![]()

Chapter 1

Models of Authority

Indians and English maintained a wary distance from each other in the months following the Plymouth colonists’ arrival on the coast of New England in 1620. The newcomers had landed in the bitter cold of November, scouted the area for weeks, and at the end of December had chosen the site of their plantation, set high for defense and with fresh water nearby. English people had been there before, but not as settlers, and members of the Plymouth company knew of Indian violence toward previous visitors to these same shores. Some of those attacks, they also knew, were provoked.1

Throughout the first, cold months of the colony’s existence, William Bradford noted Indians “skulking about them,” but “when any approached near them, they would run away.” Other ominous signs—cries and noises by day and night and “great smokes of fire” in the distance—alarmed the settlers. Frequent sightings and sounds confirmed English suspicions that the Indians were carefully watching them as they built, hunted, and explored the area around their new settlement. But when the English approached the sources of smoke or traveled to places where they had seen Indians far off, they found only empty houses. So it went, through the lean months of November, December, January, February, and early March. Fearing the worst, the English built stockades to defend against Indian attack and kept watch by night.2

The Indians—Wampanoags—had witnessed the power of English guns. So while they observed the English, they remained aloof, trying to judge their purpose and disposition. Previous contacts with European sailors had not inclined them to trust the newcomers. Six years earlier, Englishmen had arrived in ships, seized Indians after pretended overtures of friendship, and taken them away across the ocean, most never to return.3

But some had come back. Epenow, of Martha’s Vineyard, had been to England and returned, bearing tales of English deception and cruelty that may have reached the Wampanoags on the coast. Squanto, who would be one of the first to approach the Plymouth settlers, had also been delivered from English capture. He had returned from captivity to find his village of Patuxet, where English houses were now being raised, empty and his people dead of European diseases brought by the fishermen and traders who had frequented the coast for decades. Bereft of family and friends, Squanto joined Massasoit’s people at Pokanoket.4

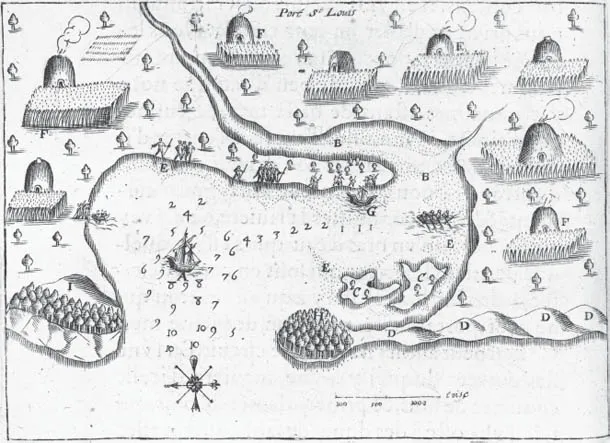

Figure 1. Samuel de Champlain’s drawing of Wampanoag wigwams at Plymouth Bay, July 1605. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

By March the Indians had watched long enough. On the morning of March 16, Samoset, a Wabanaki Indian staying with the Wampanoags, walked “boldly” and “all alone” into Plymouth and, to the amazement of the colonists, addressed them in English and bade them welcome.5

Over the next few days, Samoset remained in Plymouth, and other Indian men came also, bringing furs and indicating through signs their eagerness to trade, a desire the English shared. The winter months had been hard for Plymouth; nearly half the original hundred colonists had died of disease, hunger, and exposure by the end of February.6 It was still too early for harvest of any but the earliest plantings. They needed corn. Too few and weak to defend against any sizeable attack, they welcomed peace.

On March 21, Samoset came to Plymouth yet again, this time with Squanto, who spoke better English. They told the colonists that the leader of the Wampanoags, the great sachem Massasoit, was nearby with his brother Quadequina and they wished to speak with the governor. Within an hour, the sachem appeared at the top of the hill, accompanied by sixty warriors. The sachem’s appearance and bearing both proclaimed his authority. He was tall, like his men, “a very lusty man, in his best years, an able body, grave of countenance, and spare of speech.” Dressed in skins like his followers, he was distinguished by “a great chain of white bone beads” around his neck and a pouch of tobacco hanging behind. After an initial parley between Massasoit and Edward Winslow, sent as the governor’s messenger, the sachem and twenty of his men left their weapons on the ground and followed the English into the village.

