![]()

1

“BUILDINGS OUT OF HIS HEAD”

In the spring of 1873 Louis Sullivan abandoned his boyhood home near Boston to survey his prospects in the emerging architectural profession in the eastern United States. He had just completed a year in the recently formed architectural program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, led by William Ware, where he was profoundly disappointed by the methods and the goals of the course of study. Instead of encouraging its students to respond directly to the new conditions and opportunities of the burgeoning industrial age, the Boston version of the Beaux Arts system, like its French model, looked to historical precedents as the basis for contemporary design. Like most sixteen-year-olds, Sullivan was prone to action rather than reflection so he quit his studies and traveled to New York to visit the East Twenty-First Street office of Ware’s former teacher, Richard Morris Hunt. Perhaps the source would be purer and stronger than the diluted Boston version. While there, he was shown around by Sidney Stratton (1845–1921), a young architect in Hunt’s office. Stratton must have recognized in Sullivan a pilgrim in hot pursuit of a vision that was as yet unformed—or a hot-headed young man who would be trouble in Hunt’s already stratified office (Figure 4). Instead, Stratton sent him on to Philadelphia to seek training and work with a former member of the Hunt atelier and office, Frank Furness.1

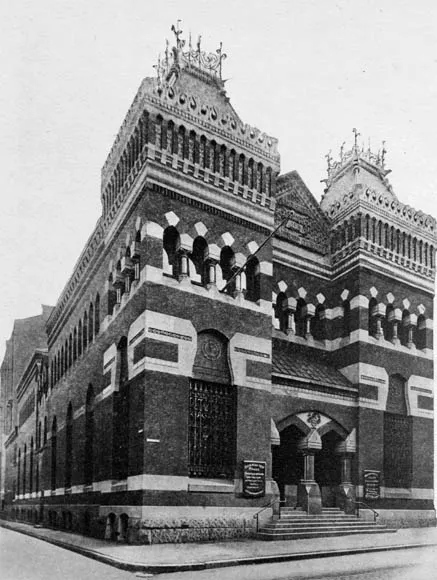

With relatives already living in Philadelphia who could provide housing, Sullivan headed south. But gods don’t take orders. Sullivan recounted that when he arrived in Philadelphia, he decided that, rather than pleading his case directly with Furness, he would look around the city to see for himself if there was any work that warranted his interest. He soon found a remarkable house on South Broad Street that was nearing completion and learned that it was the work of Furness & Hewitt, the very firm that he had been directed to visit. To be sure, after Sullivan had seen Hunt’s recent New York work, Furness’s Hunt-inspired Neo-Grec detail and inscribed ornament would have been obvious in the sea of red brick early Victorian houses of Civil War–era Philadelphia. But an important part of the traditional narrative of the young pilgrim on his quest is the setting of challenges and the overcoming of hurdles. Sullivan’s challenge was to find a master whose vision allied with his own ideas. When he climbed the stairs to the Furness & Hewitt office on the top floor of a modest building at Third and Chestnut Streets, he found a beehive of activity with a small workforce employed on multiple projects that ranged from city and country houses and churches to banks in the financial district and new quarters for some of the largest institutions of the city, including the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.2 Philadelphia’s post–Civil War boom was continuing and the young architects were working at breakneck speed.

