![]()

1

_____

Two Working Women

Neither Mary Clarke nor Ann Carson expected to work outside the home, let alone become the sole breadwinner for her family. Necessity propelled them into the marketplace; illness, disability, and subsequent financial hardship forced both women to become economically resourceful (and, in the case of Clarke, creative). Although legal restrictions kept most women under feme covert status, many, like Carson and Clarke, crossed the boundary of domestic space into the public world of paid work.1 They were not alone. The early nineteenth century was an era of increased manufacturing and capitalization in the economic sector, but these advances were accompanied by an atmosphere of uncertainty and financial peril. First the embargo in 1807, then three years of war from 1812 to 1815, followed by the panic of 1819, all contributed to this insecurity. More women ventured into the marketplace as wage-earners and entrepreneurs. They did so in a complex, fluid, and risk-filled environment. These were the conditions under which Clarke and Carson made their economic choices.

The type of work Ann Carson chose was determined by her education and her social status. Carson’s father, Thomas Baker, had served on a privateer during the Revolutionary War and was held prisoner on the infamous Jersey prison ship in New York harbor. By the time of Ann’s birth in 1785, he was a ship’s captain employed by a Philadelphia shipping firm. Baker was able to keep his family in genteel comfort: he and his family lived in a style “suitable to his rank and fortune; the first being highly respectable, and the latter easy.”2 Affluence meant the Bakers enjoyed, as Ann recalled, “the luxuries of the West Indies” as well as “the delicacies of our plentiful city.” Ann described her childhood and youth as “scenes of perfect happiness unalloyed.”3

The Baker daughters received an education typical for young women of means in the late eighteenth century. Ann attended, by her own admission, “the best seminaries Philadelphia then afforded.”4 Though she did not specify which these were, the most famous school for young women, the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia, was not among them. Ann went to a coeducational school, and later condemned the practice of throwing the sexes together during their impressionable years. Ann became “complete mistress of my needle, and excelled in plain sewing and fancy work.”5 These attainments were expected of, and needed by, a middle-class woman who did not work outside the home. Ann, like her mother, was trained to run a household: supervise what few servants they could afford, perform some of the household work, keep accounts, educate children, and socialize with other men and women of her class. Like many seaport families whose fortunes were tied to commercial shipping in the late eighteenth century, the Baker family’s troubles began during the undeclared war with France, called the Quasi-War, in the 1790s. This conflict stemmed from the Jay Treaty; it stabilized commercial relations between the United States and Britain but it threw American relations with France into a tailspin. The Proclamation of Neutrality of 1793, intended to protect American ships from both the French and the British, was not honored by the British. Even worse, the British negotiated a truce with Portugal, which allowed the Algerian pirates free access to the Atlantic and enabled them to prey on American ships after 1793. The United States did not recognize these bandits as a legitimate power and refused to pay them tribute money. Thus, by the end of 1793, over 250 American ships had been seized. Philadelphia was one of the hardest hit ports, in part because of its trade with the French West Indies. All these incidents brought pressure to bear on the U.S. government to find a solution to ease the strain on commerce. But the Jay Treaty created as much controversy as it attempted to settle.6

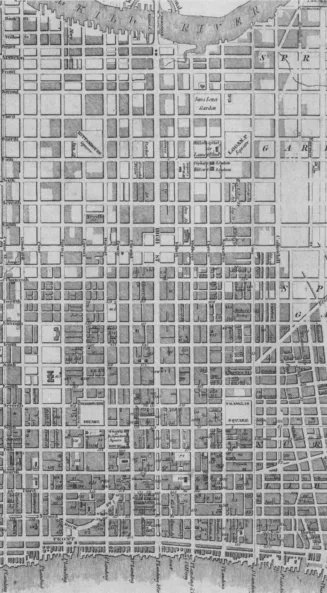

Figure 1. Map of Philadelphia. Most of the places Ann Carson and Mary Clarke lived and worked were in central Philadelphia. Carson’s china store was at Dock and Second streets, near the Delaware River. The two women later shared a house in the western part of the city, near the Schuylkill River. Detail of Map of the City of Philadelphia, drawn by J. Simons, published by C. P. Fessenden, 1834. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Thomas Baker, employed as a ship’s captain for Philadelphia merchants, was detained in France for eighteen months between 1794 and 1796. After his return to Philadelphia, Baker did not work for the next three years. Whether this was by choice or because of the difficulties with American shipping is unclear, though Carson suggested that her father may have declined to work, having “contracted a habit of indolence and a disgust to his profession.”7

