![]()

Chapter 1

From China to Japan

The History of Asian Spaces

Garden Stroll I: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

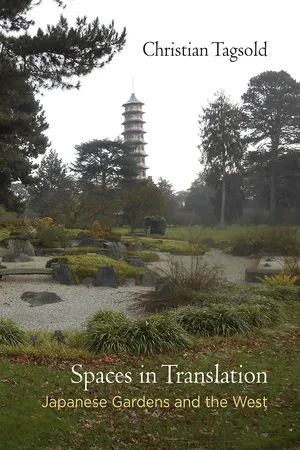

Our first garden stroll takes us through the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, London. The gardens have many attractions, but the most eye-catching is the Pagoda located at the south end of the park, which stands ten stories (fifty meters) high. The layout of the gardens encourages visitors entering through one of the main gates to walk on the grass, taking in the Pagoda Vista, the name of the path leading up to the structure. The view of the Pagoda is very impressive when approached in this way. However, upon closer inspection, the building itself does not look as Chinese as it does from afar. Its octagonal layout and the overhanging roofs of each story certainly have a chinois flavor, but the plain brick walls and red window frames look rather English. That is a bit unsettling, as is the noise. The Pagoda is situated below one of the main approach paths for aircraft using Heathrow Airport, and planes pass overhead every two minutes, disturbing the peaceful atmosphere. Indeed, the Pagoda is one of the West London landmarks visible from these aircrafts.

When the Pagoda was finished in 1762, the land was not yet designated a royal botanic garden. It belonged to Augusta, the widowed Princess of Wales, who had appointed the architect Sir William Chambers to extend the garden of her late husband, Frederick, Prince of Wales. Chambers had been to China and was therefore well suited to bring to Kew the chinois flavor so in vogue during the eighteenth century. Before his death, Frederick had commissioned a House of Confucius in 1749, which Chambers may also have planned. Under Augusta’s patronage, a Chinese pavilion and the Pagoda were erected as well.1 Chambers planned a total of twenty-three buildings for Kew, among them a Moorish alhambra and a Turkish mosque to flank the Pagoda. The Pagoda itself was then much more colorful than it is today, with roofs made of tiles that were varnished green and white, gaudy banisters, and eighty dragons on the roof corners. In line with the fashion of the times, the garden thus offered visitors various curious experiences.

Today the House of Confucius, the alhambra, and the mosque are all gone, as are the dragons of the Pagoda. Instead a Japanese garden is situated near the Pagoda. It is not fenced off as are many Japanese gardens in the West; benches, plants, and pebbles clearly demarcate how visitors should move within the space. Small signs are present, asking visitors not to step on the pebbles. The Chokushi-Mon (Gateway of the Imperial Messenger), built for the Japan-British Exhibition of 1910, now occupies a space on a slight slope in the middle of the landscape. It was given to the Royal Botanic Gardens after the exhibition and was left to deteriorate until it was restored as a centerpiece of the new Japanese Landscape.2

Through the proximity of the Pagoda, the gateway, and the Japanese Landscape, the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew vividly links the various vogues of Asian gardens in the West (see Figure 1). If the Pagoda is the archetypical building of the Chinese vogue of the eighteenth century and its architect, William Chambers, a popular but also controversial designer of the era, the Gateway of the Imperial Messenger is one of the finest examples of Japanese architecture at fairs in the Age of Imperialism. Today gardens like the Japanese Landscape can be found all over the world, with the more recent examples proof of the long-lasting popularity of Japanese gardens.

THIS FIRST STROLL through a garden has taken us into a chinois setting that demonstrates that Japanese gardens were not the first Asian-style gardens to be regarded highly in the West. During the eighteenth century, long before the first Japanese gardens were built in Europe and North America, chinois architecture, Chinese-style garden layouts, and the Pagoda of Kew were in vogue. Just as Japanese gardens would be popular in the context of Japonism roughly a hundred years later, these buildings and gardens were part of a fashion for all things Chinese. Most significant of all Chinese imports was porcelain, the white gold that astonished Western nobility until Europeans found out how to produce it themselves. Besides porcelain, Chinese-inspired interior decorative schemes and ornamental art were popular. But the Chinese fashion had a philosophical side as well; some of the best minds of the century, like Voltaire, felt a certain affinity for Chinese thought.3

Figure 1. In the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, the Japanese Landscape (1996; in the middle) and the Gateway of the Imperial Messenger (1910; to the left) in front of William Kent’s Pagoda (1762; to the right) visually connect three vogues of Asian gardens and buildings in Europe. Photograph by the author.

This Chinese vogue was a consequence of expanded trade relations in the eighteenth century, but of course actual gardens were not direct imports; only the idea of the Chinese garden was taken up and given concrete form. The richest and most powerful rulers in Europe adorned their vast parks with Chinese-style gardens and chinois edifices, but lesser sovereigns, too, wanted to keep up with fashion, even when it was beyond their means. These gardens reached remote places and were soon ubiquitous in Europe. The “Chinese” effect of these gardens was often limited to chinois buildings with an exotic touch such as pagodas, bridges, or teahouses. The design and initially the plants of the gardens rarely had any prominent “Chinese” qualities to offer, though the importation of plants did become more significant later on. However, some of the garden designers emulated Chinese-garden design in the overall layout of their plans and thus achieved a more profound Chinese effect than those who just added chinois buildings to a picturesque garden. The difference between a Chinese effect through chinois buildings on the one hand and the same effect achieved through deeply embedded planning decisions certainly matters for contemporary connoisseurs of garden design as well as for present-day garden historians. Yet contemporary unknowing visitors probably did not see much difference between the two ways of bringing China into European gardens. For them, both turned Western garden scenes into a more or less perfect Chinese scene.