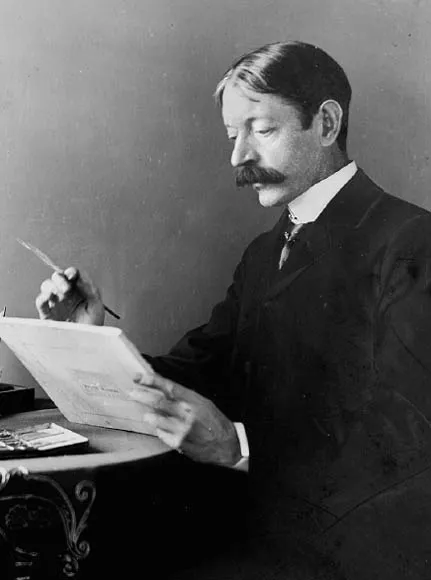

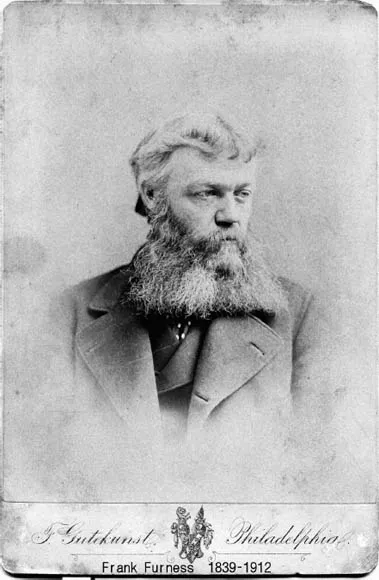

Half a century later, as he recalled his first meeting with Frank Furness and his ensuing time in the Philadelphia office, Sullivan sketched the principals with the deft precision of a novelist.3 George Hewitt was “a slender, moustached person, pale and reserved who seldom relaxed from pose” (Figure 5) while Furness was the opposite, “a curious character” who “wore loud plaids, and a scowl and from his face depended fan-like a marvelous red beard, beautiful in tone with each separate hair delicately crinkled from beginning to end” (Figure 6). Sullivan’s description set up the dichotomy between the two men with their visually expressed identities that paralleled their opposing approaches to architecture. Hewitt had his nose in books, valuing all things English. It was he who did the “Victorian Gothic in its pantalets, when a church building or something was on the boards.” The brash and bold Furness, on the other hand, “ ‘made buildings out of his head.’ That suited Louis better.” As a corollary to his own original mode of work that he had practiced for nearly half a century, he remembered Furness as a remarkable freehand draftsman who “had Sullivan hypnotized, especially when he drew and swore at the same time.” When he left the Furness office late in the fall of 1873, in the depths of the financial crash brought on by Jay Cooke’s railroad speculations, Sullivan had learned a new method of design and received inspiration that would guide him for the next half century in his ground-breaking Chicago and mid-American buildings.

Figure 4 Louis Sullivan, 1876. Ryerson and Burnham Archives, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, Art Institute of Chicago.

Figure 5 George Wattson Hewitt, c. 1880. Private collection.

Figure 6 Frank Furness, c. 1873. Courtesy of the Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.

Sullivan’s story checks out to a remarkable degree, attesting to his own powers of observation as well as the indelible impact of his encounter with Furness. His recollection of the house on South Broad Street led later historians to rediscover the Bloomfield Moore mansion. His characterizations of the office and its location in Philadelphia’s old business district were exact. More telling was Sullivan’s partition of the office into Hewitt’s zone of influence with its historical, English-based sources, each element grasped delicately with “pincers” and placed on a drawing as one might pin a butterfly in a collection, and the contrasting free manner and innovative work of his mentor, Frank Furness. In the scheme of Sullivan’s Autobiography of an Idea, the detailed description of the Furness office and the opposing principals served as a foil to his own career. Hewitt’s historical sources and European models led to the “decorous sublimities of inanity” that inexorably pulled the profession toward the historicism of the Chicago Fair, which undermined Sullivan’s course toward a free American architecture.4 Against the Beaux Arts system of historical models, Sullivan posed his own process of working from analysis of a problem to a direct solution—the method he had first learned from Furness.

Sullivan’s Autobiography framed critical questions that had been debated by architects in the half century between his entry into his chosen profession in the 1870s and his death in 1924 and that continue to be relevant today. Would architects look forward, exploring and utilizing the new technologies and materials created by modern science and incorporating the ever-evolving systems of the modern world into an original architecture worthy of their time? Would they be freed by a new culture rooted in science and rationalism to shape new types of spaces and new forms that both fitted and gave aesthetic expression to modern life? And would they be empowered by a new type of client, one with the new knowledge of the age who could become a collaborator on a design, providing ideas as well as money and a site? Or would they continue to rely on historical models that forced contemporary life into the straitjacket of the past? Sullivan’s texts and buildings and the texts and designs of his pupil Frank Lloyd Wright both looked forward and as a consequence have been incorporated by later historians as key progressive American contributions to modern architecture. Frank Furness, apart from his bit role as the critical catalyst in the Sullivan narrative, disappeared.

