![]() Part I

Part I

Introduction![]()

Chapter 1

Somalia from the Margins: An Alternative Approach

A letter arrives, telling me that every child under the age of five was now dead in the Jubba valley village in southern Somalia where I had lived several years previously. The collapse of the Somali state in 1991 ended these young lives in starvation and warfare, opening yet another violent chapter in the short history of the Jubba valley. In just the past 150 years, the people of this valley—most of whom were considered racial minorities within the Somali nation-state—had endured a series of violent encounters that shaped their relationship to the state and to regional Somali society. Such encounters—including enslavement, forced labor on colonial plantations, periodic pastoralist raids, kidnapping by the state military, and forceful land dispossession in the biggest political landgrab in Somali history—presaged their vulnerability in the violence of civil war. When the Somali state collapsed, the people of the Jubba valley disproportionately faced genocidal assault, banditry, and widespread rape. Although the valley’s population has been massively reduced through starvation, murder, and flight since 1991, the valley remains one of the most contested areas in the militia wars that continue to plague southern Somalia.

How does a place become so violent? In 1991, journalists, pundits, politicians, and academics groped for metaphors that could simply and concisely explain the warfare. The most persistent and pervasive explanation knit together popular perceptions of “tribalist” Africa with models derived from anthropological descriptions of northern Somali social groups to claim that “ancestral clan hatreds” played out in warfare both caused Somalia’s collapse and hindered future state-building efforts. Since I. M. Lewis’s (1961) classic book on northern Somali pastoralist social organization first appeared, Somali society has usually been described in academic and popular literature as an egalitarian and ethnically homogenous population of nomadic pastoralists who shared an overarching genealogical system and a common language, culture, and religion. Lewis described Somali society as consisting of six patrilineal clan-families formed by the descendants of mythical Arabic ancestors who arrived in Somalia twenty-five to thirty generations ago. His pioneering work on Somalia explained that each clan-family encompassed a set of patrilineally related clans, subclans, sub-subclans, and lineages. Historically, political activity usually occurred at the level of lineages or groups of lineages tied together by social contracts who collectively paid diya, or blood compensation, for wrongs committed by any group member. While clan-families rarely acted as a unit, diya-paying groups and lineages could join forces at higher levels against other groups of lineages for warfare and payment of diya.

Drawing upon this model (called a segmentary lineage structure by specialists), the American media and some academic accounts of Somalia’s collapse presented Somalia’s destruction as having been almost inevitable. The model of the tensions inherent to this kind of genealogically based system provided an explanation of built-in conflict, making Somali social structure appear fundamentally divisive and resistant to state-building efforts. Journalists’ reports portrayed Somalis as continuing to act out Stone Age ancestral clan rivalries, but with Star Wars military technology. Media reports were filled with evocations of ancestral violence: “The clans of Somalia have regularly battled one another into a state of anarchy” (Time 1992); “ancient clan enmity pursued with the modern weapons that are so abundant in Somalia is at the root of the country’s conflict” (Washington Post 1993); “Instead of fighting with traditional spears and shields, the clans have more recently conducted their feuds with mortars and machine guns” (New York Times 1992); “the crisis in Somalia has been caused by intense clan rivalries, a problem common in Africa, but here carried out with such violence, there is nothing left of civil society, only anarchy and the rule of the gun” (CNN 1992).1 In refashioning academic terminology to present a portrait of Somalia’s collapse, Somalis became cartoon-like images of primordial man: unable to break out of their destructive spiral of ancient clan rivalries, loyalties, and bloodshed.

This book challenges the prevailing explanation that the violent breakdown of Somali civil and political society was the result of deep clan-based hatreds and ethnic loyalties. Most specifically, it argues that this explanation is inadequate for understanding the most violent areas of contemporary Somalia, such as the Jubba River valley. Taking the Jubba valley as my focus, I suggest that the dissolution of the Somali nation-state can be understood only by analyzing the turbulent history of race, class, and regional dynamics over the past century and a half—processes which produced a deeply stratified and fragmented society. Over the past several generations a social order emerged in Somalia that was rooted in principles other than just a simple segmentary lineage organization—a social order stratified on the basis of racialized status, regional identities, and control of valuable resources and markets. To understand the 1990s breakdown of the Somali nation-state—and the particular victimization of agricultural southerners during and after dissolution—one must acknowledge the basis and significance of these alternative forms of stratification.

By focusing on one particular community on the margins of Somali society and the Somali nation-state—the people of the Gosha area of the middle Jubba River valley—this book probes the tensions produced by these alternative forms of stratification. I will be looking beyond the fantasy of an ethnically and linguistically homogenous culture to illuminate some of the other critical fracturing points of Somali society. Such fracturing points—of race, class, and region, as well as status, occupation, and language—become clearer when we turn our focus away from the urban elite politics of the center that have dominated both media coverage and scholarly analyses. Scrutinizing the history of the margins can magnify the primary processes shaping the center; looking at state disintegration from the margins of the Jubba valley reveals the dynamism of Somali society (which is left uncaptured in the segmentary lineage model) in general, and illuminates the tense dynamics of racialized identities and stratification, in particular, which were central to state formation in Somalia and which patterned much of the violence of disintegration.

