![]()

PART I

Native Power and European Trade

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Tsenacomoco and the Atlantic World: Stories of Goods and Power

In what might be the only surviving early seventeenth-century example of the genre, William Strachey, secretary of the Virginia Company of London, did his best to reduce to Roman letters a “scornefull song” that victorious Powhatan warriors chanted after they killed three or four Englishmen “and tooke one Symon Score a saylor and one Cob a boy prisoners” in 1611:

1. Mattanerew shashashewaw crawango pechecoma Whe Tassantassa inoshashaw yehockan pocosak Whe, whe, yah, ha, ha, ne, he wittowa, wittowa.

2. Mattanerew shashashewaw, erawango pechecoma Captain Newport inoshashaw neir in hoc nantion matassan Whe weh, yah, ha, ha, etc.

3. Mattanerew shashashewaw erowango pechecoma Thomas Newport inoshashaw neir in hoc nantion monocock Whe whe etc.

4. Mattanerew shushashewaw erowango pechecoma Pockin Simon moshasha mingon nantian Tamahuck Whe whe, etc.

Strachey explained that the refrain—which almost needs no translation—mocked the “lamentation our people made” for the deaths and captivities. But far more interesting is the gloss he provided for the verses. The Powhatans sang of “how they killed us for all our Poccasacks, that is our Guns, and for all Captain [Christopher] Newport brought them Copper and could hurt Thomas Newport (a boy whose name indeed is Thomas Savadge, whome Captain Newport leaving with Powhatan to learne the Language, at what tyme he presented the said Powhatan with a copper Crowne and other guifts from his Majestie, sayd he was his soone) for all his Monnacock that is his bright Sword, and how they could take Symon … Prysoner for all his Tamahauke, that is his Hatchett.”1 In spite of all their material goods—their guns, their copper, their swords, their hatchets—and in spite of the fact that many of these same vaunted items had been given to the Powhatans by Virginia’s leader Newport in the name of the mighty King James, the Englishmen had, at least on this occasion, been made subject to Native people’s power.2

Like the song, this essay is a story about goods and power. Or, rather, it is three related stories about Chesapeake Algonquian men and what appear to have been their quests for goods and power from the emerging Atlantic world of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries: Paquiquineo (Don Luis), who probably left the Chesapeake in 1561 and returned with a party of Spanish Jesuit missionaries nine years later; Namontack, who traveled to England with Christopher Newport in 1608 and again in 1609 (while the Thomas “Newport” Savage of the song took up residence in Powhatan country); and Uttamatomakkin (also known as Tomocomo or Tomakin), who made the oceanic voyage with Pocahontas in 1616–1617. We know very little about any of these men, their status, or their motives, and what we do know comes down to us in highly colored tales written by Europeans who were not exactly their friends. Nonetheless, for all the dangers of skimpy sources, of European chroniclers’ distortions, and, possibly, of an overactive historian’s imagination, the stories deserve serious attention. Traveling at particularly crucial moments in their people’s early engagement with Europeans, the three voyagers allow us to glimpse something of what the emerging Atlantic world meant to the elite of the Powhatan paramount chiefdom—if not to the common people who gave their “densely inhabited land” its name, Tsenacomoco. In their travels, Paquiquineo and Namontack apparently attempted to exert control over the access to the goods the 1611 song would mock in order to build up the power of their people, their political superiors, and themselves. Uttamatomakkin’s travels, by contrast, confirmed what the singers by then already knew: that power would have to be asserted in spite of, not by way of, “guifts from his Majestie.”

* * *

Just as the arrival of Spaniards and English in the Chesapeake cannot be understood apart from the political and economic characteristics of competitive Early Modern nation-states, the exploits of these three voyagers from Tsenacomoco—and the significance of material goods in the Powhatan song—cannot be understood apart from the political and economic characteristics of the social forms known as chiefdoms. In the classic definition of anthropologist Elman R. Service, “chiefdoms are redistributional societies with a permanent central agency of coordination” and a “profoundly inegalitarian” political order in which redistributive functions center on exalted hereditary leaders.3 For Service and his contemporary Morton Fried, the material underpinnings of stratified chiefdoms lay in “differential rights of access to basic resources … either directly (air, water, and food) or indirectly,” through the control of such basic productive resources as “land, raw materials for tools, water for irrigation, and materials to build a shelter.” More recent comparative archaeological work, however, moves beyond such straightforward materialist definitions to embrace a much more complex variety of cultural forms.4

