- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Mourning Glory sheds light on troubled times as it shows how passion and prejudice, grief and denial all contributed to the continuing creation of a revolutionary legacy that still affects our understanding of the nature of language and history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mourning Glory by Marie-Hélène Huet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & French History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

INTENTS AND PURPOSES

1

Political Science

IN 1756, UNDER THE ARTICLE Thunder, Diderot’s Encyclopedia provided the following information on how to protect oneself from thunderbolts:

The thunderbolt can be broken up or turned away by the sound of several large bells or by shooting a cannon; this stimulates in the air a great agitation that disperses the thunderbolt into separate parts; but it is essential to take care not to toll the bells when the cloud is directly overhead, for then the cloud may split and drop its thunderbolt. In 1718, lightning struck twenty-four churches in lower Brittany, in the coastal region extending from Landerneau to Saint-Pol de Léon; it struck precisely those churches where the bells were tolling to drive it away; neighboring churches where bells were not tolling were spared.1

This text points out the two principles that simultaneously mediate and limit the power conferred by human knowledge: the church, and the essentially whimsical character of nature. The bells that tolled in the hope of turning away the lightning, a modest scientific experiment, brought upon themselves the fire of the gods with uncanny precision and devastating magnitude. The exercise of knowledge—that the sound of bells drives lightning away—is here immediately punished, on an almost divine scale, destroying moreover the very churches humans had constructed for their worship of God. By contrast, the silent steeples remain unscathed, spared by the furious storm, a paradoxical metaphor for a religious and ignorant people, unconcerned with understanding the fire from Heaven, forever resigned and gloriously rewarded for their blind submission.

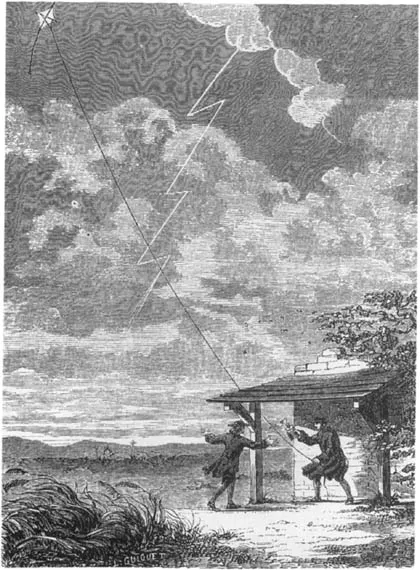

This article from the Encyclopedia obviously did not take account of the theories on lightning first published by Benjamin Franklin in London in 1751 under the title Experiments and Observations on Electricity.2 Preliminary application of Franklin’s theories would come a year later and take various forms, such as the kite or the “fulminating bars” of François Thomas Dalibard in France. The 1777 Supplement to the Encyclopedia, however, did full justice to Franklin’s invention and ingenuity. A second Thunder article was written, and the text read as follows:

It is a truth now recognized by all physicists that the matter which flames up in clouds, which produces lightning and thunderbolts, is nothing other than electric fire; the famous Franklin assembled the proofs of this in his fifth letter on electricity. . . . M. Franklin proposed as early as 1750 to use these means [electric kites, fulminating bars, and other sorts of apparatus] to protect buildings and ships from lightning; observations have proven so successful that it is now of interest to explain, in a way everyone can understand, how to build these conductors or lightning rods.3

Dismissing the fallen steeples of the Brittany coast, the author gave as examples of enlightened technology an imposing list of individuals and institutions that had successfully installed lightning rods on their roofs. The article’s author was none other than Louis-Bernard Guyton-Morveau, a distinguished chemist who was later to play an active role in the French Revolution.4 However, it would be a long time before the Encyclopedia’s conclusive pronouncements on lightning and thunder would be accepted.

In 1780, Monsieur de Vissery de Bois-Valé, a lawyer from Saint-Omer, a town in northern France, installed a lightning rod on his roof. His frightened neighbors sought redress, convinced that the lightning rod, like the tolling bells of Saint-Pol de Léon, was more likely to attract bolts that would strike them dead than to protect them from the storm. On 14 June 1780, the magistrates of Saint-Omer, siding with the concerned population, ordered the lightning rod removed within twenty-four hours. On 16 June Monsieur de Vissery submitted to the court a petition “accompanied by a special report, the object of which was to furnish the judges with a complete demonstration of the electrical machine placed above his house.”5 Arguments were heard on 21 June, and Monsieur de Vissery’s petition to keep the lightning rod was denied. Two days later, he appealed to the Artois Council, after agreeing in the interval to dismantle the apparatus so distressing to the population. In fact, he did nothing more than remove the sword blade that was the most visible part and substitute a shorter blade. And, so that no one should see even this concession as a signifying abasement of the ruling class symbolized by the sword, Vissery confided to his lawyer, “This is how to deal with the ignorant masses.”6

Figure 1. Benjamin Franklin’s experiments with an electric kite, 1752. Engraving. Collection Viollet.

