwood family relocated to Panama City, where Amy’s father opened a bakery and restaurant during the construction of the Panama Canal. Concerned about the quality of education their children were receiving in Panama, Michael and Maud decided to bring the family back to Jamaica in 1904.

At age eleven, Amy began attending Westwood High School, a prestigious private school for girls that had been established by Reverend William Webb, a Baptist minister, in 1882. The first of its kind in Jamaica, Westwood provided an opportunity for all girls, regardless of class or race, to obtain quality educational training. There Ashwood was exposed to a diverse curriculum, which included courses in homemaking, biblical scripture, typing, and shorthand, as well as history, English, geography, mathematics, and science. Despite the first-rate education Westwood offered, the school’s curriculum was, in many ways, a reflection of the British colonial system. When she began attending the school, Jamaica, the largest of the English-speaking Caribbean islands, had been under British colonial rule for more than two hundred years. Similar to other students who attended schools in British colonies during this period, Ashwood was primarily taught British history and, as result, had very little knowledge about black history and culture.13

Later in life, Amy credited her ninety-three-year-old great-grandmother, Boahimaa Dabas—“Grannie Dabas” as she was called—for making her aware of her African heritage and igniting her race consciousness and growing sense of Pan-Africanism. At age twelve, Ashwood began to ask Grannie Dabas about her ancestors after an incident at school sometime in 1909. Recounting the event years later, Ashwood explained that teachers at Westwood had organized a mission fund that year to aid those in need. During a visit with Mrs. Webb, the wife of the school’s founder, Ashwood disclosed the amount of money she managed to raise for the mission fund and was startled when Mrs. Webb expressed disappointment that the money would not be sent to Ashwood’s “people” in Africa. “Being so young,” Ashwood explained, “I was very puzzled by this bit of news and naturally asked the lady many more questions about Africa.”14

Intrigued yet horrified by the information Mrs. Webb provided—about how black people had been captured by English slave traders on the shores of Africa and brought to Jamaica—Ashwood set out to find out more information about her ancestors. When her father became overwhelmed by the line of questioning, he took Ashwood to Grannie Dabas, who carefully recounted the difficult story of her capture on the Gold Coast at age sixteen and her life under slavery. According to Ashwood, her great-grandmother also described the “virility of her people and their prowess in war,” informing the girl that her great-great uncle was an accomplished military general of the Ashanti (Asante), one of the dominant ethnic groups in West Africa. This newfound knowledge of her family’s history awakened Ashwood’s racial consciousness and bolstered her confidence. “I was proud of myself [and] proud of my ancestry,” she recounted years later. “I went back to school with a feeling of innate pride. I had a country, I had a name. I could hark back to my genealogy.”15

By the time Ashwood met Marcus Garvey five years later, she had already developed a strong sense of race consciousness. However, her encounter with Garvey and subsequent relationship with him strengthened her interest in Pan-African politics. The two met in July 1914, when Garvey attended the weekly debate at the East Queen Street Baptist Church in Kingston. One of the featured speakers, Ashwood took the position that “morality does not increase with the march of civilization.” Garvey, who Ashwood later described as a “stocky figure with slightly drooping shoulders,” not only defended her point of view but also took the initiative to approach her afterward as she awaited her ride home. According to Ashwood, Garvey immediately expressed his love, declaring, “At last, I have found my star of destiny! I have found my Josephine!”16 By Garvey’s account, the encounter was far less dramatic. He only recalled being introduced to Ashwood by a colleague. Although the specific details of their initial encounter remain a mystery, what is certain is that the encounter between Garvey and Ashwood marked the beginning of a vibrant political relationship.

Together, Garvey and Ashwood worked in tandem to launch what would become the largest and most influential Pan-Africanist movement of the twentieth century. Drawing inspiration from Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Garvey envisioned the UNIA as a benevolent organization committed to Washington’s ideals of racial uplift, self-help, and social activism. Washington’s Up from Slavery (1901), which emphasized the significance of black education, had a profound effect on Garvey, who upon reading it experienced an epiphany of his calling to become a “race leader.”17 Ashwood shared similar views to Garvey and credited their mutual interests in Pan-Africanism and racial uplift as the driving force behind the creation of the UNIA. Describing their collective political vision during these early years, Ashwood noted, “Our joint love for Africa and our concern for the welfare of our race urged us on to immediate action.” “Together we talked over the possibilities of forming an organisation to serve the needs of the peoples of African origin,” Ashwood explained, “[and] we spent many hours deliberating what exactly our aims should be and what means we should employ to achieve those aims.”18 Working closely together, Ashwood and Garvey began planning the first UNIA meeting.

Although historians have debated the extent of Ashwood’s formal role in establishing the organization, none deny the fundamental importance of her organizational skills and social networks to the UNIA’s success.19 The organization’s earliest meetings, for example, were held...