Because Sullivan’s Autobiography remains an essential part of the literary canon of American architecture, his praise for Furness has never been forgotten, though later historians such as Henry Russell Hitchcock scoffed at it.5 After all, to paraphrase Hitchcock, writing in 1936 with the goal of connecting Henry Hobson Richardson to the narrative of modern architecture, how could Sullivan, who mattered to the modernists, have learned anything from the Philadelphia oddball? There were additional roadblocks to understanding Furness and his work. By the 1950s, when Furness was being rediscovered by a new generation of scholars and architects, the outlines of modern architectural history had already been delineated and Furness and, for that matter, post–Civil War Philadelphia, were largely excluded from the story. Formulating their histories to make a connection between American architecture and the reigning European International Style modernism, architectural historians traced a genealogy from the Germans who had trained in Peter Behrens’s shop, Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and the Swiss Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier) back to Chicago and Frank Lloyd Wright, and from Wright to his master Sullivan, finding connections via visual motifs that were more a matter of tangency (a chance similarity) than congruency (an invariant and internal consistency). But in the United States, the historical narrative diverged, in part because of earlier Sullivan essays, first published in 1901 and 1902, and collected in book form in 1918 as Kindergarten Chats. There, in an early essay entitled “An Oasis,” Sullivan had praised what he had learned not from Furness but from his contemporary Henry Hobson Richardson (1839–1886) of Boston, whose Marshall Field Wholesale Store in Chicago was personified in a piling up of words nearly as massive as the building: “Here is a man for you to look at. A man that walks on two legs instead of four, has active muscles, lungs and other viscera; a man that lives and breathes, that has red blood; a real man; a virile force—broad, vigorous and with a whelm of energy. . . . Four-square and brown, it stands, in physical fact, a monument to trade, to the organized commercial spirit, to the power and progress of our age, to the strength and resonance of individuality and the force of character.”6

Sullivan’s image was compelling, though it was at odds both with the delicacy of much of his own mature work and the actuality of the Richardson building, which was U-shaped in plan, brick red in color, and conventional in construction.7 This is not to say that Richardson’s later works in Chicago, the Glessner house and the Marshall Field Wholesale Store, had no role in Sullivan’s evolution as a designer or for that matter in the large, simplified forms of post–World War II corporate modernism. The monumental, arcuated, giantism and coloristic unity of the Wholesale Store affected all of Chicago architecture and in Sullivan’s case caused him to turn from the small-scale, piecemeal designs such as the Jewelers Building (Figure 7), or his north Chicago townhouses that characterized his earliest Furness-influenced work, toward the greater simplicity demanded by the vastly larger scale of modern high-rise buildings. In its impact on Sullivan’s Auditorium Building and his later masterpieces such as the Wainwright Building in St. Louis and the Guaranty Building in Buffalo, Richardson’s broadly scaled mode was vital, but as Sullivan later realized, the historical allusions and primitive masonry construction were contrary to his own expression of the new means of steel-frame construction and out of place in the new times that formed the setting for his work. Instead, Sullivan’s method, whether for high-rise office buildings or sprawling department stores or his late, brilliantly detailed, small-town banks, focused on finding direct solutions using contemporary technics and self-created detail. Where Richardson relied on historical sources, in a method learned at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and sanctioned by the architectural profession, Sullivan’s approach, learned in Frank Furness’s office, began with the logistics of use and movement expressed in plan and fenestration, to which were added the efficiency and elegance of new construction materials to produce architecture that aimed toward the specifics of a task and a forceful expression of purpose.

Figure 7 Adler & Sullivan, Jewelers Building, Chicago, 1881. Photograph by George E. Thomas, 2008.

Sullivan’s Autobiography was written at the end of the first quarter of the twentieth century, a generation after his profession had turned from Victorian individualism to historicism and Beaux Arts groupthink, leaving Sullivan, like his mentor Furness, outside the mainstream. Ironically, after participating in the creation of the steel-framed, modern office building in the city most identified with its design and with his career in decline, Sullivan was left with a niche market for brilliant jewel-like banks that were scattered in small Midwest towns (Figure 8). Their sites, far from the urban centers, enabled him to conceive original, nonhistoric, billboard-like façades that stood out on the street and demanded attention. In their color, their concentrated and original ornament, their personal intensity, and their brilliantly lighted spaces, they recalled the banks that Furness was designing in 1873 when Sullivan was in his office (Figure 9). Sullivan’s late projects explain the particular focus of his narrative about his time in Furness’s office, which ignored the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Jewish Hospital, focusing instead on projects on which he had worked such as the “Savings Institution that was to be erected on Chestnut Street.”8

Figure 8 Louis Sullivan, Merchants’ National Bank, Grinnell, Iowa, 1914. Photograph by Robert Thall, 1977. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, HABS IOWA, 79-GRIN, 1–1.

Figure 9 Furness & Hewitt, Guarantee Trust & Safe Deposit Company, 1873. Building now demolished. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The Chicagoan’s recall of the exuberant and individualistic banks by Furness and the obvious link between these buildings and his own late works forms yet another bridge between the two men. In any event Furness’s reputation owes a great debt to Sullivan. The Autobiography of an Idea kept the memory of Furness alive even as his early twentieth-century midwestern banks countered the dull repetitiveness of the standard Beaux Arts banks that dotted most towns. Fortunately, Sullivan’s banks w...