Without a salary, the family lived on their accumulated savings, which were soon exhausted. When Baker finally resumed his career with the navy, he sailed to the West Indies, leaving behind a letter to his wife in which he informed her of their financial embarrassments. Jane Baker learned that they no longer owned the house they were living in. It was mortgaged to a Captain Davis, from whom Thomas Baker had borrowed money. Thomas Baker’s appointment as captain of the frigate Delaware secured the family a decent income, but only just. With no safety net and several debts to pay, the Bakers completely depended on Thomas’s earnings to keep them afloat. This security came to an end within a year. Baker, on assignment near Curacao in January 1800, contracted yellow fever. The disease (or perhaps the treatment for it) so affected Baker’s health that he retired from the navy in 1801. His memory was so compromised by his illness that, according to Ann Carson, he never again was capable of conducting any kind of business. The Bakers’ only source of income was Captain Baker’s pension.8

The Baker family, with five daughters and two sons, was considerably poorer than they had been a decade before. Ann and her mother and sisters, accustomed to a protected, privileged life free from money worries, now faced an uncomfortable truth: no male head of the household would support them and they were unprepared to provide for themselves. Ann lamented that her father’s pride, and his sense of what was proper for women of the upper reaches of the middle class, prevented his wife from contributing to the family income: “Had he permitted my mother to keep a shoe, grocery or grog shop, how at this time our family might have been opulent, and some of its [male] members probably lawyers, doctors, and even clergymen. The parents of numbers of our various professional characters were then of that class of society.”9

Ann Carson may have been thinking specifically about a family with whom she had uncomfortably close encounters on several occasions in the late 1810s. The fortunes of the Merediths exemplified the rapid economic and, equally important, domestic transformations that eluded the Baker family. Jonathan Meredith, a successful tanner, began his career in the 1770s living above his shop. By the time he retired at the turn of the century, he had moved his residence away from the tannery and built several new homes in the city as rental income and investment properties. And rather than training under their father in preparation to take over his business, Meredith’s sons attended university and became professional men. Jonathan’s wife, unlike Jane Baker, contributed to the family’s affluence, which in turn created the opportunity for their children to become professionals and entrepreneurs. Elizabeth Meredith kept the tannery books, supervised apprentices, and cared for boarders and her household. Her economic activity enabled her daughters to attend the Philadelphia Young Ladies’ Academy and to socialize with other young men and women from middling and elite families. It also meant that the Merediths, should they have needed it, had a financial safety net that the Bakers lacked.10

With hindsight, Ann knew that her mother should have been similarly occupied. The problem lay with Captain Baker’s social aspirations. A sea captain was on a par economically with a successful currier or shipbuilder, not a merchant or a lawyer. But Thomas Baker believed his family was socially on a level with families above the Bakers in terms of wealth. He also believed it was inappropriate for his daughters to work. Ann recalled that her father’s pride forbade “the idea of his daughters’ learning any trade.”11 The Bakers lived up to, and beyond, their means with no way of recovering when financial disaster struck. Ann’s wishful thinking may have been prompted by the fact that as a child and an adult she was surrounded by economically unreliable men: her father, her husband, and even two of her brothers-in-law, Thomas Abbott and Joseph Hutton. Ann saw in her mother’s life, her own life, and her sisters’ lives the consequences for women of overdependence on male breadwinners. Thus, in her autobiography, Ann advocated, like her contemporary Judith Sargent Murray, that young women be more than just ornamental.12 They needed skills to enable them to contribute to the family income.

The Baker family moved from Philadelphia to New Castle, Delaware, during Thomas’s West Indian employment. When he was invalided out of the navy in 1801, the family remained in New Castle for a time. There, Ann, fifteen years old, and her elder sister Eliza, seventeen, attracted the attention of several eligible naval officers. Eliza soon became engaged to a Captain Hillyard, commander of the sloop of war Pickering. Ann drew the attention of the Pickering’s purser, Mr. Willock, who asked Ann’s parents for permission to marry her. With such precarious finances, her parents readily agreed: “He was rich, and his situation lucrative, which at once conciliated [Jane Baker’s] good will; nor had my father any objection to make to the proposed alliance. Mr. Willock was therefore received as my destined husband by the family.”13 Unfortunately, Ann’s and Eliza’s happiness was cut short when the Pickering was lost at sea with all hands. Soon after this tragedy the Bakers moved back to Philadelphia. Despite Captain Baker’s desire to keep his wife from working, Jane Baker took eight boarders into their home on Dock Street.14