Monsieur de Vissery entrusted the affair to Antoine-Joseph Buissart,7 then a member of the Arras and Dijon Academies, who regularly contributed to the Journal de Physique. Buissart took the affair to heart, and interminable consultations took place throughout France. The man slowest to answer Buissart’s repeated requests for scientific data was Jean-Antoine-Nicolas Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet, who eventually let it be known that, speaking in his capacity as perpetual secretary of the Academy of Sciences, he considered the best defense to be a detailed and documented report containing all the scientific arguments in favor of the lightning rod. Buissart went to work and published his report in 1782. The Appeal reached the Council of Artois in May of 1783, when Buissart gave Maximilien Robespierre, then a very young lawyer, the task of representing to the Court the combined interest of science and Monsieur de Vissery.

The trial, which aroused passing but intense interest, is revealing not only because it brought together, some years before the Revolution, the names of Marat, Condorcet, Franklin, and Robespierre, but also because it sparked a debate on Enlightenment and religion, science and human progress, that was to continue until Robespierre’s death, near the close of the Revolution, in July 1794.8

The party fiercely opposed to the lightning rod invoked the authority of two learned men, one of whom was none other than Jean-Paul Marat, the future “Ami du peuple.” The Abbé Bertholon, himself an eminent physicist, wrote Buissart that Marat was “a crazy man who thought he could become famous by attacking great men and producing paradoxes that seduced no one.” But, undeterred by critics, Marat in his Recherches physiques sur l’électricité had noted: “It is obvious that the fluid accumulated in clouds is beyond the sphere of attraction of the highest conductor.” He also enumerated eleven cases of conductors “blasted by lightning.”9

In response, Robespierre made two speeches that took their scientific content, their examples, and a part of their logic from the work to which Buissart had devoted two years. Yet the final formulation is that of the young lawyer who published his two discourses under the title Arguments for the Sieur de Vissery de Bois-Valé, appealing a judgement of the magistrates of Saint-Omer, who had ordered that a lightning rod erected on his house be destroyed.10 Robespierre’s argument was persuasive; the Council of Artois found in favor of his client, Monsieur de Vissery. Emboldened by this success, Robespierre sent a copy of his argument to Franklin himself, along with a letter that, although often quoted, deserves another hearing. It is dated 1 October 1783, four months after its author’s striking success. Robespierre wrote:

Sir,

A writ of condemnation by the magistrates of Saint-Omer against electrical conductors furnished me the opportunity to appear before the Council of Artois and plead the cause of a sublime discovery for which the human race owes you its thanks. The desire to help root out the prejudices that opposed its extension in our province led me to publish the speeches I made during this affair. I dare hope, Sir, that you will deign to have the goodness to accept a copy of this work, the object of which was to induce my fellow citizens to accept one of your gifts: happy to have been useful to my country by persuading its first magistrates to welcome this important discovery; happier still if I can add to this advantage that of being honored by the good graces of a man whose least merit is to be the most illustrious scientist of the universe. I have the honor of being with respect, Sir, your most humble and obedient servant.11

In the France of the 1780s, Franklin’s glory was at its apogee. He was the man of the lightning rod and of the American Revolution, a double achievement Turgot12 captured in a Latin epigram that spread among the Paris salons: “Eripuit coelo fulmen, sceptrumque tyrannis.”13 This epigram became tremendously popular. It appeared in 1778 beneath the bust of Franklin sculpted by Jean-Baptiste Houdon, and it was the beginning of countless poetic essays—of unequal merit—dedicated to the glory of the American scientist and politician. In an exchange of letters between d’Alembert and Jean-Baptiste Suard, the encyclopedist undertook to translate Turgot’s epigram and hesitated between two possible versions. D’Alembert first wrote:

Figure 2. Portrait of Benjamin Franklin. Engraving by Labadye. Collection Viollet.

Tu vois le sage courageux / Dont l’heureux et mâle génie / Arracha le tonnerre aux dieux / Et le sceptre à la tyrannie. (See the brave and wise man / Whose happy and male genius / Wrested thunder from the gods / And the scepter from tyranny.)

