![]()

Gardeners Abroad

![]()

From Garden House to Bungalow,

Nabobs to Heaven-Born

S

URVEYING HIS newly won domains in northern India, Zahirrudin Muhammad Babur was appalled. Descendant of Tamurlane and, more distantly, of Genghis Khan, the victor of Panipat (1526) would have preferred to rule Samarkand; instead he had to settle for the dusty vastnesses of Hindustan. In the few years left to him Babur set about putting the stamp of civilization on the Gangetic plain, creating not palaces and forts and cities but gardens, introducing “marvelously regular and geometric gardens” in “unpleasant and inharmonious India.”1 The Mughal ruler was neither the first nor the last invader to look upon the Indian landscape and find it wanting, and neither the first nor the last to remake it in an image more suited to his own notions of an ordered universe. Just as Mughal gardens were a microcosm of the world as it should be, so British gardens became maps of an ideal world seen through their insular prism.

Babur freely acknowledged that what had lured him to Hindustan was its wealth: it had “lots of gold and money.”2 The same magnet drew the British to India. They came originally not as conquerors but as traders, vying with many other nations for a share of the subcontinent’s riches. In 1600 Queen Elizabeth I, a contemporary of Babur’s grandson Akbar the Great, chartered the earliest merchant ventures that would evolve into the British East India Company.3 Their immediate object was to challenge the Portuguese and Dutch in the East Indies and gain a foothold in the lucrative spice trade; India was an unanticipated by-product. William Hawkins, scion of the preeminent Tudor seafaring family, was the first commander of an English vessel to set foot in India, landing at Surat on the northwest coast in 1608. From its modest “factory” or trading station, the Company sent a series of embassies to the court of the “Great Mogul” in hopes of obtaining a firman (royal license) that would smooth the path of commerce. Hawkins himself found such favor with Emperor Jahangir that he was presented with “a white mayden out of the palace.” Mutual gift-giving was a time-honored lubricant of social, political, and economic relations, and one embassy presented the emperor with paintings, “especially such as discover Venus’ and Cupid’s actes.” In fact European arts, both secular and religious, came to exert a fascination for Mughal rulers and artists.4

From Surat British merchants fanned out down the west (Malabar) and up the east (Coromandel) coasts of India, competing with the Portuguese, French, Dutch, and other nationalities. The Portuguese had long dominated the commerce of the Arabian Sea from their outpost in Goa. On the Coromandel Coast, British Madras had to compete with the French Pondicherry, while Calcutta, the latecomer, gradually extended its sway over Bengal, eliminating both European and Indian rivals. Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta became autonomous East India Company “presidencies,” each with its fort and godowns (storehouses) and its expanding staff of merchants and “writers” (clerks or junior merchants), as well as garrisons of soldiers. From the beginning the British, like all foreigners, depended on Indian intermediaries and bankers to facilitate trade, especially in the handwoven textiles that formed the bulk of exports before the Industrial Revolution in England reversed the flow. And like all foreigners they relied on good relations with local rulers—or, if not good relations, at least relations of reciprocal self-interest. This became more complex after the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 and the gradual dismemberment of the Mughal Empire, forcing them to deal with a multiplicity of successor states.

Initially “visions of conquest and dominion . . . seem never to have entered into their minds”—they were hardly necessary—but by the mid-eighteenth century the Company found itself caught up more and more in military confrontations with Indian rulers and with other European powers, often in shifting alliances.5 At the same time, European mercenaries played an ever-expanding role in Indian armies, their services offered to the highest bidder. Company officials often made policy on the spot, especially in the matter of military adventures, counting on the snail’s pace of communication with the directors in London to delay interference until it was too late. Often, too, the three presidencies acted at cross-purposes and were torn by internal dissensions, as indeed were their counterparts in London. Even the formidable Warren Hastings, invested as the first governor-general in Calcutta, found it impossible to control his own council, much less the distant communities of Bombay and Madras and his still more distant employers in Leadenhall Street. Hastings willingly relied on military force to uphold British commercial interests, although he opposed the extension of direct rule in India. Bengal, “this wonderful country which fortune has thrown into Britain’s lap while she was asleep,” had been ceded to the Company under Robert Clive in 1765, but Hastings’s ideal model was derived from the Mughals: an India administered indirectly by Indians in accordance with Indian custom and law, as long as local authorities acknowledged the supremacy of the British governor and council in Calcutta and their right to a portion of landed revenues. Not surprisingly, Calcutta’s first newspaper nicknamed him “The Great Moghul.”6