While aiming to illuminate some critical aspects of the state, this book is not an ethnography of the state, of state-building, or of state-collapse; rather it is an ethnography of the local, situated at the margins of the state. Nevertheless, one of my goals is to use the view from the margins to apprehend the institutions, discourses, and forces of the state as well as the tensions and frictions which contributed to the state’s collapse. As Michael J. Watts has argued, localities “are always political and struggled over,” a fact which allows us to see “locality as a fundamental part of national identity and hence a repository of various rights and memberships that are regularly spoilt and fought over” (1992:121).2 Looking at the expression of the state on the margins and the way people on the margins experience and imagine the state can, I believe, illuminate its structures of domination, its technologies of power, the effectiveness of its discourses, the nature of its hegemonic representations, and the extent of its popular support. As James Scott has noted, referring to analyses of state collapses: “And whenever . . . the ship of state runs aground on such reefs, attention is usually directed to the shipwreck itself and not to the vast aggregation of petty acts that made it possible” (1985:36). Focusing on the local—where we can perhaps best see the vast aggregation of petty acts—is still, I believe, what anthropologists do best, and what we do better than any other discipline: we can use these strengths of local-level ethnography to analyze and theorize the state.

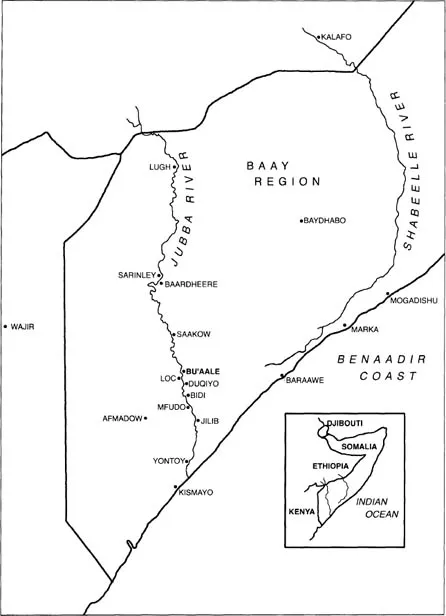

Map 1. The Jubba valley of southern Somalia.

Some of the major processes that have shaped Somali society and defined its power dynamics are inscribed in the marginal space of the Jubba valley and in the historical experiences of the people who live there. Over the past 150 years, the Jubba valley (Map 1) has been imaginatively constructed and ecologically utilized in a variety of ways by the people who live there, by the Somali national community, by the state, and by foreign authorities and donors. The valley has alternatively been viewed as a refuge, as a frontier, as a dangerous place of magic and sorcery, as a place of fantastic agricultural potential, as a desolate backwater, as a national ecological resource, and, most recently, as one of the premier “shatter zones” and valuable prizes in Somalia’s civil war. The Jubba valley in the mid-1990s has been the site of massacres, of famine, of years of militia wars, and of a disproportionate outpouring of the surviving local farmers into refugee camps; many of the faces shown on television screens depicting Somalia’s tragedy belong to people from the valley. The valley has now emerged as one of the most significant areas of contention, ending a century (or beginning a new century) of land occupation, expropriation, and development plans carried out by colonial governments, by the Somali state, and by international donor agencies.

The people of the Gosha have participated in, been subjected to, supported, and struggled with the significant cultural, political, and economic changes sweeping through the Horn of Africa in the past century. Their ancestors, taken from the area stretching between contemporary Kenya to Mozambique, arrived in Somalia in the nineteenth century as slaves to work on Somali-owned plantations producing cash crops for export. After escaping as fugitives or being manumitted as Muslim converts, these former slaves settled the uninhabited forests of the Jubba River valley. Twentieth-century Gosha history reflects key elements of the national experience: Gosha communities had their land taken over by colonial plantations and their bodies claimed for colonial forced-labor schemes, they lost complete rights to their land through socialist-inspired nationalization laws after independence, experienced the speculatory effects of a 1980s capitalist-inspired commodification of land, and suffered from phenomenal Cold War-linked state militarization. Although discriminated against as a racial minority on the basis of their “Bantu” heritage since their arrival in Somalia, Gosha people have throughout this tumultuous history continuously struggled to define their identity and a legitimate place within Somali society, using Islam, kinship, and economic relations as their tools.