Led by Winslow, Massasoit and his men entered a house “then in building” within the town. The English laid down a green rug and some cushions for seating; the sound of a trumpet and drums announced the arrival of the colony’s governor, John Carver, accompanied by musketeers. Carver and the sachem greeted each other, “our governor kissing his hand, the king kissed him.” The governor offered food and drink, which the sachem accepted and shared with his men. Then, as Winslow described it, “they treated of peace.” Each leader promised that he and his people would not harm the other, that they would give warning of danger, that they would assist if the other were attacked, and that they would work to maintain order and peace between the two peoples.

This agreement, made in the earliest days of contact, was the 1621 league of peace between Plymouth Colony and the Wampanoags.7 That agreement established expectations that would have a profound impact on relations between Indians and English throughout the remainder of the century. It would also affect the relationships among the English, Dutch, and French, the several English colonies, and the conflicting groups within each colony, all of whom used the Indian-English relationship as a tool to critique Massachusetts’s exercise of authority and bolster their own. This critique, in turn, would help bring on the intervention of the crown, making the contest of authority span the Atlantic Ocean. Thus the Indian-English relationship is key to understanding the contest of authority in New England, which helped move both Indians and English from independence to dependence by the end of the century.

For the treaty of 1621 to have meaning and therefore power among the Indians and English, it was necessary for the two groups to have similar patterns of authority in their respective societies. There were similarities, but there were also differences that profoundly influenced how each interpreted what precisely was agreed to in 1621. To appreciate fully each party’s understanding of this agreement as well as the larger context of the struggle over authority that lies at the center of this book, we need to know what came before contact.

For up to a century before English settlement, the Wampanoags and other Indians of the northeast had had sporadic contact and trade with Europeans. Trade introduced new materials, language, and ways of doing things into native cultures, but Squanto’s experience demonstrates that European-borne diseases wrought the most dramatic change, killing up to 90 percent of Indians in some areas of New England, including many leaders, undermining the authority of the remaining sachems and religious leaders or powwows, and forcing realignments of Indian groups because of drastically reduced populations.8 Much of this process took place before the first English Pilgrim set foot on Cape Cod.

Yet much of what we know of Indian government in seventeenth-century New England comes from our reading of English accounts that follow the Pilgrims’ landing; they describe the customs and structure of already changed societies that continued to change, adapting to the English presence, seeking to turn it to benefit in their lives.9 People poorly describe the unfamiliar; their natural tendency is to draw parallels with what they know. Early descriptions of Indian societies by English observers apply English labels such as “king” and “prince” to figures who seemed to fill similar roles in an unfamiliar culture. Recognizing the inherent bias of reports filtered through English observers, scholars of Indian North America of the last generation have shifted their emphasis to values and characteristics in various Indian cultures such as government by consensus and egalitarianism that are directly contrary to hierarchical European models.10 Consensus operated when Indians “voted with their feet,” for example, temporarily or permanently shifting allegiance to another community when they were displeased with a sachem’s governance. Rhode Island colonist William Harris claimed that Indians’ allegiance could not be determined by where they were born or resided, but only “by voluntary consent: they are: or are not: Such or such a Sachem’s men.”11

While consent was an important aspect of Indian governance, New England Indians were also much concerned with status and maintaining orderly, ranked societies.12 Well before Europeans arrived in North America, Indian polities in the New England area were organized under sachems, hereditary political leaders acknowledged as superiors by their subjects. While English preconceptions of authority undoubtedly influenced their descriptions of these leaders, Indians themselves witnessed to the hierarchical nature of their societies. One sachem testifying before English magistrates claimed that “he doth know nothing unto what the great Sachems or company of the Indians know for he is a little Sachem and hath few men under him.”13 The very word “under”—“agwa” in the Massachusett language—demonstrates that these relationships were vertical, rather than equal. Indeed, “agwa” is at the root of the words for “subject” and “subjection” in Massachusett. Roger Williams’s 1643 Key into the Language of America included the Narragansett phrases “Ntacquêtunck ewò” and “Kuttáckquêtous,” which Williams translated as “He is my subject” and “I will subject to you.”14