This reversal of the family’s fortunes in the late 1790s made marrying off their oldest daughters an attractive proposition. Eliza, after mourning the loss of Captain Hillyard, became engaged to John Hutton, the eldest son of a neighboring family. Ann, after her introduction to male society in New Castle, and her flirtation with Willock, attracted the attention of another naval officer, John Carson. The twenty-four-year-old Carson had been second lieutenant under Baker on the Delaware (Carson had also contracted yellow fever on the disastrous voyage to Curacao). Perhaps out of financial desperation, the prospect of removing two children from the Baker household compelled Thomas Baker to listen to John Carson’s request to marry fifteen-year-old Ann. As Ann understood it, her father’s affectionate attachment to Carson, whom he “loved … as a son, having participated in each other’s afflictions, and endured the dark hour of adversity together,” combined with Baker’s “imbecility of mind,” persuaded Baker to agree to the marriage. As to Ann’s feelings about this life-changing event, she described Carson in the following terms: “He was ever uniformly allowed to be a handsome man, his natural advantages were increased by his naval uniform, and a certain air of command which I had ever admired, as well as his dashing appearance.”15 As to Ann’s emotions at the prospect of marriage, she later claimed that “to the tender affection that ought to be the basis of all matrimonial engagements, my heart was an entire stranger.”16 This is hardly surprising given her age and her minimal contact with someone who was her father’s colleague, an adult nine years her senior.

What attracted Carson to a fifteen-year-old girl? Ann described herself as taller than the average woman and physically mature by the age of fourteen. Though, as she admitted, “This rapid growth gave me the appearance of womanhood, before age justified the idea, or my understanding was sufficiently cultivated to render me a suitable companion for gentlemen of my father’s standing in society and profession.”17 Ann, as the daughter of a sailor, could readily adapt to the peripatetic lifestyle of a spouse who would be away from home for long periods of time. The Bakers’ residence in New Castle after her father’s illness was Ann’s first introduction to male society. There she was “surrounded by gay, gallant, dissipated officers from all the states in the union, some of whom vied with each other to gain my approbation and favour. Thus were the seeds of vanity and the love of conquest cherished in my heart.”18

By her own admission, Ann found naval men more attractive than those of any other profession: “Sea-faring men are generally possessed of strong minds and extended ideas; their profession carrying them to every quarter of the globe, and the extensive intercourse they have with persons of all ranks of society, gives a liberality to their minds which few, if any other class of men ever acquire. This, united to their education and habits of command, gives them a superiority over landmen.”19 John Carson was such a man. He was handsome, came from a good family (his father had been a prominent Philadelphia physician), and he was a college-educated naval officer on the fast track to promotion and financial success. John Carson’s income and social background could restore Ann to her comfortable middle-class world.

Ann Baker married John Carson in June 1801. The following month, John departed for India, working as chief officer on the ship China. John Carson may have chosen to leave the navy at this time to earn a larger income in the private sector. Whatever his reason, he sought work as a master on merchant ships in both the East India and China trade for the next six years. Ann moved in with her parents. When John came back from the East Indies, the couple set up a house, “furnished in a genteel manner,” at 47 George Street in Southwark, a few blocks from the river.20 Ann later returned to her parents’ home when she was pregnant with her first child. This was her pattern over the next several years: residing with her husband between voyages and staying with her parents during John’s absences.

In 1804, John Carson assumed command of the Pennsylvania Packet, owned by Joshua and Thomas Gilpin. Carson made voyages to Madras and Calcutta in May of that year and then sailed to Canton in June 1805.21 Ann Carson was materially well cared for during these years. Her time was spent rearing a growing family (they had three sons between 1803 and 1811). Financially, John’s position as a ship captain provided the Carsons with a comfortable income. Moreover, and of importance to Ann’s economic future, John took advantage of his visits to the East to purchase quantities of porcelain—an investment as well as an enhancement to the family’s lifestyle.

But Captain Carson’s trip to China was not without incident. The Pennsylvania Packet arrived in Canton loaded with ginseng, a commodity much in demand by the Chinese. According to Ann’s account of the misadventure that followed, John, against his better judgment, was persuaded by an unnamed gentleman—probably the supercargo—to sell some of the shipment illegally. Disaster ensued. John Carson himself was only indirectly involved, as the laws of the port of Canton required foreign ships to anchor at Whampoa, four miles down the Pearl River from the city. Only small boats that ferried the cargo into Canton were allowed back and forth between the sailing ships and the warehouses on the docks.22 The Pennsylvania Packet’s supercargo was responsible for conducting business ...