The historical experience of the people living in the Gosha brings into relief the critical significance of racial and growing class distinctions in Somali society during the twentieth century. Because their status as racial minorities took precedence over their lineage and clan affiliations, the Gosha peoples’ history offers a window into the ways that Somali society was stratified by constructions other than clan. Their increasing economic marginalization reveals the basis of emerging class stratification in southern Somali society during this century. By tracing historically the creation of “the Gosha” as a large, subordinate (and disparate) group in southern Somalia, this study highlights the problematic and contingent nature of “ethnic consciousness,” identity politics, and class formation. Trying to understand the brutal victimization of Gosha farmers since 1991 highlights the tragic cultural logic informing race, class, and regional dynamics in contemporary Somalia.3

Despite its often chaotic appearance, violence is never simply anarchic, but rather is informed by a particular logic and a sense of purpose. “For analysts of specific cultures and places,” suggests Kay Warren, “the imperative is to dispel the view that violence is inherently chaotic and irrational by tracing the implications of particular forms of domination, resistance, and violence” (1993a:3). Also invoking culture and history—and thereby challenging anthropologists—Fernando Coronil and Julie Skurski (1991) argue that political violence can be understood only by attending to the specific historical context of social relations, cultural forms, and memory in violent places.4 While we may lack the ability to “explain” the ruthlessness of violence, people participating in violence often do have at least a momentary sense of what they’re doing. What appears senseless is often informed by a particular sensibility that emerges in particular historically conditioned moments and is shaped by particular cultural practices and ideologies. While the act of violence may remain ultimately unapprehendable, we can seek to understand the historical and cultural tensions that surround that act and provide it with meaning. Although this book is not an ethnography of Somalia’s disintegration, taking a good look at some of the heretofore relatively masked aspects of cultural and social stratification in Somalia will, I hope, take us part of the way toward a better understanding of the historically produced social relations that have patterned much of the postcollapse violence in southern Somalia.

This book also examines the thorny problem of how to understand the widely experienced simultaneity of domination and resistance, subjugation and collusion. Analyzing Gosha peoples’ historical experiences illuminates the position of subjugated peoples living within structures of domination which define the hegemonic terrain of morality, social identity, and appropriation. This book attempts to interrogate history in order to understand how an ideology of hierarchy which assigned a denigrated, subordinate status for Gosha peoples was constructed and symbolically represented, morally legitimized, and materially enacted in Somali culture and society. Apprehending the structures of domination also means recognizing the contours of collusion: how people in the Gosha simultaneously resisted the ideological basis of denigration—which subjugated them as “slaves,” “Bantus,” and low status farmers—while accepting as legitimate the hegemonic Somali social order based on kinship.

As I will argue below, despite their denigrated position within Somali society most Gosha people did not view themselves as any kind of recognizable ethnic group set on a course of resistance against the society that denigrated them. To the contrary, rather than fostering a group sense of cultural distinctiveness and subjugation, most Gosha villagers oriented their cultural practices and identity politics toward dominant Somali patterns. A central question of this book is how to understand Gosha peoples’ choices to participate within and actively seek incorporation into a society which subjugated them, and how to understand their creative ability to manage the juxtaposition of domination and accommodation.

Gosha peoples’ historical experiences firmly situated them at the intersection of racial hierarchies, class stratification, the hegemonic Somali kinship system, and state politics—a tension-filled space within which they negotiated a personal politics of identity, culture, and social relations. Understanding this space, which will occupy us in Part III, reveals the mutually constitutive dimensions of culture, identity, and politics. Seeing in Gosha experiences the processes of nation-building and state dissolution in Somalia, we can probe the critical links between cultural struggle, identity politics, class, and the state that exists throughout Africa.

For decades, anthropologists have grappled with the concept of identity, as we have argued over how to define it, how to identify it, where to locate it (assuming it is a single entity, which we cannot). Responses to these questions have variably addressed the political and cultural dimensions of identity, usually reformulated as ethnicity. The 1970s and 1980s marked a turn in our disciplinary approach to studying ethnicity/identity, when anthropologists began rejecting earlier assumptions of cultural/ethnic primordialism/essentialism to emphasize instead the fluid and situational aspects of ethnic identity, where people made choices about their ethnic identities in different sociopolitical contexts.5 While transformative for the understanding of identity formation, this situational or constructionist approach often lacked sufficient attention to the role of political struggle and state-formation in setting constraints, delimiting options, or defining the possible in the shaping of identity.6

The rise of a political economy focus in anthropology in the late 1970s and early 1980s, together with a growing postcolonial acknowledgment of colonialism’s impact on our anthropological “subjects,” spawned a view of contemporary ethnicity/tribalism as the result of the political economy of colonial rule7—a realization first suggested by an earlier generation of anthropologists.8 Writing from a similar perspective influenced by political economy, others suggested contemporary forms of tribalism or ethnicity resulted from violent warfare in the context of European expansion.9 Applying the lens of political economy has allowed some scholars to explain local forms of ethnicity as a creation of global capitalism played out in local contexts through labor relations,10 or to emphasize how the semantics of primordial sentiments are situationally used to generate ethnic cohesion in the context of warfare, violent competition, and global capitalism.11 Most recently, scholars have highlighted the role of the postcolonial state in directly fostering ethnic identities and ethno-nationalisms through authoritarian rule, unequal distributions of resources...