One way that sachems maintained the loyalty of their subjects and demonstrated their power was through generosity, by redistributing goods they received through tribute or by virtue of the trade routes they controlled. Gift-giving, in addition to solidifying a sachem’s power and prestige, helped demonstrate friendships, establish obligations, and renew alliances, playing a vital role in the social life and rituals of Indian societies throughout the northeast.15 Sachems also offered their subjects protection from enemies. In return, subjects had obligations to sachems, such as the payment of tribute. Sachems themselves sometimes paid tribute to higher sachems they recognized as more powerful and from whom they desired protection. Sachems likewise expected payment of tribute from people they had conquered, as the Pequots did from the Montauks of Long Island. Tribute was paid with a number of goods, including deerskins and, increasingly with the arrival of Europeans, wampum—shell beads manufactured by the Indians, which became the chief source of currency for English and Dutch colonists.16

Indians of the northeast signaled the nature of their relationships with each other through the selective use of kinship terms: “fathers” were superiors, “friends” or “brethren” were allies or equals, “children” were inferiors.17 These relationships were not permanent; they could shift from vertical to horizontal and back again. For instance, when the chief sachem of the Narragansetts, who received tribute from the Montauks, desired their support in a war, he raised their status, signaling the change by using terms that suggested a more equal relationship: “and instead of receiving presents, which they used to do in their progress, he gave them gifts, calling them brethren and friends.”18

Map 1. Indians of the Northeast in the early seventeenth century.

Relationships of superiors and inferiors among Indians varied in degree, just as they did among Europeans. For example, William Strachey recorded in 1612 that the Algonquian Chickahominies of Virginia paid “certain duties” to the great sachem Powhatan and agreed to be hired by him as warriors from time to time, but they maintained governmental independence: “they will not admit of any werowance [leader] from him [Powhatan] to govern over them but suffer themselves to be regulated and guided by their priests, with the assistance of their elders.”19 A similar relationship—an unequal alliance—seems to have existed between the Narragansetts and the more powerful Mohawks.20 The Narragansetts sent them presents and sought their aid but governed themselves. The Pocumtucks of the Connecticut River also governed themselves but acknowledged that they needed the consent of the Mohawks, with whom they were “in confederacy,” to take any significant action such as going to war.21

Among the English, both hierarchy and consent were present as well. Their kings, princes, and other royalty are evidence of English hierarchy, an order believed to be of divine institution. But, as among the Indians, hierarchy and consent were frequently—and increasingly—at odds with each other in government. Within a generation of the Pilgrims’ settlement in New England, disagreements over the relative authority of king and Parliament would result in civil war in their home country, leaving England a parliamentary commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell, rather than a monarchy, for over a decade. The opposing imperatives of consent and hierarchy are evident in governments instituted in New England as well.22

The New England minister John Davenport laid out the model for government in an election sermon he preached in 1669: “The orderly ruling of men over men, in general, is from God, in its root, though voluntary in the manner of coalescing and being supposed that men be combined in Family-Society, it is necessary that they be joined in a Civil Society; that union being made, the power of Civil Government, and of making Laws, followeth naturally.”23 God was at the top of the hierarchical ladder implicit in Davenport’s model, and on each descending rung stood leaders committed to acting out his will: king, governor, magistrates, deputies, town officers, fathers, and mothers. Children, women, and servants followed the lead of fathers and husbands in the family order, and the family was the model for civil government, which was “a great family.”24 Like the Indians, the English used family terminology to indicate superior rank: God, the king, and the magistrates, as well as literal parents, were “fathers.” And the fifth commandment requiring children to honor parents was applied to all relationships of authority, between masters and servants, parents and children, rulers and ruled. Under the Puritans’ peculiar interpretation of authority, subjection to these rulers was part of a covenant relationship and thus voluntary.25 But it did not follow that people were at liberty to disobey. They had the right to choose, not the right to govern. Once chosen, leaders, good or bad, must be obeyed.

Plymouth Colony offers a good example of the operation of both hierarchy and consent in English society. The Plymouth Company patent gave the colonists the right to settle the land, but they lacked a charter with authority and guidelines for government. The Mayflower Compact of 1620, a voluntary agreement for government, is evidence of both the colonists’ lack of any regular authority for their enterprise and their acknowledgment that government...