![]()

PART I

The Basics

![]()

Chapter 1

The Ethnic Landscape

Many outsiders think we are one race. But we are not, we are many peoples.

—Afghan Uzbek parliament member Faizullah Zeki, Mazar i Sharif, 2005

Centuries of history contributed to the political and cultural landscape of Afghanistan today. The legend of the Kalash people of Pakistan is a good place to begin to understand that history.

High in the snowcapped Hindu Kush Mountains on the Afghan-Pakistani border lived a Dardic-Vedic people who claimed to be the direct descendants of Alexander the Great’s troops, who had once occupied the land as a distance outpost of empire, only to be erased by succeeding waves of invaders. While the neighboring Pakistanis in the Punjab and Sindh were darker-skinned Muslims, these isolated mountain people had light skin and blue eyes. Although the Pakistanis proper converted to Islam over the centuries, the Kalash people retained their pagan traditions and worshipped their ancient gods in outdoor temples. Most important, they produced wine much like the Greeks in antiquity (although this is no proof of a link to the Greeks)—this, in a Muslim country that forbade alcohol.

In the nineteenth century most of the Kalash—or Kafirs (Infidels) as they were formerly known—were brutally conquered by the “Iron Amir of Afghanistan,” Abdur Rahman. Their ancient temples and wooden idols were destroyed, their women were forced to burn their folk costumes and wear the burqa or veil, and the entire people were converted at sword-point to Islam. Their land was then renamed Nuristan, the Land of Light. Only a small pocket of this vanishing pagan race survived across the border in three isolated valleys in the mountains of what would become Pakistan in 1947.

I had never visited the pagan Kalash tribe but had always hoped to. After we discussed the Kalash in one of my history classes, a student challenged me to follow the advice I gave my classes, which was to get out and see the world. In June 2010 my colleague Adam and I set out to travel into the Hindu Kush on the Afghan-Pakistani border to see this ancient race for ourselves. But when we arrived at our Pakistani host’s house in Lahore after flying through Abu Dhabi, he cautioned us regarding our goal of visiting the lost descendants of Alexander the Great: “It’s a dangerous two-day journey off-road into the mountains,” Rafay warned us. “But that’s not the most important obstacle you’ll have to overcome. To get to the remote homeland of the Kalash you need to cut through the Swat Valley.”

Rafay then pointed to our intended route on a map, and Adam and I groaned. Our dream was falling apart. We both knew that the Swat Valley was a stronghold of the Pakistani Taliban. In 2007 the Taliban brutally conquered this beautiful valley and forced a puritanical version of Islam on the local people. The Taliban also used it as a springboard for sending suicide bombers through Pakistan.

“But all hope is not lost,” Rafay continued. “The Pakistani army just reconquered most of the valley this winter and have opened the main road through it. If you don’t stray from the road and there is no fighting, you just might be able to pull it off.”

Nervous about the prospect of adding a journey through a war zone to our trip to the Kalash, Adam and I then traveled to the capital, Islamabad. There, after much searching, we found an ethnic Pashtun driver who claimed to have once traveled to the remote homeland of the Kalash. He not only knew the route but had a tough SUV to get us there.

After haggling over the price of the trip, we set out driving across the plains of Pakistan, where the heat soared to 120 degrees. Finally, after traversing the country from the Indian border to the Afghan border, we arrived at the mountains. And what mountains they were. The Hindu Kush are an extension of the Himalayas and soar to twenty-five thousand feet. As we drove into the tree-covered mountains, the temperatures blissfully began to drop. And although we found respite from the heat, everyone grew tense. Saki, our driver, warned us that we were now in Taliban territory. We had entered the Swat Valley.

We did not travel far before we were stopped at the first of many Pakistani army checkpoints we would encounter. When the soldiers manning it discovered that there were two Americans in the truck, they strongly warned us to avoid leaving the road. One of them asked us to sign our names in a registration book and proclaimed that we were the first foreigners to enter the Swat since the Taliban had taken it in 2007.