Much of this work roots chiefdoms in what is known as a “prestige-goods economy.” As archaeologists Susan Frankenstein and Michael Rowlands explain, in such an economy, “political advantage [is] gained through exercising control over access to resources that can only be obtained through external trade.” These resources are not the kind of basic utilitarian items described by Service and Fried but instead “wealth objects needed in social transactions.”5 They may be, as anthropologist Mary Helms explains, “crafted items acquired ready-made from geographically distant places” or things “valued in their natural, unworked form as inherently endowed with qualitative worth—animal pelts, shells, feathers, and the like.” In either case, they “constitute a type of inalienable wealth, meaning they are goods that cannot be conceptually separated from their place or condition of origin but always relate whoever possesses them to that place or condition.” The social power of such goods thus comes from their association with their source, often described as “primordial ancestral beings—creator deities, culture-heroes, primordial powers—that are credited with having first created or crafted the world, its creatures, its peoples, and their cultural skills.” Indeed, inalienable goods never fully belong to those to whom they have been given; they always remain in some sense the property of the giver. Those who control such prestige goods wield power because of their connection to—and control over—power at the goods’ source.6

In eastern North America, the prestige goods that shaped the power of chiefdoms were the crystals, minerals, copper, shells, and mysteriously crafted ritual items that moved through the ancient trade routes of the continent. Their potency came from their rarity and their association with distant sources of spiritual power. But those same characteristics made eastern North America’s prestige-goods chiefdoms inherently unstable political forms. Lacking a monopoly of force to defend their privileges, chiefs depended for their status on a fragile ideological consensus at home and on equally fragile external sources of supply and trade routes they could not directly control. Chiefdoms thus perched on a fine line between slipping “back” into less hierarchical forms or moving “forward” toward the coercive apparatus of a state while “cycling” between periods of centralization and decentralization. As a result, as social forms, they were forever in flux.7

The basic political units of late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Tsenacomoco were just such unstable prestige-goods chiefdoms, headed by men and women called, respectively, weroances and weroansquas, whose titles descended, as John Smith explained, to “the first heyres of the Sisters, and so successively the weomens heires.”8 Most of these local chiefdoms were subordinate to a larger paramount chiefdom that Powhatan, or Wahunsonacock, presided over as mamanatowick in the early seventeenth century. The weroances and particularly the mamanatowick owed their status in part to kinship, through their own matrilineages and through marriage alliances with the multiple spouses to which apparently only the elite were entitled. (Wahunsonacock reputedly had a hundred wives strategically placed in subordinate towns.) In a way Service and Fried would recognize, weroances also to some extent controlled food surpluses, through tribute from subordinates and through corn, bean, and squash fields their people planted and harvested to be stored in their granaries. (These food stores may have taken on additional significance during the repeated droughts and crop failures of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.) But most importantly, weroances’ power apparently rested on their control of such goods as copper from the continental interior and pearls from the Atlantic coast. As archaeologist Stephen R. Potter puts it, “chiefs handled worldly risks confronting their societies by serving as both a banker to their people and a culture broker to outsiders.”9

To a significant degree, the power that derived from these functions came from a weroance’s ability to distribute prestige goods to followers and thus create bonds of asymmetrical obligation. “He [who] perfourmes any remarkeable or valerous exployt in open act of Armes, or by Stratagem,” observed Strachey, “the king taking notice of the same, doth … solemnely reward him with some Present of Copper, or Chayne of Perle and Beades.”10 Lavish feasts from chiefly stores and perhaps the bestowal of sexual favors from young women in the weroance’s household served similar redistributive functions for diplomatic visitors.11 Such actions merged into a broader pattern that might best be described as the conspicuous display of chiefly power. Wahunsonacock “hath a house in which he keepeth his kind of Treasure, as skinnes, copper, pearle, and beades, which he storeth up against the time of his death and buriall,” wrote Smith. The structure was “50 or 60 yards in length, frequented only by Priestes,” and at each corner stood “Images as Sentinels, one of a Dragon, another a Beare, the 3[rd] like a Leopard and the fourth a giantlike man, all made evillfavordly according to their best workmanship.” Smith—who, it should be recalled, appeared to be an emissary from a strangely female-less society—also went out of his way to note that the mamanatowick “hath as many women as he will, whereof when hee lieth on his bed, one sitteth at his head, and another at his feet, but when he sitteth, one sitteth on his right hand and another on his left.”12