D’Alembert reflected that one might say that Franklin wrestled lightning either from the skies or from the gods, aux cieux or au dieux (p. 128). This literary and philosophical hesitation, as to whether the conquest of lightning is a victory over nature or a more Promethean triumph over a sacred principle, echoes in fact the two Thunder articles in the Encyclopedia. They both emphasize the fact that all knowledge is a seizure of power, a challenge, a deed of the same stamp as a political revolution. Turgot’s epigram, d’Alembert’s double translation, and the Saint-Omer trial form an ideological nexus structured by the Enlightenment’s connection to science as well as the Enlightenment’s contribution to the Revolution. In these heated and often contradictory debates, a recurrent series of metaphors put lightning and enlightenment into serious play.

Scientific Laws

In a work entitled Clartés et ombres au siècle des Lumières,14 Roland Mortier traces the history of the philosophical meaning of the word lumières from Genesis to Kant’s celebrated Was ist Aufklärung? He notes, in particular, that the use of lumières was secularized in the seventeenth century.15 The metaphor of Enlightenment as reasoned knowledge would become general in the eighteenth century. The Encyclopedia provided the metaphor’s richest field of expression. Here, far from being associated with knowledge of a religious nature, Enlightenment was directly opposed to all knowledge transmitted, or authorized, in the strict sense of the term, by the church. Diderot contrasted an “enlightened century” to “times of darkness and ignorance” (p. 30). Voltaire complained that “a Gothic government had snuffed out all enlightenment for almost 1200 years” and D’Alembert congratulated himself that “enlightenment has prevailed in France” (p. 31).16

His legal arguments on the lightning rod gave Robespierre the opportunity to develop his own version of the familiar metaphor of Enlightenment. Ridiculing his opponents, he proclaimed, “How dangerous to want to enlighten one’s fellow citizens! Ignorance, prejudices and passions have formed an awesome front against men of genius, in order to punish them for the good they do their fellows.” Elsewhere, Robespierre celebrated “the progress of enlightenment,” “enlightened nations,” “the torch of the arts,” and “the torch of true principles.”17

More important, the physical description of lightning and thunderbolts served as a privileged illustration of the complex relationship between Enlightenment and nature. Indeed, lightning is the prime example of a power without reason that strikes blindly, by pure chance.18 Lightning is disorder in nature, prompting Robespierre to describe Franklin’s discovery as a step toward correcting both anarchical violence and unreason. Thanks to the lightning rod, “Lightning accepted its laws and thereby immediately lost this blind and irresistible impulse to strike, smash, overturn, crash all that stands in its way; it has learned to recognize the objects it is to spare.”19 In other terms, and this may be the most interesting part of this description, Franklin has not so much discovered a scientific law as imposed on nature a law made possible by scientific knowledge. Nature—a blind force that destroys indiscriminately—is arraisonnée, that is, conquered, put to reason. It is for the true Enlightenment to tame this energy and submit nature to its laws. Robespierre sets out to demonstrate simultaneously—here he is in no way Rousseau’s disciple20—the savage, crude, and noxious character of untamed nature, and in contrast the purely beneficent powers of science and reason. To illustrate the lightning rod’s virtues, Robespierre compares it to inoculation, itself far from unanimously accepted by scientists. “We must calculate,” he said, “the victims art has saved, and those nature has sacrificed; but, because this calculation generally proved that men gain more from confiding themselves to art than from giving themselves to nature, inoculation has triumphed over all obstacles.”21

In the opposition he was powerfully drawing between Enlightenment and nature, Robespierre demystified the idea of an inspired nature, the manifestation of a benevolent and hidden God whose secrets were forever closed to humanity. Did this mean that science took the place of a deposed God? Not in the least; and this is perhaps the most curious point in Robespierre’s arguments: humans must no more let themselves be dazzled by science than by the lightning that threatens to strike them dead. This is in fact the lawyer’s most extensively developed theme. Conflating at one point the power of Enlightenment and the conquest of the Americas, Robespierre exclaimed:

The Enlightened European had become a God for the savage inhabitants of America; I call those peoples as witness, for they gave no other name to their conquerors. Were they so very wrong? Was not lightning in the hands of these terrible warriors? Was not their arrival in those unknown regions a prodigious deed accomplished to justify such an idea? And, whet...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Revolutionary Will

- Part I. Intents and Purposes

- Part II. Last Will and Testament

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index