That night we stayed in Dir, a Swat Valley village that locals claimed had briefly served as a hiding place for Osama bin Laden when he fled Afghanistan during 2001’s Operation Enduring Freedom. Kidding or not, that night we slept fitfully. As a precaution, Adam piled chairs against our inn room’s door to keep out any Taliban or Al Qaeda intruders. In the back of our minds we always had the story of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, who was captured by Al Qaeda in Pakistan and beheaded.

The next day we made it safely out of the Swat Valley after crossing a mountain pass at ten thousand feet and a nearby glacier. We were now in the scenic Chitral Valley. We drove up this valley for several hours before our driver grew excited. Gesturing to the dark mountains on our left along the Afghan border, he said one word with a grin—“Kalash.”

With mounting excitement we left the main “road,” crossed a large river, and began to drive up a mountain trail straight into the mountains. This continued for a couple of hours before the narrow valley opened up and our exhausted driver announced that we had finally arrived in Rumbur, the most isolated of the Kalash valleys. Having made our way from Boston to Abu Dhabi to Lahore to Islamabad to Swat to Chitral, we had finally reached our destination in the high mountains on the Afghan border. It was now time to meet the Kalash.

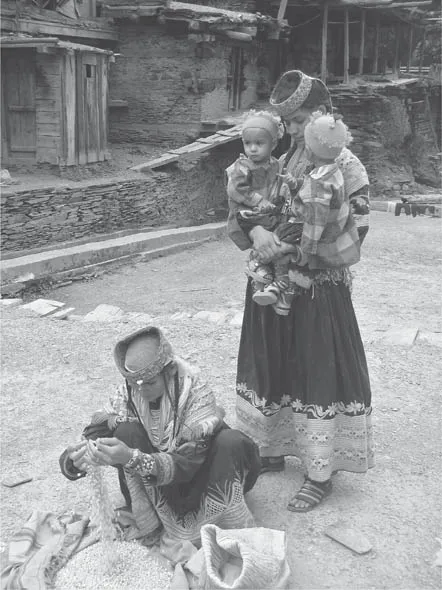

It did not take us long to find them. Adam was the first one to spot a Kalash shepherdess in the trees wearing a stunningly bright peasant costume. After seeing the faceless burqas of the women of the Swat, the juxtaposition between Muslim women and this Kalash woman could not have been greater. As we drove along we saw several more brightly clad Kalash women. But when we tried to take their pictures they ran off and hid behind trees. Worried that we might break some local taboo on photography, we continued on our way.

Soon we entered the Kalash village of Rumbur. The wooden houses were built in steps above one another up the valley’s walls, and the village square filled with Kalash curious to see us. Among them was Kazi, the village holy man. Everyone stood back as he approached us and heard our request to stay with the Kalash for a few days to learn about their culture. Kazi heard us out and thought about it for a while. After some thought, he finally smiled and gave us his blessing. He proclaimed that as blue-eyed “pagans” (the Kalash believe Christians worship three gods, that is, the Trinity) we were like the Kalash and welcome to stay with them.

With that, everyone’s shyness was forgotten and the village men and women proudly posed for photographs and allowed us into their homes. Once again the contrast to the Muslims in Swat and greater Pakistan was startling. The conservative Muslims of Swat had women’s quarters in their houses where no outsiders were allowed. The Kalash women were free and dressed in beautiful costumes that seemed to belong to a different era.

Members of the Kalash in traditional dress.