Within a decade and a half of Hastings’s departure from India, however, a sea change had taken place. In 1799 the fourth and last of the wars with Haidar Ali and his son Tipu Sultan and their French allies ended in the total defeat of Tipu, the “Tiger of Mysore,” at Srirangapatnam.7 The victorious general was Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington. The campaign marked the final transformation from commercial to imperial ambition; empire had duly followed trade. By the time the Company was dissolved in the aftermath of the Uprising of 1857, it had become the shadow master of all India, but its powers had long since been usurped by the British government. It had been “restrained and reformed” by a series of parliamentary acts until it was no longer an independent mercantile entity but a responsible administrative service. The motley collection of “rumbustious and individualistic” traders had metamorphosed into a high-minded team of district collectors, part administrator, part magistrate, part tax collector, and part development officer, “destined to join those many-armed gods in the Hindu pantheon and to become a feature of the Indian landscape.” How appropriate that their compatriots referred to them, not always approvingly, as “the heaven-born.” Over time they came to form something close to a hereditary caste, as a cluster of fifty to sixty interconnected families supplied the vast majority of the civil servants who governed India for several generations leading up to independence in 1947. The empire, it has been suggested, provided a sort of outdoor relief for the British middle class.8 Ironically, in the new order of things, the once-glorious merchants (boxwallahs) and planters ranked virtually on a par with untouchables.

British India was a curious patchwork, even an accretion. An official during its heyday likened the imperial presence to “one of those large coral islands in the Pacific built up by millions of tiny insects, age after age.” Roughly a third of the territory continued to be governed by hereditary princes who exercised considerable autonomy, albeit under the surveillance of representatives of the Indian Political Service. The rest of India was administered directly through the secretary of state in London, responsible to Parliament (when it deigned to take an interest) and the viceroy in Calcutta. Under the viceroy were the governors or lieutenant governors of the individual provinces. While their numbers increased dramatically during the century, the ranks of British civil servants responsible for local administration were ludicrously thin. A thirtysomething “collector” might find himself in charge of a population as numerous as that of Elizabethan England, having as his Burghley a magistrate of twenty-eight and his Walsingham a lad who took his degree at Christ Church scarcely fifteen months past.9 As late as 1921 some 22,000 civilians governed a population of nearly 306 million. Behind them stood a force of about 60,000 British and 150,000 Indian troops. Because both civilian and military expenses had to come entirely out of Indian revenues, poorly paid Indians or mixed-race Eurasians staffed the lower levels of government—police, clerks, and railway workers. Only very slowly did the elite Indian Civil Service admit Indians into its ranks.10

How They Lived Then:

From Garden House to Bungalow

During the early centuries the Anglo-Indians, as the British came to be known (only later did this term come to designate people of mixed race), had two intertwined goals: to live long enough to bring home a sizeable nest egg, preferably enough to set themselves up as landed gentry, possibly even to buy a seat in Parliament. It was an age

What could be more tempting for ambitious young men without family fortune than to “shake the pagoda tree” (pagodas were a form of currency) for all it was worth?

And being young men—some as young as sixteen—they no doubt imagined they were immortal. Yet death was omnipresent. In Kipling’s words, “Death in my hands, but Gold!”12

It has been estimated that about two million Europeans, most of them British, were buried in the subcontinent in the three hundred years before independence. As the proverbial wisdom had it, “Two monsoons are the Age of a Man.”13 Of the nineteen youths who sailed out to India with James Forbes in 1766, seventeen soon died, an eighteenth a little later; only Forbes survived to return home seventeen years after he first landed and to live to a ripe old age.14 It became a commonplace that one’s dinner companion one day might be laid to rest in the churchyard the next—and an often overcrowded churchyard at that, exhibiting “the most frightful features of a charnel-house.”15 As late as 1827 a writer commented, “There is no country in the world where the demise of one of a small circle is regarded with so much apathy as in India. Sickness, death, and sepulture follow upon each other’s heels, not infrequently within the four-and-twenty hours.”16 For Emily Eden, sister of a governor-general, there was no such apathy in her reflection that “almost all the people we have known at all intimately have in two years died off. . . . None of them turned fifty.” In 1880, by which time a network of railroads crisscrossed the country, the viceroy’s chaplain was unnerved to learn that there were coffins stocked in every station along the line as a necessary precaution. Even those who are well, remarked Eden, “look about as fresh as an English corpse.”17 Added to this was the isolation of life in India. The journey from England could take six months or more before the advent of steamships in the mid-nineteenth century and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Communication was achingly slow and unpredictable. Ships were not infrequently lost at sea, with precious cargoes and, for some, even more precious letters, newspapers, and books. “It is really melancholy to think what a time passes between the arrival of each fleet,” lamented Lady Henrietta Clive in 1800; one lived with “constant expectation of news and as continual a disappointment.”18