China went out of fashion at the end of the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, some of the basic features of Western interpretations of Chinese-style gardens experienced a rebirth in the nineteenth century in Japonism. Some Western architects in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries even deliberately established a relationship between the first Asian fashion and the new one. In Brussels the architect Alexandre Marcel used chinoiserie motifs in a Chinese pavilion that stands near the Japanese tower at Laeken, which were both built beginning in 1901.4 In truth, some of the recurring motifs that have been ascribed to Japanese gardens in the second Asian vogue have their origins much earlier and point to China instead. This enables useful comparisons between Chinese gardens of the eighteenth century and Japanese gardens of the nineteenth century.

Nature

First and foremost there is a striking similarity in the use of the word “nature,” the employment of which as a descriptor of Chinese design reached its peak with the Jesuit Jean-Denis Attiret in the middle of the eighteenth century. The Jesuit mission to China had been set up in the sixteenth century, and because they had accommodated Chinese ways, the order had gained access to the inner imperial circles of Beijing to a degree no other Europeans had managed.

Accommodation required a certain respect for local customs in order to strengthen mutual confidence, which would in turn ease the process of winning converts to Christianity; for example, Jesuits wore the clothing of the Chinese Confucian scholars even as they tried to convince the imperial bureaucracy of the merits of Christianity.5 Their methods were criticized severely by orders that were less willing to compromise, but accommodation afforded the Jesuits unique insights into Chinese culture. In a sense, the Jesuits were early ethnographers using participant observation and, by the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, had built up a quasi-monopoly on interpreting China to the West. In this setting, Attiret became the court painter for the emperor when he arrived in Beijing. He and other Jesuits regularly sent letters full of information back to Europe, which sometimes were published and circulated as authoritative sources on China by intellectuals. One such letter was written by Attiret in 1743 after he had been in China for a decade. Attiret reported his visit to the imperial gardens of Yuanming Yuan, the Old Summer Palace, which had deeply impressed him.

Others, including some non-Jesuits, had also written about Chinese gardens before Attiret.6 Sir William Temple’s essay “Upon the Gardens of Epicurus,” written in 1685 and published in 1692, was the first European writing to discuss the merits of Chinese gardens in depth. The essay described them as irregular and informal, unlike European gardens.7 Chinese-garden enthusiasts like Anthony Ashley Cooper (third Earl of Shaftsbury), Joseph Addison, and the poet Alexander Pope had also stressed this point early in the eighteenth century.8 But unlike these others, Attiret could offer a firsthand account; his letter was based on his visit to such a garden and not mere hearsay.9 The letter was translated into English a few years later and became even more widely read in Europe. “They go from one of the Valleys to another, not by formal strait Walks, as in Europe; but by various Turnings and Windings, adorn’d on the Sides with little Pavilions and charming Grottos,” he wrote.10

Attiret’s interpretation of Chinese-garden art and his understanding of nature blended well with a general development in English-garden design in the eighteenth century. Baroque gardeners loved symmetries and straight lines. English gardens introduced winding paths instead. The feet could not follow the eye any more in such parks, and Attiret had pointed out that the same principle ruled in China. In 1774, the French Duke d’Harcourt summarized the various garden cultures, declaring that while the French used geometrical planning, the English simply planted their houses in a meadow and the Chinese built horrific waterfalls in front of their windows: “voilà trois genres d’abus.”11 For Attiret, “nature” was the element missing in the garden designs he had left behind in Europe. Attiret frequently used the words “rustic,” “nature,” and “natural” to describe his impressions. But nature was not, in his eyes, completely opposed to art. The appeal to nature did not mean gardeners had to retreat and let nature do the work on her own. Real artists of gardening knew how to copy nature: “The Sides of the Canals, or lesser Streams, are not faced, (as they are with us,) with smooth Stone, and in a strait Line; but look rude and rustic, with different Pieces of Rock, some of which jut out, and others recede inwards; and are placed with so much Art, that you would take it to be the Work of Nature.”12 For Attiret, a “Chinese garden is a site where an excess of artificiality is used to create an illusion of nature.”13 Nevertheless, this implies that nature can be art and vice versa and that an artistic garden is one that copies nature meticulously.

The conquest of Europe by Chinese-style gardens and chinois buildings in gardens emanated outward from England. This garden style was called “anglo-chinois” on the Continent. However, many gardens added a Chinese touch mainly through chinois buildings and not by including Attiret’s interpretation of nature as a conceptual base for their layout. William Chambers was the most popular Western architect to apply ideas from the Far East and add a chinois touch to gardens. He had been to China (although John Dixon Hunt has downgraded the fame derived from his travels as an “exaggerated claim to firsthand knowledge of China”),14 and his writings, with their examples of Chinese design, were used all over Europe as guidelines for attaining Chinese flair. They helped popularize chinois architecture in gardens in France, where the Trianon de Porcelaine had already been built in 1671. In Prussia, King Friedrich II’s Sanssouci, with both a Dragon House and a Chinese House, was influenced by Chambers’s sketches, while in Russia Catherine the G...