During our stay we hiked up into the mountains overlooking the Afghan border and were taken to the Kalash people’s outdoor temples. There they made sacrifices of goats to their mountain gods. Sadly, most of their ancient wooden idols had been stolen or defaced by neighboring Muslim iconoclasts who considered them heathen abominations. We were also told that one of the local leaders who fought in the courts to protect the Kalash from such problems had recently been assassinated. On many levels we sympathized with the Kalash—who were losing numbers to conversion to Islam—as a race facing an existential threat. And I must say that after the heat, pollution, and crowds of Pakistan proper, we found this pristine mountain enclave filled with incredibly hospitable farmers and shepherds to be a veritable Shangri-la. Time and again we were invited by smiling Kalash into their simple wooden houses for meals where we talked about life beyond their remote valley. Most Kalash had only left their valley a few times in their lives, usually to go to a neighboring Kalash valley for a marriage or to celebrate a great festival.

On our final evening in Rumbur, the villagers held a feast for us. We celebrated with the famous Kalash red wine. My most endearing memory of the mystical night was of Adam doing a snake dance with a local elder, snapping his fingers in rhythm and dancing lower and lower to the ground in the center of the clapping audience.

The next morning we were awoken by the sound of cows being led by children through the misty village. We said our good-byes to everyone and drove out of Rumbur. As I looked back I saw several Kalash girls standing on a terraced hill above us in their bright costumes, waving to us. With our driver recovering from the previous night’s festivities, we took leave of our hosts. It was now time to reenter Pakistan proper, a land that seemed far removed in space and time from the ancient rhythms of the Kalash villages.

As our journey to the vanishing Kalash people of the Afghan-Pakistani border revealed, the region is home to many different ethnic groups. One of the most difficult concepts for outsiders to grasp is the variation between the groups that make up Afghanistan’s ethnic mosaic. And no subject is more complex than that of the competing allegiances of Afghanistan’s people to clan, village, valley, tribe, or ethnic group. Depending on the situation, all of the above groups can be defined by the Afghan word qawm (pronounced “kawum”), which is usually translated in a rather simplistic fashion to mean “tribe” or “ethnic group.”

There is also the question of the various Afghan tribes’ identification with an overarching sense of Afghan citizenship. Depending on the context, Afghans will identify themselves by their clan, ethnic group, or national identity. There is no better testament to the importance of understanding this thorny issue than the battered remains of Kabul, which was until recently a blasted ruin. Its destruction was caused not by Soviet aerial bombardments but by intraethnic fighting in the 1990s Afghan civil war. The destruction of Kabul is vivid testimony to the importance of ethnicity in Afghanistan today. Although ethnic issues have been tempered since 2001, an understanding of the various ethnic groups can empower outsiders operating in this alien environment. Military leaders have long understood that knowledge of the adversary is critical to operational success. Cultural awareness is an increasingly important component of this knowledge. Indeed, the more unconventional the adversary, the more important it is for the U.S. military to understand the adversary’s society and underlying ethnic-cultural dynamics as a means of waging counterinsurgency.

The Pashtuns: Afghanistan’s Dominant Ethnic Group

Perhaps the biggest mistake Americans make in dealing with Afghanistan is in referring to the Afghans (or even worse, the “Afghanis,” a term that actually denotes Afghanistan’s currency) as a unified or homogeneous people like the Japanese. Afghanistan is more like Switzerland, a multiethnic European country that is home to Germans, French, Italians, and Romansh (there is no “Swiss” language, of course).

But a comparison to the British may be more apt. Historically, multiethnic Afghanistan was formed in much the same way as Great Britain, through the conquest and subjugation of neighboring peoples. At one time or another in their history, the English, Britain’s ruling race, ruled over the French in Normandy, the Celtic-speaking Scottish Highlanders, the Celtic-speaking Welsh, and the Gaelic-speaking Irish Catholics. This does not mean that the French, Scots, Welsh, or Irish Catholics were, or are, English. And one must never make the mistake of calling a Welshman, a Scot, or an Irishman “English” even though he might have a British passport.

Similarly, Afghanistan’s ruling race, the Afghans or Pashtuns (often called Pathans in Pakistan), expanded from their core lands and conquered a kingdom they named for themselves. But this does not make everyone whose lands were forcefully included in the Afghan Kingdom an Afghan in the strictest sense of the term, even though he or she might carry an Afghan passport. However, it should be stated that there is a vague, supraethnic sense of being an Afghan citizen that is perhaps comparable to the British identity of Northern Irish, Scots, and Welsh who are not actually English.