In the beginning, factors—merchants—were largely confined to Company forts and factories. Here they labored over their account books and dealt as best they could with the steady bombardment of directives from London, usually long out of date by the time they reached India. Not for nothing were the junior factors known as “writers,” living “by the ledger and ruled with the quill.”19 As merchants felt more confident, they moved outside the forts, but security was still a concern. A Venetian merchant made several visits to Surat in the mid-seventeenth century when it was still a hub of trade, its port full of ships from Europe, Persia, Arabia, Batavia, Manila, and China. “Upon the sea-shore, on the other side of the river,” he writes, “the Europeans have their gardens, to which they can retire should at any time the Mahomedans attempt to attack them. For there, with the assistance of the ships, they would be able to defend themselves.”20 What the gardens looked like we are not told, but they may well have been inspired by those of their Mughal hosts—and sometime enemies—enclosed in walls, with fountains and scented trees and flowers.

Unlike Surat—the principal port of the Mughals—Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta were entirely European creations. Madras was the earliest. Legend had it that its founder, Francis Day, chose the site, a small fishing village, mainly because he was enamored of a lady at the nearby Portuguese fort at San Thomé (supposed site of the martyrdom of the Apostle Thomas of the Indies). Certainly it had no obvious advantages: it was little more than a surf-pounded strand on the Bay of Bengal with no natural harbor or even a navigable river. The irascible Captain Alexander Hamilton pronounced it “the most incommodious place I ever saw,” adding that the sea “rolls impetuously on its shore, more here than in any other place on the coast of Coromandel.”21

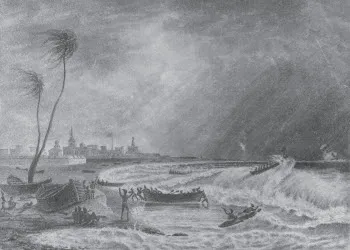

For a first-time visitor, landing could be a harrowing introduction to India. Ships had to anchor beyond the bar, unloading their passengers and freight into small native craft (Fig. 4). Passengers climbed down a ladder, jumped into small native boats bobbing in the heavy surf, and were paddled ashore by nearly naked but extraordinarily agile seamen, clad only in a “turban and a half-handkerchief,” according to Maria Graham, who had married an English naval officer on the voyage out in 1808. Fortunately, their dark skins prevented them from looking “so very uncomfortable as Europeans would in the same minus state,” as one English lady reassured her readers. The sea could be terrifying—“I don’t know why we were not all swamped, as I never saw such frightful waves; and no ordinary boat could have lived in them. I suppose the lightness of the native boats, which are made of bark, sewn together with thick twine, renders them safe. Arrived at the pier a tub was let down, and we were hoisted up in it.”22 This was written in 1867, but little had changed from two centuries earlier except that the boatmen had become Christian and cried out to Santa Maria and Xavier as they battled the surf.

Fig. 4. Surf boats, Fort St. George, Madras. Pencil on paper

[The British Library Board, WD1349] From its founding, Madras was divided into “White Town,” the area centered on its “sandcastle fortress,” Fort St. George, and “Black Town” along the shore to the north. The three-story governor’s house looked out over the Bay of Bengal, with St. Mary’s rising within the fort, the first Anglican church east of Suez. Textiles were the making of Madras, and as the trade prospered whole villages of spinners, weavers, dyers, and finishers transplanted themselves from the South Indian countryside to the growing town. They were joined by other artisans, farmers, and a large population of untouchables who did the menial labor; f...