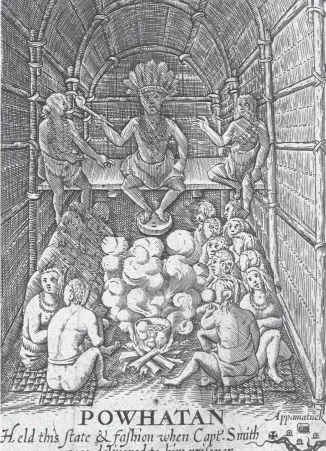

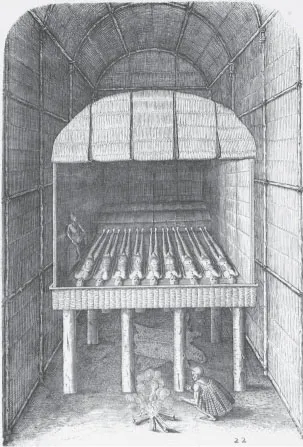

Illustrations from John Smith, A Map of Virginia … (London, 1612); and Thomas Hariot, A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia … (Frankfurt am Main, 1590). The fanciful image of Powhatan that graced William Hole’s engraving of John Smith’s 1612 map (left) is based on two engravings of watercolors painted by John White at Roanoke in 1585: an effigy of a spirit-being (top right) and the structure in which the bodies of deceased chiefs were preserved (bottom right). All of these images hint at the status and power that chiefs derived from what modern scholars call “prestige goods.” Reproduced by permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

Such conspicuous display embodied the strength and wealth of the people and their connection to the sources of the power that prestige goods and marriage connections represented; indeed, the term weroance roughly translates as “he is wealthy.”13 Such goods visibly accumulated at the apex of the social and political order, in the person regarded “not only as a king but as halfe a God,” the mamanatowick, a word incorporating the term manitou, or “spiritual power.”14 The material, the spiritual, and the political were inseparable in the person of the mamanatowick and the people for whom he acted. “The wealth of the chief and his distribution of it are alike means by which he confers life and prosperity on his people,” anthropologist Margaret Holmes Williamson explains. “Indeed, he really has nothing of ‘his own’ as a private person. Rather, he is the steward of the group’s wealth, deploying it on their behalf for their benefit.” The mamanatowick “by being rich and generous and by living richly … makes bountiful the macrocosm that he represents.”15

The material, the spiritual, and the political also came together in the fact that the vast majority of the powerful goods that chiefs accumulated were interred with them when they died. Weroances “bodies are first bowelled, then dryed upon hurdles till they bee verie dry, and so about the most of their jointes and necke they hang bracelets or chaines of copper, pearle, and such like, as they use to weare,” Smith observed and archaeologists confirm. “Their inwards they stuffe[d] with copper beads and covered with a skin, hatchets and such,” before wrapping the corpses “very carefully in white skins,” and laying them on mats in a temple house with “what remaineth of this kinde of wealth … set at their feet in baskets.”16 In effect, then, because prestige goods died with the chief, weroances and would-be weroances always had to create for themselves anew the tribute networks, the trade connections, the diplomatic and marriage alliances, the masses of prestige goods that undergirded their power. This fact, more than some abstract historical force called “cycling,” undergirded the inherent instability of these chiefdoms as political forms. And it brings us at last to our three travelers, who apparently sought just such connections, alliances, and goods, either as rising chiefs themselves or on behalf of the weroances who sent them.17

* * *

We cannot be absolutely certain that the man usually known by the Spanish name Don Luis or Don Luis de Velasco was originally from Tsenacomoco or even that Tsenacomoco was the same place that he and the Spanish called Ajacán. Yet through careful detective work, scholars Clifford M. Lewis and Albert J. Loomie reasonably concluded decades ago that “there are enough indications available to link Don Luis with the ruling Powhatan clique” and that Ajacán included territories between the James and York Rivers that were later known to be part of the Powhatan paramount chiefdom.18 Spanish sources variously describe Paquiquineo as “a young cacique,” as “a person of note” who “said he was a chief,” as “the Indian son of a petty chief of Florida” who “gave out that he was the son of a great chief,” as a chief’s son “who for an Indian was of fine presence and bearing,” or as “the brother of a principal chief of that region.”19 Unhelpfully, the same sources say that in 1570, he was either “more than twenty years of age” or “a man of fifty years.”20 It is quite possible that, as Lewis and Loomie suggest, Paquiquineo was either the brother or father of Wahunsonacock and his su...