Afghan citizens of Uzbek (Turkic-Mongol), Tajik (Persian-Iranian), and Hazara (Shiite Mongol) extract all share common Afghan cuisine, irrigation techniques, basic clothing, housing structures, fighting tactics, patriarchal traditions, and language of interethnic communication (Farsi-Dari), not to mention an identification with Afghanistan as their broader national homeland. But many non-Pashtun ethnic minorities have a chip on their shoulder stemming from their original conquest by the Afghan-Pashtuns in the nineteenth century. To understand their sense of victimhood, one must understand their conquerors, the Pashtuns.

The origins of the Afghans or Pashtuns are murky and lost in the mist of time. They are, however, seen as being descendants of the Indo-Iranians, an ancient people who are also known as the Aryans. The Aryans settled in Iran (which is a cognate of the word Aryan) and subsequently moved in a southeasterly direction through Afghanistan into India sometime between 2000 and 1000 B.C. Although many people think of Aryans as being Germans, the wave of Aryans that settled in what would one day become Afghanistan and Iran were no less Aryan in their Western complexions. For this reason it should be no surprise that Indo-Iranian is also a member of the same linguistic group as Indo-European, a family of languages that includes Greek, Latin, Slavic, and Germanic languages such as Anglo-Saxon English. Incidentally, the Aryans who passed southward to India established a caste system there based on their lighter skin that allowed them to discriminate against the darker peoples of the south.

The Afghan-Pashtuns are proud of their Aryan heritage and named their national airline Ariana; they have had symbols, such as the wheat with which the mythical Aryan king Yama was crowned, emblazoned on their national flag. Although Afghans are often black-haired or dark-skinned, their features are frequently European-looking and many have light blue or green eyes. The Afghan girl with haunting green eyes on the famous 1984 cover of National Geographic was, for example, an Afghan-Pashtun.

The “real” Afghans, or the Pashtuns, are a disunited conglomeration of peoples made up of two large tribal confederations (the Ghilzais and Durranis), which are broken down into sixty major tribes and more than four hundred sub-clans. Among the most important of the Pashtun sub-tribes are the Wazirs, Afridis, Mahsuds, Mohmands, Shinwaris, and Yusufzais, many of which straddle the artificial border that cuts through the heart of their tribal lands known as the Durrand Line (that is, the post-1893 “frontier” between Pakistan and Afghanistan that was actually imposed on the Afghans by their nineteenth-century British colonial rulers).

The Pashtuns, who make up 40 percent of Afghanistan and 15 percent of Pakistan, speak an Indo-European (Aryan) language known as Pastho that is distantly related to Persian-Tajik, although it is not mutually understood. There are two major Pashtun dialects: that of Peshawar, Pakistan, in the northeast and Kandahar in the southwest.

The Pashtuns are perhaps the world’s largest tribal group, and they have tended to reject state dominance (even by a Pashtun state). For this reason they are defined more by their shared culture, language, and traditions than by a modern sense of nationality. Among the Pashtuns’ most famous traditions is their ancient code of Pashtunwali, which serves them well in lieu of a central state authority. In his book Afghanistan (1973), Louis Dupree describes Pashtunwali as “a stringent code, a tough code for tough men who of necessity live tough lives. Honor and hospitality, hostility and ambush are pared in the Afghan mind.” Many aspects of Pashtun society are shaped by this code, which is a mixture of Islamic law and local traditions.

The Pashtunwali code is not seen by Pashtuns as a defining text like the Declaration of Independence or the Bushido Code of the Samurais. Rather, it is a vague set of cultural values that are instilled in children from birth. Simplistic efforts to capture the real nature of this complex societal code often end up glamorizing the Pashtuns as a heroic race of primeval clan warriors. Other accounts depict the...